Author: Carl Smith

Landscape Architecture Can Better Contribute to Greener Recoveries: 3 Key Strategies

I was born, raised, educated, and practiced landscape architecture in the UK, before moving to the US and a role in design in education 14 years ago. Both of my “home countries” are currently considering future trajectories for resilient economies and greener recoveries, and here I offer some brief reflective remarks and formulate three key strategies for landscape architecture to contribute to the build-back better rhetoric that is emerging on either side of the Atlantic.

In the US, the Green New Deal resolution (GND), published by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey around two years ago, sets forth an economic stimulus and mobilization framework for decarbonization and social equity. While the GND, at present, amounts to little in the way of specifics for its visioning of a decarbonized US economy, across the Atlantic, the UK Government’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution from last November, explicitly touches upon specific areas such as renewable energy planning and special planning designations to protect landscape assets. Anyone familiar with the UK’s landscape profession over the past quarter century, will recognize these sectors as established foci for British landscape practice and instrumental research. The British landscape profession looks well-placed, therefore, to make a significant contribution to the Green Industrial Revolution, though some inherent methodological weaknesses in British landscape planning are worth touching-upon, and I’ll return to this below. Meanwhile, the Landscape Institute – the UK’s professional landscape architecture body – has taken measures to encourage consideration of greenspace in recovery strategies via the recent Greener Recovery: Delivering a Sustainable Recovery from COVID-19 position paper. By way of contrast, the American landscape architectural community’s response to the GND (and climate change through landscape architecture more generally) appears to be one of those instances where the academy – specifically critical theory and speculative design – is starting to drive the conversation for the profession to follow and refine. A supportive statement by the American Society of Landscape Architects mere days after the GND resolution’s publication notwithstanding, the current Green New Deal Superstudio initiative across academic landscape units nationwide is arguably the field’s most visible contribution to date.

The possibilities of having landscape architecture students and scholars from across the USA – and elsewhere – leading the discussion on how to deliver the Green New Deal is very exciting and, perhaps, appropriate. The design studio, after-all, is perhaps less beholden to the usual incremental, top-down nature of practice that might, ultimately, delimit the profession’s contribution to the GND. The resolution’s attempt to ethically reformulate US energy production sets a series of nested systematic challenges that are surely beyond the piecemeal site by site approach of most professional landscape architectural commissions. An exception could be made for practice centered around the ideas of landscape urbanism, whose sensibilities, methods, and techniques focus more clearly on the conceptualization and communication of systematic landscape complexity, and its foregrounding of process over product. However, I think that the sometimes-complex terminology of landscape urbanism could be problematic in the translation of GND-related projects, especially with an eye to the future facilitation of critical public buy-in. To be fair, despite pockets of practice, landscape urbanism has, to a large degree, dwelled in the halls of the academy and has therefore survived with its more verbose corners intact, rather than smoothed over by the rough and tumble of a broader to-and-fro. From that perspective, the application of landscape urbanism to the challenges of the GND – and especially in communicating complex and challenging issues effectively – could therefore lead to a next phase in its maturation, with its more obscure language and graphical approaches being adapted and humanized for broader consumption. In fact, I believe that this speaks to a broader notion that landscape architecture’s ability to translate inherently difficult concepts authentically and evocatively to the public, will dictate its contribution to green recovery plans, just as much as its facility with natural and cultural phenomena. Part of the solution might be to look – again – to the academy and work on ideas of cultural ecology, the democratization of architectural production, and working authentically with communities to weave their narratives of place and memory into design and planning solutions.

Figure 1: Drawing with a community group in Conway, Arkansas to understand local concerns, aspirations and memories relating to a downtown area, slated to become a low impact development park.

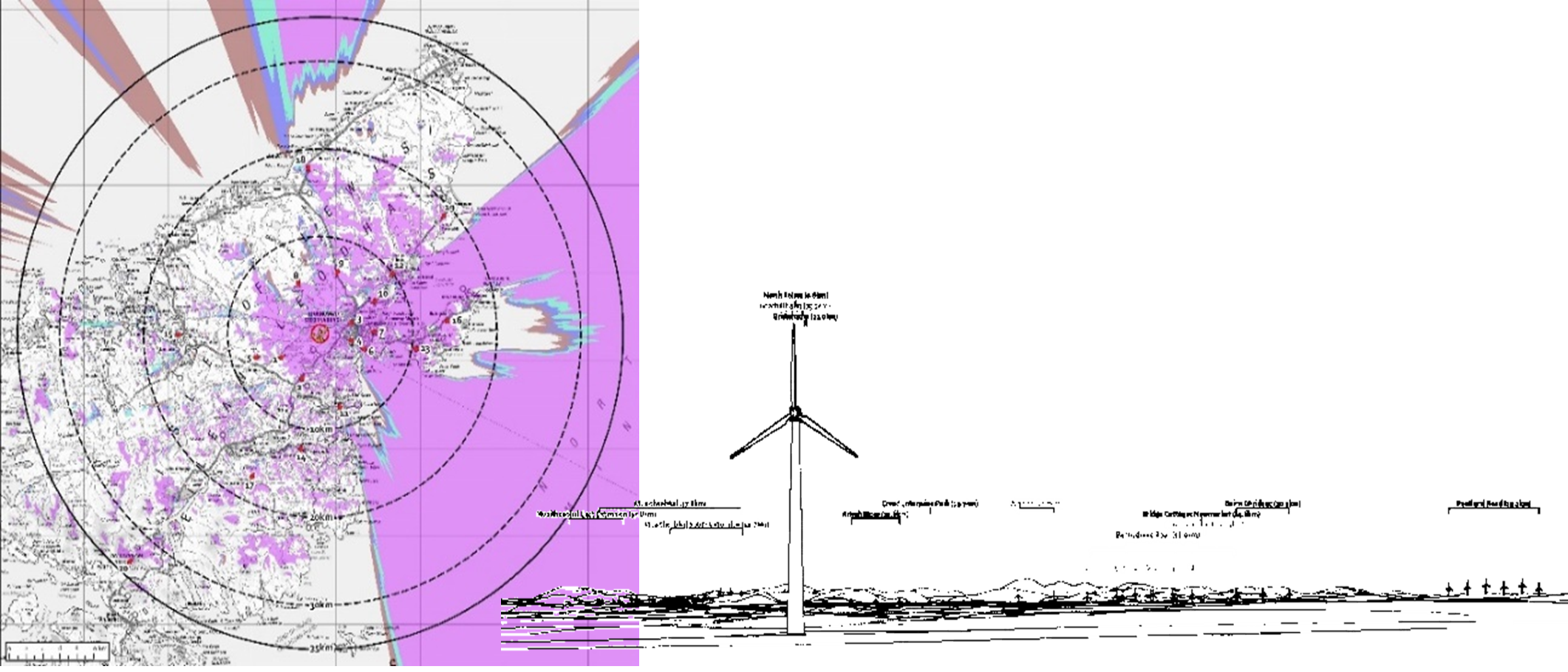

Unfortunately, established landscape practice – in the US and UK both – have fallen into habits, or has been backed-into positions through broader planning and development practices, that cleave to reductive notions of community participation and even sustainability itself. These entrenched behaviors will ill-serve green recovery efforts moving forward. For example, British planning practice has, first and foremost, looked to provide a schedule of effects on spatial landscape qualities, such as quantity, form, extent, and relative position, and on the impacts on visual receptors such as number, location, density and sensitivity of people. The impact on views is generally based on an assumption that the public’s visual preferences and sensibilities are “pro-nature” (itself a canard in the UK setting, considering the deep anthropogenic influence rendered across the British Isles for millennia) and antagonistic towards any technocentric imposition. While public participation and qualitative considerations are encouraged in the planning permission process, it is neither mandatory nor regulated. Meanwhile, British landscape scholarship over the past 15 years, has consistently pointed to nuanced and, sometimes, counter-intuitive public attitudes, associations and aspirations related to large-scale landscape change. The kind of renewable energy infrastructure encouraged by the Green Industrial Revolution, for example, has been found to be a source of community pride and amenity, a tourist destination, and a local badge of regeneration and innovation. This, again, suggests an important future role for landscape architects working closely with communities to understand their sense of place and landscape-narrative, with emerging local stories just as surely taken into account in evaluating development sites and designs as data on geology, ecology, traffic, economics and so-on. And this example again reiterates the need for landscape practice to operate more closely and synergistically with the academy if it is to make a telling contribution to green recovery plans.

Figure 2: Typical approaches used to model, analyze, and communicate landscape change through “sustainable” wind-power development in the UK (Courtesy of Brindley Associates, Edinburgh, UK).

As far as greenspace planning and design is concerned, the pandemic has seen a resurgent global appreciation for the health and aesthetic benefits accrued from public parks and gardens. This is clearly an important opportunity for landscape architecture to stake a role in the post-pandemic recovery and help weave green spaces and infrastructure into the narrative of social equity and decarbonization. However, for this to be played out successfully, the profession – in the UK and the USA alike – needs to push-back on the ideas of greenspaces as site-by-site panaceas for all environmental and social ills. This approach – which can be traced back through 30 years of practice post the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, and latterly facilitated by the emergence of sustainability check-box scoring for individual projects – has led to the debilitating notion that “green design” is a generic type, with its own set of aesthetic modes and signals that rests on a standard suite of tropes of “natural” forms, native vegetation, conspicuous drainage infrastructure and so on. However, this approach may lead to little more than contrived patternmaking or green value-signaling, rather than truly hermeneutic design and planning. Rather than focus on shoe-horning every sustainability tactic into each-and-every site, in the hope that it makes a telling contribution, there is a need to focus on a more strategic understanding of greenspaces as a network rather than discreet sites, where each project has different priorities based on its inherent capacity to foreground certain social and environmental objectives, in service to a broader, complex system.

Figure 3: Greenwich Ecology Park, London. A site of community recreation and brownfield ecological restoration, whose design and program is unique to the park site’s history as both a wetland, and a despoiled industrial landscape; its modern context as a site for exemplar sustainable housing; and its ongoing, skilled management by The Conservation Volunteers.

In closing then, I believe landscape architecture can make a telling contribution to green recovery initiatives such as the Green New Deal in the US, and the Green Industrial Revolution in the UK, provided there is due attention to three key strategies. Firstly, in matters of sustainable greenspace design, individual projects should be guided by a strategic overview of urban fabrics and their embedded spaces, rather than a checkbox approach to site-by-site performance. Secondly, landscape responses across scales need to be enriched by authentic dialogue with local communities, and evaluations of landscape change need to be broadened to consider narratives, stories, and local sense of place. Thirdly, and finally, practice will need to engage more-fully with the academy and creative scholarship to better implement ideas of cultural ecology and democratization; to translate and communicate the systematic ideas of landscape (or ecological) urbanism; and to take inspiration from speculative design studios such as the ongoing Green New Deal Superstudio.