Stories of Disease, Stories of Culture

Pandemics are ancient—as old as human culture itself. Wherever they have struck, they have challenged humans to reevaluate their relations to their environment—as well as the cultural myths that underly these relations. In the face of crisis, these myths—the stories we tell about ourselves—can act as foundations for resilience just as they can constitute sources of vulnerability.

At the “Designing the Green New Deal” conference in Philadelphia in the fall of 2019, the writer and activist Julian Brave NoiseCat spoke of the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—a five-hundred-year-old constitution that has guided its people through settler colonialism, military invasion, pandemics, and the systematic government kidnapping and reeducation of children. “Cultures are really just manuals for how we’re going to do all these things together as people. If the Haudenosaunee can maintain their Great Law against an apocalypse, against genocide, I do believe that culture, and the stories that we tell about ourselves, and the words that we use to tell these stories, are some of the most powerful things that we have.” As we sit in quarantine, it’s worth asking what COVID-19 says about our ways of inhabiting the planet—and how our stories might change in response. We wouldn’t be the first to do so: artists have long used plagues to amplify questions about what it means to be human.

In Albert Camus’s The Plague (1947), an Algerian city is walled off following the outbreak of plague. When the disease abates, the city celebrates, but the protagonist, a doctor, knows that the plague will eventually come back, because “everyone has it inside himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune.” More than a simple disease, the plague is a reminder of the fragility of the human condition.

In Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), a shepherd witnesses the progressive falling apart of human civilization due to plague. Cities, art, and society all disintegrate, leaving the shepherd to roam alone through an emptied landscape. Shelley’s is a pessimistic plague, insisting that humans are not the center of the universe, that pride comes before the fall.

In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842), groups of nobles flee the cities—to a rural villa and a gothic abbey, respectively—to avoid disease and pass the time in celebration. Bocaccio’s youths use their quarantine as an opportunity to inspire and amuse each other with tales of humanity; Poe’s bored aristocrats come to a bloody end among the decadent trappings of their entertainment.

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a group of educated young friends pursues an aristocratic vampire landlord through a complex network of cities, ships, trains, and properties. Stoker’s novel, and especially F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film adaptation Nosferatu, use vampirism and disease to speak of the fear of the Other—especially the Easterner—and of the spread of contagion through an increasingly globalized infrastructure.

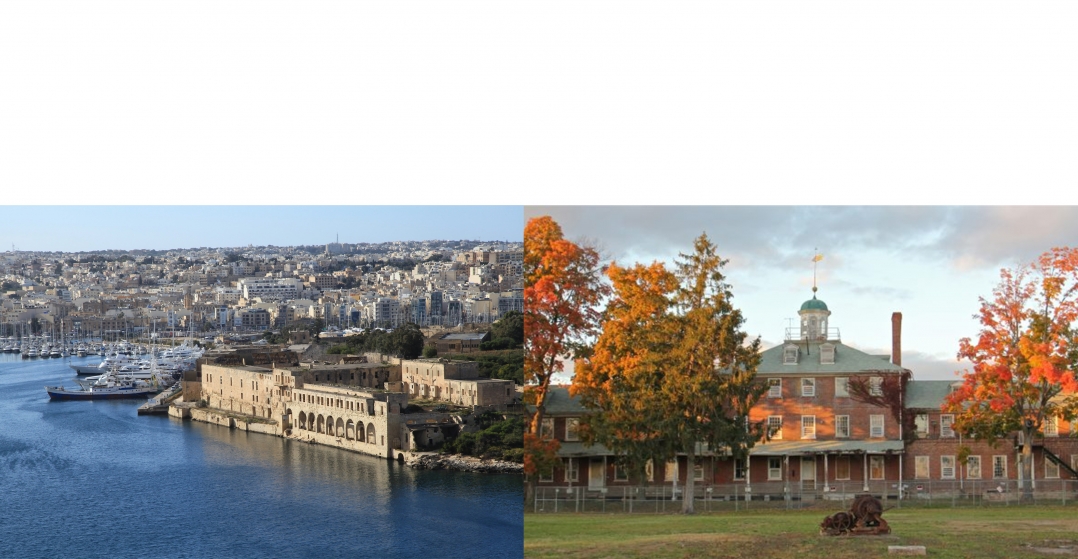

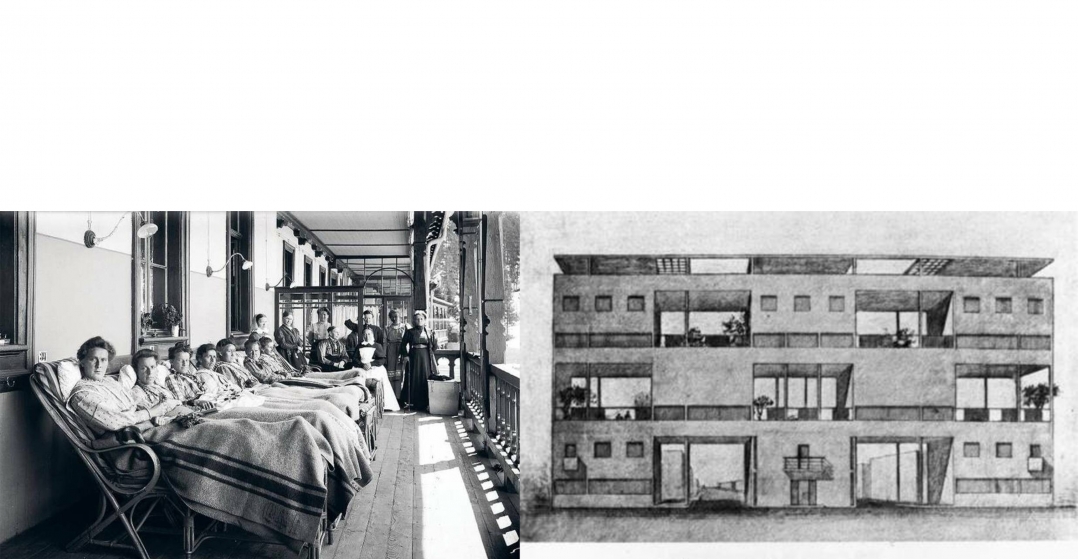

Each of these stories imagines disease through specific spatial contexts. For Camus, walls keep the plague in; for Poe and Bocaccio, they hold it out. Shelley’s shepherd is left to wander the ruins of urban and rural life, whereas Stoker’s young professionals travel through a highly connected urban-rural landscape. These stories of disease are also stories of space, of how its management—through walls, public squares, roads, and countryside—enables life and death.

In 1721, the French painter Michel Serre depicted a scene from the Great Plague of Marseille. Dreary clouds loom over buildings that appear empty and lifeless. The city square, the heart of the public realm, is strewn with bodies, the distinction between living and dead blurred. At the center of this maelstrom, sitting calmly on a rearing horse, a city official directs the removal of corpses, a modicum of order in a portrait of devastation.