Author: Julio C. Verdejo

The Geodesign Framework: Prioritizing Community Voices in the Design of Future Recovery After Hurricane María in San Juan

The impact of Hurricane María, a category-4 storm and one of the strongest hurricanes in Puerto Rico’s history, resulted in a total collapse of power and communications infrastructure. In San Juan, the US territory’s capital and most populated municipality, neighbors, cleaning up, wondered what they would do next. It is during this time when I first visited the Barrio Venezuela sector of Río Piedras. Together with the local churches, organizations, and the community social work team of the University of Puerto Rico’s (UPR) CAUCE Center, we distributed supplies. Walking within the narrow walkways and steps of El Hoyo (or The Hole) is when I decided to concentrate all of my efforts as a planner and a Geodesign graduate student to help the people of Barrio Venezuela.

Barrio Venezuela developed due to the significant landscape changes in Puerto Rico during the 20th century: Deforestation, monoculture, industrialization, migration, suburbanization, and forest regeneration were all present in the space of one century. This period saw the development of extensive informal settlements or shantytowns in the periphery of urban centers.

South of Río Piedras, new migrants built Barrio Venezuela in 1910; it was named for its resemblance to hill neighborhoods in the Venezuelan capital, Caracas. Comprising an area of approximately 40 acres with a population of 880, Barrio Venezuela is an example of the effects of continuous and gradual landscape changes. These changes have become stressors that have left residents significantly limited in their social conditions and interactions. San Juan’s urban expansion meant Barrio Venezuela became trapped in a car-centric bulge urbanization pattern around the Río Piedras city center. This pattern is now a mix of first-generation suburbs built in the 1940s and 1950, highways and institutional land uses represented by the University of Puerto Rico’s main campus.

Barrio Venezuela 1936

Barrio Venezuela 2010

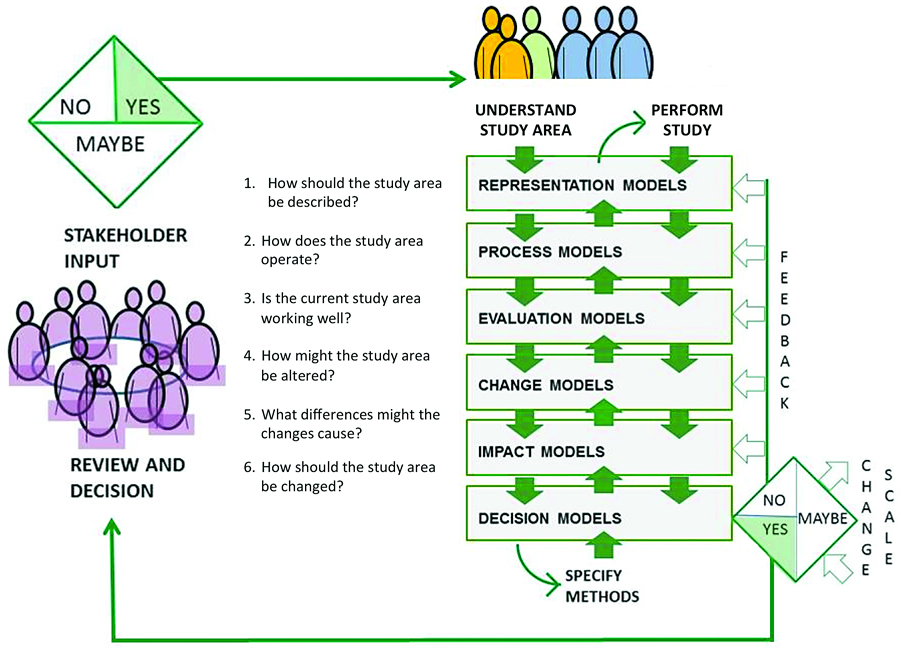

Like many cities in the US Industrial Midwest, commonly referred to as the Rust Belt, Puerto Rico and San Juan have suffered decades of continuous economic contraction. This context of decline requires a different approach to traditional revitalization, renewal, or other planning initiatives that look to put a new face in the otherwise seriously deteriorated urban environments. The Geodesign framework offers the opportunity to tackle the complex problems of decline through local knowledge, values, and priorities while requiring an interdisciplinary team to support the effort of stakeholders. The Geodesign framework uses six questions to guide the workings of the team to:

- Represent place’s physical, ecological, economic, and social geographies and histories

- Understand a place’s functional and structural processes;

- Evaluate these processes from the stakeholder’s point of view (values & priorities).

- Propose change that responded to above;

- Consider the impact of the changes and;

- Finally, reach a consensus towards a shared vision of the future.

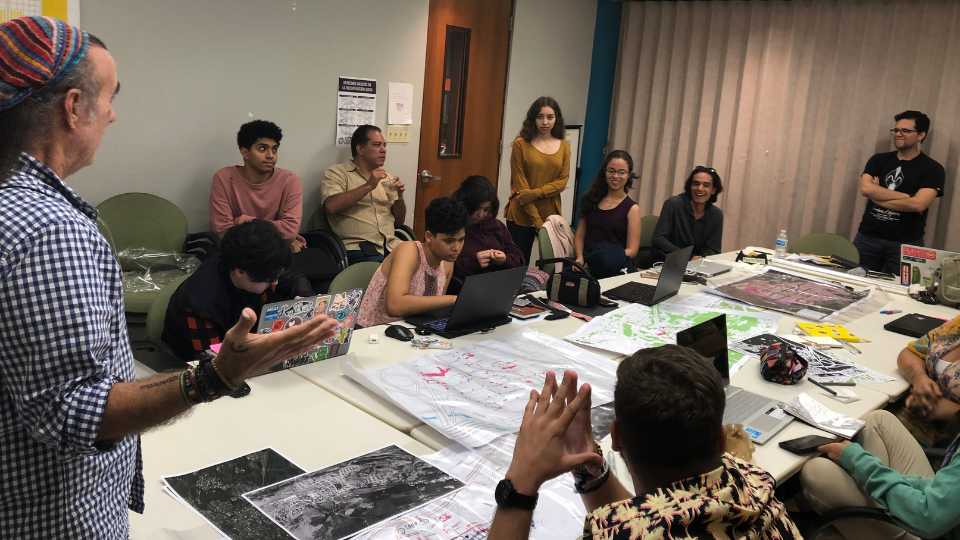

For this project, we hosted three Geodesign workshops at key stages of the process to ensure engagement with the local population.

Representing Barrio Venezuela’s Current Context

The people of Barrio Venezuela are deeply rooted and are a tight-knit group; this is not just an effect of the small geographical location. Social organizations like churches and the Sports and Culture Association play an essential role in promoting activities to improve residents’ quality of life and create a sense of community. A key part of the first Geodesign workshop asked residents to describe their community. Most had a positive appreciation, summarized as community, scenery, and culture. These represent their communal bond, the scenic view provided by the higher elevation, and the highlights of their annual cultural celebrations.

Trust-Driven Evaluation

Trust is an essential component for an adequate evaluation and is also required for effective collaboration. The Geodesign framework is built around resident-collaboration, and a successful Geodesign team will have to build internal and external trust. We were lucky to have the support of the UPR CAUCE’s Community Social Work professors and students. They’ve been working with the community for years. Conserned by the events surrounding Hurricane Maria’s physical impacts, we were able to talk with the community about their needs openly and discover more beyond that event. Most issues stemmed from one primary process, transportation, and the gradual landscape change that severed connectivity with other areas. The amount of cars on the streets puts great pressure on otherwise normal activities like garbage collection, road maintenance, or mail delivery. For example, even moving groceries from available parking to one’s home becomes a significant challenge.

Visions for Change

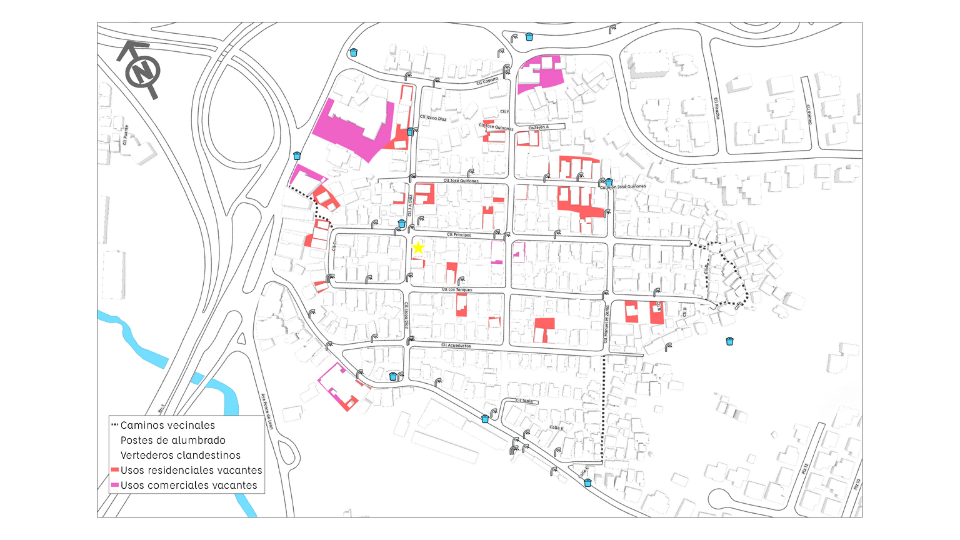

Building upon outcomes from the first workshop, the second Geodesign workshop focused on the community visions for change: Housing, Infrastructure, Transportation, Recreational and Green Spaces. Residents used maps with information generated during the first evaluation workshop and data developed by vacancy, infrastructure, and illegal dumpsite inventories. The residents’ main focus concentrated on rehabilitating existing vacant structures, the development of parking on vacant lots, and repaving pedestrian pathways. All of these are basic needs. The third workshop with an identical purpose was also conducted with students from the University of Puerto Rico School of Architecture Community Design Course. This was a great opportunity to have students exposed to the real-world needs of local residents. During that workshop, students and faculty worked with maps that included residents’ handwritten visions for change, using a clear plastic film overlay. Their approach advanced more significant intervention, taking advantage of the numerous vacant structures within the neighborhood. Connectivity to the Río Piedras town center was another important theme. Here students focused on proposing a greenway that restored physical access to economic and social activities and better public transportation options.

It was inspiring to witness how the Geodesign framework dramatically contributes to understanding local needs for change and stakeholders’ tolerance for change. Although the current declining housing infrastructure presents designers’ with an opportunity to propose more significant interventions, residents’ values and memories of their community provide realistic checks on this and limits to these change proposals.

Residential

Infrastructure

Designing a New Future

Although the emergence of the global pandemic slowed the progress and the contact with the community stakeholders, the work for a better Barrio Venezuela continues. Residents have adopted the fundamental questions of the Geodesign framework. During this past summer, wearing facemasks and physically distancing, a group canvased parts of the communities where some activities made it difficult for outsiders to go ask too many questions. They evaluated their small part of the neighborhood and pointed out its tolerance for change. This most recent activity is one of the most important results of this Geodesign implementation. It has opened the door to establishing collaborative dialogs between design professionals and people with exceptional knowledge. This collaboration is ongoing and will result in Barrio Venezuela taking advantage of the newly generated ideas to guide future developments in their community.

Three years after Hurricane María, communities all over Puerto Rico need to make their voices heard as we enter the planning phase of recovery projects financed by CDBG-DR programs. For Río Piedras, the Geodesign effort will place neighbors, and business owners in a better position to influence visions for change included as part of the recovery. In general, planning processes will significantly improve, focusing on generating trust through local knowledge and priorities; this new approach will find local people ready to engage and meet the challenge.