Author: Laura Solano

A Poverty of Landscapes

Near my office, in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Cambridge, MA, there are major street improvements taking place that include new curbs, walks, road resurfacing, and street trees. I find it ironic that the city chose to make this already verdant and beautiful neighborhood even more so while other far less wealthy areas have so little of the type of outdoor spaces that make cities livable. This isn’t a political statement meant to exclude the rich—everyone deserves to enjoy the gifts that landscapes offer—but more of an appeal to be more ambitious in our efforts to acknowledge and use nature’s unique ability to uplift every human being, regardless of their zip code.

We have known the importance of landscape in the modern metropolis for many years now. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in particular showed us that public parks are both a manifestation and mirror of our democracy, an idea still spawning action in the twenty first century with programs like former Mayor Bloomberg’s expansion of New York City’s parks so that every New Yorker might live within a ten minute walk of one (by 2013 that was true for 76% of the city’s population). The next step in greening our cities must hit closer to home, literally an expansion of landscape within every zip code so that nature becomes inextricably woven into the course of our daily lives. In this approach, all of the corridors and interstitial spaces between buildings become important. Sidewalks, boulevards, intersections, fallow lots, front and back yards, community gardens, and every other piece of urban open space becomes the ultimate borrowed civic landscape.

In 1970, decades before child advocate Richard Louv woke up the world with his important 2005 book Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder, environmental psychologists Rachel and Steven Kaplan began studying the effects of nature on people’s relationships and health. This led to their Attention Restoration Theory in which they posited that the mental fatigue coming from directed attention, employed when concentration was needed to do something that in itself didn’t attract attention (think studying, work tasks), could be restored by effortless concentration of the type that comes from being in nature. The processes of nature—leaves rustling, a babbling creek, animal activity, seasonal changes—are “soft fascinations” that effortlessly draw our attention. The complexity of nature in itself is endlessly interesting and, when exposed to it, we get a mental break from the daily grind and return to it more refreshed than if we had slept.

In 1892, psychologist William James provided the underpinning for the Kaplans work by identifying the concept of “voluntary attention” (what the Kaplans called directed attention) while also noting that natural settings were “effortlessly engaging.” The Kaplans picked up on the “why” of these observations. It’s interesting to note that James’ contemporary, Frederick Law Olmsted “not only understood that the capacity to focus might be fatigued, he also recognized the need for urban dwellers to recover this capacity in the context of nature.” In 1865, the year Olmsted began designing Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Kaplans noted that he “was particularly sensitive to the role of ‘natural scenery’ in restoration: it ‘employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system’.” As usual, Olmsted was ahead of his time, but unfortunately designers and planners would not take serious notice of this phenomenon until nearly a century later when the Kaplans published The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective, which has influenced generations of design professionals.

In contemporary studies much deserved attention has been given to fostering children’s well-being through exposure to nature, which is good, but more attention needs to be given to the adults that care for and surround them. In addressing adults’ “Nature Deficit Disorder,” children will be taken care of too. Many studies look at the benefits of immersion within nature where the landscape is more central than architecture. Perhaps it’s even more important to understand how little nature is needed to get comparable benefits, especially in the inner city, in high population density, and low income neighborhoods. Dilapidated buildings get a lot of notice in these areas, but it’s the scarcity and quality of landscape that grabs my attention in these places, a condition that I have come to think of as “a poverty of landscapes.”

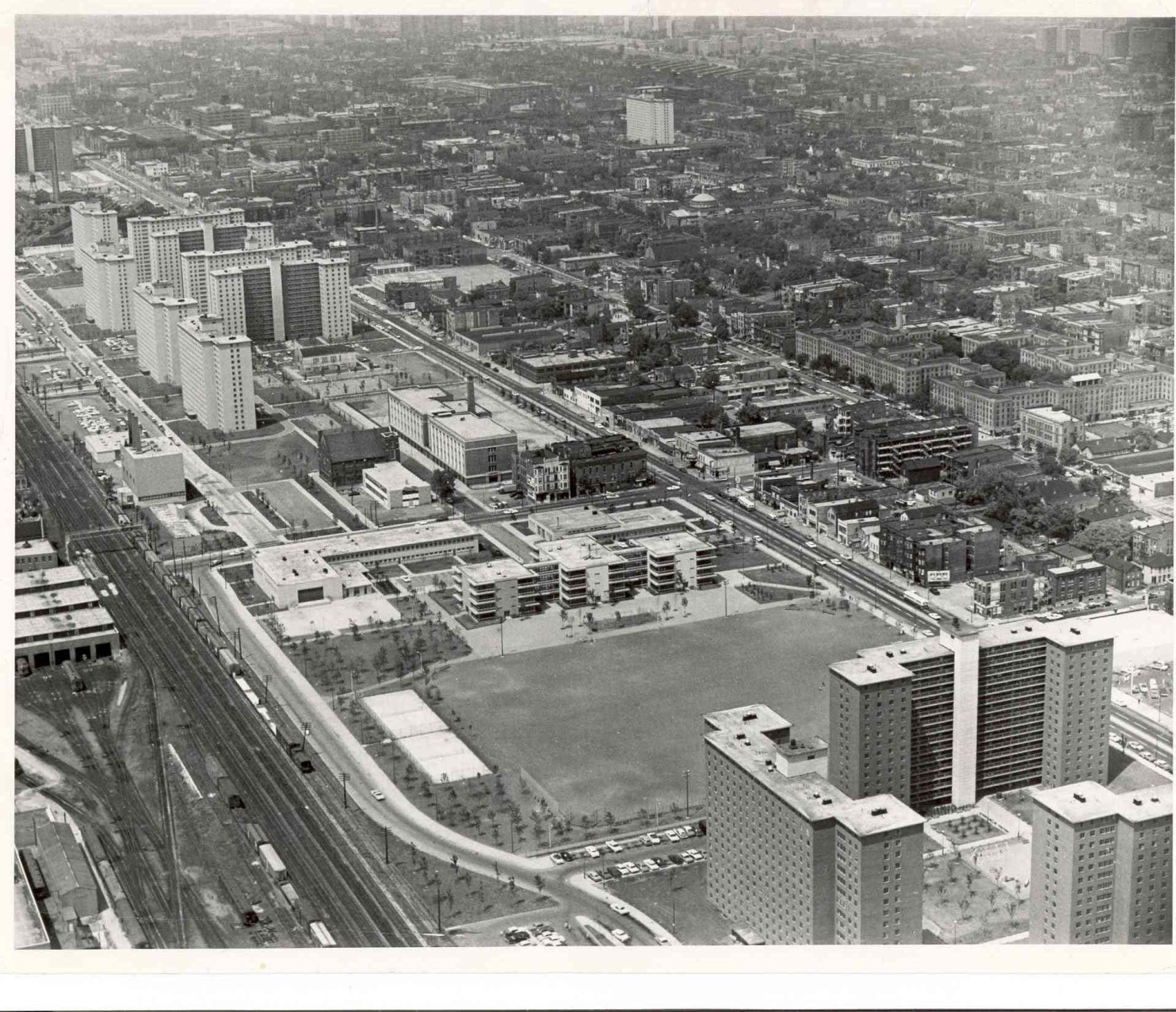

Robert Taylor Homes, Chicago, IL, circa 1963, SOM Architects

Public housing in the United States serves as a living lab for researching the effects that the lack of green space has on the human condition and for answering the question of “how little nature” proves helpful. The itinerant pattern of failed landscapes in public housing, where decline that went unchecked by maintenance spawned an aggressive program of paving over these failures, left behind a mixed legacy of both treed and barren courtyards. Professors Frances Kuo and William Sullivan of the Landscape and Human Health Laboratory at the University of Illinois have compared these different manifestations of landscape in public housing to explore questions like: does vegetation reduce crime; can nature improve self-discipline; does contact with nature improve scholastic aptitude scores; and can nearby nature restore psychological resources needed to tackle life’s critical issues? In their own work at the Robert Taylor Homes and Ida B. Wells Homes in Chicago and their review of sixteen studies between 1984 and 2001, the answer to these questions is an overwhelming “yes.” Using neurological testing, they were able to conclude that all of these skills could be improved by exposure to nearby nature. Seeing, smelling, hearing, and feeling nature every day, even remotely and in small doses, is restorative, helping us face the inevitable stresses that come with living. Perhaps most importantly, exposure to nature helps us to make better decisions about the bigger arc of our lives. So while public housing provides the circumstances for study, the answer to these questions apply to and affect everyone.

Others have built on this type of research, making specific observations with a powerful narrative. Work by Roger S. Ulrich (1984) has shown a correlation between improved surgery recovery time and views of nature from hospital rooms. Reaching beyond the know benefits of street trees in cities—improved air quality, reduced heat island effect, efficiency in HVAC systems, higher property values—a group of researchers from the USA, Canada, and Australia found that people living in well-treed Toronto neighborhoods reported better health and had significantly less cardio-metabolic issues. Taking it even further they equated “having ten more trees in a city block improves health perceptions in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $10,000…or being seven years younger” In a paper entitled “The Effects of Skeletal Streetscape Design on Perceived Safety,” researchers from the Universities of Vermont and Colorado stripped down the complexities of similar past studies to look at the effect of the massing of adjacent buildings and trees on streets. They debunked prior research (Talbot and Kaplan 1984) that people see heavily vegetated areas in cities as dangerous. Instead they found that “streetscapes that were more enclosed by buildings and trees were generally perceived as safer than those that were more open and less vegetated. Skeletal variables are substantially better predictors of perceived safety than household income or Walk Score indicating that skeletal design contributes to comfortable urban environments in ways that are distinct from affluence or broader-scale urban form.”

Central Park Mall, New York, NY, circa 1901

Environmental psychology has a clear message for landscape architects and policy makers alike: we need to expand our notion of urban landscapes and advocate for nature at every turn. Great parks are the heart and lungs of city living but even the smallest landscape interventions also matter to our psycho-emotional well-being. No profession is more responsible and empowered to make our cities livable, but, if we are honest, we fail on a lot of levels to make a convincing case that landscapes are far more than an aesthetic upgrade and therefore indispensable investments. We lack important back up information about the economic benefits of landscape. Unwilling to make our work sound expensive or perhaps unable to make the case, we also don’t convincingly insist that the long-term success of landscapes requires focused care during establishment and an appropriate level of maintenance in perpetuity. On a project by project basis, where outcomes are determined, we can undermine our collective achievement when we make designs that don’t fit the context or that bow to architecture, chose plants of inferior quality or those that can’t withstand given conditions, ignore basic soil and hydrologic performance requirements, make fussy landscapes that can’t be maintained, or experiment without the proper research and testing. As a profession, we need to be more rigorous about looking critically at our own built landscapes to see what didn’t work (or did). All of these mistakes listed above can add to the misguided narrative that landscapes are not as powerful and effective as the research shows them to be. We can do better and there is increasingly detailed and rigorous research on all of these topics that can support us, such as the Landscape Performance Series.

After the United Nation’s World Commission on Environment and Development issued “Our Common Future” (aka, the Brundtland Report) in 1987 to address the growing concern about the political, social, and economic consequences of the accelerating deterioration of the human environment and natural resources, it seemed that landscape architecture’s time had come (high fives abounded) and for sure our contributions since then have been great, influential, and sustainable. But let’s not forget the importance of the everyday. Perhaps there is such a strong correlation between vegetation and positive social behavior because even a single tree carries hopefulness about the future, the potential for change, and maybe even a kind of psychological immensity that allows us to feel like we are part of something bigger. Without equitable access to landscape and nature as part of everyday life, those important associations become impoverished, not only for the most vulnerable, but for all of us.

—

Lead Image: A mother and child in 1997 at the notorious Robert Taylor Homes, since demolished. Credit: Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

Login

Lost Password

Register

Follow the steps to reset your password. It may be the same as your old one.