Author: Linescapes

How to Draw Landscapes (Like a Landscape Architect)

There is a big difference between taking a snapshot with your smartphone or taking time to draw something: the former you will likely forget, and the latter you will remember. Why is that? Drawing forces you to take time and really look at what is in front of you. It is a haptic experience. When you hold a pencil and retrace what you see, you can almost feel the object, its forms and structures. This can especially be experienced when sketching landscapes.

Landscape architects deal with landscapes on different scales all the time. But landscapes are also one of the most challenging subjects to draw. That’s why today we’ll share with you some tips and tricks we find helpful for drawing them.

Tips that will help you improve your landscape sketches.

As designers or planners, we always use drawing with a certain intention. It is a tool. As with every tool, you need to know what you are using it for. Is it to document, to think and design, to communicate or to understand? Different ways to draw produce different results. If you know what your goal is when drawing, you’ll focus on it and produce better work.

When we draw landscapes on our trips or travels, we usually do it to understand what we see. Through drawing, we try to perceive the logic of the landscape, its structure, its elements and the connections between them. This enables us to grasp our environment better.

Why is drawing landscapes a challenge?

Landscapes are a complex subject to draw. Contrary to architects, landscape architects have to depict a subject that cannot be summarised as one finite object. A building is static, its boundaries clearly defined. A landscape, on the other hand, defies a clear definition of borders. It can be seen from many angles and always appear different. It’s best perceived when moving through it. So what to do when we try to depict it on a 2-dimensional surface?

Abstraction

There is a set of tools we can use to tackle the challenge. The most powerful tool we can apply is abstraction. Rather than attempting to depict the natural visual reality, which is immensely complex and hard to read, we can concentrate on the elements and the underlying structure of a landscape. Through the process of abstraction, we decide which elements of the landscape we want to draw and which we leave out. This depends on what exactly we want to communicate or record with a drawing.

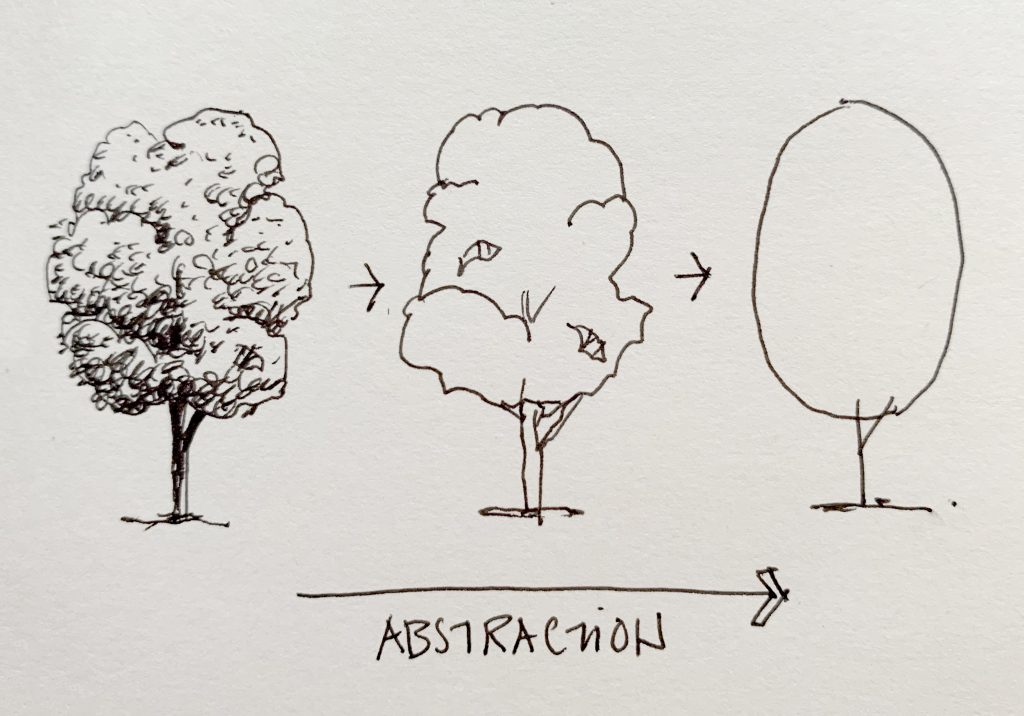

Three stages of an abstraction of a tree.

So how exactly do we abstract a landscape? By using symbols instead of naturalistically depicted landscape elements. Abstracted symbols are easier to draw and immediately recognizable. Landscape elements like trees or mountains are archetypal images. If we draw a simple circle with a line extending down from it, our brain will immediately recognize a tree. And not only our own brain – most people in the world, no matter their cultural background, will recognize that symbol as a tree.

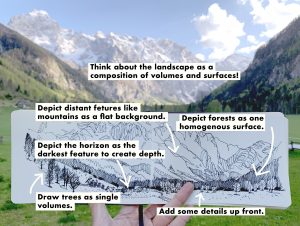

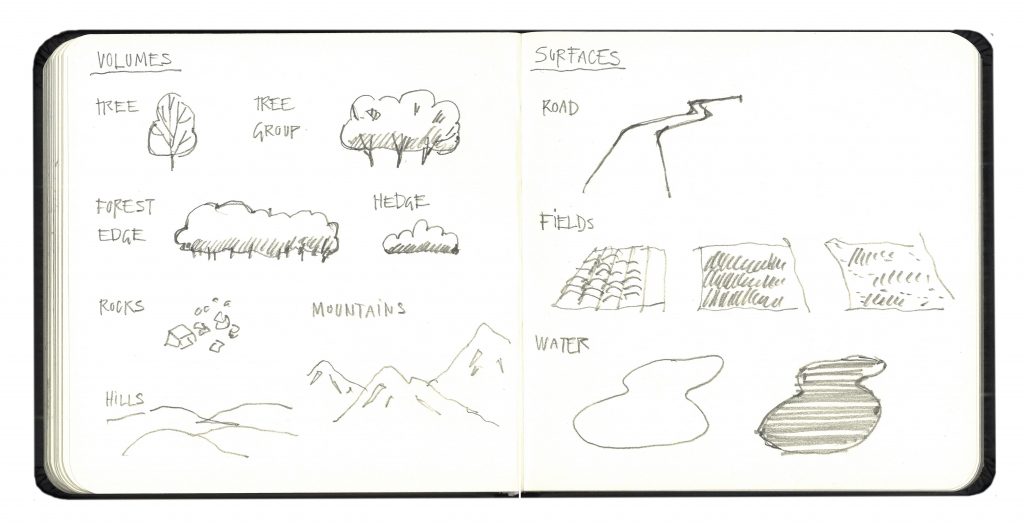

A sketch of volumes and surfaces from which a landscape is composed.

Surfaces and Volumes

The second useful trick that will make drawing landscapes easier for you is to think in terms of volumes and surfaces. It’s similar to the kind of thinking applied when designing a landscape. Every open space is composed of flat surfaces upon which volumes are arranged. This also applies in a natural landscape. Roads, meadows, and fields are perceived as surfaces, while vertical structures such as shrubs, trees, and hills are perceived as volumes. Thinking about them in this way will help you when drawing.

Think of landscapes as a composition of surfaces and volumes.

If you’re interested in more tips on drawing landscapes and want to delve into the topic further, you might find the video on drawing landscapes we did useful:

The final tip for drawing landscapes we can give you is to be aware that drawing is just a tool. It is one of many tools, like physical models or CAD, that helps us in our work. Don’t consider sketches to be artworks. Since a sketch is only a means to an end, it doesn’t have to look good. It just needs to be useful to you.

Improve Your Drawing Skills: Perspective and Proportions

CAD has been a standard in the profession for decades, planing in virtual reality is around the corner and everyone can take snapshots of views they want to remember with their smartphones. But we want to talk to you about drawing, sketchbooks, and tips for constructing a perspective. Why is that?

Let’s make one thing clear: all of the new digital tools bring amazing value to our professional work and we’re not suggesting going back to the drawing boards and rulers. But being able to transfer one’s thoughts from the mind to paper in a quick and confident way can be very beneficial for a number of reasons. First, a quick sketch is still worth a lot as a design tool. The lightness of the free-hand drawing enables us to think with it and explore different variants and possibilities without being constrained by the stiffness of a digital tool. And second, it’s a great way to spontaneously communicate the image in our head to others. We’ve written on Land8 about the topic for drawing in a previous article, “3 Reasons Why You Should Start Drawing Now”.

Now that we have hopefully convinced you that sticking to a physical pen still makes some sense, let’s look at how you can improve your drawing skills. In our last article, we showed you how to beat that scary blank page and start drawing. This time, we want to dive a little deeper into the topic with tips for improving your drawing skills. We’ll look at drawing space realistically and how to use perspective and proportions.

Perspective

Us landscape architect usually want to depict space with our drawings. Physical spaces are, after all, what we deal with professionally on a daily basis. This can be done in different ways. The most common one is the abstraction of 3D space onto a 2D plan. Another very common way is a perspective view. It’s way more realistic since it mimics our eye-height perception of space. But a perspective is also an abstraction because it’s a flattening of that perception, characterized by depth and movement onto flat paper.

Let’s look at some terms that constantly keep popping up when talking about perspective. You just have to remember these following few, and you’ll be able to grasp what perspective is all about:

- Horizon – the line where the sky meets the ground. In a perspective drawing, it’s also an imaginary line on which everything that is as tall as the observer lies. For example, if the observer is standing on the ground, all the people in the perspective drawing (assuming they are as tall as the observer) will reach up to the horizon line.

- Vanishing Point – the point where all lines that are parallel in 3D space converge on the horizon line. For example, if you would extend two parallel sides of a cube, they would intersect somewhere on the horizon line.

- Construction Line – simply a helping line with which we construct our perspective drawing. We often have to expend these lines all the way to the horizon in order to find vanishing points.

You might have heard about one point, two point, or multi-point perspectives. Their name refers to the number of vanishing points a perspective view has. But in essence, they are all the same. The difference between them is that the objects we are looking at are either all placed parallel to each other and parallel to the observer (example: houses on a street) or they are not. If they are all parallel, all their sides converge in one vanishing point. However, if they are not standing parallel to the observer, they have more vanishing points. So, the more different individual object positions there are in a perspective, the more vanishing points there will be.

Proportions

As we have seen above, the perspective can be a tool for accurately depicting spatial situations. But in order for us to be able to do that, we need to get the proportions of a view right. The challenge is to look at the view and then re-scale what we see to fit it on paper. If we want it to look “right”, the elements in the drawing have to stay correct size in relation to each other. To be able to do this challenging mental process, we use a technique called “sighting”. It’s a classical trick artists have used for centuries to depict their scenes in a more naturalistic way. We explain this technique in an easy way in the following video:

We hope that these tips will help you on your way to starting or improving your drawings skills. Always remember – drawing is, in the end, just a tool. But it’s a good one. That means your drawings don’t need to look good, they just have to work for you.

How to Start Drawing – Simple First Steps

“I wanted to start drawing again, but I just never seem to find time for it” is a sentence we regularly hear from our colleagues. Obviously, many people would like to draw. Maybe they have fond memories of their student years when they were using sketching for design much more often or hand-drawing might have even been on the curriculum. But we believe that drawing is still a very viable tool for every designer and it’s worth picking up again, even if you haven’t been doing it for years or you want to start from scratch.

Why draw?

Picking up anything new is always a challenge. One has to have reasons for it and a good amount of motivation. We’ve recently written on Land8 about the motivation for drawing in “3 Reasons Why You Should Start Drawing Now”.

Firstly, hand-drawing has recently experienced somewhat of a revival in the profession. Many entries in landscape architecture competitions have turned from realistic renderings towards more abstract visualizations, such as hand drawings and illustrations. These more abstract ways of visualization sometimes manage to catch the essence of a landscape architectural work better than a high-end rendering.

Secondly, drawing is an essential tool in the design process. It is the most simple and direct way to record a thought of the designer. But it’s even more than that. Sometimes, the drawing talks back to the designer, helping him or her better understand the shaping idea on the paper and develop it further.

Thirdly, it’s a way to analyze and observe the environment. Taking the time to carefully trace the lines of a view of the landscape forces us to think about its structure and building blocks, the relationship between them and ultimately understand it.

How to start drawing

We went through some reasons that we hope might motivate you to start drawing. But now what? Where to actually start? You have a sketchbook and a pen and now a blank page is staring at you? Well, let’s break the ice. We talk about how you can start in the following video:

A very important thing to note is that after breaking the ice, you have to create a habit if you want to stick to drawing. Here’s what you can do: we advise everyone that after starting, you come up with a plan or a challenge for yourself. Something like a sketch a day or drawing for half an hour every week. It’s best to start with small steps and work your way up slowly. Once you have established a habit, it’s not hard to expand on it and invest more time and energy if you want to.

The Basics of Drawing

The drawing is a process of recording your thoughts and observations on a 2-dimensional surface. It’s actually quite a complex task for our brains. It requires immense abstraction capabilities, for we are representing something 3-dimensional on a 2D surface. But don’t worry. Most of these complex mental processes are occurring subconsciously. All you have to do is observe, hold the pan and move your hand. Your brain and body do the rest. And as you practice, they get better and better at it.

Training your hand is a very good place to start. And the best way to do it is by repeating the basic building block of a drawing – the line. It’s like starting to learn to play a new instrument. You start by practicing single notes, not the whole of Bach’s Cello Suites, and merely train the coordination between your mind and your body. We suggest some basic exercises in the video How to Draw Lines:

When you’ve done several pages of lines and already feel like they torment you in your dreams, it’s probably time to move on. Once the hand has gotten somewhat accustomed to holding and moving the pen, it’s time to start observing our environment, thinking about it and recording it on paper. A good first step is drawing simple objects. They are easily understandable forms that are a great practice for your eye-brain-hand connection. When we draw them, we are forced to observe them, reinterpret them and then record them on paper. Need some good exercises to start drawing objects? We have just the video for you:

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this article and hope we’ll keep you busy for a while! In our next article, we’ll dive into 3D space, the actual subject of a landscape architects work. Meanwhile, if you are curious where to continue, you can always see more on our YouTube channel.

Before you go off drawing

We have a final tip for you. When learning something new, never compare yourself to others, compare yourself to you from yesterday. This won’t scare you away at the beginning and will still keep you going later once you have truly mastered it. Because you can always be better than yourself from yesterday.

Different Attitudes at the Landezine International Landscape Award Ceremony in Hamburg

On the 13th of October, the LILA (Landezine International Landscape Award) was awarded in Hamburg, Germany. The day-long event held at the Hafen City University was titled “Attitudes in Landscape Architecture”. Although it was not a symposium trying to find answers on a certain topic, the lecturers and discussions indeed offered a view of different attitudes towards the profession and its different roles in society. The talks spanned from the political role of the profession, interdisciplinary and all the way to private gardens as an archetype of the landscape architectural work.

Discussion between Ken Smith and Catherine Mosbach, mosbach peysagistes, Winner in the Office Category

The LILA award is presented by Landezine, the renowned web portal for landscape architecture works. It was awarded for the 3rd time this year and has drawn a surprisingly large pool of applicants. The international jury composed of visible names in the profession, such as Ken Smith (Ken Smith Workshop), Sylvia Karres (Karres en Brands), Thorbjörn Anderssen and Gery Hildebrand (Reed Hildebrand) among others. Awards in three categories were presented: office category, garden category, and project category.

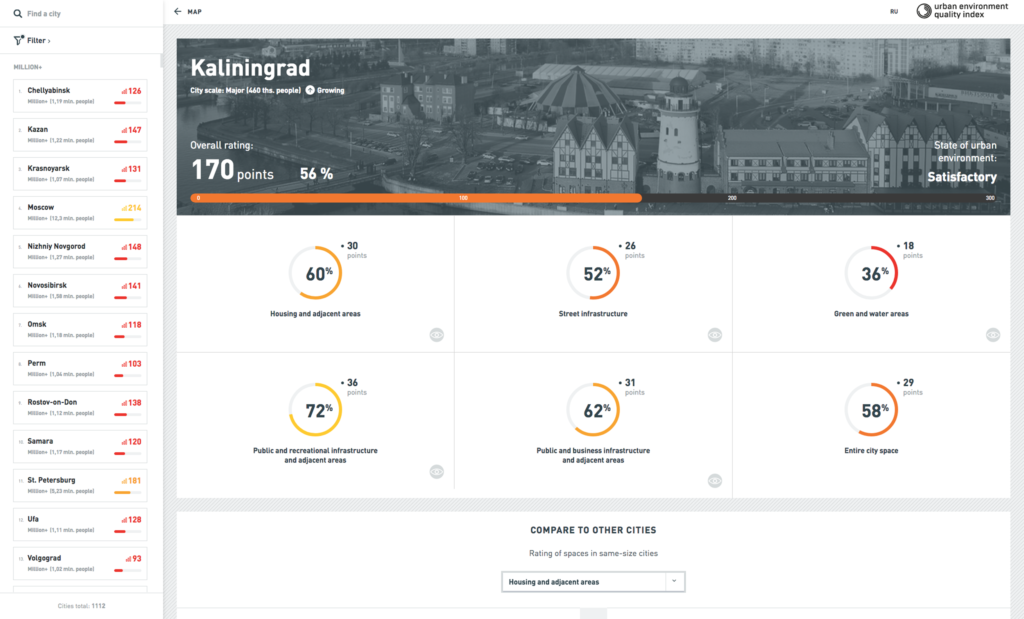

Special mention in Office Category: Strelka KB, Urban Environment Quality Index Analysis

An interesting category of the LILA prize is the office category. It enables offices to enroll with their work, that does not necessarily include planning. It pushes the boundaries of what landscape architecture is. An example of such an office is Strelka (Russia), that was awarded the special mention in the office category. The CEO of the 300 employees large office from Moscow, Denis Leonitiev, introduced the different areas of expertise Strelka works on, such as research, developing competitions, and educating future professionals. Their work includes creating guidelines designing public streets for the city of Moscow, as well as overseeing and managing the competition and development of the Zaryadye Park. Regardless of whether they are in a role of a politician or a planer, as long they are a part of a project they mix different professionals together, often working with foreign landscape architecture offices and bringing them together with local professionals to realize a project. Spatial problems aren’t addressed just on the level of project planning but systematically at the level of the system of the state.

Special Mention in Garden Category: Salaam House, Kenya

A strong contrast to the first half of the event was visible when the winners in the garden category presented their work. The Nairobi (Kenya) based office The Landscape Studio presented by Chloe Humphreys, which was awarded a special mention in the garden category for the Salaam House garden, showed a different attitude and approach to landscape architecture. Instead of political debates around public space, there was talk of senses, light, smells and the meaning of a garden and community around it. The presentation by the winner in the garden category, Sean Coen (Coen + Partners, USA) stroke a similar tone. Coen talked about senses, illusion, and magic in the landscape, the love for his work visible in every sentence. “Find what you love inside landscape architecture and make it a part of your life,” was his advice to the students present in the auditorium.

Winner in Garden Category: Lake Marion Private Retreat, USA

The focus of the two offices on the archetype of the profession – the garden, triggered the discussion about man and his relationship to nature. Both Humphreys and Coen agreed that they do not try to mimic nature. “Trying to copy something so powerful as nature is insincere,” Humphreys stated.

“Trying to copy something so powerful as nature is insincere”

The same question of man-made landscape and its relationship to nature reappeared in the last presentation of the day by Georges Descombes. He represented Descombes Rampini (Switzerland), the office behind the restoration of the river Aire near Geneva, which was awarded the best project award.

Winner in Project Category: Renaturation of the River Aire, Geneva by Atelier Descombes Rampini, Group Superpositions, Switzerland

Descombes’ presentation fittingly summarized the whole event. Different attitudes towards the landscape had to be implemented in order to reach the project goals. Hydrology, ecology, and design, from large to the smallest scale, where combined to create a functional and yet poetic place. “When doing a project, you have to go to the edge of what you know,” explained Descombes, who had to reach out to other professions in order to realize the project.

Descombes described the project as “3rd nature” – a step beyond the human overlay over the landscape. “Not a renaturation, but a fabrication of a new ecological system.” The project is loyal to that paradigm and sincere in its design language. In this, the project is also political – forcing us to rethink our attitude towards landscape.

“Not a renaturation, but a fabrication of a new ecological system.”

The event did not seek out to discuss or solve a certain topic by the end of the day. Nevertheless, interesting discussions followed each presentation. Together with the lectures of the winners, they offered an overview of the broad span of methods, viewpoints, and attitudes landscape architects can take when addressing their work.

LILA has proved again to be a serious award, growing in its global importance for the profession. But it is also a relaxed event with the goal of networking and sincerely applauding other colleagues, who have with their work managed to push our profession a step further.

3 Reasons You Should Start Drawing Now

When is the last time you packed a sketchbook and went drawing outside? Sitting down, really observing a place, understanding it more with each traced line? Maybe you’ve been drawing during your studies and stopped because you do not have the time anymore. Or you might be new to hand drawing and want to learn. We strongly believe hand drawing is something every landscape architect can benefit from. That’s why we’d like to share 3 reasons why you should definitely pick it up:

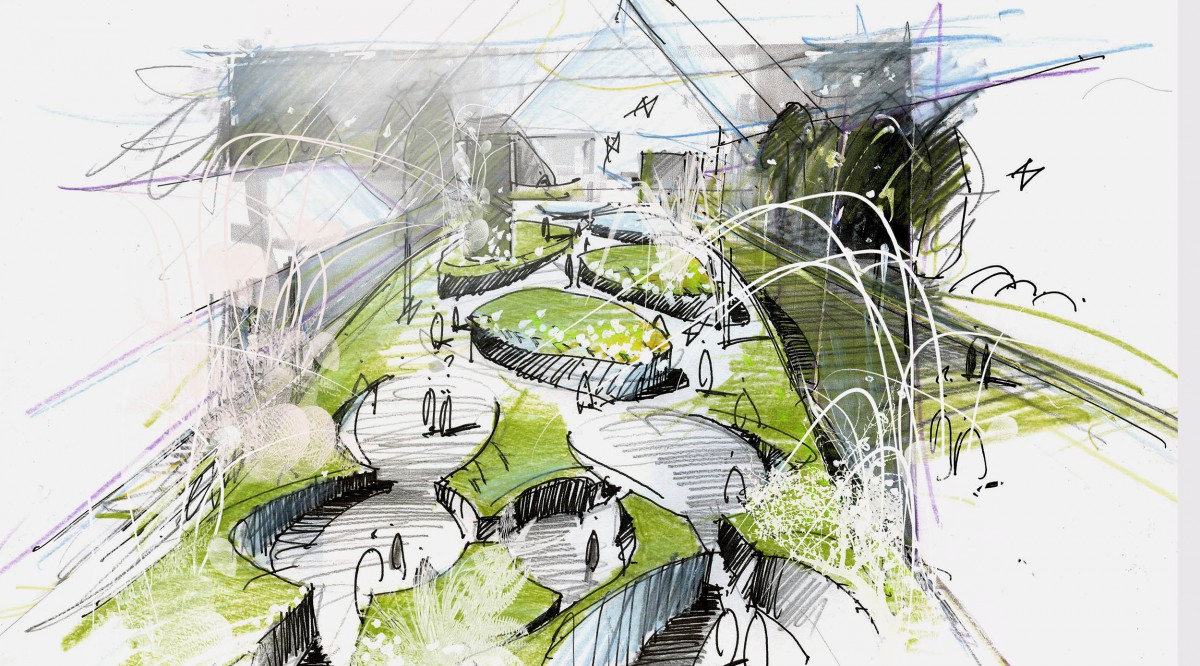

H+S+N: Strategic vision for Arnavutköy, Istanbul

1. A New Trend

Think five years back – a brief scan of competition entries in architecture and landscape architecture would show almost nothing but photorealistic renderings or photoshop montages. It was an attempt to come as close to the visual reality that is suggested to get built as possible. However, recent architecture and landscape architecture competitions have started to show another trend: abstract collage-like visualizations with strong colors that try to convey a feeling rather than a spatial configuration. It appears to indicate that a photorealistic representation has reached a point where it is so ubiquitous that designer seek other tools to convey their ideas more abstractly. Amongst different presentation techniques, hand drawing is emerging as a great option.

A good quality of hand drawing is that it can convey two things at the same time very well – a spatial representation as well as emotions, a feeling of a place. And it achieves both those things at the same time through a level of abstraction. To show more, a hand drawing goes one step back into abstraction and thus lets more room for other information. It focuses on the message it want to convey and at the same time allows the viewer space for imagination. It might even be a smarter tactic, since the viewer (the client or a competition jury) will fill in the blanks him or herself. That’s why we see the trend of returning to hand drawing as positive.

In Germany, for example, many competitions nowadays require a sketched visualization technique (“skizzenhafte Darstellung”) for spatial representations. It created a demand for people who can “still” draw. It seems that hand drawing as a craft as started to gain value again. While it is not necessary to jump on every trend train, it makes sense to be aware of it. Who knows, hand drawing might even be your niche!

Le Balto: Competition entry for Insectarium, Montréal, Canada

2. Drawing is Understanding

Hand drawing is a powerful analytical tool. When you draw a view, it always demands watching and observing it closely for an extended period of time. At the same time you try to abstract the view in a form of a sketch, repeating the forms, thinking about their proportions and roles in the whole. While doing so, you are consciously and subconsciously analyzing it. You will see more of the view, understand it better, and even remember it much better!

Take a second and think about a view you once made a drawing of. Try to remember what it was like to draw it. You can remember quite a lot of details about it, right? That it because you took your time to observe the view and because your hand “remembers” as well. An interesting fact is that our memory works on different channels. We remember things through auditive, visual, and kinesthetic stimulation. When drawing, you experience something not only as a visual information, but by the movements of your hand experience it kinesthetically as well. You are imprinting it into your mind through more than one memory channel.

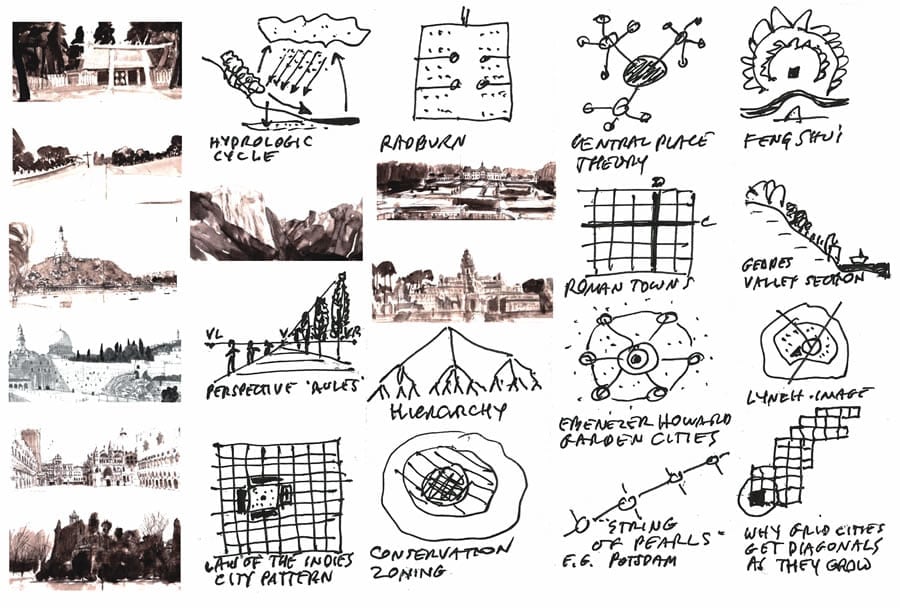

Carl Steinitz: Travel Sketches

3. A Tool for Design

Hand drawing has been an integral part of designing almost from the beginning of design itself. As soon as it was necessary to envision something before one actually did it, drawing became a simple solution to do that. It’s an abstracted model of an idea onto a 2-dimensional surface.

Countless drawings are made all the time when ideas are being designed. The more trained the hand is, the simpler and faster it becomes to translate these ideas onto a piece of paper. But there is more to it. A drawing isn’t only a process of recording and storing design ideas. It has another important role in the design process – when the designer looks at a drawing he or she made, the drawing communicates back. It allows the author to imagine the planed object, evaluate it and draw it again. This journey between the designer and the drawing goes back and forth, the designer changing the drawing and in return learning each time from it. By the end of this process the final design might be completely different than the first idea the designer had in his mind. It means the drawing teaches it’s author.

Drawing is not the only design tool available to us, but it is a simple, yet powerful one. It’s the most direct translation of thought into form available to someone designing.

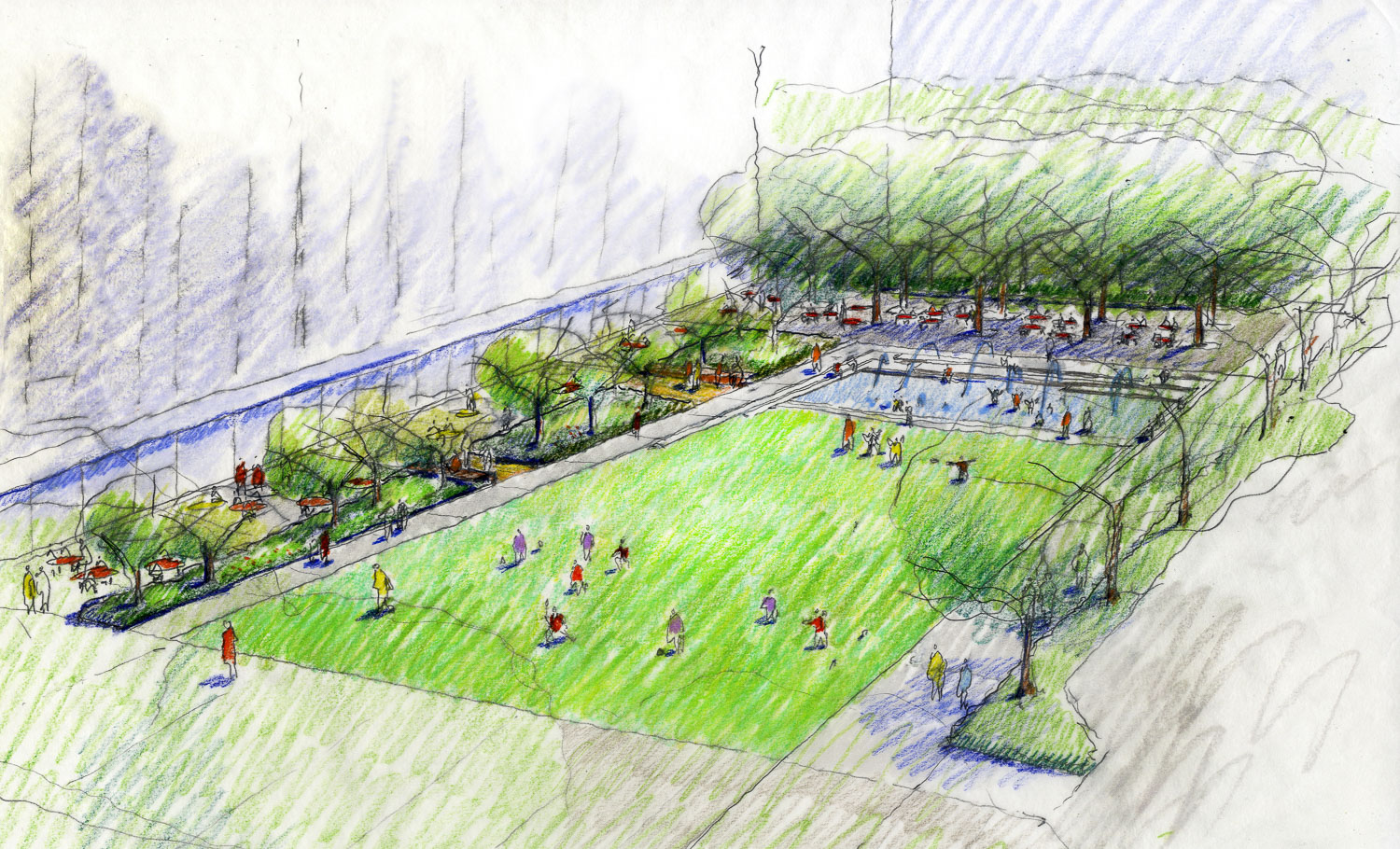

GGN: The Spring District Park

We hope we might have ignited a spark of interest for drawing in you. In the end, there is also another reason to do it and it is perhaps the most important one: drawing is fun! The beginning is harder, yes, but that’s the case with everything when you start. The great thing with drawing is that you will notice your improvement quickly! To help you do that, we will continue with a series of articles on Land8 on how to draw. If you want to start learning, you’re are welcome to do it with us!

Thorbjörn Andersson: Lund Institute of Technology Campus Park