Author: Meade Mitchell, PLA

Authentic Nature is Our Greatest Amenity

On a sticky Saturday morning, a pickerel frog lets out a slow, steady snore as he perches proudly in his newly found, tiered-pond paradise. Just below the water’s surface, dozens of intrepid tadpoles dine on algae — while others succumb to schools of hungry fish on the prowl for a morning snack. Aquatic plants shimmer in the sunlight, as ever-evolving shadows cast from bald cypress branches sway to wind-swept rhythms across the wetland wonderland. A great blue heron drops in for a closer look when the proud pickerel frog catches her eye.

Just beyond this nature show scene, the smiling faces of children explore the setting and make memories they’ll cherish for ages. Some wade in the muck searching for crawfish and frogs, others skip stones and trade playful taunts in friendly competition, while still others stack rocks and sticks to build whatever their creativity can concoct. The scene is a throwback to days of yore when summers and weekends were simple yet whimsical, nearby and nature-filled, immersive and imaginative.

Surprisingly, the setting of this informal play is not a school-sponsored visit to a local nature preserve or state park, nor is it the aging memory of exploratory children raised near marshes and coastal bends. This lush and thriving ecosystem exists right in the middle of a master-planned community in greater Houston — and for some fortunate kids, the journey from home to natural exploration doesn’t even require crossing the street.

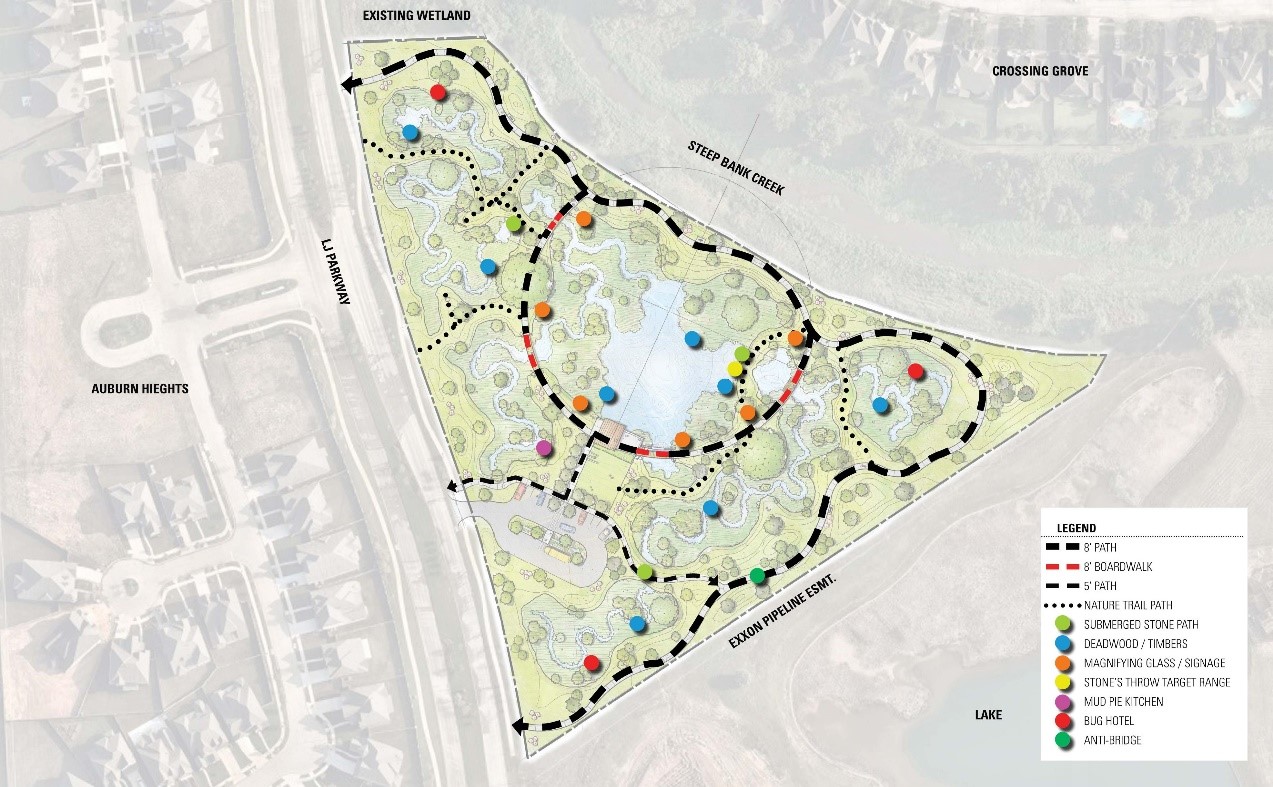

This neighborhood park exists at Riverstone, a master-planned community in Fort Bend County located approximately 25 miles southwest of downtown Houston. The 9-acre park includes roughly 4.5 acres of wetlands, which were created partly to fulfill requirements to replace wetlands lost to development, but also to encourage interactions with nearby natural settings in a way that creates memories and fosters a love of nature — and, yes, that often means getting a little dirty.

Engagement Diagram | TBG Partners

It represents a paradigm shift: moving beyond playgrounds and splash pads to more naturalistic amenities — and encouraging active engagement with them. In Houston, where a normal year includes roughly 50 inches of rainfall, the need for stormwater detention areas is paramount, and you can find lakes, ponds, and wetlands serving as visual amenities throughout the region, often with a boardwalk and interpretive signage, but this is the hackneyed “look, but don’t touch” approach.

Taking a group of kids down a boardwalk, single file, and letting them read a sign or observe a bird off in the distance does not celebrate nature. Letting them get in the water, dig in the mud, throw rocks, build a shelter out of sticks, and other types of spontaneous play are sensory experiences that allow them to feel they are part of the environment — and helps inspire a conservation-minded ethos that can shape future attitudes toward stewardship.

The Riverstone development team’s perspective on play environments has evolved greatly over the years, and their support in trying new approaches has been invaluable. Several years ago, the idea of repurposing logs as climbing elements in a traditional playground drew apprehensive looks, but it was a hit, and then our next play area included a tree house, barefoot walking paths and a custom play feature envisioned as an immense grasshopper. But the wetland park was the biggest leap of faith yet — the boldest, most unconventional play environment we’ve created together — and its ability to engage kids, and adults, with nature brings our design team immense pride.

When we first started the design process for the 9-acre wetland park a couple years ago, the now-thriving ecosystem was nothing more than a flat parcel of St. Augustine grass and weeds devoid of any allure. We knew half the parcel needed to be converted to wetlands to offset similar lands lost to development, but aside from that, it was basically a flat, blank canvas; there was essentially 12 to 18 inches of fall across the entire 9 acres.

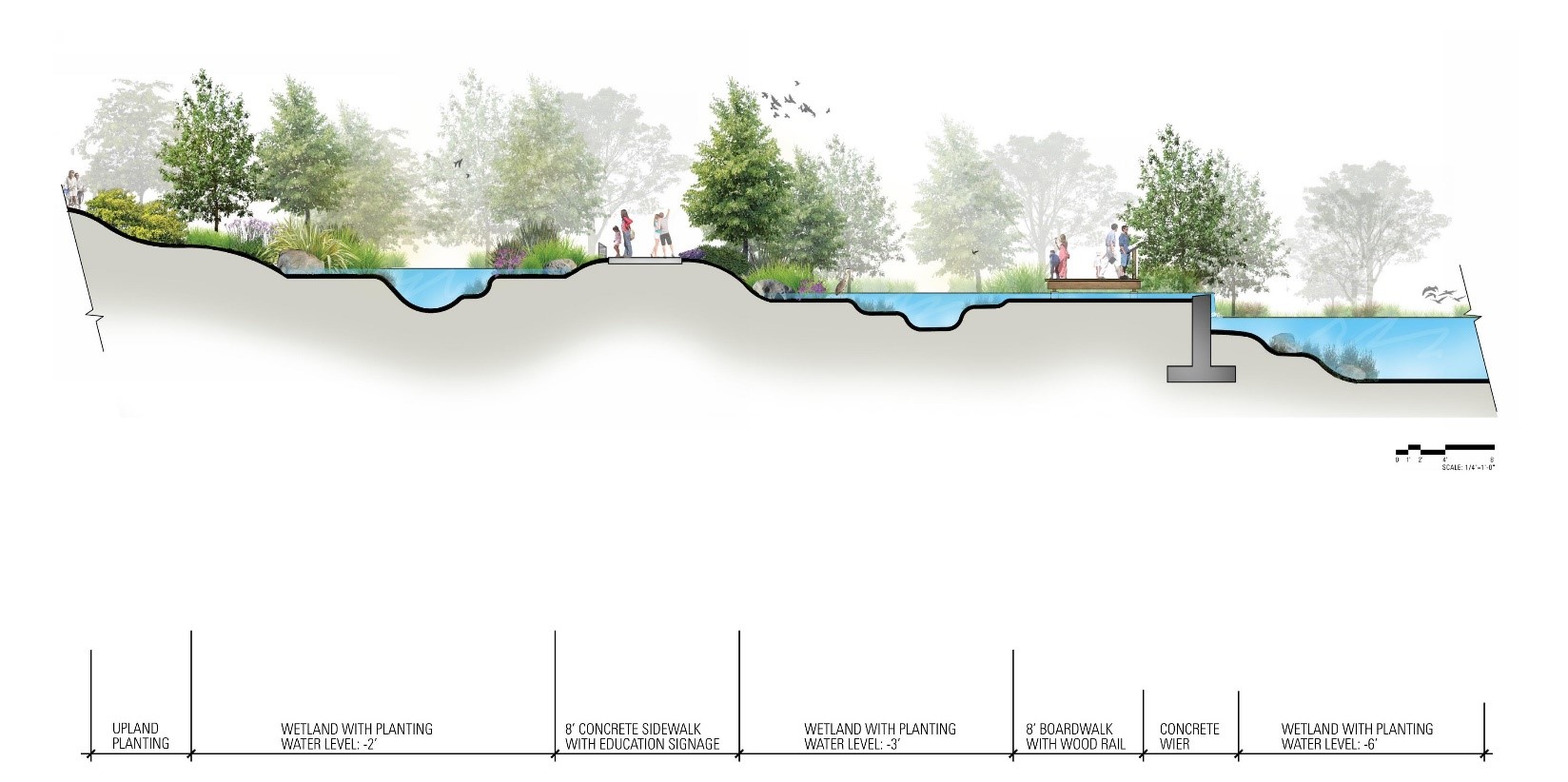

Section Depicting the Wetland Rooms | TBG Partners

We needed to create low areas that collected water, but to make it more explorative, like stumbling upon new environments, we made a series of ponds with slightly different elevations that are hydrologically connected through balance pipes. Each pond is a little bit lower than the one adjacent to it, and the lowest pond is about five feet beneath the highest. A series of pipes with make-up water — gray water from a service water treatment plant — ensure the ponds never go dry. Oftentimes the water sources are hidden, but other times we made them more conspicuous, like bubbling out of a little circle of rocks, an artesian well look, or as a series of little waterfalls, all of which accentuate the water’s movement and create a peaceful white noise. All the ponds maintain about 6 to 12 inches of water, except for the main central pond, which goes down about 5 or 6 feet deep.

Initial Concept, Activity Nodes, and Water Level Pond Depths | TBG Partners

Programmatically, we split the park into a more passive area for quiet engagement that has a little walking trail, a bridge and a waterfall, while the other section is much more interactive and playful. It’s unfortunate, but these days we largely have a generation of nature-phobic parents and children; kids today are almost imprinted with this idea that nature’s not for them. Thus, in order to encourage contemporary kids to explore, you almost have to roll out the red carpet and invite them into the natural areas.

Photo by TBGer Hunter Jayroe

Artesian Well | Photo by TBGer Hunter Jayroe

Stone Skipping Beach | TBG Partners

So, we made pathways with partially submerged stepping stones that go out into the ponds and encourage taking some risks. We put tons of rocks next to a beach-like pond edge and set up distance markers at 20, 40 and 60 feet out — and recently when I was out there, the stone-skipping beach was thinned of its rocks and the targets were peppered with dents. Elsewhere, we elevated a platform above a muddy area that encourages the kids to get a little dirty in what we think of as the mud pie kitchen.

Interpretive signage exists throughout the park as well, and there are many tall, interactive pillars with educational text and pull-out shelves, the top of which is a large magnifying glass to closely examine whatever natural elements users find. Elsewhere, a root wall installation showcases soil and root systems of various plants and grasses, with tall plexiglass walls providing a sneak peek into these normally subterranean phenomena.

Interactive Pillars (Designed by TBG’s Environmental Graphics Team)

Root Wall Installation | Photo by TBGer Hunter Jayroe

Following construction completion, during the critical evaluation phase when we analyze operations and maintenance, we engaged a biologist to help assess our wetland plant palette. Our goals included having durable plants — species that could potentially take abuse from kids but recover quickly — that also attract wildlife to the area and showcase seasonal impact. Working with the biologist was informative and helped us refine our palette, but it also was a balancing act. To a biologist, a snake is just as valuable as an egret, but as a landscape architect focused on creating places that engage humans, we recognize most people don’t want to see lots of snakes in their recreational setting. So, in some ways, it’s almost like a retail display of biology and ecology — celebrating the beauty of nature, but in somewhat more purposefully refined manner.

Photo: TBG Partners

The park got its first real test a few months after it was installed when Hurricane Harvey hit the Houston area in late August 2017. The tremendous volume of rain filled up the tiered ponds so there was no differentiation between the various levels, but the water didn’t exceed their banks because the system was set up to overflow into pipes that discharge into the main lake system. It stayed in a state of inundation for a couple weeks, but once the waters receded, other than muck on the bridges and trails, everything was perfectly fine and the plants immediately bounced back. It did its job as intended.

Creating the wetland park at Riverstone has been a great learning experience and truly rewarding endeavor. Allowing kids to play in their own natural neighborhood is so important, especially in our contemporary plugged-in society, as it helps create an enduring appreciation for nature in a way that becomes sacred. Moreover, when we think about recreational settings, water should be thought of as a habitat — not something to neutralize and eliminate all living things from — and treated as an amenity that people can engage and explore.

After all, nature play isn’t a postcard — it’s a chance to become absorbed in the natural environment, take some risks, develop skills and learn how things work. We should encourage kids to go ahead, pick that flower, walk on that log over the stream, tip that rock over and look at all the bugs crawling underneath. Wade out into the shallow waters and look at all the fish and tadpoles swimming around and, sometimes, if you stand still long enough, a majestic heron might just swoop down alongside you and join in the fun. That is true nature play.

Bioswale | TBG Partners