Author: Mitchel Loring

A New Method for Designing with Social Media Data

Urbanist William H. Whyte famously quipped: “It is difficult to design a space that will not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished.” And it’s true. Many of our cities suffer from underused spaces. Luckily for those of us who lack the time or Whyte’s skills in urban observation, publicly accessible social media data now provides us with rich insights into public perception and usage of urban civic spaces–if you know how and where to look.

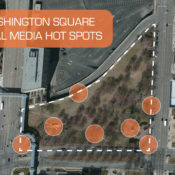

Although social media-based analysis is by no means a replacement for traditional methods of analyzing public spaces, it’s a great way to gather massive amounts of recorded, real-time data of individual thoughts and reactions to a space in a specific time frame. I developed and tested this social media-based methodology of analysis on Washington Square, an underperforming space in Kansas City, MO, as part of my master’s report titled “Capturing the Buzz: Social Media as a Design Informant for Urban Civic Spaces.” The report’s findings turned up solutions for not only Washington Square, but for Kansas City’s goals for the area as well.

Civic spaces are important nodes of urban life. To understand why certain civic spaces are successful and others are not, I collected Instagram and Twitter posts from the geographic boundaries of Washington Square and three other civic spaces: Civic Center in Denver, CO; Jamison Square in Portland, OR; and Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, PA. These civic spaces were chosen for comparative analysis because they exhibit characteristics similar to Kansas City’s goals for Washington Square. Using content, experiential, geographic, and textual analyses, the social media posts were studied to discover the repeated themes that people are documenting in these parks. This data was synthesized to create solutions for the redevelopment of Washington Square.

One of the most interesting findings from this research was the dichotomy between the similarities of Washington Square and Civic Center compared to the similarities of Rittenhouse Square and Jamison Square. Both Washington Square and Civic Center are surrounded by relatively low surrounding population density within a quarter mile radius, unlike Rittenhouse Square and Jamison Square, which are surrounded by a higher-density residential population. This wide range of population densities is displayed in the maps below.

I also noticed certain social media patterns between these two groups, and separated them into two “experience” categories. In the Washington Square/Civic Center group, the social media data indicated that people are most frequently engaged in active experiences during their time in these civic spaces, as noted by the “Event/Activity” category in the pie charts below. In contrast, the social media data in Rittenhouse Square/Jamison Square group indicated that people are more frequently participating in passive experiences, such as relaxing or attempting to capture a photograph of an aesthetically pleasing scene.

Upon reflection, this result makes sense. The people who live in close proximity to an urban park are more likely to use that space as their “backyard” or an escape from their urban surrounding—this is the case at Rittenhouse Square and Jamison Square.

Despite Washington Square and Civic Centers’ similarity in lower population density however, Civic Center is a much more popular park than Washington Square. Further analysis suggests that this is because Civic Center hosts many of the Denver area’s premier events. Washington Square, however, only hosts a few events each year, leaving it largely empty most of the day and year. Thus, I believe that the number of planned events needs to be increased in Washington Square to keep the park utilized until a healthy passive activity level is created from additional residential development.

This type of research and findings can be helpful to landscape architects and planners in two major ways. First, studies like these show that civic spaces located in low-density neighborhoods may need to have more planned events in order to maintain a healthy level of activity. Maintaining a high level of activity often decreases the possibility of crime and positively contributes to the public’s perception of that civic space. Secondly, social media can track how successful changes to the design of the civic space are or identify its failings in real time. For example, the addition of hardscape to the mostly grassy Washington Park could offer a greater degree of flexibility of events in the park and result in more activities.

The differences between these two groups of civic spaces were again highlighted in a textual analysis. For this analysis, word clouds were created from all the Twitter and Instagram posts’ caption text of each civic space. Then, the words were separated into three categories, “Activities,” “Features,” and “Descriptors.”

Washington Square and Civic Centers’ caption text more frequently describe the activities occurring in those spaces, as noted by the bubble size in the diagram above. In contrast, Jamison Square’s “Features” bubble is largest for that civic space. Examples from that bubble indicate people spending time eating at the café or looking at clouds—relaxing activities. Rittenhouse Square’s largest bubble is the “Descriptors” category, indicating people are taking the time to relax and survey their surroundings.

The solution derived from this analysis is that Washington Square needs bold, unique, and aesthetic new features in the park to create an identity that park users will remember and want to visit. Ideally, this solution would increase the size of Washington Square’s “Features” and “Descriptors” bubbles if this analysis were performed again after improvements have been made to the park.

(Related Article: How Twitter and Social Media Enhanced My Experience at #ASLA2013)

This research demonstrates that a social media-based analysis can inform designers and planners of the ways in which people use and perceive civic spaces. It is not intended as a process to replace traditional methods of site analysis, but instead as a supplement that can save those professionals time and money from lengthy observation studies and traveling to sites. This information can be utilized in the creation of a design and planning agenda for redeveloping an underperforming civic space.

Images © Mitchel Loring, Photographs from Instagram by @_tbo and @elizazalea.