Author: Kristin Faurest

Fostering the Future

Low-maintenance is a sought-after quality in landscapes — as well as in architecture, vehicles, pets, hairstyles, flooring, the personalities of prospective mates, and pretty much everything else. We use the word maintenance to connote a necessary evil we prefer to minimize, defer, or avoid. We’d all like to have a kitchen floor that doesn’t require waxing or a dog that doesn’t shed, but why must we take a dim view of the idea that a landscape needs our ongoing attention?

Consciously or not, we denigrate the idea of the work of upkeep and those who perform it. The landscape architecture community isn’t unaware of the problem that we neglect and deride the idea of maintenance. In fact, many articulate and thoughtful voices in the profession have expressed that it’s time to evolve in how we honor the ongoing care of our designed and built spaces.

Picking up the title of landscape architect over landscape gardener in the 19th century “helped legitimize the field at the moment of its definition, but that social standing came at the cost of imposing technical, aesthetic, and statutory boundaries that constrain landscape architecture even today,” wrote Brian Davis and Thomas Oles in Places Journal in an essay suggesting the need to reinvent a discipline hemmed in by its own mission. “The new landscape science will also give space at the table to related practices that are fundamentally important but often ignored or denigrated. Maintenance workers, tree pruners, landscapers, and heavy machine operators should be seen not as imperfect executors of design intent, but rather as collaborators in the process of making and studying landscapes.”

Michael Van Valkenburgh voiced similar sentiment in another essay, noting that “no matter how skilled and artistically inclined horticultural workers are (and they are often extremely talented), they are generally perceived as déclassé, left out of design discussions, and poorly paid…The old name for horticultural worker was gardener, a word that connoted a great deal more dignity in the preindustrial world. Perhaps now with the green movement, the local food movement, and the promotion of urban farming, gardening will be honored more. It needs to be.”

Nanzen-ji temple garden in Kyoto, maintained by Ueyakato Landscape Ltd. Photo courtesy of Nanzen-ji.

Does language matter? Is the root of doing it wrong that we’re using the wrong words?

The world is a great book, as the expression goes, and it’s always worth turning the page to see how familiar problems get different treatment in other cultures. Here at the Portland Japanese Garden’s Training Center, we work regularly with visiting Japanese garden masters who come from a centuries-long legacy of the approach to caring for gardens. There’s a marked difference between Japan and most western cultures in terms of how a landscape is treated over time. It’s the practice that what one of them, Tomoki Kato, a faculty member at the Kyoto University of Art and Design and the eighth generation head of Ueyakato Landscape specifically calls fostering. The word doesn’t connote keeping problems at bay or at best keeping the current level of quality – it’s about encouraging, developing, strengthening, helping the landscape along to be the best possible version of itself – whether it’s a historic garden, a public park, or a contemporary private green space. Kato and his garden artisans have visited us on many occasions, including coming to teach at our Waza to Kokoro: Hands and Heart professional-level seminar since its inception in 2016. He’s fond of saying that it takes 200 years to become a Japanese garden craftsman, a trade that encompasses designing, building, and fostering gardens as a single, self-contained task. In the absence of a medical science that permits such human longevity, 200 years means absorbing the tradition of those who came before you and being an integral part of something of continuity that came before and will outlast you.

Tomoki Kato, Ph.D., teaching participants at the Portland Japanese Garden’s hands-on training seminar in Japanese garden arts. Photo by Jonathan Ley.

The beauty in that idea is that it’s not just the gardens, but also the people who care for them that are fostered. In a Chicago keynote lecture, Kato spoke about his family’s legacy of caring for gardens in and around Kyoto since the company’s founding in 1848. He explained that his guiding principle is that a garden should be 40% construction and 60% fostering because the design and construction of a garden are its birth and the rest of its years its life.

“A garden’s life is much longer than a human life. When a garden is born, we devote so much manpower, materials and money, and pour passion into the garden,” he said, showing a timeline of the abbot’s garden created in 1630 at Nanzen-ji, a Kyoto temple garden under the care of his Kyoto-based firm. “Sometimes, the amount of devotion and passion we poured into the garden and received from the garden’s birth is all forgotten and we just do simple maintenance work to keep present conditions. We forget the passion we once had for the garden. Thus, I always tell my workers to pour care, passion and love continuously into the garden as though it is the birth – even if the work is just the process of simple daily maintenance. Having this spirit and mindset, the routinely done maintenance work changes into fostering.”

The abbot’s garden at Nanzen-ji temple, Kyoto. Photo by Kristin Faurest.

Fostering as a practice has a lovely connotation that changes the way we look at the life of a landscape. Our own Garden Curator, Sadafumi Uchiyama, is a traditionally-trained Japanese gardener and American-trained landscape architect who sometimes calls maintenance “incremental construction” – wording that also adds a weight and dignity missing in the current terminology and suggests upward trajectory instead of status quo. The garden creator in the role of fosterer isn’t absent from our own tradition, either; Beatrix Farrand, for example, followed a very similar tradition to Kato’s philosophy, spending years nurturing what she created.

Changing the language we use may sound trivial in the context of the mad tangle of economic, political, and social factors that feed into how a green space is cared for after its birth. But using the right words can change how we think and do. If we use banal and pejorative terms to describe something in theory, it’s unlikely to exceed that level in practice. Finding idealistic language that pushes us to aspire to a higher standard could be the first step on the right road.

—

Lead Image: A color-saturated autumn at Murin-an, a Kyoto garden maintained by Ueyakato Landscape Ltd. Photo courtesy of Ueyakato.

Sources:

Tomoki Kato, Ph.D. “The Spirit of Kyoto Garden Craftsman.” Keynote delivered at the 2014 North American Japanese Garden Association conference, Chicago, 2014.

Brian Davis and Thomas Oles. “From Architecture to Landscape: The Case for a New Landscape Science.” Places Journal, October 2014. Accessed 23 Oct 2018. https://doi.org/10.22269/141013

Michael Van Valkenburgh, FASLA, with William S. Saunders. “Landscapes Over Time.” Landscape Architecture Magazine, March 2013.

The Divinity of Detail: Lessons from the Japanese Garden

The phrase “God is in the details” is, with uncertainty, attributed to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. But whether it came from the Modernist great or someone else, there is something about the play of detail in the creative process that transcends time and geography.

Detail occupies a particularly complex and nuanced role in the Japanese garden. The Japanese gardener’s planning process is embedded in the details – working up from the individual elements, rather than from a top-down master plan. A layout and sketches inform and help guide the process, but factors such as the available choice of materials can cause a change in the design. It can happen that the directionality of one particular boulder or composition of boulders, or the form of a single tree, becomes the focal point — and by that, the consideration that drives the design.

At the Portland Japanese Garden’s Training Center, we teach the techniques of the Japanese garden to landscape practitioners from outside Japan. Our method blends learning approaches both Eastern and Western, and we enrich lessons in traditional practices with cultural context and contemporary relevance. Studying the Japanese garden as an art form can lead to a deeper understanding of universal fundamentals of design such as balance, the use of empty space, and the impact of detail. It can help make connections across other forms and traditions, and the relationship of detail to the creative process. And it can make us see our own cultural forms anew, because some ideas that might seem deeply, entirely Japanese have resonant counterparts in Western culture:

A fine detail surrounded by blank space in the Portland Japanese Garden. Photo by Tony Small.

Give focus to a detail by making space to hone in on a single essential point. The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson ascribed the impact of a photographic image to the tiny details captured at just the decisive moment, saying that “it is by economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression.” Miles Davis echoed that sentiment a bit more tersely with: “I always listen to what I can leave out.” In a Japanese garden, the empty space around a design detail can give it greater impact and meaning. A tiny recessed decorative motif at the end of a clay plaster wall, a path laid out in all natural materials except for one repurposed piece of carved stone, or even an ephemeral detail like freshly-fallen bright-red maple leaves in a stone basin – all are made more striking by the negative space giving them room to breathe.

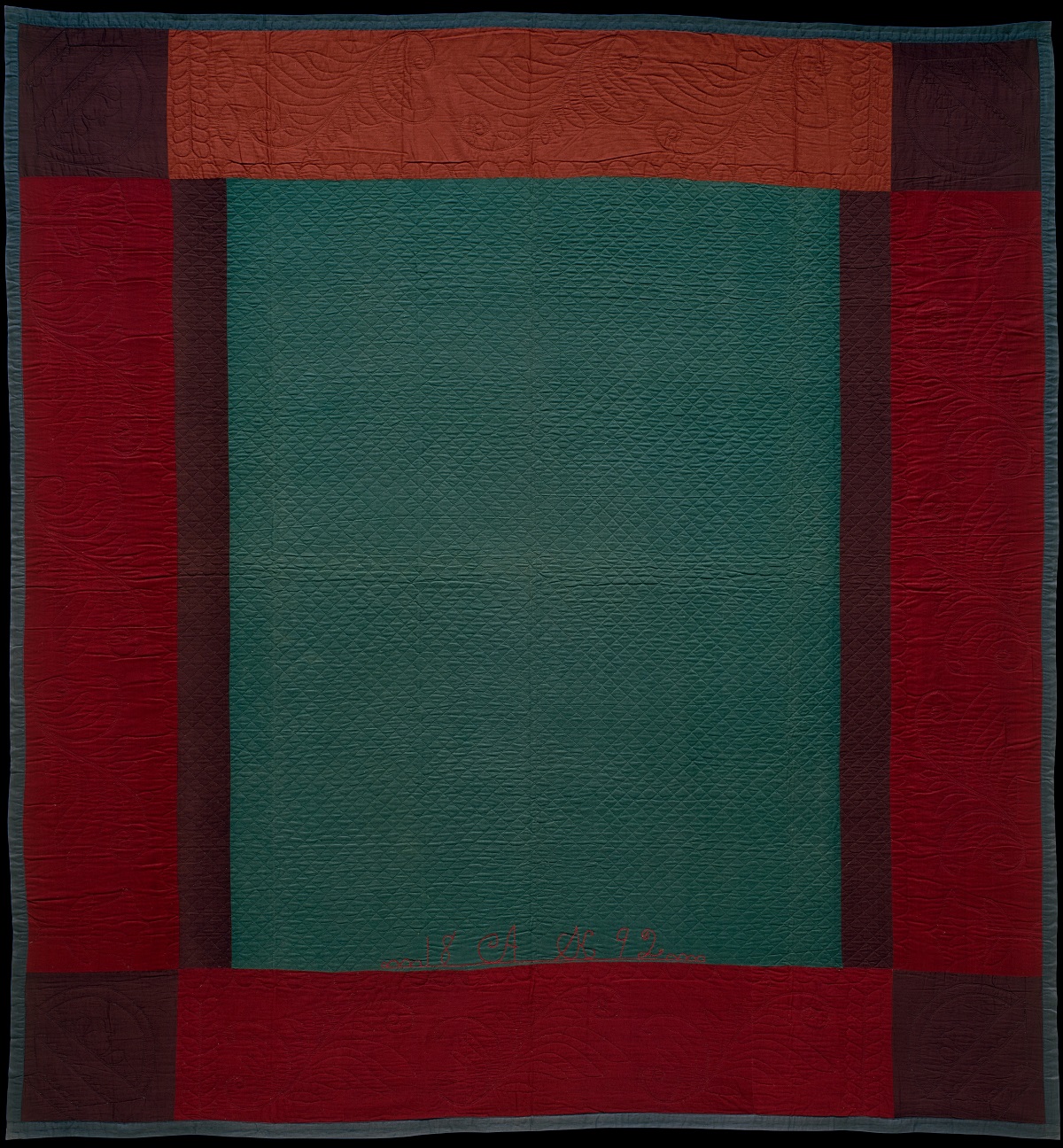

An Amish quilt made in Lancaster County, Pa., dating from 1892 and in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Creative commons license. Accessed on July 2, 2018 at https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/13891

Limitations can inspire excellence in detail. Japanese garden expert, designer and author Marc P. Keane noted in his most recent book that “rather than design everything from the start, some parts of the garden will be created bit by bit as circumstances require with materials that happen to be on hand at the time. The result is a complex quilt that is impossible to achieve in any other way.” In other words, the garden’s design can unfold according to availability of just the right materials for the site, a result that might be quite different from what would result from following a master plan. The reference to quilts lends itself well. Early Amish quilt makers were restricted by religious and cultural custom to using cloth in modest, subdued shades of brown, blue, rust or black. They responded skillfully by creating patterns of up to 14 stitches per inch in intricate and flowing decorative designs inspired by the elements of the natural world that they loved. Swirling feathers, curves, and grids serve as a subtle representation of the resourcefulness and individual spirits of their makers — easily missed if one doesn’t know, or take the effort, to look for them. Flashy colors in striking patterns might be more eye-catching, just as a garden path of expensive and rare stone might loudly call attention to its owner’s power. But a garden path created of humble small stones – by, for example, the arare koboshi (fallen hailstones) style, involves selecting just the right river stones and fitting them together like a linear puzzle in just the right way. It speaks of a patron who expresses taste and wealth softly. The materials are humble, the artisan’s attention to detail is formidable, and the eye that recognizes the level of craftsmanship is rewarded.

The small detail of a charcoal drain in a private Kyoto garden represents a perfect integrity of materials, composition, form, and function, a simple solution from what is readily available. Photo by Kristin Faurest.

A true master of detail takes care of the invisible, too. No one is sure why, but the Parthenon’s sculptural friezes included an immense amount of tiny sculptural details that, even with their original vivid colors, were, in their original siting, in some extremely hard-to-see places. In Japanese gardens, the finest details are sometimes in the most obscure places. Keane cites the sheaths of fine cypress shingles or thin plates of bark on a roof – well out of the sightline of a visitor on the ground – as an example of taking care with nearly-invisible details. So too are certain styles of bamboo fence, in which each node of each bamboo stalk has to be precisely cut with a notch to allow the neighboring bamboo piece’s node to fit. The technique itself is invisible to the viewer’s eye, which only sees a perfectly aligned and joined row of bamboo stalks. A work is only as good as its tiniest, least visible detail.

A Kennin-ji style of bamboo fence, created by craftsmen from Miki Bamboo of Kyoto in collaboration with the Portland Japanese Garden’s gardening staff, embodies skill in hidden detail. Photo by Bruce Forster.

A well-chosen detail can be the most evocative voice. A gifted designer can include details in a garden from natural and manmade materials to suggest the place’s story, subtly depicting gentle human traces left on the landscape over time. Here at the Portland Japanese Garden’s Antique Gate, for example, repurposed roof shingles embedded in the ground in a seemingly random pattern around the gate suggest the passage of time that it took them to naturally fall from the roof and form scattered patterns on the ground. It also reflects the Japanese practice of mitate-mono, seeing an object anew. The same philosophy can be seen in the details of the High Line in New York, where Piet Oudolf paired native plants with hardscaping elements to quietly suggest the feeling of walking down a rail line abandoned by humans and gradually reclaimed by wild nature – right in the middle of the noise of 8.5 million people.

An entire history of a place can be fleetingly but powerfully referenced by a design detail. It’s a beautiful and sophisticated means of telling a landscape’s story.

Sometime after the phrase “God is in the details” was coined, its counterpart, “the devil is in the details” also became common currency. It’s common sense that failure to pay attention to small things can doom the large things in any project. But it’s far more captivating to believe that in paying devoted attention to detail, there is something that elevates us – and, by extension — the works that we make.

Sources referenced:

Cartier-Bresson, Henri. The Decisive Moment. Simon and Schuster, 1952.

Keane, Marc P. Japanese Garden Notes: A Visual Guide to Elements and Design. Stone Bridge Press, 2017.

Smucker, Janneken. Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Tingen, Paul. Miles Beyond: Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991. Billboard Books, 2001.

—

LEAD IMAGE: Even an ephemeral garden detail not necessarily intended by the designer can give voice to a season or mood. Photo by Kristin Faurest.

Listening to Nature – and Each Other

Landscape architects — like many designers — regularly engage with what are commonly called ‘wicked’ problems. Wicked not in the sense of evil, but in the other definition: a problem that is difficult or thorny due to incomplete, contradictory, and constantly changing information, and requirements that are hard to recognize. Urban overcrowding, climate change, economic disparity, and inequity in green space access – wicked problems, all. As designers, we hope and expect to not only be able to conquer wicked problems, but also manage to create works of sublime beauty that are a pleasure for people to occupy and use.

Ian McHarg’s influential 1969 Design With Nature focused attention on the then relatively-new idea that we shape the earth best when we plan and design with careful regard to both the ecology and the character of the landscape. In Japan, meanwhile, the importance of listening to and taking lessons from nature had been in practice as early as the eleventh century, as can be gleaned from the medieval garden treatise Sakuteiki.

Listening to nature now also includes perceiving the signs of climate change. This was an important component of the Portland (Ore.) Japanese Garden’s 2017 expansion project, for which the Tokyo architecture firm of Kengo Kuma and Associates created a LEED-certified complex of buildings inspired by traditional Japanese architecture. The Garden sits nestled in the West Hills of Portland, overlooking the city and providing a tranquil urban oasis for locals and travelers alike. Designed in 1963, it encompasses 12 acres with eight separate garden styles, and includes an authentic Japanese tea house, meandering streams, intimate walkways, and a spectacular view of Mt. Hood. The new Cultural Village — a complex of buildings and courtyard with a modern interpretation of Japanese architectural tradition — is a place where visitors can immerse themselves in a variety of programs in traditional Japanese arts. It is indeed a thing of sublime beauty. But it also represents design in collaboration with nature: large sliding window walls allow access to light and fresh air, living rooftops made of porous thin ceramic tiles decrease runoff and contribute to the buildings’ climate control, and geothermal-powered hydronic radiant heating minimizes the need for energy to heat and cool the buildings.

The top of Sadafumi Uchiyama’s dry creekbed, which channels runoff from the Portland Japanese Garden to a concealed holding tank. Photo courtesy of the Portland Japanese Garden.

Garden visitors arrive at the Welcome Center at the bottom of a steep hill, and ascend the hill either on foot or by shuttle to reach the Cultural Village before continuing to the five traditional gardens. The former includes a small urban courtyard garden, a castle wall constructed by a fifteenth generation Japanese stonemason, and a bonsai collection. The expansion project also transformed the hillside into an essential part of visitors’ experience of entering the Garden. Work on the hillside included removal of invasive species and native plant restoration, but its most significant transformation focused on water management. Garden Curator, landscape architect, and fourth-generation Japanese gardener Sadafumi Uchiyama designed a green infrastructure system rooted in Japanese stone-setting tradition. A stone creek bed runs from the top of the hillside all the way down to the parking lot, channeling and filtering runoff down the hill while serving as a striking linear element visually connecting the upper and lower Garden areas. Water goes into a nearly 27,000 gallon holding tank under the parking lot and is slowly released into the city’s combined storm water and sewer system. To the Garden’s nearly half-million annual visitors, the creek bed is an aesthetically pleasing design element of the Garden. But it’s also a critical piece of infrastructure. Projections show that annual precipitation will increase in Oregon mostly during the cold weather months, and future precipitation patterns are also estimated to be more unpredictable and extreme than in the past. The Willamette Valley’s typically dry summers and wet fall, winter and early spring months will likely become even more so, meaning summer water scarcity and significantly higher levels of runoff the rest of the year will become the new normal.

The creekbed is part of visitors’ experience entering the garden from the Welcome Center below. Photo courtesy of the Portland Japanese Garden.

If Uchiyama was calling upon centuries of Japanese gardening techniques and a tradition of living as one with nature to address a water management problem in 21st century Portland, the current flows the other direction as well. In 2014, a Japanese delegation came to study Portland’s green infrastructure system with the hopes of advocating for the development of similar green infrastructure policy back in Japan. Interest in ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction has increased dramatically in Japan since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

What does all the above teach us?

We need not just to listen to nature, but to each other. Good ideas flow across national borders and through the ages. For every wicked new problem designers have to wrestle with, there is someplace in the world where someone has had to deal with that same problem for a long time — and out of necessity found resourceful and even beautiful ways to cope with it. Think about thousand-year-old earth-sheltered houses in China, passive solar heating ideas used 900 years ago by the Pueblo Indians, and modular building techniques used in Japan for half a millennium. India has an entire vocabulary of different structures for capturing and storing precious rainwater going back centuries, and scientists recently rediscovered a 700 year old African technique for soil enrichment unmatched by any modern technology.

The Kamo River in Kyoto, once polluted, now serves the classic blue/green infrastructure roles of vital urban wildlife habitat, recreational destination, and green transport corridor. The river features large concrete stepping stones that enable pedestrian crossing while also referencing historic garden tradition. Photo by Kristin Faurest

For some disciplines, there’s a more or less agreed-upon, standard canon of required, fundamental works of literature. This is not the case in landscape architecture. Ask ten landscape architects to name their essential readings and you’ll have ten different lists with minor overlap — there are myriad worthy works both classic and new. But it’s entirely possible that in the 21st century, for a landscape architect, the most essential textbook is a well-worn passport.

For details on Portland Japanese Garden’s International Japanese Garden Training Center programs, go to: japanesegarden.org/thecenter

Sources cited:

- Fukuoka, Takanori, and Sadahisa Kato. “Toward the Implementation of Green Infrastructure in Japan Through the Examination of City of Portland’s Green Infrastructure Projects.” Accessed May 16, 2018, at https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jila/78/5/78_777/_pdf/-char/en

- Japan Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation Bureau. Ecosystem-based Disaster Risk Reduction in Japan: A Handbook for Practitioners. 2016.

- McHarg, Ian. Design With Nature. Wiley, 1969.

- Oregon Climate Change Research Institute. The Third Oregon Climate Assessment Report, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018, at: http://www.occri.net/media/1042/ocar3_final_125_web.pdf

- Portland Japanese Garden blog: https://japanesegarden.org/2016/04/12/responsibly-growing-green-garden/

- Interview with Prof. Arno Suzuki, Kyoto University, May 16, 2018.

- Taylor, John S. Commonsense Architecture. W.W. Norton, 1983.