Author: Stephanie Swindle Thomas

Baseball, the Olympics, and Jekyll Island: Geodesign Students Address Real World Scenarios in the Virtual Classroom

Classes are back in session on campuses across the country, including virtual ones. Penn State’s Geodesign program, an online professional master’s degree program offered through Penn State World Campus, provides students the opportunity to have collaborative experiences with design professionals online and to become the missing piece of the sustainability puzzle. Rather than being immersed in one area of design, students study the ripple effects of major issues facing their studio projects and the future of design.

“The one commonality our students have coming into the program is that they have never done Geodesign,” noted James Sipes, faculty member for the Penn State geodesign online master’s program and founding principal of Sand County Studios. “Instead, they all have different skill sets and strengths that they bring to working collaboratively on their projects.”

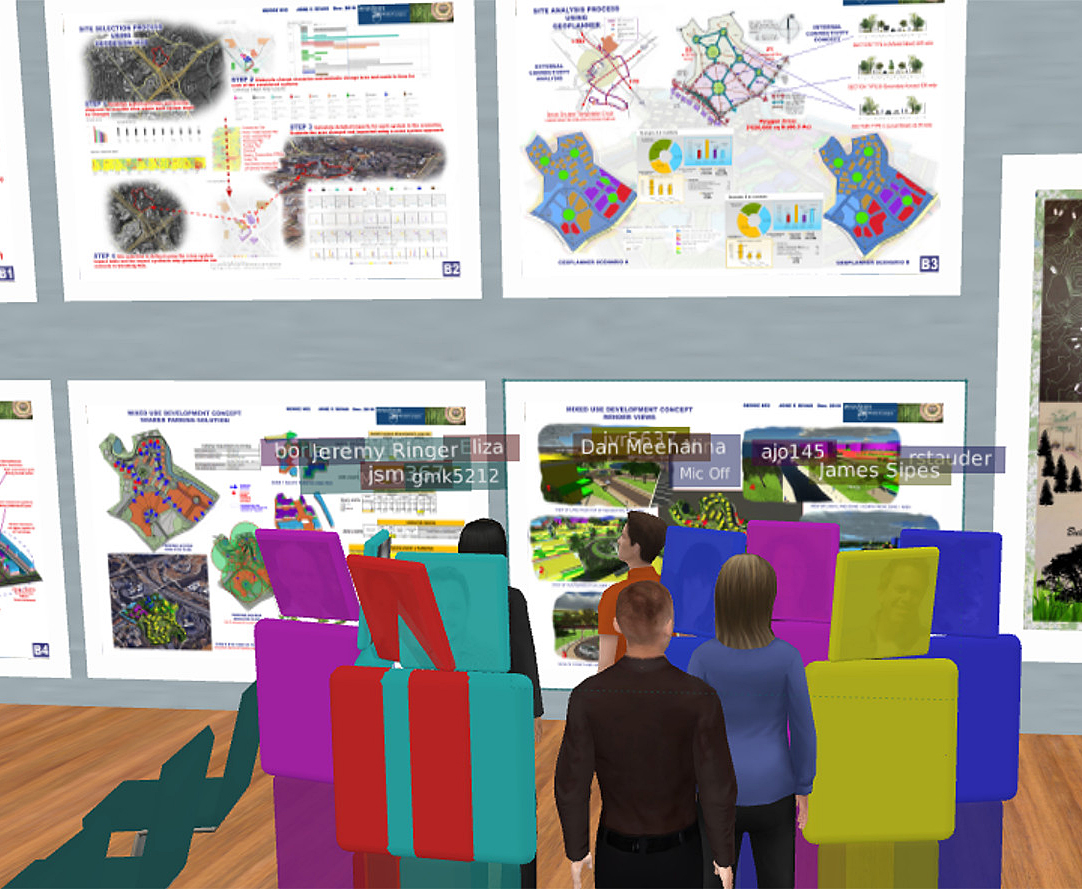

Bringing geographically dispersed students and reviewers together is the role of the TERF virtual studio. Through an easy web-based interface everyone can be present and engage in a spatial context that allows a full display of all the students’ work.

Many Geodesign students are already working in fields related to planning, GIS, construction, insurance, real estate, and related professions across the globe. Sipes’ courses bring them together for sixteen sessions using collaborative software, such as TERF, ZOOM, Geoplanner, and CityEngine, to communicate, design, and think critically about resiliency issues such as growth pressures and sea level rise.

“The tough part of the studios is that we are asking them to do two difficult things – master a set of digitals tools new to most people and customize them to address their project goals,” noted Sipes.

Last semester’s course provided a unique experience for the students – to prepare a potential summer Olympics bid for Portland, Oregon. Students chose to design different venues, including the Olympic Village and sports facilities. Stakeholders participated in design reviews via a virtual studio, called TERF, and were impressed with the quality and articulation of the students’ designs. Feedback from Sipes, other students, and members of the Portland team helped students prepare for their future professional projects.

“That is what is great about this course,” said Ana Hampshire, a part-time student in the Master of Professional Studies in Geodesign program, who also works in the construction department of a commercial real estate development company in Houston, Texas. “It opens your mind and prepares you for different realities and circumstances.”

Geoplanner (right) provides dynamic, real-time readouts showing how well design scenarios address the desired criteria. City Engine (left) allows the design to be explored and represented in realistic 3-D visualization.

Sipes, having worked on the retrofitting of the Atlanta Olympics venues, lends his professional expertise to the courses he teaches. His previous studio course drilled down to designing the area around one sports venue, the Atlanta Braves baseball stadium. This semester he has lined up another unique project. The students will address the ecological challenges facing Jekyll Island, a 6,000-acre barrier island off the coast of Georgia.

Jekyll Island was once an exclusive vacation spot for wealthy Americans, including the Rockefellers and J.P. Morgan. During World War II, the government closed their beach club to prevent it from becoming an enemy target. The state of Georgia purchased the island in the 1950s and has preserved 65 percent of it, leaving only 35 percent for development. Due to Jekyll Island’s unique history, a robust set of available data, and the similarity of environmental challenges facing coastal regions in the United States, students will address scenarios ranging from sustainable development and conservation to disaster relief.

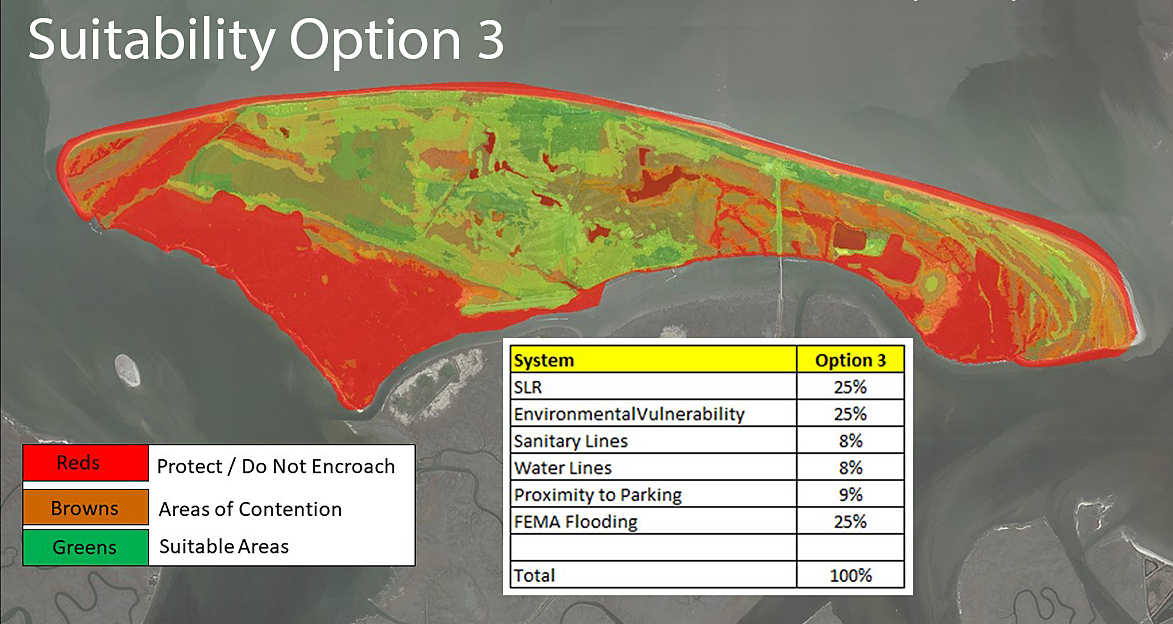

The geodesign process emphasizes what stakeholders value. In this option (#3), stakeholder values related to sea level rise and environmental vulnerability are given higher weight; the resulting map outlines where it is suitable and not suitable to accommodate growth. Multiple options can be modeled and explored based on a different set of stakeholder values.

“I think geodesign is the solution to wicked problems. We’re giving our students the tools for resiliency design, but, more importantly, we are teaching them how to think. Good ideas require complex, creative problem-solving skills in order to arrive at smart, comprehensive decisions,” said Sipes. “If we’re going to change the world, this is what we’ve got to do. Everything is interconnected.”

For more information about Penn State’s Geodesign program, visit the website: https://geodesign.psu.edu/.