Author: The Field by ASLA

The Role of Landscape Architects in Roadway Design Projects

Historic Colorado bridge at US-24 over the Arkansas River / image: Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Region 5

State Departments of Transportation (DOTs) employ landscape architects who often serve as the aesthetic “eye” for transportation construction projects, selecting colors and textures, developing seed mixes, and providing other expertise to help projects blend into the surrounding context. Many DOT landscape architects conduct visual resource clearances through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process with the end goal of producing visual mitigation measures (see Visual Resources in the Practice of Landscape Architecture for more on this). This article is the first in a series that aims to outline gaps in visual mitigation guidance as well as provide opportunities and solutions to fill these gaps. The first gap that will be addressed is the disconnect between visual mitigation and the timing of project delivery. This article will outline a path forward to clarifying the landscape architect’s role in the NEPA process.

The root issue is that the timing of visual resource studies in the environmental process often restricts landscape architects to selecting aesthetic treatments or landscaping that will not drastically alter design, such as selecting colors, textures, materials, and seed mixes. There is a common misconception that landscape architects and landscapers are synonymous, and that because landscaping typically comes at the end of a construction project, landscape architects become involved at that phase. Minnesota DOT mentions that “early involvement of landscape architects can facilitate climate resiliency, thoughtful preservation and enhancement of environmental and community assets, human comfort, and visually pleasing transportation experiences,” but their Visual Quality Management (VQM) typically occurs at around 30 percent design. With the exception of high profile projects, DOT landscape architects’ involvement often occurs well into design.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2023 there were 24,700 landscape architects in the United States but fewer than 2 percent of them worked for state agencies. State government agencies employ more than ten times the number of engineers as landscape architects nationwide. Like professional engineers, landscape architects must be licensed by the state. The Landscape Architect Registration Examination (LARE) is the professional licensing exam for the profession. The sections covered on the exam include Inventory and Analysis, Planning and Design, Construction Documentation and Administration, and Grading, Drainage and Stormwater Management. Because landscape architects are seldom involved early enough in design, however, they are not always given the opportunities to apply these skills and show that they can do more than stamp a planting plan. Since many DOTs only hire a small number of landscape architects and don’t leverage the training and credentials they bring to the table, there is a missed opportunity to apply their interdisciplinary expertise.

A Public Roads article from 2000 titled “Roadways and The Land: The Landscape Architect’s Role” outlines how the landscape architects’ function shifted away from being a key player in design in the twentieth century due “to the decline of collaborative highway design in favor of urgent, rapid construction of military highways, which provided mass employment and met national security needs.” National standards developed after WWII with the advent of America’s interstate highway system left little room for context sensitive design or flexibility. Ellen Oettinger White, a professor of landscape architecture at the State University of New York School of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), interviewed over 40 DOT staff members and found that “Landscape architects in transportation settings who felt they had a voice or an influence over what the highway engineers were doing were the ones who had a very long tenure at these public agencies. They spent decades proving their expertise to their colleagues and building relationships, while engineers were granted that assumption of expertise the moment they enter the room.” In Ellen’s 2022 presentation at the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) Innovation and Leadership Symposium titled “Roadsides and the Nature of Power in Landscape Architecture,” she emphasizes the root of this issue: landscape architects need to take back their power at DOTs.

Fortunately there are plenty of case studies in which DOT landscape architects are taking innovative steps to educate staff on what landscape architects do and shift their involvement. Virginia DOT released a memorandum describing the role of landscape architects and how it fits into project development. It could be used as a template for landscape architects at other DOTs to do something similar. In recent years, many DOTs and national research organizations have been prioritizing research on understudied landscape architecture-related topics like pollinator habitat conservation and wildfire mitigation in roadside revegetation. The National Highways Cooperative Research Program (NCHRP) administered by the Transportation Research Board (TRB) and sponsored by State DOTs, AASHTO, and FHWA has been a powerful avenue for research funding. Of course, the end result of these studies is usually guidelines, so it is up to individual DOTs, with the help of landscape architects, to ultimately reflect these guidelines in their project delivery manuals. It is the responsibility of landscape architects to not only incorporate our skills into projects but to educate our colleagues about our profession to change the way we do projects. That is an immense task when landscape architects are faced with administrative hurdles, but a small change can have far reaching impacts once embedded in standard processes.

—

About the Author:

Liia Koiv-Haus, ASLA, AICP, is a Landscape Specialist for the Colorado Department of Transportation. She also serves as an officer for ASLA’s Landscape—Land Use Planning Professional Practice Network (PPN).

Resilient Landscapes: Native Plants and Local Solutions

Today, landscape architects and designers have access to an unprecedented variety of plant species and hardscape materials. Thanks to modern advances in distribution, cutting-edge greenhouse technologies, streamlined inventory systems, and online resources our choices have expanded dramatically, no matter where we practice. However, this abundance can lead to decision fatigue, or conversely, complacency—repeatedly specifying a limited selection of exotic plants or standard materials simply out of habit and reconfiguring them for each site. Corporate or institutional clients and homeowners face similar challenges, turning to landscape architects for guidance not only for achieving aesthetic clarity but also to distill the options, reduce unnecessary complexity, and, crucially, design in a way that actively supports resilience and biodiversity, and reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Though often seen as ‘green,’ the landscape industry isn’t always as sustainable as it appears. Digital tools such as the Pathfinder app by Climate Positive Design help designers make more ecologically responsible choices by offering a ‘use this, not that’ approach, for both materials and plants. The tool also quantifies a project’s environmental impact, including carbon sequestration from plants, allowing users to measure the benefits of sustainable decision making and to test different solutions from a climate positive perspective.

Research has shown that about 70 percent of a site’s plants must be regionally native to maintain healthy food webs. If the proportion of non-native plants exceeds 30 percent, the food web begins to break down, leading to decreased reproduction and survival rates in species reliant on insects for food. These are the species offering ecosystems services such as pest control, soil enhancement, and pollination. A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that reliance on non-native plants can disrupt ecosystem functions, making native plant communities more resource hungry, shallower rooted, and less dependent on mycorrhizal associations. These shifts can significantly affect nutrient cycling, carbon storage, and water usage. To truly future-proof landscapes, we must prioritize sourcing healthy, field-grown native plants and master when to specify and how to maintain them. (Growing native plants at home enhances our understanding of their needs. Yet many landscape designers I know grow natives personally but specify exotics in their work.)

Landscape architects, designers, contractors and homeowners all share the responsibility of supporting native plant growers by leveraging their expertise, specifying their plants, and collaborating with local brokers who source directly from these growers. Supporting native and local growers also means understanding the significant up-front investment required by growers, as shrubs typically take 2 to 5 years and trees 5 to 10 years or more to reach a market-ready size. Contract growing is a valuable way to show your commitment to these businesses, ensuring the availability of specific plants. Open an idea exchange with your local grower by getting to know them and communicating your experience with natives—it will be mutually beneficial.

In projects where specifying particular businesses is restricted, such as municipal work, the Sustainable SITES Rating System provides guidance. SITES encourages the use of native and locally adapted plants, emphasizing plant performance standards, genetic diversity, and the importance of sourcing from regional growers. By specifying locally sourced native plants, landscape architects can support native growers while adhering to procurement guidelines and aligning with sustainability goals like reducing transportation emissions and enhancing biodiversity.

It’s important to note that native plant growers operate largely outside the industrialized distribution systems which often centralize growing operations in regions that may not match destination ecosystems. As a result, industrial-scale growers or distributors may oversimplify native plant selection (if they offer them at all), prioritizing species that tolerate long containerization periods, or withstand mass-market transportation, rather than those that support ecosystem resilience and biodiversity. Unlike these large operations, even sizable local native growers often rely on ecological practices such as using local wild seed and manual weed control which are harder to quantify under formal eco-certification programs. This reinforces the need for landscape architects to support local growers directly.

Large distribution networks aren’t inherently negative, but they can limit our plant choices unless we actively realign our buying practices with biodiversity and sustainability goals—ensuring that we prioritize sustainability not just in hardscape materials but in plant selection as well.

While certification programs recommended by organizations promoting green nursery practices can guide specifiers, many regional native plant growers don’t participate in these programs due to the high costs and administrative complexity involved. Similar to local organic farms, local growers often prioritize ecological practices that aren’t easily captured by broad certification standards, which tend to emphasize chemical or energy consumption. For instance, smaller native plant growers commonly collect seed from local wild populations—preserving genetic diversity and regional adaptations—rather than relying on commercially produced seed or cloned starts. They may also propagate plants in-house, favor manual weed control and appropriate mycorrhizal inoculation, and often field-grow plants under natural conditions, reducing energy and water needs and producing more resilient plants. This makes it our responsibility to proactively support local native growers who prioritize sustainability in daily practices.

When selecting plants, remember that a plant chosen for its biodiversity value isn’t just a plant—it’s a connector. As a primary producer, it transfers energy throughout ecosystems, supporting life both above and below ground, even if today it’s just a symbol on a digital plan. Once installed, a plant can help rebuild entire ecosystems. But we must carefully consider ecological niches and choose appropriate species when specifying natives. For example, native grasses like Bouteloua or Panicum can provide erosion control and bioremediation, while seasonal wildflowers such as Asclepias (milkweed) could help restore Monarch butterfly populations and decompact soil. Carefully chosen shrubs, such as Ceanothus (pictured above), offer multiple benefits—aesthetic beauty, low maintenance, nitrogen fixation to enhance soil, and climate-appropriate water use—while also supporting struggling lepidoptera species. By selecting plants for specific goals, such as supporting bird or butterfly species, we can achieve broader ecosystem benefits without sacrificing aesthetics.

The next time you review a planting plan, think of each plant as an energetic connector—providing home, food, shade, beauty, even medicine. Remember a key rule of ecology: nature’s resilience comes from functional redundancy. Every species plays a role, even if we don’t fully understand it yet. Biological insurance means nature doubles up on ecosystem services, allowing ecosystems to fail safely and recover—the essence of resilience. By diversifying your plant palette and supporting local native plant growers, you create a more resilient, future-proof landscape. Fostering both ecological and economic resilience ensures our landscapes—and the communities they support—will thrive together.

—

Resources:

- Decarbonizing Specifications: A Guide for Landscape Architects, Specifiers, and Industry Partners, ASLA

- “Naturalized species drive functional trait shifts in plant communities,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Pathfinder tool, Climate Positive Design

- “Nonnative plants reduce population growth of an insectivorous bird,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- “Supply of Native Seeds Insufficient to Meet the Needs of Current and Future Ecological Restoration Projects,” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

Jodie Cook, ASLA, PLA, SITES AP, is President of Jodie Cook Design in Orange County, California. In addition to landscape architecture, Sustainable SITES consulting, and program management, Jodie teaches The Sustainable Landscape and Native Garden Design at Saddleback College. Her education-based turf removal incentive program, NatureScape, was featured in the ASLA’s Smart Policies for Climate Change exhibition. She is certified in watershed-wise landscape design (WWLP), a Qualified Water Efficient Landscaper (QWEL), ReScape and USGBC Wildfire Defense and Resilient/Regenerative Firescaping certified. Jodie is also on the leadership team for ASLA’s Planting Design Professional Practice Network (PPN).

Lost in Translation: Society’s Mix-Up of ‘Environment’ in Landscape Design

In the fabric of our language, words have different shades of meaning. Each word carries a special sense, reflecting its depth and complexity. However, one word, ‘environment,’ has kind of lost its original meaning, especially when we talk about landscape architecture. People often use it carelessly, and this has watered down its real significance, overshadowing the nuanced understanding that landscape architects want to convey.

At its core, ‘environment’ is not just the background or a general term for our surroundings. It’s a concept that includes the complex relationship between living things and the world around them, stressing how nature and human intervention work together. However, in today’s talk, ‘environment’ has become a catch-all word, casually used to describe anything from city spaces to natural places, often missing the subtleties of landscape architecture.

On the flip side, the word ‘landscape’ carries the idea of intentional design and human involvement. Landscape architecture goes beyond just the basic idea of ‘environment’ and gets into the detailed planning of spaces that make us feel things, promote sustainability, and blend with the natural world. But the way we use ‘environment’ and ‘landscape’ interchangeably blurs the lines between just being surrounded by things and purposeful design.

In this discussion, we need to ask how this simple mix-up in words affects how we see and do landscape architecture. Using ‘environment’ like we do makes people think of the discipline as just a part of environmental science, rather than understanding its unique role in shaping how things look and feel around us.

The mix-up is clear in discussions about building cities. Urban planners and policymakers often talk about the ‘urban environment’ without recognizing the nuanced approach landscape architects bring to the design of city spaces. The city isn’t just a passive ‘environment’ but a purposeful ‘landscape’ that can influence how people act, build communities, and add to the well-being of those living there.

Moreover, using ‘environment’ casually takes away from the importance of sustainability in landscape architecture. Sustainable design isn’t just about being eco-friendly; it’s about making landscapes that last, adjust, and contribute positively to nature. When ‘environment’ becomes a broad and vague word, the urgency of designing sustainable landscapes gets lost in the general talk about saving the environment.

The mix-up doesn’t stop at just words; it affects how landscape architecture is put into action. When we use ‘environment’ like we do, the essence of intentional design gets watered down. Landscape architects aren’t just watching nature happen; they’re creators who mix the built and natural worlds into a seamless and purposeful design. Using ‘environment’ casually ignores the focus on human experience, cultural context, and the artistry of putting spaces together.

The misappropriation of ‘environment’ also has consequences for how landscape architecture fits into collaborations with other disciplines. When ‘environment’ is thrown around without care, the specific contributions of landscape architects often get overlooked. This makes it harder to see landscape architecture as a unique discipline that connects art, science, and taking care of the environment.

To fix this mix-up in words, we need to bring back the richness and clarity of language when we talk about the work of landscape architects. Using ‘landscape’ instead of ‘environment’ is a small but important step in reminding everyone of the discipline’s identity and helping people understand its role in shaping the world around us.

In conclusion, it’s crucial to remember that words matter, especially in landscape architecture. Using ‘environment’ without thinking waters down the intentional and creative aspects of landscape design. If we switch back to using ‘landscape’ more often, we can revive a more accurate appreciation for the discipline, highlighting its role as a dynamic force shaping the spaces we live in, both in looks and experience. It’s time to challenge the mix-up in words and bring back the depth and clarity that language should offer in understanding and celebrating the artistry of landscape architecture.

—

Lucila Silva-Santisteban, MLA, B.ARCH, ASLA, is Colombian-Peruvian landscape architectural and urban designer based in New York City, with 10 years of professional experience in the landscape, architecture, and urban design field, both in her home country of Colombia and in the US. She is currently part of the design team at the NY office of Enea Landscape Architecture located in Brooklyn, NY. As a Project Designer and Coordinator she focuses on creating beautiful and sustainable landscapes on local and international projects drawing from her diverse experience.

Lucila holds a Master’s in Landscape Architecture from the Rhode Island School of Design and a B.Arch. from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá, Colombia. Founder of LAUD Research initiative—a landscape architecture design research-focused exploration—she studies solutions through visualization and mapping in response to social-ecological issues of the landscape caused by climate change and current political-economical models affecting our world.

Through Lines: An Exploration of Connections Via Chicago’s Alleyways

Alleyways are misunderstood. Upon hearing the term, most people are quick to think dirty, dangerous, or dark. While all of these reactions are valid, they undersell the magnificence of alleyways.

Defined as “a narrow passage behind or between buildings,” the designation of an ‘alleyway’ can be ambiguous. For our purposes, we will define an alleyway as a narrow passage bisecting a city block, typically accommodating back of house functions like trash collection, utility routing, and delivery services.

At one point in time, the idea of housing utilities at the back of the house was radical. In Chicago, public sentiment regarding alleyways eventually shifted to a sense of pride. Serving as neighborhood capillaries, they provide physical and social connections for Chicagoans. Simply, alleyways arm Chicagoans with the single, incontestable claim over other large cities: the clean, garbage-free street.

This research topic explores the concept of repurposing alleyway systems as an alternative framework of non-motorized connections, using the City of Chicago as a case study.

Chicago has a sizable disparity in access to non-motorized infrastructure, programming, and recreational facilities, correlating with socioeconomic backgrounds of Chicago’s communities. Alleyways are an unexplored opportunity to close the gap in access, while promoting non-motorized modes of transportation, and increasing green infrastructure within the existing urban fabric.

This research will employ various methods such as interviews, GIS analysis, surveying, immersive experience, and precedent study to understand how alleyways can be adapted.

While research is proposed to analyze existing conditions in the City of Chicago, the methodology will provide research frameworks, engagement mechanisms, and distinctive design interventions for comparable cities. This analysis aims to identify alleyway reconfiguration criteria based on a set of demographic, destination-based, and site-level factors to ensure processes and recommendations can be replicated elsewhere.

A History of Chicago’s Alleyways

Chicago has the most extensive alleyway network in the country, totaling more than 1,900 miles. While alleyways can occur spontaneously, the City of Chicago intentionally planned for alleyways from the beginning. The original town plat of 1830 included eighteen-foot-wide alleyways inscribed into “all 58 blocks.” With the national land survey grid informing Chicago’s block structure, the alleyways of Chicago became continuous, predictable, dependable places for trash collection, utility, commerce, and access. Still today, over 90% of the blocks in Chicago contain alleyways. By providing alleyways within the center of blocks and limiting trash from primary pedestrian thoroughfares, the City of Chicago had managed to limit the spread of rodent borne diseases that plagued other cities like NYC.

In the last several years, the appreciation of alleyways in the City of Chicago has re-emerged, even manifesting into a 2001 City-wide Green Alley initiative to improve and better utilize this essential resource. To this day, more than 300 Green Alleys have been installed throughout the City.

Chicago is known as the alleyway capital of the country, for good reason. Chicago’s initial and continued investment in its alleyways has served as an invaluable precedent for other cities and has paid dividends to every citizen of Chicago’s health and quality of life.

Inventory + Analysis

Geospatial data analysis is utilized in order to understand the potential of Chicago’s existing alleyway network, demographic trends in neighborhoods, and gaps in access. It should be noted that this analysis is rooted in assumptions and quantitative data.

The analysis framework is as follows:

- Existing Infrastructure. Assess where “connected” alleyways exist that run for longer than one mile.

- Understanding Access. Understand demographics and access to existing infrastructure within Chicago neighborhoods.

- Connecting Resources. Identify alleyways longer than 1 mi that directly connect to community resources.

- The Big Picture. Identify neighborhoods experiencing gaps in access with alleyway segments that are continuous for longer than one mile.

Existing Infrastructure

This analysis identifies “connected alleyways” that are naturally occurring in the City today. For the purposes of this analysis, “connected alleyways” are designated as a series of connected routes with entry/exit points within 200 feet of each other. These naturally-occurring alleyways are ripe for retrofit and non-motorized uses.

Understanding Access

A weighted analysis was used to measure the severity of the following demographic and infrastructure conditions within Chicago neighborhoods today:

Social Vulnerability

- Vehicular ownership

- Poverty levels

- Education

- Race + ethnicity

- Disability status

- Exposure to pollutants

- Population density

- Housing unit density

- Walkability

Infrastructure + Access

- Areas more than 0.5 miles away from a neighborhood greenway or protected bike lane

- Areas more than 0.25 miles away from an off-street trail

- Amount of accessible parkland per 1,000 people

- Areas within a 0.25 mile radius of incomplete or missing sidewalk conditions

Connecting Resources

Alleyways running longer than one mile are overlaid in order to identify which alleyways directly connected to the highest number of community destinations. For the purpose of this research, “community destinations” are as follows:

- Public/private schools

- Chicago libraries

- Daycares

- Total jobs

- Bus/transit stops

- CTA rail stations

- Metra stations

- Bus stops

- Divvy stations

- Retail

- Restaurants

- Rec, nature, cultural facilities

- Museums

- Places of worship

- Health center

- Urgent care centers

- Hospitals

- Chicago service centers

- Grocery

- Farmer’s markets

- Community gardens

The Big Picture

Building upon previous steps, the final composite map displays “connected” alleyways

with high frequencies of direct connections to community destinations in areas of social vulnerability. According to these factors, the following community areas have been identified for further research:

Baseline Retrofits

Focus: West Ridge

Located on the North Side of Chicago, West Ridge is a thriving and diverse mix of cultures, with a significant amount of culinary and open space destinations. Today, the community lacks non-motorized connections to route residents to destinations, specifically along Devon Avenue – a key node for Chicago’s Indian, Pakistani, and Jewish communities. The alleyway of study within West Ridge is directly north of Devon Avenue.

West Ridge Intervention Opportunity

Problem

A primary concern of introducing new non-motorized passages within alleyways is establishing crossings where no infrastructure currently exists. This creates conflict points between motorists and non-motorists.

Methodology

While the purpose of this research was context-specific to Chicago’s alleyway system, the research methodology could serve as a framework for similarly designed cities.

Conclusion

The problems of this generation demand innovative policy and creative design, warranting a restructuring of the established models. While affordability, equity, and sustainability issues are complex and globally experienced, solutions lie at the neighborhood and site-specific level. The public realm should be designed for the community, prioritized by governing bodies, and preserved by users in order to create long-lasting social, economic, and environmental benefit within the American fabric.

Comprehensive solutions exist within our current infrastructure—and we need to be audacious enough to seek them. Our cities can be more if we can discover the through line.

If you have any questions about Through Lines: An Exploration of Connections Via Chicago’s Alleyways, please contact tom.martin@smithgroup.com.

—

Originally posted in The Field by Tom Martin, PLA

Tom Martin, PLA, is a landscape architect in SmithGroup’s Chicago office. He has long been curious about the potential of alleyways and other dormant infrastructures and their greater potential. Tom is a past co-chair of ASLA’s Environmental Justice Professional Practice Network (PPN).

Tom Martin, PLA and Caeley Hynes, AICP, recently finished a research project related to alleyways in Chicago, where they explored the potential of adapting them to better serve alternative modes of transportation. While this post summarizes key findings and provides a sampling of our research, the full report can be found here.

LEAD IMAGE: Courtesy of Tom Martin, Caeley Hynes, and SmithGroup

Transit Oriented Districts: Urban Design Experience

Transit Oriented Districts have been helping reinvigorate towns and cities across the United States and Canada. Beyond the limiting definition of Transit Oriented Development (TOD), Transit Oriented Districts (TODts), are typically defined as the whole area within half a mile of a transit station and are seen as desirable choices for development in metropolitan areas to accommodate the concerns surrounding population growth.

TODts are typically characterized by higher development density and a varied mix of land uses, offering sustainable development options to counteract some of the negative effects of urban sprawl, declining urban cores, and congestion sparked by rising populations and mobility. They contain a diverse mix of uses such as housing, employment, institutions, shops, restaurants, and entertainment. These districts aspire to have a strong sense of place, and a diverse set of travel mode choices. TODts are typically designed in conformance with a coherent district plan or zoning overlay that commonly stipulates the type and scale of uses, permitted densities, and related regulatory and recommended items. These districts are usually expected to be organized around the station areas with unified plazas, squares, parks, and streetscapes, and function more like a district than a single development and a project (Ozdil, 2014).

By refocusing design, planning, and transportation practices from cars to other modes of transit, more space can be dedicated to other human purposes, experiences, and city needs. A typical Transit Oriented District favors:

- Focused development (often based on a comfortable walking distance) over sprawl

- A coherent district plan (with a balanced distribution of green and open spaces and streetscapes) rather than a single project

- Pedestrian, cyclists, and mass transit access over the automobile

- Higher density developments, over single story developments

- Compact and shared parking (parking garages and street-edge parking) instead of surface parking lots

- Mixed-used development over conventional zoning and development

The scaffold of the TODt has been adapted to different area types with a diverse set of goals. There may be different factors that lead to variations in their implementation. Population density, available transit options, and the existing infrastructure are consistent factors. Climate, COVID-19, and other concerns, often tied to specific metropolitan areas, also influence how TODts are realized. Thus, it becomes essential to work with typologies that respond to varying densities and needs across a given metropolitan area or urban region. Examples of typologies are Urban Downtown, Urban Neighborhood, Suburban Town Center, Suburban Neighborhood, Neighborhood Transition Zone, and Commuter Town Center (Dittmar et. al., 2004). Additionally, as more of these districts arise, bodies of research and lessons learned influence the next generation of Transit Oriented Districts.

This article is written as a follow-up to the Urban Design Professional Practice Network (PPN)‘s collaborative panel with the Transportation PPN on Transit Oriented Development, which was presented as a webinar in February 2024. The article discusses and reinforces the relevance of a Transit Oriented Districts and offers lessons for pedestrian experience and placemaking to better inform the planning, design, and implementation processes. To get a snapshot of how different cities are implementing them, Urban Design PPN members from different urban regions looked at recent station areas’ TODs or TODts in their communities. They explain their local and regional insights and their experiences.

TOD & TODt Cases & Experiences

TOD: Observations from the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) in NJ/NY

Mode: Rapid Rail System from Jersey City to Midtown Manhattan

Typology: Urban Downtown, Urban Neighborhood

Author: Jenny Zhang, Associate ASLA, AICP Candidate, with WSP USA

The New Jersey and New York area undeniably have significant opportunities for Transit Oriented Development (TOD) projects. I was most attracted to those smaller-scale interventions that contribute to the placemaking of the downtown centers and urban neighborhoods along the transit lines. As a daily public transit user who commutes from Jersey City in New Jersey to Midtown Manhattan, I am fortunate to witness several placemaking projects along my commute on PATH.

My commute journey starts with Newark Avenue in Jersey City, a 0.2-mile pedestrian mall connecting to the Grove St PATH station. This street underwent a conversion into a pedestrian mall a few years ago, and the planters, benches, safety bollards, and string lights significantly enhanced the pedestrian experience. On sunny days, the colorful umbrellas, tables, and chairs from the restaurants along Newark Ave make the street more vibrant.

The density and scale of the built environment change significantly when I arrive at the 33rd St PATH station in Midtown Manhattan. The scale of four-story buildings on the Newark Ave pedestrian mall suddenly increases to skyscrapers. Herald Square Plaza, at the intersection of 34th Street, 6th Ave, and Broadway, is a small urban park with movable tables and chairs, and filled with beautiful landscaping, providing a buffer from busy traffic. Its convenient location near multiple MTA subway lines, bus routes, and the PATH station makes it a popular spot for people to stop by and take a break. The lush green landscape in the foreground and the beautiful architecture, with the Empire State Building in the background, calmed me down from the hustle and bustle of city life.

Newark Avenue and Herald Square have taken the approach to create a strong sense of place and enhance the pedestrian and commuters’ experiences in urban neighborhoods. Though they vary in scale and type, both contribute to the vitality of street life.

TOD: Observations in 2024 from the LYNX Blue Line in Charlotte, NC

Mode: Light Rail – Charlotte Area Transit System (CATS)

Typology: Urban Downtown, Urban Neighborhood, Suburban Neighborhood

Author: Lauren Patterson, PLA, ASLA, with VHB

Charlotte, North Carolina, has a population of almost 900,000 people and is a car-oriented city with 76.6% of the population driving alone to work. It currently is serviced by one commuter rail that runs north-south through the city and is packed during weekday commuting hours. The Blue Line first opened in 2007 and contains all primary amenities for a transportation stop. The experience throughout the corridor, however, varies at different segments throughout the route. There are three primary district types along the corridor: the urban Central Business District, the urban neighborhood, and the suburban neighborhood.

The core of the Blue Line is in the Central Business District and is connected to major amenities of Charlotte such as: the convention center, offices, museums, and stadiums. The transit stops in this area are interconnected to the urban fabric with high-density, mixed-use amenities at every stop.

Examples of the urban neighborhood districts along the Blue Line are SouthEnd and NoDa. South End is a district that has seen an explosion of growth due to transit infrastructure. What used to be a light industrial warehouse district is now a thriving innovative community. Buildings are oriented towards stations, there is safe access to each stop, and mixed-use densities throughout the whole district. What sets this environment apart is the rail trail, art, and residential communities. Increased residential densities adjacent to the rail trail create a very active environment and the art installations define the character of SouthEnd.

The remaining stops around the Blue Line are more suburban in nature. Dated commercial complexes, big box retail, disconnected single family neighborhoods, and strip centers characterize the development near each station. There are few sidewalks, bike lanes, or bus routes that will connect the train to the neighborhood they serve.

TOD: Mockingbird Station, Transit Oriented Development, and District, Dallas, TX

Mode: Light Rail and Bus Transit, Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART)

Typology: Urban Neighborhood/Suburban Center

Author: Taner R. Ozdil, Ph.D, ASLA, with The University of Texas at Arlington

Mockingbird Station is considered as the first TOD in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan region, designed around a multi-modal Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) hub in 2001. Initially, this was a 10-acre infill development in an urban neighborhood that used adaptive reuse strategies for the former Western Electric Building and transformed the station area into a commercial, residential, and entertainment complex with a movie theater, restaurants, and boutiques. When the passenger climbs from the station tunnel to the ground level, s/he is welcomed with a development connected to the existing station by a bridge that crosses the rail line.

The development acts as a neighborhood/suburban center while offering a bus station, park-and-ride facilities, and structural and at-grade parking, which also serves nearby offices, commercial, and multi-family buildings in adjacent lots. Due to population growth and higher demand for the overall district that houses a private university, presidential library, and major office towers within walking distance, the pedestrian network is enhanced further by improved sidewalks, enhanced design for night uses, and added pedestrian bridges to connect nearby blocks, and a regional trail system.

Mockingbird TOD has been significant, if not catalytic, in experience and placemaking because the original project attempted to realize the potential of this light rail station through a uniform development plan for its station area while challenging deeply rooted automobile-friendly culture with multi-modal and mix-use strategies in North Texas. By today’s standards, the development and district still attempt to do all this with medium density and somewhat distinct but segregated uses in a confined area.

Experience of the Mockingbird TOD also made one realize that there is more to be done. The district has opportunities for a stronger pedestrian sidewalks and core, pedestrian-friendly density, and most importantly compact land uses and urban morphology that would cater to 21st century city dwellers in this particular context. The district also calls for adding a variety of affordable living options and revamping its retail, entertainment, and parking options. Most importantly, the TOD must be empowered further as a critical hub for the region by seamlessly connecting the original development with the broader transit-oriented district.

TOD: Transit Oriented Communities in Salt Lake City, UT

Mode: TRAX, BRT, and Commuter Rail of the Utah Transit Authority

Typology: Urban Neighborhood, Suburban Neighborhood, Commuter Town Center

Author: Tyler Smithson, PLA, ASLA, freelancer previously with Architectural Nexus

It’s a crisp April morning as I grab a coffee from my favorite cafe around the corner before hopping on the light rail headed downtown. No battling rush hour traffic, no scrambling for parking—just a quick and convenient ride to work. This isn’t just a dream; it’s a reality for many people living along the Wasatch Front because of the incredible network of the Utah Transit Authority (UTA). With 50 stations on three TRAX lines, numerous BRT stations, and a regional train called the Frontrunner, the UTA connects communities in Weber, Davis, Salt Lake, and Utah Counties.

But it’s not just about getting from point A to B. The future of our growing city lies in Transit Oriented Communities (TOCs) built around these stations. Imagine neighborhoods where everything you need is a 10-minute walk away—shops, restaurants, parks, and more importantly, easy access to public transportation. This is the vision behind the plans to consider transit oriented infrastructure near every TRAX station. However, there is a hurdle to achieving this idyllic vision. Currently, many UTA stations are surrounded by vast parking lots and auto-centric land uses that discourage walkability and create a disconnect between the station and the surrounding community.

Here is the vision: transforming these parking lots into vibrant mixed-use developments with housing, shops, and green spaces is crucial for realizing the full potential of TOCs. This would enhance convenience and foster a stronger sense of community around the station.

These walkable communities wouldn’t just be convenient; they would be good for the environment, too. Less traffic means cleaner air and a healthier planet. Plus, with more people living near stations, TRAX and the entire UTA network become even more efficient, reducing congestion and creating a win-win for everyone. TOCs are designed to be inclusive. By creating a mix of housing options near stations, we can ensure affordability doesn’t become a barrier.

Think about it: vibrant neighborhoods where everything is at your doorstep. This isn’t just about faster commutes; it’s about creating a more connected, sustainable future for all of us. With a focus on TOCs, the UTA’s network could be the key to unlocking a brighter, more livable Wasatch Front. And the best part? This future is just a TRAX stop away.

TOD: Transit Oriented Communities in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada

Typology: Urban Downtown

Mode: Subway, BRT, Regional Transit Hub

Author: Brent Raymond, ASLA, FCSLA, MCIP RPP, with DTAH

I am fortunate to work as a landscape architect and urban designer in one of the most dynamic places on the continent. It is difficult to describe to friends from other cities just how intense and sustained growth has been here in Toronto.

In the early 21st century, the Province of Ontario led an ambitious and award-winning regional planning process called “A Place to Grow: A Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe.” In a nutshell, this plan established an urban structure that identified where growth and intensification should take place. Many of the growth areas are related to existing transit, where others are situated along future planned transit infrastructure. Urban Growth Centres are mixed-use places that will achieve the highest intensity of people and jobs, with a substantial amount of employment related to the highest order of transit. Major Transit Station Areas (MTSAs) are smaller in scale and planned for each station along LRT and BRT lines. In total, there are 25 Urban Growth Centres and 333 MTSAs defined in A Place to Grow.

The most recent program is called Transit-Oriented Communities (TOCs). TOCs emphasize that growth is not just about density yields; each community must first respond to its context and site-specific objectives, and include affordable housing, community services and facilities, and other amenities, such as parks and open spaces, to serve new and existing residents. They must deliver on sustainability and resilience targets and recognize the unique role of Indigenous peoples in shaping the region’s growth and development.

Overall, we are making progress but most of the execution is still to come. A plan of this magnitude is multi-generational in scope. I’m confident that everyone’s efforts will lead to a successful region that transforms from a post-war auto-dominated place to one that is transit-, people-, and nature-first.

TOD: The Yards, Washington, DC Navy Yards

Mode: Commuter Rail (Metro Rail Orange/Silver and Green Lines – WMATA)

Typology: Urban Downtown

Author: Kal Almo, ASLA, AIA, with AECOM

The Yards is a development in Washington, DC’s Navy Yards, a Transit Oriented District located along the Anacostia River. South Capitol Street forms the border to the west, the Dwight D Eisenhower Freeway to the north, and the Anacostia River to the south and east.

I usually take the Metro to get here; the east-west running Orange/Silver Lines that run out of Arlington easily connect to the north-south running Green Line, allowing me to avoid the expense and confusion of parking in DC. I leave Metro at the First St SE exit; my destination today is Yards Park and the Anacostia Waterfront. I could take a bike or a scooter to get around (there are a few of them) but I’m not in a rush and I want to take in my surroundings; walking is fine.

I cut over to an allée along New Jersey Avenue that leads to Tingey Plaza, a neighborhood-scaled park with integral seating formed by intersecting rectilinear concrete, steel, and wood planes. The allée also parallels one of the more prominent inland BMPs, an 8’ deep swale planted with trees, shrubs, and tall grasses, an aesthetic counterpoint to the grid of plantings along the street edge. I turn down Quander Street, appreciating the swale/copse, then take a left down Yards Place, where designers have placed the sidewalk at road level, used cobble paving, and narrowed the distance between buildings, effectively creating a woonerf. Other area streets seem scaled to the crowd; N Street and Tingey Street can feel almost empty without the frequent arena-scaled events. However, even as construction continues, Yards Place feels more intimate.

I leave Yards Place, go to Tingey Plaza, and then walk along the dentil-capped masonry wall surrounding the brick and stone buildings of the Pump Station. I soon see the tops of the arches forming the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge (connecting the two shores of the Anacostia River). Next, I see the wheelhouses of the larger private boats; then a person-scaled, transparent, red panel with the letter “e” (one of seven colored panels that together state “w|at|er is li|f|e”). I have arrived at Yards Park, my destination.

Yards Park is a regional attraction and part of a string of parks (including Diamond Teague, Dahlgren, and Willard Parks) that form the green edge of the Anacostia River. Designed by M. Paul Friedberg and Partners, it features a boardwalk, a splash pool, expansive views of the river, a stepped lawn, and a pedestrian bridge. I meander within the cobbled plaza, through the great lawn, against the green wall next to the splash pool, under the bridge, and along the boardwalk, finally stopping in the courtyard between two-story buildings containing restaurants. Near nightfall, I look back through the copse of trees towards the bridge and the river.

Time to head back home.

References

ASLA (2024). Transportation + Urban Design PPNs Webinar Panel: Transit Oriented Development.

Dittmar, H. and Ohland, G. (2004). The New Transit Town: Best Practices in Transit-Oriented Development. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Government of Ontario (2024). Transit-Oriented Communities.

Government of Ontario (2020). A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

Ozdil, Taner R., & Taylor, P., & Li, J. (May 2012). Transit Oriented Development Research. NCTCOG University Partnership Program. 294 pages.

Ozdil, T. R. (March, 2014). What is Next for Sunbelt Cities? Why it’s Time to Start Thinking about TODistricts. ASLA, The Field.

Authors

Taner R. Özdil, Ph.D., ASLA, is an Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Affairs, at The University of Texas at Arlington. Officer and Past Co-Chair of the ASLA Urban Design Professional Practice Network (PPN) since 2013. He is serving as 2024 CELA Theme Track “Taking Action: Making Change” Co-Chair, and President-Elect for the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA). His scholarly and professional work primarily explores environmental, economic, and social value creation, resilience, and performance through landscape architecture, urban design, and physical planning in mixed-use environments, urban areas, and metropolitan regions.

Kal Almo, ASLA, AIA, is a landscape architect, project manager, architect, and urban designer currently working at AECOM in the Buildings + Places group. He is also serving as a Member-at-Large for the Potomac Chapter of ASLA. His interests include landscapes over structures, the integration of landscape and architecture elements, and resilient landscapes in the urban environment. In the past several years, he has led landscape architecture and architecture design projects that range from re-envisioning urban streetscapes to creating design guidelines for federal campuses. He has worked within a variety of market sectors including commercial, health care, arts & cultural, government, and higher education projects.

Lauren Patterson, PLA, ASLA, is a Landscape Architect and Planner with over 10 years of experience leading projects from large scale regional planning initiatives to detailed immersive designs. She is a Planning and Design Project Manager at VHB in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her work focuses on evidence-based design throughout all phases of a project that allows her to meet community and client needs. She has worked on a wide variety of projects throughout the United States and is involved in a variety of outreach and advocacy for smart planning and design initiatives throughout the country.

Jenny Zhang, Associate ASLA, AICP Candidate, is an Urban Designer with two years of experience in transit-oriented development (TOD) master planning, land-use planning, development feasibility study, streetscape design, and public space design. With a background in landscape architecture and urban design, she takes a holistic approach to tackling complex urban issues with a passion for creating memorable places and vitalizing public spaces.

Tyler Smithson, ASLA, is a seasoned landscape architect in the Intermountain West who thrives on crafting sustainable communities through transit-oriented design, advocacy, and a collaborative spirit.

Brent Raymond, ASLA, OALA, FCSLA, MCIP RPP, is a Partner at DTAH in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Brent is a landscape architect and planner whose primary interests are related to city building, with a particular focus on built form guidance, public realm design, and streets.

LEAD IMAGE: Mockingbird Station, Dallas, TX / image: Taner R. Ozdil

Reimagining Abandoned Airfields Through Adaptive Reuse

By Anhad Viswanath, Associate ASLA

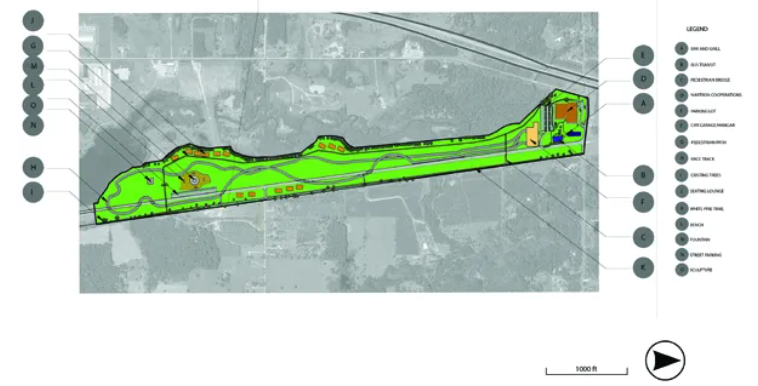

This post discusses “Reed City’s Exhilarating Thrust,” a design concept I crafted while a student at Michigan State University that illustrates the wonder and excitement that the race circuit brings. The design includes a four-mile racetrack with elevated inclines over an existing road, housing, and spaces for residents and visitors to socialize and enjoy the races. Pedestrian bridges, trail connections, and a bus transit hub create multimodal connectivity.

Globally, many airports face an uncertain future, and some are at the brink of closure. In the United States, there are 20,000 functional airports (private, commercial, and military), and 1,000 more that are abandoned, on-hold, or underused. This represents both a significant issue moving forward, and also a significant opportunity for reimagining these built environments.

According to a Developments in the Built Environment article on the former Hellenikon Airport in Athens—now being developed into Ellinikon Metropolitan Park—airports, or airfields, are a type of built environment where there is a relatively low density of infrastructure and are characterized by open spaces. Airports cover large portions of land and encompass various types of facilities that can often exacerbate environmental issues for surrounding areas. This makes airports, especially abandoned airports, capable of damaging the environment and wasting land and resources.

Landscape architects have long been interested in reimagining abandoned spaces. Some interesting ways in which abandoned land, like former airports, are reinvented include parks, gardens, and playgrounds, offering recreational activities, including biking. In turn, remaking abandoned spaces into new landscapes not only helps in reusing and utilizing resources more effectively, but also provides an opportunity to craft innovative places.

A couple of case studies highlight amazing ways in which abandoned airfields have been imagined. One excellent example is Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, Germany, part of which was reimagined in 2015 to serve as a location for Formula E races and events. The program elements include a 17-turn track, a park, and an event center. Another example is Xuhui Runway Park in Shanghai, designed by Sasaki.

Goa Dabolim International Airport, Goa, India / image: courtesy of Anhad Viswanath

Fall 2023 Senior Capstone Project: Reed City and Nartron Airfield

This project was an independent evidence-based adaptive reuse design proposal for my Environmental Design Studio class in Fall 2023. The design involved reimagining an abandoned airfield in Northern Michigan into a sports car race circuit that would serve as an amazing tourist landmark.

Race track design / image: Anhad Viswanath

The project site is Nartron Airfield in Reed City, Osceola County. The airfield is identified on pilot Paul Freeman’s Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields website. In 1945, James T. Miller started Miller Industries, and subsequently opened Miller Airport to streamline business operations with his customers through air connectivity. Growth in business and sales led to the formation of Miller International Airport that connected Reed City with Grand Rapids and Chicago. James Miller then sold off the company to Norman Rautiola, the founder of Nartron Corp., in the 1980s. However, Rautiola found a new opportunity elsewhere and shifted operations north, abandoning the airfield.

The airfield has been abandoned for thirty years; the site has a cracked runway and an unused terminal building. Yet, it is well placed in between two state highways and two state trails. That makes the airfield accessible and in a position to bring in more people and tourists to the area. Reed City is known for campgrounds and some interesting outdoor landmarks, including the Purple Heart Trail.

Exploring activities popular in northern Michigan, including winter sports, sparked the idea to bring something novel and global to Northern Michigan that would contribute to tourism. The square footage of the airfield and the proximity to Grand Rapids and Cadillac presented an intriguing opportunity to design a race circuit that would attract more tourists from different parts of the state and beyond, and provide a vibrant and exciting ambience.

Master plan / image: Anhad Viswanath

Design Concept

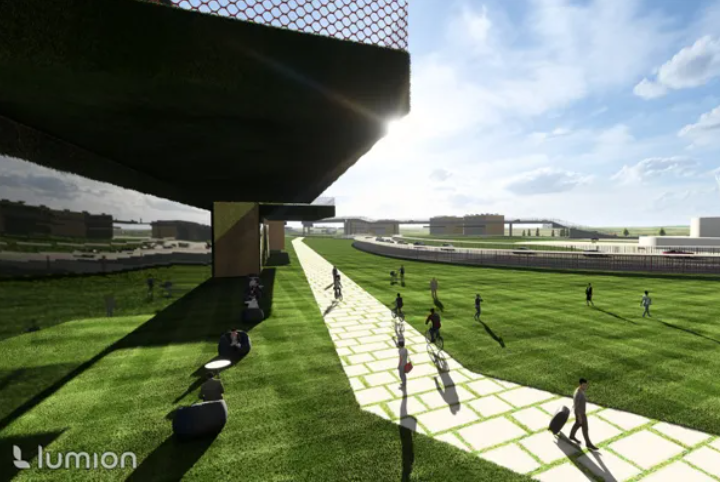

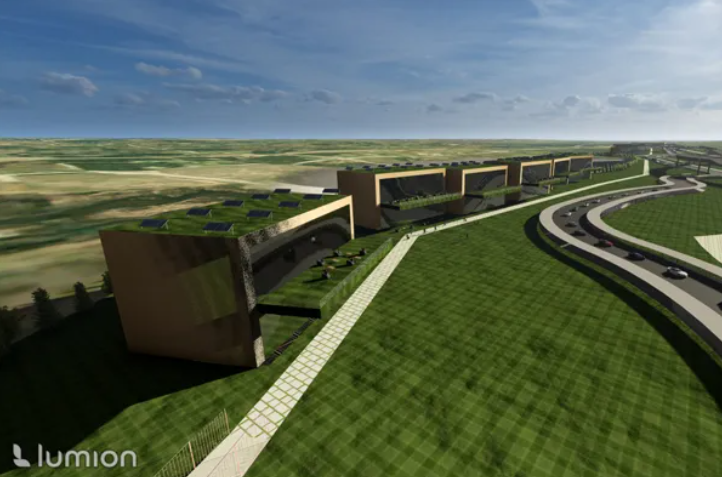

The design brings together a concept that I crafted, “Reed City’s Exhilarating Thrust,” illustrating the wonder and excitement that the race circuit brings. The design includes a four-mile racetrack with elevated inclines over the existing Old US 131 road. There are some condos for users to socialize, eat, and enjoy the race. The pedestrian bridges streamline connectivity with the White Pine Trail, along with a bus transit hub to support bus routes and add multimodal connectivity to the site for tourists.

View of the condos / image: Anhad Viswanath

Ground seating at the condos / image: Anhad Viswanath

Recently, I was reviewing my design proposal and exploring how I could continue to develop the idea as an emerging professional. After reading about sustainability in race circuits and Formula 1’s pledge to work towards a net zero carbon footprint, I began to contemplate how I could refine my design to add important sustainable measures and make the circuit environmentally friendly.

Pedestrian path / image: Anhad Viswanath

Condos with green roofs and solar panels / image: Anhad Viswanath

I saw that there was room for more sustainable techniques for better energy efficiency. That led me to add solar panels to the roofs of the condos. Additionally, green roofs can reduce the heat island effect during the summer and contribute to reducing the carbon footprint. Moreover, the vegetative surface of the green roofs could absorb sound and contribute towards reducing the impact of noise pollution caused by the sports car engines.

—

Anhad Viswanath, Associate ASLA, is a Michigan State University landscape architecture program graduate, originally from India. I chose landscape architecture because the field offers interesting avenues for design, art, the environment, and society, which are my interest points. I spent seven years of my childhood in the Netherlands. During my time there, I witnessed landscape architects and agriculturists employing interesting means, such as marshes, dikes, and adding volumes of sand to land near the seashores, to protect the land from flood related events. I saw how the profession is very important in helping the country’s landscape become and remain resilient and regenerative, especially as the country is situated slightly below sea level. I would like to specialize in landscape and urban design where I can design gardens, parks, playgrounds and urban spaces that can encourage people to embrace the natural environment and improve the lives of communities. My capstone project in my graduating semester allowed me to explore adaptive reuse and eventually discover my passion for reimagining airfields and underutilized developed land as a part of sustainable design.

Featured Image: ASLA 2021 Professional Urban Design Honor Award. Xuhui Runway Park. Shanghai, China. Sasaki / image: Insaw Photography