Author: Mayré Rivero Bueno

Colombia’s Got Talent – 10 Examples of Colombian Design

Continuing on with our world series, we have selected 10 projects that represent Colombian design. Colombia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world with 40,000 to 45,000 plant species, which is 10 to 20 percent of the total global species and holds the top spot for number of bird species—surpassed only by Brazil. The country is home to Rogelio Salmona (1929-2007) a Colombian architect that worked with Le Corbusier for six years at his studio in Paris from 1948 to 1954. Rogelio is among Colombia’s most celebrated modernist architects; he is the author of multiple architectonic and urban landmarks—most of them are found in Bogotá. So, let’s take a look at some known (and some not-so-known) projects in Colombia.

10. Parque Bicentenario (Bicentenario Park), by The Mazzanti Team, Bogotá

A bridge is an element that connects two points. The Mazzanti Team took this concept and elevated it, making it greener. To do this, they took a section of 26 Avenue and covered it to create a 4.6-hectare (11-acre) park that was designed to help revitalize a neighboring park. The park consists of eight small vegetated squares full of native and easily adapted plants. In total, there are 41,000 plants.

Bicentenario Park. Credit: GreenRoofs

9. Parques del Río (Parks by the River), by Latitud, Medellín

With its first stage barely completed, this is the most ambitious mega-urban project in Medellín. Ultimately, the project’s intent is to connect both sides of the river through pedestrian bridges and linear parks. With a ten-year schedule, its first stage was delivered last year and it’s ongoing. Slated for completion in 2026, it will become the largest public green space in the city.

Parks by the River. Credit: Antonio Maggiolo

8. Park Citadel 29 of July, by The Mazzanti Team + AEV Architects, Santa Marta

This project is part of a plan to recover the Manzanares Riverfront in Santa Marta. Through the city’s hydrological system, the design team crafted a network of recreational spaces across the riverfront. Featuring a synthetic soccer field, a playground, an adult gym area, a multi-purpose area, multiple gardens, and pedestrian walkways—it’s a popular spot for families.

Principal Park Agueda Gallardo Recovery. Credit: Andrés Valbuena

7. Principal Park Agueda Gallardo Recovery, by Arquitectura y Espacio + Carlos Puebla y Verónica Cruz, Pamplona

Despite its small size, the city decided to rejuvenate the Principal Park Agueda Gallardo as a place for people to meet and gather. The general design concept is based on the linear nature of the space and its simplicity. All of the urban furniture is also designed in accordance with this principle and made with natural materials like wood, stone, and black metal. The green areas and terraces include two green zones and strong geometric shapes.

Principal Park Agueda Gallardo Recovery. Credit: Sergio Gomez

6. Bulevar del Río (River Boulevard), by Elly Burckhardt, Cali

Located in the city’s historic downtown and atop Colombia’s longest urban tunnel is River Boulevard. The main idea was to give this place back to pedestrians and cyclists by eliminating dense traffic and pollution. Subsequently, just a small part of the public transportation system now drives on this zone at a very slow pace. In 2014, the Colombian Society of Architects named the boulevard as “Best Urban Design of the Country”.

River Boulevard. Credit: Jorge Bela Kindelán

5. La Ronda del Sinú (Sinú Riverfront), by Parques Nueva Montería, Montería

The construction of the longest linear park on the Caribbean Coast of Colombia transformed First Avenue and reconnected it to the Sinú River. Throughout its length there is a pedestrian walkway and a bike lane that twists around the gigantic shade trees, which help reduce the urban heat island effect and makes the experience more comfortable. One will also find an art museum (The MUZAC), a commercial zone, children’s playgrounds, and an outdoor theater.

Sinú Riverfront. Credit: Alejandro Rincón

4. Public Library Park and Cultural Center Julio Mario Santo Domingo, by Diana Wiesner Ceballos + Daniel Bermudez, Bogotá

With a public space of 5.5-hectares (14-acres) this library offers an experience like no other. Aiming to be a low-impact construction, recycled materials were used but the most interesting work was done in the surrounding green spaces. The library is nestled in an immense green area where one can find playgrounds, wooded green space, and pedestrian walkways.

Public Library Park and Cultural Center Julio Mario Santo Domingo. Credit: Daniel Olarte

3. Orquideorama, by Plan B-Felipe Mesa, Alejandro Bernal + JPRCR-Camilo Restrepo, J. Paul Restrepo, Medellín

Situated in the Botanic Garden of Medellín, Orquideorama is a perfect example of how architecture fuses with nature. Orquideorama is a floating meshwork of modular “flower-tree” structures. Each “flower-tree” is comprised of seven hexagons and fitted into each other, which helps control the expansion and allows for the option of continuous growth. The design is part of the environment and it links with the plants, creating a forest-like atmosphere.

Orquideorama. Credit: Sergio Gomez

2. Santalaia Residential Building, by Exacta Proyecto Total + Paisajismo Urbano, Bogotá

The Santalaia Residential Building is located east of Bogotá, in one of the most densely populated areas of the city. The project boasts one of the largest vertical gardens in the world covering 33,551 square-feet and is home to more than 115,000 plants of ten different species. The project goes beyond a mere aesthetic goal and creates an impact through ecological alternatives.

Santalaia Residential Building. Credit: Daniel Segura Photography

1. Parque del Agua (Water Park), by Lorenzo Castro y Juan Santamaría + Alfonso Leiva y Michel Cescas, Bucaramanga

Reopened to the public in 2003 after being closed for over a decade, Parque del Agua was revitalized to reintegrate its area into the urban fabric. The design is a strict orthogonal geometry with rustic finishes that work collectively with the lay of the land. Additionally, the furniture also follows this geometry while water delineates the pathways and shapes the character of the different spaces. The park has been given multiple international and national awards and the Colombian Society of Architects declared it one of the most significant works of Colombian architecture from the last 25 years.

Parque del Agua. Credit: rugB66’s via Flickr

Colombia is a multicultural country where we find many backgrounds, climates, and design styles. Whether it’s Santa Marta, Pamplona, or Medellín—each of the selected projects reflect the region’s context and current need.

Recommended Reading:

- How Pantoja Architects’ Latest Landmark is Bringing Back Colombian Art by Nour Adel

- Ground Breaking Master Plan Redefines the City of Bogotá by Rachel Kruse

Featured image: Chorro de Quevedo en La Candelaria |Bogotá, Colombia | Pedro Szekely | 2010

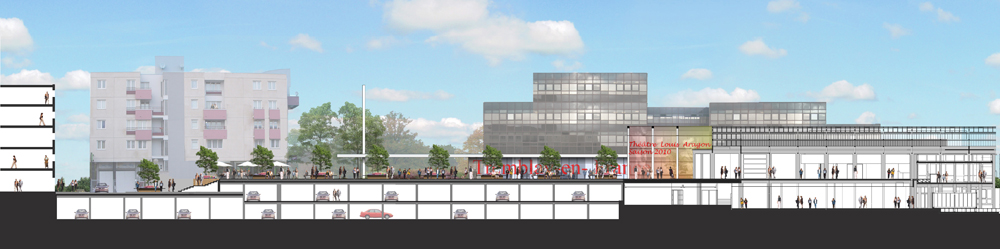

Place des Droits de l’Homme | How to Bring People Back to a Forgotten Space

We take a look at how the Place des Droits de l’Homme project brought people back to a space that was forgotten about, rejected by time and life. The square, Place des Droits de l’Homme, is located in Tremblay en France. The town is a commune in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris, it has an area of 22.44 Km2 and is 19.7 Km from the center of the capital city; using public transportation, it would be a 1-2-hour trip. The square has a strategic location and has existed since the 70’s; it is surrounded by the town hall, the cultural center, the municipal library and housing, and it is the cover for an underground parking lot. The square has always been viewed as an essential piece of the city center but as time passed the space became neglected and forgotten, slowly becoming a mournful space, disconnected from the city.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

Place des Droits de l’Homme

The Conflicts

The square was having conflicts in achieving a strong and good connection between the city and the citizens, because it didn’t have a fluid connection with its surrounding space. The fact that it is 2 meters above the natural ground level was one of the reasons, plus there were elements such as misplaced urban furniture that acted as obstacles which increased the problem; those fringes reinforced the isolation of the square.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

These physical barriers needed to be softened because it also created an un-friendly scenario for people with reduced physical mobility. Another not-so-helpful characteristic was the square’s floor, it was a paving slab system that consisted of paving slabs over pedestals, sitting above a weatherproofing membrane. This system was really fragile, as it only permitted a maximum of 350 Kg/m2, limiting the versatility of the square, discouraging the presence of temporary markets or other uses; it also created difficulty for placing vegetation, plus the slabs started to deteriorate with time by breaking down.

Solving the Conflicts

The square was lacking multifunctionality and this was not only a mere aesthetic issue. The designers had to solve the enigma of how to transform the square in a dynamic and static space, a transit zone and contemplation zone. The design should permit the square to be flexible, in order to be the scenario for different types of events; it should not be predictable, as it had to leave a sense of freedom where different types of activities could take over.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

As a design guide, the team created a square grid of 3.5 m by 3.5 m. They placed it over the square; this mesh worked as a skeleton structure that shaped the new square’s design, and it also gave birth to the new pattern for the square’s floor. The paving slabs were replaced by concrete squares that could hold more than 350 Kg/m2, so the matter of the new maximum structural loading was one massive improvement, maybe the most relevant portion of the redesign, because now the square was not tied down to that maximum weight restriction that inhibited the opportunity to have green landscape and different kind of activities.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

Other specific changes had to be done; towards the south we can find the Jardin des cultures. This access was frequently used but was visually blocked and created a feeling of insecurity; the solution here was to insert a new monumental staircase that created visual connections.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

To the north is the Boulevard de l’Hôtel de Ville; this connection has one of the entrances to the sub-level parking lot. This zone was not as pedestrian-welcoming as was wished, it had also visibility issues and for citizens with reduced mobility was not a friendly access point, so here the team took a previously existent pedestrian access and turned it into a ramp so that people on bikes and wheelchairs could also use it. Furthermore, the existing vegetation is reinforced and this seals the engagement of the boulevard with the square.

To the west, we find the Allée Nelson Mandela; here, in particular, many misplaced elements were acting as obstacles towards the fluidity and legibility of the space, such as low walls, banks, etc; also there was no access for people with reduced mobility. The response here was to demolish the misplaced elements and free the space, plus the design of a fusion of a stair and a ramp with vegetation and lighter guardrails. The result turned out very sculptural; this increased the aesthetic value of the zone.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

The Vegetation

We talked before about the square grid of 3.5 m by 3.5 m. Those measurements were also the dimensions of the new micro-gardens; they are easily movable and divisible into 4 parts. On each of the micro-gardens were planted a different kind of trees and flowers. Within the trees we find Scots pines, magnolias that are the evergreen type and maples which are the type that change their color through the seasons.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

The flowers are perennials, wildflowers are ivy, wisteria, poppies, wild chrysanthemums and more; these types of flowers bring color, plant diversity, and micro-fauna such as butterflies and ladybirds. The vegetation has the ability to revitalize a place; these green pixels helped this square to become a true outdoor living space where people pass by and also actually stay. If citizens don’t feel comfortable in a place they will just avoid it and neglect it as much as they can; this, for a public space, is a key factor for its death or life.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

A public space without users is nothing but an urban desert, an easy scenario for not-so-friendly activities. It has been said and written multiple times that multifunctionality is key for the success of public spaces because it helps a space respond to different types of needs that the users and the city may have and allows it to function during any season. This is what was solved through the re-design of this square; the multifunctionality that was missing in the space was brought to the fore, and it revitalized the place, bringing back citizens. Do you think that this so-called multifunctionality has any negative side effects on public spaces?

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Baye

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

The Floating Piers | The Artists Who Made It Possible to Walk on Water

The Floating Piers, by Christo And Jeanne-Claude, in Lake Iseo, Italy. For more than 40 years, the artists had this vision of a floating walkway; the project was first conceived by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1970 but not actually brought to life until 2016. It was Christo’s first large-scale project since 2005 when he and Jeanne-Claude realized The Gates in N.Y.C., and since Jeanne-Claude died in 2009. In 2014, when Christo and his team explored Northern Italy’s lakes, they found Lake Iseo to be the most inspiring location of them all. Lake Iseo or Lago d’Iseo is located 100 Km east of Milan and 200 Km west of Venice and is the fourth-largest lake in Lombardy, Italy; the lake is fed by the Oglio River. Through the work of Christo and his team, the place was reimagined and transformed and became the habitat and witness of a miracle coming true; to be able to walk on water. WATCH >>> MAKING OF “THE FLOATING PIERS” BY CHRISTO // ISEO LAKE // ITALY // JUNE 2016

The Floating Piers

The Floating Piers (TFP) consist of a Modular Floating Dock System of 220.000 high-density cubes covered with 100.000 m2 of a yellow cloth that changes its color depending on the weather and time of the day; it goes from a bright yellow to shades of red and gold. The cubes are joined on the sides with giant screws that pass through a ring-shaped protuberance; this connects the cubes to each other and at the same time allows movement.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

The Floating Piers go from Sulzano to Monte Isola to the Island of San Paolo; the last one is framed by the Floating Piers. The walkway is 3 Km long but the fabric continues along 2.5 Km of pedestrian street in Sulzano and Peschiera Maraglio. The piers are 16 meters wide and 35 cm high with leaning sides; to create the leaning sides effect the outer cubes were filled with water.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16. Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

The construction of the piers in situ started on April 19 and was finished on June 18, the Floating Piers were opened to the public only for 16 days and nights, meaning it was open from June 18 to July 3 of 2016. On June 18 at 7:48 in the morning, the piers were finally opened to the public; it had no cost, no tickets, the access was completely free as in all of their projects, but visitors should be prepared for long lines, because for safety reasons only 11.000 people could be on the Floating Piers at the same time.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

The Impact On the words of Christo, “TFP was an extension of the street and belonged to everyone”, here the artist is making a statement when he says, the street belongs to everyone, and let’s understand the term street as public space; this vast concept that wakes up all kinds of feelings and discussions, therefore the relevant fact is that he uses public space as the scenario of his work of art and in that way makes his art belong to everyone just as public space belongs to everyone, but he is also creating public space through his intervention, it is almost like his work of art is to create unimaginable public space.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

When you step in to a specific space and bring something new to that habitat – in this case, the artist brought a new and never-before-seen attraction to the town – there will be many consequences, some more tangible than others but the city and its citizens will respond to that stimulus. One of the more tangible responses was economic; the nearest stores were out of stock of their products the first day because of the many new costumers that came to see TFP and in some stores they were even selling “special socks” for walking on the Floating Piers.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

What is incredible is how the artist empowered people to take this temporary street and making it theirs as if they were living a fantasy. When asked about their experience in the TFP people responded things like: “It’s massive, it’s hard to describe, we’re so exited”, “It’s like walking on water. It’s wonderful”; others even said it felt like walking on the back of a whale.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

For Kevin Lynch to have places where we could contemplate a city was an important part of feeling that you belonged to a city, of feeling you were a citizen. This project created a new point of observation, a new experience, a new way to contemplate that specific habitat; in conclusion, the project enriched the experience of going to Lake Iseo forever, even when – physically – it is no longer there, that happening will stay on in the collective memory of people for a long time. Well thought-out and executed art can transcend itself and become part of the landscape and the memory of the people.

Do you think that art should come out of the museum more often and directly impact the life of a city?

*After the 16 days all the elements were removed and industrially recycled.

The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16 Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2016 Christo

Full Project Credits For The Floating Piers:

Project Name: The Floating Piers

Artist: Christo And Jeanne-Claude

Christo’s Project Team: Vladimir Yavachev – Operations Director, Wolfgang Volz – Project Manager And Official Photographer: Josy Kraft – Registrar/curator And Germano Celant – Project Director.

Location: Lake Iseo, Italy.

Area: 100.000 M2

Total Project Value: 16’000.000 E

Funding: The Artist Own Money

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

How an Old Market Square Became the New ”It” Spot

Old Market Square, by Gustafson Porter, in Nottingham, England. In 2004, the Development Department of Nottingham, England, organized an international competition for the re-design of the Old Market Square. The winners were Gustafson Porter and Bowman, and the design was so clever that the Old Market Square of Nottingham became the nerve center of the city’s social and cultural life. The square holds a strategic location within the city and is connected with spacious avenues and streets that create quick routes across the compact center. Those avenues and streets are filled with relevant places for citizens and visitors, such as restaurants, libraries, hotels, banks, department stores, and tram stops.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

Old Market Square

In its new role as social catalyst, the square is now home to many community events. During the summer, it transforms into the Riviera Beach, an urban beach setting with bars and different attractions. During the winter, the space becomes the Christmas Winter Wonderland, where people can enjoy skating at an ice rink. Throughout the year, visitors can browse farmers markets to easily buy local products.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

The square has become an important landmark and node for Nottingham’s citizens. It is the second-largest square in the United Kingdom, after London’s Trafalgar Square. Nottingham’s square is also one of the oldest in the country, with 800 years of history. “The project has been well received by the citizens of Nottingham and is well used both in attending events but also using the seating areas to relax and meet. Previous issues associated with antisocial behavior have effectively disappeared with the new design,” said City Council representative Steve Hunt.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

Why Re-design?

The idea to re-design the square came out of the city’s need to stage cultural and civic events. The previous 1929 design by architect T.C. Howitt — who was also responsible for the design of the contiguous Council House Building — was poorly lighted and created a not-so-welcoming atmosphere, especially during the night. Through various studies, it was determined that 78 percent of pedestrians crossing the square avoided the center of the space, due to the many steps and low walls. The only group that enthusiastically used the space was skateboarders.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

So when the city’s Development Department organized the competition, its members knew what they wanted in the square and had very specific requests for the competition’s participants. The proposed design had to encourage 24-hour use, integrate street furniture, attract pedestrians, allow access for all, use high-quality materials, create water features, enable perimeter use, and — most importantly — provide a flexible performance space. Summing up, the place had to be innovative and attractive; it needed to be a place for the people.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

The Design

The landscape architects used the natural topography of the original medieval square to guide the design. The different levels of the square played a protagonist’s role in the final result and in the way that the space is now enjoyed. The topography was used as a natural drainage system, with soft, gradual level changes — which also happened to work well for wheelchair users. The 4,400-square-meter water feature contains a reflecting pool, a 1.8-meter-deep waterfall, rills, 53 jets, and a scrim aligned in four terraces. The water can be turned off and the space used as a stage or viewing area when required. Even with the water turned on, the terraces provide seating and contemplation spaces.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

The terraces each have a different color — gray, black, white, and beige — to delineate the level changes. They are made of granite blocks, the predominant material used in the entire square because it provides durability. The colors also aim to reflect the color palette of the surrounding building facades. Planters aligned with box hedges have been placed on the north side, creating intimate spaces that facilitate passive recreation and provide more seating places. This space is the green brushstroke of the design. A frontier between the Long Row and the square is made with a line of Ginkgo Biloba trees; these trees reach 50 to 80 feet or more in height, with a spread of about 30 to 40 feet. The fan-shaped leaves turn a golden-yellow tone during the fall.

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

The box hedges are full of thousands of colorful flower bulbs and perennials, and there are hundreds of shrubs. Toward the south and west, on the South Parade, stand Pin Oak trees that reach 75 feet tall with a 40-foot spread. Their leaves turn bright red-brown during the fall. All of this unites and generates a composition of colors and shapes that transform constantly through the different seasons. The new Old Market Square of Nottingham is a place for the community, thanks to a well thought out design. Gustafson Porter was able to revitalize a place that was dead and bring it back to life. The square is now an important landmark and node for the citizens, who can now actually enjoy it as the center of social and cultural life in the city. This project is one of the most tangible demonstrations of why good quality public spaces are vital in making a city livable. So, do you agree on the relevance of public spaces for a city’s quality of life?

Old Market Square. Photo courtesy of Gustafson Porter

Full Project Credits For Town Centre of Meilen:

Project Name: Old Market Square Landscape Architecture: Gustafson Porter Client: Nottingham City Council Gustafson Porter Project Team: Neil Porter, Nilesh Patel, Dominik Bueckers, Ines Marcelino, Kinna Stallard, Pauline Weiringa Engineers: Ove Arup & Partners Ltd Quantity Surveyors: Davis Langdon LLP Lighting Designer: Speirs & Major Associates Pedestrian Study: Space Syntax Ltd Conservation Consultant: Jules Renfrew Associates Main Contractor: Balfour Beatty Civil Engineering Ltd Water Feature Specialist: OCMIS Ltd Commencement and completion: 18 months (October 2005 to March 2007) Total Project Value: £ 8.8 million

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

How to Keep Heritage Alive Through a Military Museum

National Military Museum, by H+N+S Landscape Architects, in Soesterberg, Utrecht, the Netherlands. The Netherlands have already shown us that they clearly know what landscape architecture is about and the National Military Museum (NMM) in Soesterberg is not an exception. The former Soesterberg Airbase that was officially out of service on 12 November of 2008 was brought back to life in 2015 as the National Military Museum (NMM), as a result of the integration of the Army Museum and the Military Aviation Museum. The complex is composed of a 100 x 250 m building, an arena, and a surrounding natural landscape full of military, war and aviation relics and landmarks. The firm in charge of the mission was H+N+S Landscape Architects, based in Soesterberg.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

National Military Museum

The placement of the project has a vast significance in Dutch Military history, as the Dutch Aviation base during WW2 and the Cold War. That gives us an idea of the massive cultural and historical relevance that this area has; there are physical elements (the military, war and aviation relics and landmarks we mentioned before) that are placed in the landscape that surrounds the museum building, and of course that entire heritage worked as a main determinant to develop the final design. These elements such as preexisting monuments, abandoned bunkers, bomb craters and the air base itself, among others, guided the placement of the museum building and the way it is connected with the surrounding landscape.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

The Building and Exterior Elements

The museum building is aligned with the old plane runway and is placed diagonally to four ancient T2 hangars; the sides of the building are completely see through to use the surrounding landscape as a background for the collection pieces on exhibition. One side of the building is open to the panoramic view of the landscape that brings in the large-scale runway.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

The other side of the building is hugged by a dense forest where we can find some old bunkers, bomb craters, shelters and sightlines, most of them were left in situ and had some minor additions, therefore the experience of the museum visitors continues outside the building as they walk through military relics and war scenarios. The purpose of keeping these elements is also historical and ecological; the bunkers and bomb craters remind visitors of the German occupation of May 5th in 1940 and the Allied bombing at the end of WW2.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

The craters, besides that visual impact and the educational value that they already possess, also work as water collection points that help to develop a micro-ecological environment. Around the property we can also find a lot of gabions. These components don’t just have a functional purpose, they are remembrance elements and are a representation of the woven wicker baskets that in medieval battles times were used by the Netherlands troops as shelters; the gabions have the height and form of the former shelters.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

The Surrounding Landscape

As we mentioned before, the building is surrounded by two very different scenes on each side, on the side with the dense forest and the multiple elements there is a design of pedestrian paths and vehicular roads that allow visitors to move in different ways and directions, which lets them to create their own experience.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

The spinning vehicular roads lead to the different car parking spots that the complex possesses; these are usually close to bike stands and charging points for electric cars and bikes, and the parking spots have pedestrian paths that directly conduct visitors to the Museum building entrance.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Other landmarks of the outside landscape are the Memorial Square and the Royal Netherlands Airforce Memorial Garden, which are connected through a curved pedestrian path that surrounds the beginning of the forest. A dense forest in a landscape is an advantage because as a result we have an area with a thick and tall tree population that enriches the design.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

After the visitor passes the Memorial Garden and continues to follow the suggested pedestrian path, they will find a Commander Bunker, then they will pass by one of the double functional craters and before arriving to the museum entrance they are welcomed by an open space big enough to let the visitor contemplate the magnificence of the building and the forest itself.

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Overpassing the Museum entrance is the Arena; this amphitheatre is the largest outdoor theatre in the country; it can accommodate more than 3.500 people at once, and is home for the largest Tank show in the Netherlands where over 30 tanks and armoured vehicles make an appearance in the NMM Arena. This project helped to reinforce a cultural legacy, this design is completely contextualised in every aspect. H+N+S showed us why we, as creators, need to be connected with the past, present, and possible future of the places we are going to work in, so we can answer correctly to the need we are trying to satisfy without harming the surrounding natural environment. What do you think about preserving our heritage; does that stagnate us or educate us?

Military Museum. Photo credit: H+N+S Landscape Architects

Full Project Credits For The National Military Museum :

Project Name: National Military Museum Location: Soesterberg, Utrecht, the Netherlands Date of Construction: 2011-2015 Size: 45 ha Cost : 90.000.000 euro (design + construction) Client name: Government Buildings Agency and Ministry of Defence Designer: H+N+S Landscape Architects Team: Felix Claus Dick van Wageningen Architecten (architect) Kossmann.deJong (exhibition architects) Heijmans PPP (contractor) Buiting Advies (ecological consultancy)

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network