Seventeen months after

Superstorm Sandy left a trail of destruction through the U.S. eastern seaboard,

Rebuild by Design competition’s ten design team finalists have unveiled their resilience-based solutions after eight months of intensive research and public outreach. The international competition was launched by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force last year in an effort to defend the mid-Atlantic region from increasingly temperamental weather events. Here at Land8, we take at look at some of the proposals by top landscape architecture firms.

Hurricane Sandy is estimated to have caused the United States

$68 billion in damages, a cost only surpassed by Hurricane Katrina. Some communities

have yet to fully recover from the storm. Since Sandy’s aftermath, people wondered why the U.S. wasn’t better prepared. Didn’t we learn our lesson from Hurricane Katrina? Should people even be allowed to live in a flood zone?

Rebuild by Design is the largest of the design competitions to result from Sandy. “It is clear that we cannot simply rebuild what existed before. We need to think differently this time around, making sure the region is resilient enough to rebound from future storms,” says HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan. The final design proposals unveiled last week show a diverse array of approaches to the problem of coastal sustainability and range from the environmental (barrier islands, wetland restoration) to the commercial (enhancing neighborhood retail corridors). A common theme throughout the proposals–whether the teams comprised architects, planners, landscape architects or educators–was the attention to landscape as a core component to battling the undiscriminating power of storm surges and rising tides.

Among the ten design teams, four feature landscape architecture firms with major roles:

OLIN,

Sasaki,

Scape, and

West8.

Let’s take a look at the proposals:

Images ©TEAM WXY / West 8

Blue Dunes: The Future of Coastal Protection

WXY / West 8

Barrier islands have existed for a long time and occur naturally along coastlines worldwide. Scientists aren’t in consensus about how they form, but their protective properties are no mystery. Using financial and hydrodynamic modeling tools, WXY and West 8 researched the potential impact of placing new barrier islands along the coast in a long chain of dune-like formations. The Blue Dunes would act as a buffer for storm surge and wave action, taking the strength out of a future Sandy before it hits land.

The approach to protecting the coast comes not only from an ecological perspective but also a financial one. A core component of the proposal includes cost savings from less future investment in hard infrastructure such as seawalls, as well as active economic generators in the form of offshore wind energy.

WXY/West 8’s proposal stems from scientific analysis regarding the mitigative properties of barrier islands as well as research into the their potential economic benefits. It’s an enormous, earthen shield for the communities on shore, and it’s designed to be a lasting solution.

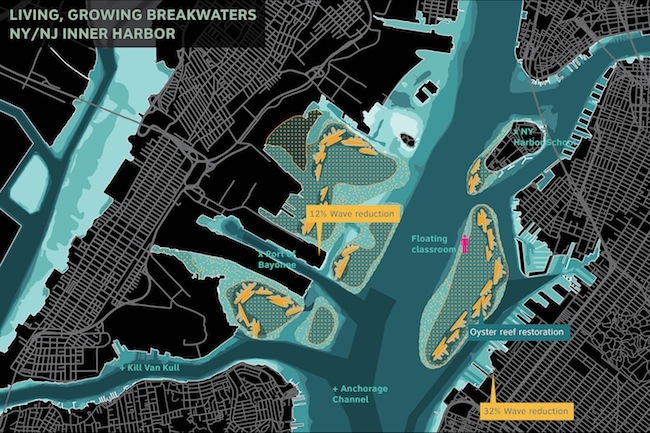

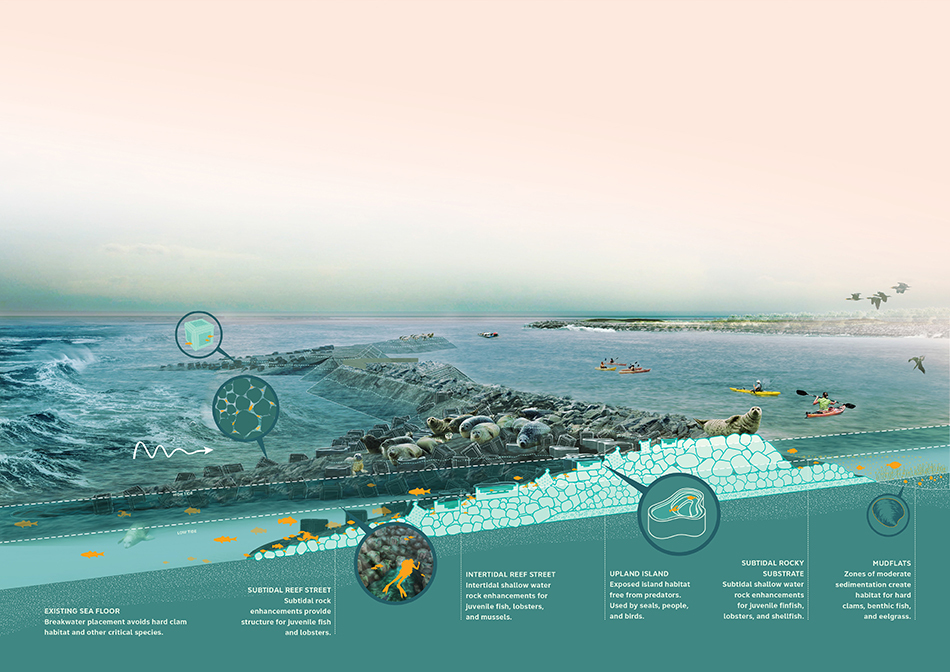

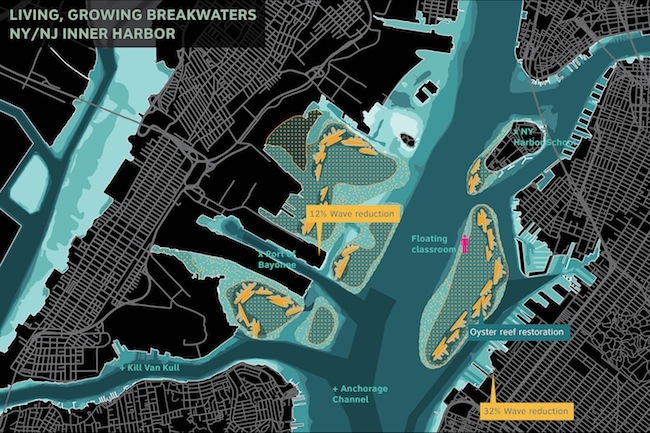

Images © Scape / Landscape Architecture

Living Breakwaters

Scape / Landscape Architecture

Scape developed Living Breakwaters, a proposal that also features physical barriers (“a necklace of breakwaters”) as a method for long-term, sustainable protection for both the city and the environment on which it depends. Breakwaters made from piles of rock are arranged in a specific way in each site, sometimes coming above the water line and sometimes lying just below.

This proposal is in line with current practices, as breakwaters have been used for decades as a man-made barrier to beach erosion. Scape, however, takes the ecological component to the next level by designing areas of the breakwater as “micro-pockets of habitat complexity to host finfish, shellfish, and lobsters”. in Rebuild by Design, Scape builds on their previous experience in the Rising Tides competition, in which the term “Oystertecture” was cleverly coined. This time, the term of choice (for those habitat micro-pockets) is called “Reef Street.”

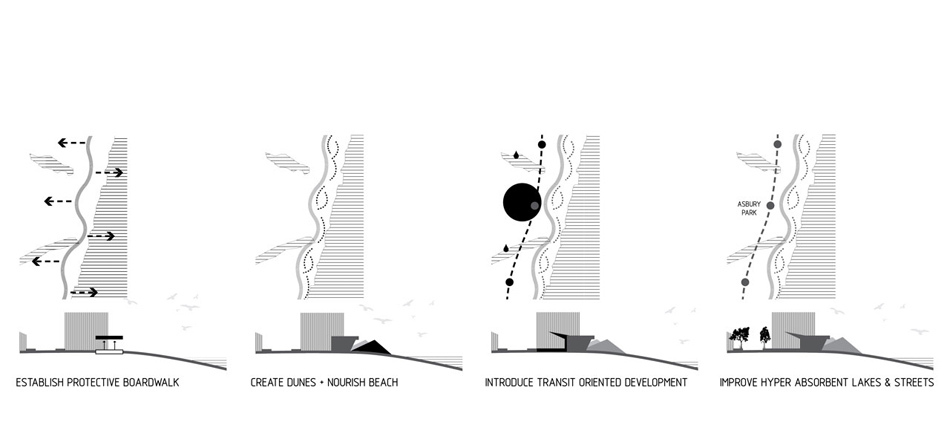

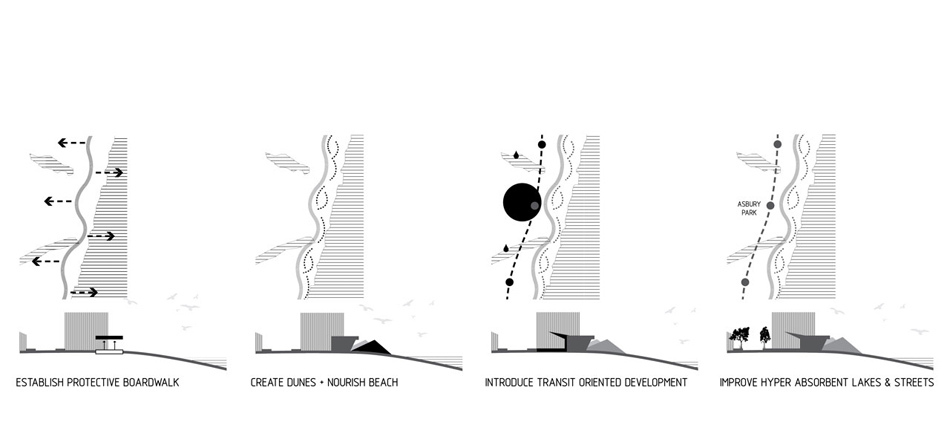

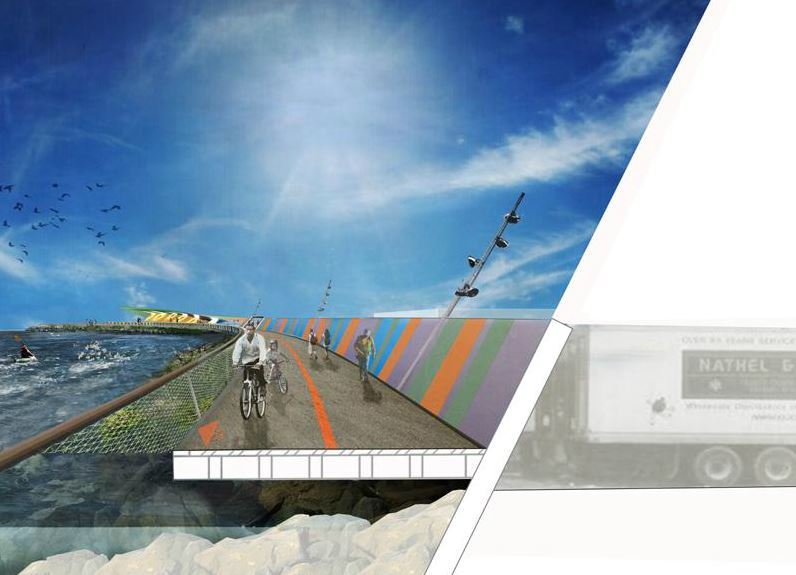

Images © Sasaki / Rutgers / Arup

Images © Sasaki / Rutgers / Arup

Resilience + The Beach

Sasaki / Rutgers / Arup

Nowhere is the concept of “the beach” as a cultural element more important than in the famous/infamous Jersey shore. Sasaki, along with Rutgers and Arup, focuses on the concept of the beach not only as a cultural icon, but an important focal point of economic, social, and environmental systems. In their analysis, the definition of the beach is expanded to include three coastal typologies: Barrier Islands, Headlands, and the Inland Bay. It’s this broadening of geographic scope that Sasaki believes will “deepen the physical extent, ecological reach, and cultural understanding of the beach.” Within each of these defined typologies, the design team has selected three project areas as case studies, allowing the project to maintain geographic specificity yet applicability to any other site within the same ecological zone.

Sasaki’s proposal is incredibly wide-ranging; it almost seems as if they’ve combined three proposals into one. However, rather than approaching the project as a planning exercise from 10,000-feet above the ground, they’ve decided to focus in on the details as well. My favorite example of this is the dual-purpose boardwalk, in which “two different boardwalk conditions are explored – the civic core and the experimental zone.” This experimental boardwalk, rather than built to hover above the sand, merges with the ground itself, even aiding in future dune creation. The boardwalk itself curves and angles along the surface of the sand like a covering, adapting itself to the irregular surface. This dune creation allows for the protection of inland elements as well as aiding in habitat creation for birds and wildlife.

Images © PennDesign / OLIN

Hunts Point Lifelines

Penn Design / OLIN

While Scape and West8 focused their efforts on the physical construction of barrier islands in various forms, Olin takes a systematic approach to forming a “working model of social, economic, and physical resilience.”

Coastal resilience isn’t just about keeping the water out at all costs. It’s also about what you do when your designed system fails, and how an entire community can remain resilient in the meantime.

OLIN’s proposal tackles this problem by not only providing physical storm barriers and seawalls to keep the water out, but also allows room for infrastructure that operate in contingency situations. One example of this infrastructure includes “maritime emergency supply lines” that keep supplies flowing through a system of piers that can run even if other methods of transport are closed. The other three proposed “lifelines” involve economic incubators, energy producers, and flood barriers.

While less focused than other proposals, OLIN’s multi-faceted solution is no less developed. In their view, a systemic problem calls for a systemic solution. The “WORKING WATERFRONT + WORKING COMMUNITY + WORKING ECOLOGY” concept provides just that.

What do you think of these project proposals?

Read More:

Lead Image © Scape / Landscape Architecture