Article by Paul McAtomney – We take a moment to consider 10 things that need to be considered in ecological planning and design. The forces of current global conditions hovering over the human race today—population densification and growth, unbridled urbanization, changing climatic conditions, food production, and biodiversity loss to name but a few, alter ecosystems and cause environmental damage from the local to the global. To address these conditions, many landscape architects are shifting to a more systems-based and ecologically-driven approach to the design of the contemporary landscape. For those unversed in ecological planning and design, here are 10 things to consider.

Ecological Urbanism. Get it HERE!

Ecological Planning & Design

1. Ecological Context

As with any piece of design, context is everything. All design problems and interventions are embedded in and must respond to a wider ecological (and cultural) context, and a rich understanding of these factors is critical. How is the design integrated with a site or region’s soils, flora and fauna, materials, culture, climate, and topography? In the article, Ecological Urbanism: a Framework for the Design of Resilient Cities, landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn reaffrims this by proposing that site boundaries and scope of work need to ultimately be expanded in order to address the challenges posed by site, program, and context.

2. Scale Linking

The scale and scope of ecology extends far beyond the limits of the urban terrain. To facilitate connections between contexts, ecological designers need to scale-link. Often we only register relationships or processes at a single scale. But as ecological design stalwart Sim Van der Ryn acknowledges, all design activities have impacts far beyond perceived scales and political jurisdictions. What is critical is for the landscape architect / urban designer to understand the scales at which a system operates or at least which processes and disturbances are occurring.

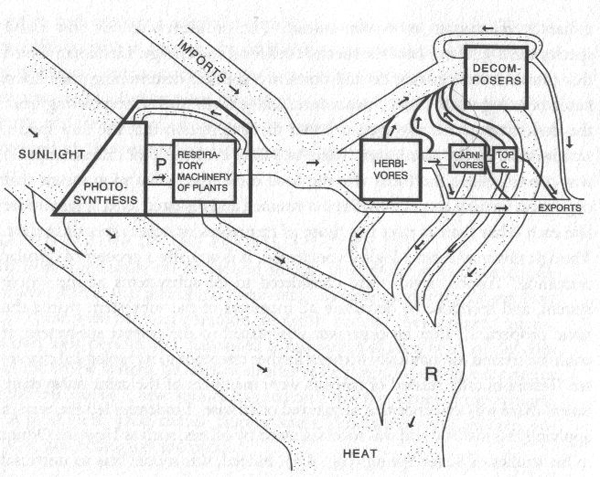

3. Systems Hierarchy and Flow

How do we make sense of systems? We catalogue them—give them hierarchy and a relationship to one another. For example, is the system in question open or closed? Natural or built? This cataloguing of systems allows us to view and understand our milieu as made up of a series of integrated, overlapping networks, making it easier to comprehend the complexity of landscape processes to which a site is connected and track flows across the landscape.

H. T. Odum, Energy and Matter Flows Through an Ecosystem. Model adapted from his 1957 study of Silver Springs, Florida. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

4. Green Infrastructure

Green Infrastructure (GI), such as performative parks, urban forests, and drainage corridors, down to green roofs, for example, has emerged as a concept to describe the spatial integration of natural systems and networks with hybrid infrastructures or built landscape systems. By considering key ecological principles of scale linking, hierarchy, and process relationship, designers are able to reduce the burden on traditional grey infrastructure systems and concurrently provide a plethora of environmental and social benefits.

The SW 12th Avenue Green Street © City of Portland, courtesy Bureau of Environmental Services

5. Ecosystem Services

From GI we secure the provision of ecosystem services—benefits derived from nature in urban and human-dominated landscapes. Frederick Steiner, the Dean for the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, suggests these services can be direct—air, minerals, food, water, and energy etc.; regulatory—water purification, carbon sequestration, climate mitigation, pest and disease control etc.; or cultural—intellectual inspiration, recreation, eco-tourism, scientific discovery, and so on. Turenscape’s landscape architects applied ecosystem service metrics to the design of Qunli Stormwater Park, combining recreational use with aquifer recharge and native habitat protection.

Qunli Stormwater Park. Photo credit: Turenscape

6. Natural Disasters

Every city and settlement is prone to specific natural and human-induced disasters. Green and landscape infrastructure systems offer potential to ameliorate the impacts and aftermath of disasters and hazards. Human settlement has always gravitated to and expanded upon areas of high ecological constraint such as floodplains and coastlines, with settlement decisions often at odds with the natural systems they are embedded in. The critical question is how can we adapt to these catastrophes, and even exploit them?

7. Ephemerality / Permanence

Designers are in general trained to imagine or choose a future state for a site and design it accordingly. The multiple possible operating states of ecosystems, however, illuminates that not all features of the landscape are equal—some are enduring, others temporal. To anticipate and design for change and ephemerality is to design ecologically—what Nina Marie Lister calls adaptive ecological design, design that “demands adaptability, [and] is predicated on resilience”. Lister puts this into perspective by considering many of today’s designed landscapes that require copious economic and ecological inputs to remain in constancy, but which are rarely designed to absorb and adapt to short-term disturbances or long-term ecosystem transformations.

Boreal forest one year (left) and two years (right) after a wildfire. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

8. Transdisciplinarity

By its very nature, ecological design is transdisciplinary, stretching across a plethora of disciplinary boundaries in order to formulate new concepts and theories. Many of today’s ecological design problems bridge conventional scientific and design disciplines. Yet, all too often, design and planning processes remain routine and homogenous. In his book Ecological Design, Sim Van der Ryn suggests that only if artists talk to scientists, writers to designers, engineers to biologists, architects to physicists, farmers to ecologists, and so on, can the blend of ecology and design continue to be forged.

9. Nature / Culture

Cultures are manifestations of design, or at least, of the intentional shaping or manipulation of our landscapes. Modern industrial societies, however, have collectively denied the nature / culture interface, viewing them as opposed. This false division has led to design ideologies that narrowly cater to human interest, often at the cost of environmental, cultural, and social values. Ecological planning and design offers a potent means to (re)imagine (and re-discover) the relationship between nature and human culture that traditional place-derived societies once fostered.

By Fredi Bach from Switzerland – Bir, India – XC Paragliding, CC BY 2.0, source.

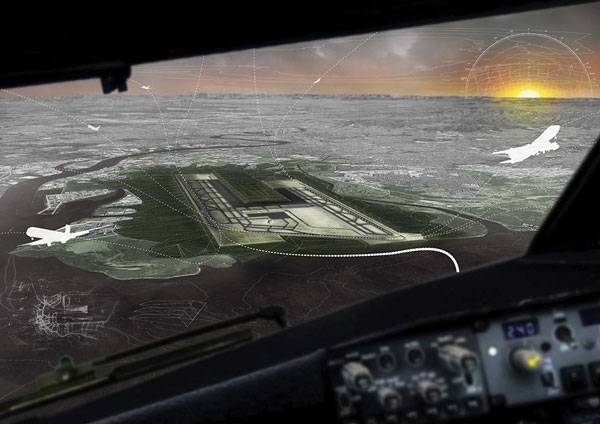

10. Speculation

Last, the importance of assuming a speculative posture when confronted with urban / ecological design problems cannot be overstated. In their book Ecological Urbanism, Mohsen Mostafavi and Gareth Doherty opine that “[t]oo often, environmental design is presented as a problem-solving agenda with moral/ethical ramifications, or with preconceived aesthetics that identify it as sustainable.” Speculations, however, yield creativity. An ecological approach is needed for many of today’s problems, but not one absent of imaginative and ductile design ideas that go beyond purely environmental concerns. Rather, speculative ecological design affords designers the chance to develop layered, flexible, and adaptive design responses that navigate the nexus of nature and culture.

Speculative project re-imaging the future of Brisbane Airport in Queensland, Australia. Image source: Paul McAtomney

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

Article by Paul McAtomney

Published in Blog