LA+, published by ORO Editions, started out in the spring of 2015 as a unique, landscape-focused journal that deviated from the pack by not only bringing designers, but philosophers, artists, geographers, ecologists, planners, scientists, and others to the table for their take on a core theme in each issue. Since then, the folks over at the UPenn School of Design have covered the themes of Wild, Pleasure, Tyranny, and Simulation. Along with the individual theme, each issue ends up with its own unique tone and perspective. This season’s issue is Identity.

The concept of identity shapes the very core of what we do as landscape architects. “Place-making” is often the seminal charge of clients and the means they use to create, reinforce, or change the identity of a place. This process pulls from every aspect of our skill set. LA+’s Spring Edition explores how the ideas of place have evolved and how “sense of place as the the manifestation of cultural identity has been landscape architecture’s raison d’être and its main aesthetic contribution to the cultural landscape of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

Not easing in, the editors start by literally comparing the landscapes of Nazi Germany to those “mass produced by today’s so-called ‘placemakers.’” Shots fired. The creative backlash against organizations like Project for Public Places is real and mentioned more and more often. What are we to make of manufactured identities? Is a 21st century programmed place any less authentic than one developed in centuries past?

The initial brushes of the Identity issue wax romantic on the notions of self and personal identity. It surmises that only through the lens of yourself, can you truly take the next logical step and consider a symbiotic relationship with your convenient planet of reference. This symbiotically connects the life and health of the planet directly to you and your actions. However, though these philosophical ruminations are clear and convincing, are they really arguments that need to be made to the intended audience? A philosophical understanding of our entire industry notwithstanding, the invocations of meaning are thoughtfully pondered, but for this reader, mostly end up in the same place they started.

A more interesting evolution of the symbiotic premise is then applied to the idea of colonizing other planets. If humans are currently in a thoroughly vetted, interdependent relationship with Earth, then how do humans sync up with worlds of different origins and inhospitable environments? Are we hopelessly confined to being but guests and never capable of the sort of congruence we have with our current home?

A brief and fascinating passage by Dirk Sijmons asserts that identity is, in fact, a verb, or more specifically, a process. He asserts that though in the past century, designers have clung to the idea that landscape form is just a creative output of the project constraints and an application of art, we forget to consider the massive importance of macro processes that shape space. In his example, the massive dam and weirs projects in Holland attest to human’s ability to shape and augment space to fit basic needs. Modern designers have used remnants and echoes of these forms to derive designs that supposedly echo the “genus of place.” Their assertion, however, under weighs the agricultural, industrial, and defensive motivations for the augmentation in the first place. The changing needs of inhabitants over centuries and their willingness to take on massive scale revolutions in the landscape are the true basis of identity. Consider the canals of Egypt, the rapidly spreading swaths of suburban China, the Hoover Dam of Nevada, or the artificial islands of Dubai where Sijmons asks if processes of civilization are the generators of identity, rather than social or colloquial elements landscape architects often use to derive form.

Further considering manufactured uniqueness, Andrew Graan and Aleksander Takovski mine Macedonia’s “Skopje 2014 for lessons in identity.” Skopje 2014 is an extraordinary architectural makeover project in the namesake capital city of Macedonia that seeks to clear asunder the remnants of Ottoman and Socialist markers that unfortunately results in a “sense that one has stumbled into a fantastic landscape that desperately wants to be noticed.” Skopje’s array of massive statues of Alexander the Great and others seeks to create a “political economy of architectural spectacle.” While the statues and buildings are derived from historical references and hit all the notes of place-derived focuses, the product borders on infatuation and excess. How are we to consider the identity of these places years, and even decades, from now? Will Skopje be viewed as an exercise in abject nationalism, or will it meld into the fabric of Macedonia’s identity causing future designers to derive their forms from it?

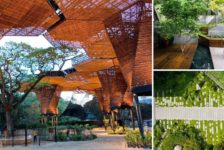

Finally, one of the most interesting reads from this issue is Branding Landscape by Nicole Porter. She asserts that ‘place’ itself has obvious intrinsic economic value and the strategic practice of ‘place branding’ seeks to exploit that value. Two case studies, Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay and Norway’s national park branding, outline her argument that these branded landscapes have been reduced to “functioning as commodified objects functioning as brands.” In both instances, the government harnesses the most cost effective way to impress and, consequently, express the commitment and efficiency of said government. She laments that “the irony is that producing place identities according to market-friendly typologies can destroy their true uniqueness and inherent value at the same time.” Her worry is that a capitalist ideology injected into the human-nature relationship is a slippery slope that forces everyone to be consumers.

LA+ Identity is another excellent entry into an already thoughtful collection of varied perspectives on the work that landscape architects do. While some of the more existential explorations of philosophy are valuable and necessary, the critique of pervasive ideologies and popular landscapes is even more essential.

—

Benjamin Boyd is a landscape architect practicing at Mahan Rykiel Associates in Baltimore, Maryland. Check out his profile on Goodreads to see what he has been reading. Ben often tweets about landscape at @_benboyd.