Article by Terka Acton – We take a closer look at one of Europe’s most major cities and ask the question “Why Make London the First National Park City?”. London is famously one of the world’s most crowded and frenetic cities, so it may come as a surprise that there is a growing movement to make it the first ever National Park City. In fact, the city’s habitat is startlingly diverse: More than 8 million humans co-exist with 13,000 species of wildlife living in 3,000 parks, 30,000 allotments and community gardens, 36 sites of special scientific interest, and 142 nature reserves, as well as in wasteland and the 3.8 million gardens that cover 24 percent of the capital. In total, 47 percent of London is green space.

Bees and lavender, Westminster. Credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative

So What is a National Park City?

The campaign prospectus defines a National Park City as “a large urban area that is managed and semi-protected through both formal and informal means to enhance the natural capital of its living landscape. A defining feature is the widespread and significant commitment of residents, visitors, and decision-makers to allow natural processes to provide a foundation for a better quality of life for wildlife and people.” It’s just an idea at present, but one that could offer a model for cities all over the world.

Green Wall at Edgeware Road. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

There are 15 national parks in the United Kingdom, covering a diverse range of terrain, from coastal areas to moors and mountains. What’s missing is a major urban habitat, argues Great London National Park City campaigner Daniel Raven-Ellison. National parks, first designated in the UK in the 1950s, have a statutory duty to “

conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife, and cultural heritage of the area” and “

promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of the park by the public.” While these ideas can usefully be applied to the idea of London as a National Park City, campaigners stress that there are no plans to change planning policy in the capital.

Moo Canoes + Canary Wharf. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

London has a long history of protecting its green space. From the royal parks created in late medieval times to the public park movement in the 19th century, the garden city suburbs of the early 20th century, the designation of the green belt in the 1950s, and the nature reserves established in recent decades, much of London’s green space is already protected through planning legislation. Funding for these spaces is not protected, though, and the impact of cuts to parks budgets is significant. A parliamentary committee is currently considering whether London’s parks should become a statutory service — that is, one that legally must be supplied by the authority concerned.

Green Roof + Bee Keeping in the City. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Green Infrastructure

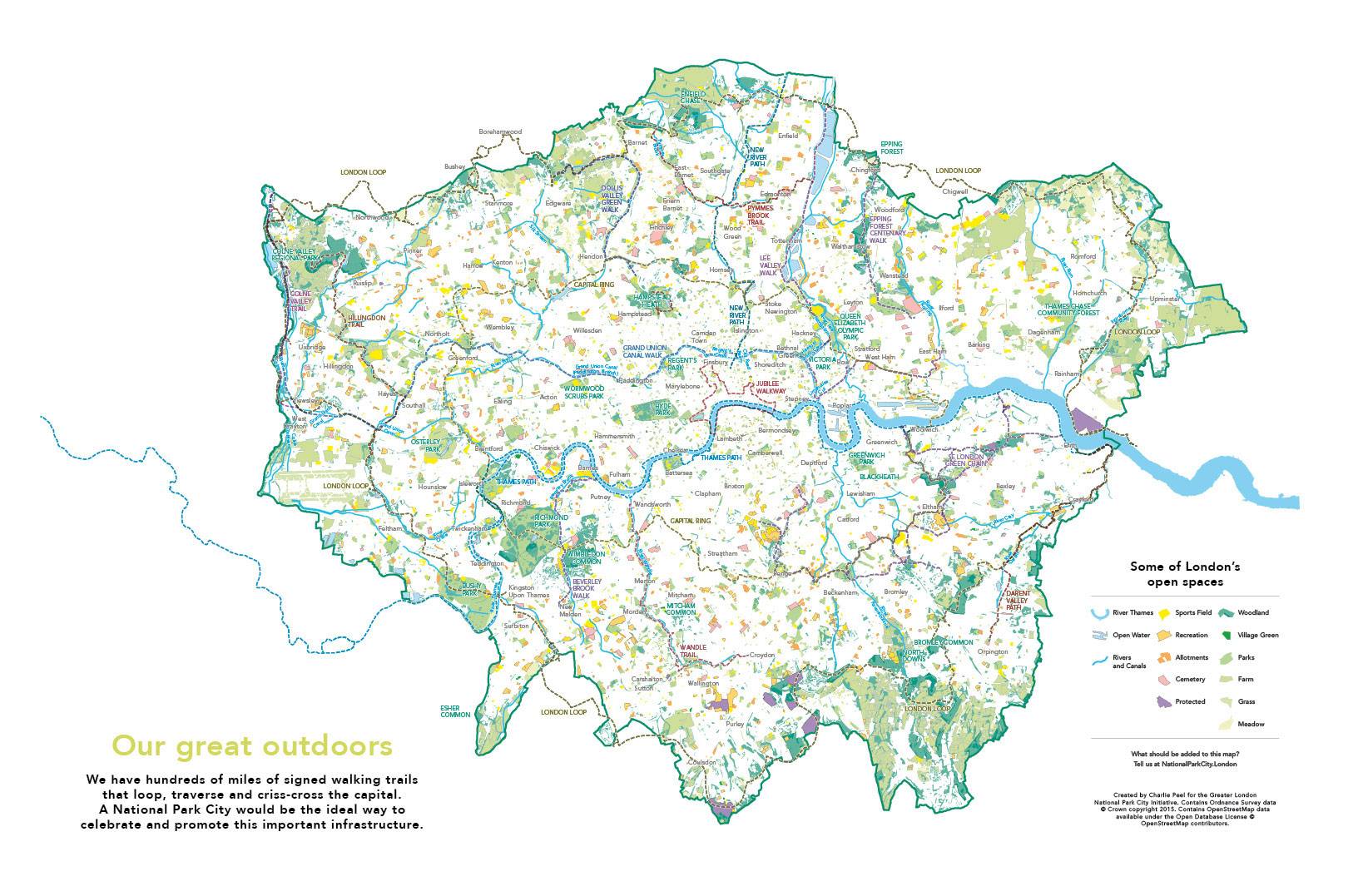

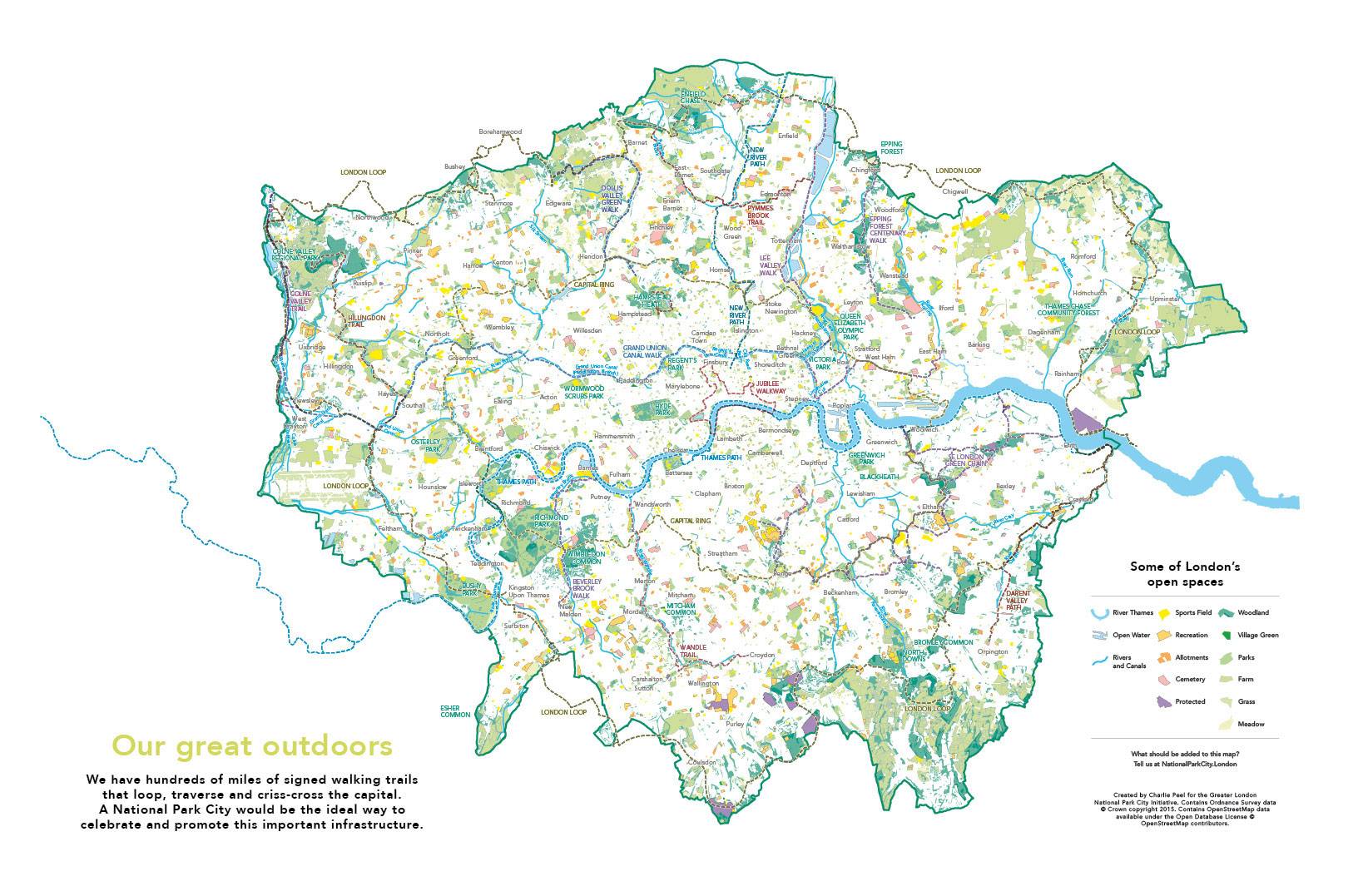

Parks are just one element of London’s green infrastructure network, however, and state funding is only one part of the support that it can draw on. While green spaces certainly merit governmental support, supplementary resources need to come from a wide range of public, private, organizational, and voluntary sources. While the National Park City would not have the additional planning powers accorded to the existing national parks, it would work closely with the many organizations and groups, often community-led, that are already greening the capital.

Stag beetle. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

designation would overlay these foundations, drawing together and supporting these existing threads in a way that that makes sense in the context of green infrastructure – that is, the network of natural features, green spaces, rivers, and lakes that intersperses and connects the gray infrastructure of our landscapes.

GLNP Map. Image credit: Charlie Peel. Click to enlarge

It is the wildest parts of that network that have perhaps the greatest potential for re-invention and re-imagining – the railway embankments, brownfield sites, wastelands, and edging strips that are home to communities of plants, insects, and animals.

Thomas Rainer and

Nigel Dunnett are among those in the forefront of global trends in planting design that encourage us to work with urban spaces in a way that takes inspiration from nature’s ability to adapt to our post-wild world – an ecological approach to landscape design that is completely in tune with a vision of cities as national parks.

Looking toward Wembley from North London. Credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative

The brilliance of the Greater London National Park City concept is that it sees the city as one living entity, embracing all of London’s green and blue space. It extends the values of traditional national parks to the urban context, emphasizing the importance of London’s natural spaces and how they co-exist with the built environment. It is a truly grassroots movement, as the prospectus notes: “

All kinds of people are involved: cyclists, scientists, tree climbers, teachers, students, pensioners, unemployed, under-employed, doctors, swimmers, gardeners, artists, walkers, kayakers, activists, wildlife watchers, politicians, children, parents, and grandparents.”

Deer & Cyclist in Richmond. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

feels that by placing an emphasis on working with schools and communities, the culture will gradually shift in many small ways, so that fewer front gardens are paved over, more trees are planted, and volunteering to protect our natural heritage becomes a bigger part of our culture.

London architect Sir Terry Farrell describes it as “

one vision to inspire a million projects.” Supported by more than 100 social and environmental organizations, the proposal has been widely taken up by policy makers: It received a vote of confidence from the London Assembly in 2015, and London’s Mayor, Sadiq Khan, has pledged that he “

will make London a National Park City.”

Deer in Richmond Park. Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Raven-Ellison is targeting London’s wards (the smallest political unit), reasoning that once two-thirds of the 654 wards and the mayor have all declared their support, London will have the mandate to call itself a National Park City. So far, Raven-Ellison tells me, 211 wards have signed up, representing more than 30 percent of the target.

Ideas Into Action

Proponents emphasise that the designation will contribute to London’s prosperity by encouraging the co-existence of ecosystems and biodiversity; providing physical and mental health benefits; boosting inclusion, diversity, and creativity; shaping behavior in ways that will help the city reach its decarbonization targets; and easing environmental problems such as air quality and flooding.

Duck in Camden. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

, urban greening team leader for the Greater London Authority, estimates that London’s population could reach 13 million by 2050. Massini argued at the Making of a National Park City event held in London this September that National Park City status would help make greening policies already in the pipeline “more relevant” and help London to meet the growing need for green space and urban regeneration as the population increases.

Swimmer Hampstead. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

While some argue that this initiative could result in nothing more than a new tier of bureaucracy, and while it’s true that the details of funding are not yet fully worked out, a London-wide approach could be the starting point of a new pressure group to connect and amplify the voices of charities, groups, and officials already working on public green space and could change the way people see the city’s networks of streets, gardens, parks, and wild spaces.

Going Global

The Greater London Park City initiative offers a chance to reimagine our definitions of both cities and parks around the world, and to encourage all of us to think differently about our cities. I would be proud to live in a National Park City – would you?

CLICK TO COMMENT

Recommended Reading:

Article by Terka Acton

Published in Blog

Pingback: Why make London the first National Park City? - terka acton