Author: Ofer Cohen

Why Make London the First National Park City?

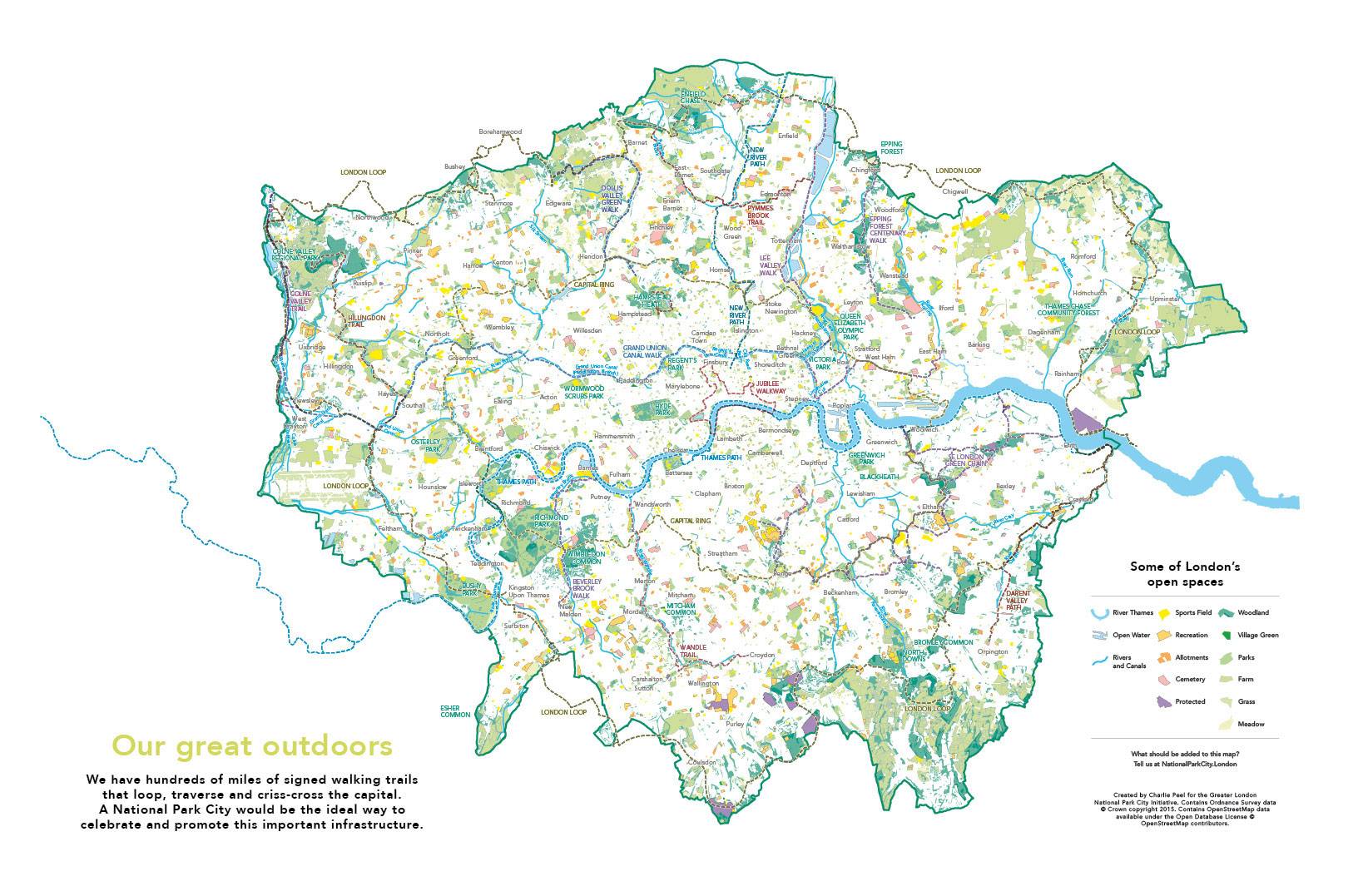

Article by Terka Acton – We take a closer look at one of Europe’s most major cities and ask the question “Why Make London the First National Park City?”. London is famously one of the world’s most crowded and frenetic cities, so it may come as a surprise that there is a growing movement to make it the first ever National Park City. In fact, the city’s habitat is startlingly diverse: More than 8 million humans co-exist with 13,000 species of wildlife living in 3,000 parks, 30,000 allotments and community gardens, 36 sites of special scientific interest, and 142 nature reserves, as well as in wasteland and the 3.8 million gardens that cover 24 percent of the capital. In total, 47 percent of London is green space.

Bees and lavender, Westminster. Credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative

So What is a National Park City?

The campaign prospectus defines a National Park City as “a large urban area that is managed and semi-protected through both formal and informal means to enhance the natural capital of its living landscape. A defining feature is the widespread and significant commitment of residents, visitors, and decision-makers to allow natural processes to provide a foundation for a better quality of life for wildlife and people.” It’s just an idea at present, but one that could offer a model for cities all over the world.

Green Wall at Edgeware Road. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Moo Canoes + Canary Wharf. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Green Roof + Bee Keeping in the City. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Green Infrastructure

Parks are just one element of London’s green infrastructure network, however, and state funding is only one part of the support that it can draw on. While green spaces certainly merit governmental support, supplementary resources need to come from a wide range of public, private, organizational, and voluntary sources. While the National Park City would not have the additional planning powers accorded to the existing national parks, it would work closely with the many organizations and groups, often community-led, that are already greening the capital.

Stag beetle. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Looking toward Wembley from North London. Credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative

Deer & Cyclist in Richmond. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Deer in Richmond Park. Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Ideas Into Action

Proponents emphasise that the designation will contribute to London’s prosperity by encouraging the co-existence of ecosystems and biodiversity; providing physical and mental health benefits; boosting inclusion, diversity, and creativity; shaping behavior in ways that will help the city reach its decarbonization targets; and easing environmental problems such as air quality and flooding.

Duck in Camden. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Swimmer Hampstead. Photo credit: Luke Massey and Greater London National Park Initiative.

Going Global

The Greater London Park City initiative offers a chance to reimagine our definitions of both cities and parks around the world, and to encourage all of us to think differently about our cities. I would be proud to live in a National Park City – would you?

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

Article by Terka Acton

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities – 10 Ways Green Roofs Can Help

Article by Terka Acton We explore 10 brilliant projects and how they produced green roofs for healthy cities Picture a healthy city. What does it look and feel like? Odds are that you’re thinking of somewhere bustling with commerce, education, and events – but also somewhere that’s cool and clean, with fresh air, attractive architecture, and public spaces that are green, open, and inviting to all. If this is your vision, your instincts are accurate – and green roofs have become an important part of the strategy for achieving cities that include all of these elements. As well as protecting buildings and adding character to the urban environment, green roofs can help to manage rainfall and create diverse new habitats for plants, wildlife, and people. And as we face a future with fewer wild, open spaces, we look to the use of green roofs in our cities as a way of addressing the serious issues of excess stormwater, the urban heat island effect, and soil sealing. To download our eBook on Green Roof Construction join the Landscape Architects Network VIP Club by clicking HERE!

Get Green Roof Construction: The Essential Guide, by signing up to our VIP Club HERE!

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Green roofs help to cool urban environments, improve air quality, and provide biodiverse habitats for wildlife. They manage rainwater by reducing run-off and filtering out pollutants. Importantly, they can also add usable space. Green roofs can also insulate buildings, reducing heating and cooling costs — this is how they can help mitigate the urban heat island effect, which occurs when the heat generated by buildings raises the temperature of their surroundings. With so many benefits, it is not surprising that the inclusion of green roofs can help with gaining planning consent.

So What is a Green Roof?

There are many variations on this theme, but, in general, a green roof is an extension of an existing roof that involves a waterproofing and root-repellent system, a drainage system, filter cloth, a lightweight growing medium, and plants. Green roof systems may be modular — with drainage layers, filter cloth, growing media, and plants supplied in movable grids — or built-up, with each component of the system installed separately. See Landscape Architect Network’s ebook Green Roof Construction: The Essential Guide for helpful details on all aspects of green roof construction.

Here are 10 Ways to Use Green Roofs for Healthy Cities :

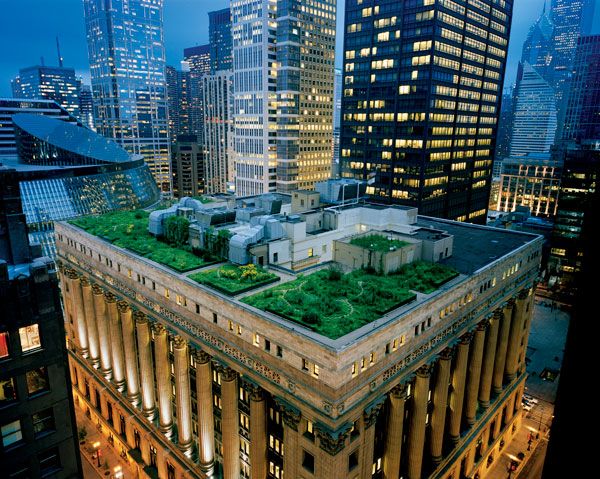

1. Chicago City Hall Green Roof, by Atelier Dreiseitl and Conservation Design Forum, Chicago, Illinois, USA It was the infamous urban heat island effect that compelled the city of Chicago to establish a green roof on City Hall. When a heat wave in 1995 killed several inner-city residents, the city fathers were keen to find a way to reduce the impact of the heat island effect. The green roof created for City Hall is formal and symmetrical, echoing the lines of the historical building, but it was not designed for public access. Instead, the design provides a pleasing view from above, with practical pavers for maintenance. Rose Buchan’s article details the creation of the Chicago City Hall Green Roof and its significance: This project has contributed to the establishment of Chicago’s Green Roof Initiative, which has resulted in more than 200 other living roofs being planted all over the city.

2. The Rooftop Park at Saint John’s Bulwark, by OSLO Ontwerp Stedelijke en Landschappelijke Omgeving, in `s-Hertogenbosch (Den Bosch), The Netherlands The Rooftop Park at Saint John’s Bulwark addresses another threat to the creation of healthy cities: flooding. The city of `s-Hertogenbosch addressed the problem by restoring the 6.5 kilometers of walls that surround the city, making them more effective against floodwaters from the Aa and Dommel rivers. Saint John’s Bulwark is just one of the more than 80 projects involved in this restoration. The rooftop pocket park, the focus of this article by Erin Monk Tharp, incorporates Cor-Ten steel planters to give the planting depth required for the honey locust trees (Gleditsia triacanthos) used to shade the park. Concrete paving tiles retain the gravel that allows the free drainage of rainwater into the rubble substrate, from where it can be stored to water the plantings of carex grasses. This rooftop park protects the city against flooding, provides a beautiful green space for recreation and ecology, and preserves the heritage of the space. In sum, this project is a great contribution to the cause of using green roofs for healthy cities. 3. American Society of Landscape Architects’ headquarters, by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc. and Conservation Design Forum, in Washington, D.C., USA Healthy cities are diverse, not just in their mix of people and functions, but also in terms of biodiversity. This is the guiding force behind ASLA’s green roof project: It seeks to demonstrate the environmental benefits of green roofs and monitors the success of a number of plant species in order to identify a diverse palette of plants that can survive with minimal maintenance on urban rooftops. This innovative scheme is covered in more detail by Agmarie Calderon Alonso in this piece, which describes how the use of Styrofoam and waves of planting minimizes the weight of the structure, allows for a variety of testing environments, and improves the performance of the building. During the winter, the insulation provided by the roof decreases heating costs by 10 percent. Plants include native perennials such as purple love grass (Eragrostis spectabilis) and butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) on the north side, while on the south side prickly pear cactus (Opuntia sp.) and other succulents are featured. As green roofs become more widely used, we need initiatives such as ASLA’s green roof project to increase the diversity of the plants we use, thereby protecting the environment, improving the health of cities, and pushing the boundaries of what is possible, as landscape architects, in terms of using green roofs for healthy cities. 4. The Roof Gardens of the European Patent Office, by Copijn Tuin-en Landschapsarchitecten, Rijswijk, The Netherlands The European Patent Office plans to replace its current building, feeling that the cuboid, 1970s architecture no longer meets the needs of the organization. But the roof garden currently covering the car park and an extension to the main building will be retained. Designed in the 1990s, it has stood the test of time and will be integrated into the new building. The brief was to introduce natural elements into the site and to provide an outdoor space for the benefit of employees — both of prime importance when it comes to the building of healthy cities. The roof garden also harvests and stores rainwater. The layout and planting are designed to represent the Dutch landscape, with dikes and valleys planted with native and near native species. Ashley Penn’s article explains how the organic, curvilinear forms of the roof garden offset the brutalism of the architecture of the EPO building, showing another way in which green roofs can be used to improve urban environments. 5. Delft University of Technology, by Mecanoo Architecten, in Delft, The Netherlands Delft University of Technology’s library, constructed in 1997, was designed on a sloped plane. The grass that covers it extends from the ground to the edge of the building roof, and it’s possible to walk all over the roof. The library is topped by a steel cone, and the walls are glass. Underground, 15,000 square meters of archives, reading rooms, and study spaces cater to the needs of university students, staff, and visitors. As Win Phyo’s article explains, the densely planted grass roof of the library offers the usual green roof benefits of insulation and rainwater harvesting, and the fact that the entire roof surface can be accessed by the public makes it a much-used amenity for the whole campus. A final benefit, especially useful for a library: The green roof is an excellent form of soundproofing! This clever design offers one way to make the best use of limited available space. 6. Funen Blok K, by NL Architects, in Amsterdam, The Netherlands Healthy cities need healthy buildings — developments created to be sustainable and liveable, and that integrate access to green space into their fabric. Funen Blok K in Amsterdam, by NL Architects, exemplifies this approach. This development was designed to maximize the experience of the landscape and its relation to the community. Part of the Funen Park Development, Funen Blok K sits on a former industrial site on the outskirts of Amsterdam’s city center. Unusually for The Netherlands, the area around the residential buildings is treated as one continuous courtyard. There are no private gardens. The design consists of three key elements: grass, paving, and a scattering of trees. This allows residents to flow freely through the landscape without feeling overwhelmed. Specially designed pentagonal concrete pavers in shades of gray delineate paths and create interest. The roof of the building is comprised of 50 percent greenery (sedum mix). The other 50 percent is devoted to terraces that allow each housing unit to access the roof. The rooftop undulates to allow the penetration of natural light. Nick Shannon argues in this article that the green roof gives this building a unique identity, adding value to the units and creating a place where people want to live. Not a bad benefit to add to the other environmental and cost-saving benefits of green roofs. 7. Roofpark Vierhavenstrip, by Buro Sant en Co with the municipality of Rotterdam, in Rotterdam, The Netherlands Roofpark Vierhavenstrip, the largest roof park in Europe, was completed in 2013. Built above a retail complex, it includes themed gardens, play areas, and community growing spaces, as well as a dike to help protect the city against floods. The community growing space is interesting, as it links with global efforts to growing vegetables, fruit, and herbs in the city: See this article for more on the environment and social benefits of edible planting in the city. This 80,000-square-meter public space helps Rotterdam to be a greener and therefore healthier city, with no loss of retail space. In addition to the well-known benefits green roofs bring, this project meets the needs both for a new urban park and for the growth of enterprise in the city, thereby improving the overall quality of life in the district. Ruth Coman’s article offers more detail on what this project can teach us about using roof gardens to overcome the limitations of a site, creating solutions for healthy cities. 8. Nouvelle at Natick, by Martha Schwartz Partners, Natick, Massachussetts, USA The Nouvelle at Natick development was initiated by General Growth Properties and incorporates the prize-winning 34,850-square-foot Parc Nouvelle roof garden, which was designed by Martha Schwartz and completed in 2008. The rooftop deck of the residences, located at the sixth-floor level, was designed to be experienced both directly — as one walks through the space — and from the apartments above, which look down on the clear, graphic shapes. The rooftop functions as a social space, connecting the residences and encouraging interaction among neighbors. A curvilinear, composite wood path links seating and planting areas, and deciduous trees provide shelter, shade, and vertical interest. The rich orange Cor-Ten steel of the large planters contrasts with the planting combinations of ornamental grasses, flowering perennials, and evergreen shrubs. Stone and sedum ribbons curve around the scheme, and further interest is provided by circular crushed-glass fountains. Two large grass circles serve as putting greens. See here for more detail on the project. Together, the rooftop decks provide for social connectivity among the residents, opportunities for relaxation, and an engaging visual experience. 9. Terrazas Reforma 412, by dlc Architects, Mexico City, Mexico As the largest metropolitan area in the western hemisphere, Mexico City is no stranger to the skyscraper. One of these — Tower Reforma Diana — is especially worthy of special mention in the context of green roofs. Completed in 2013, it includes several stunning rooftop gardens that feature composite wood and extensive planting. The composite wood is largely bamboo-plastic composite (BPC), and it is used to form furniture, planters, wall panels, and floor surfaces. Containing 60 percent bamboo fiber and 40 percent polyvinyl chloride (pvc), it offers a longer service life and lower maintenance than wood. While some urban green roofs offer viewpoints over the city scene, this rooftop has been designed as protection against the urban center’s noisy sprawl: The views consist of either a living wall or, above, the blue Mexican sky. As Sophie Thiel notes, the plant palette is limited to native species and includes many drought-tolerant succulents, perennials, and shrubs. There is a 100 percent reuse of rainwater through recycling, as well as an automatic irrigation system with sensors. Preserving scarce resources will ensure that we can create healthy cites not just now, but also in the future 10. Dakparken Anton and Gerard at Strijp S, by Buro Lubbers, in Eindhoven, The Netherlands Anton and Gerard are two industrial buildings on the former Philips industrial Strijp-S. In 2000, the redevelopment of the 27-hectare Strijp-S site began and, in 2009, the transformation of the rooftops as green open space for the inhabitants. This was completed in 2013, and the buildings are now topped by park-like spaces that offer stunning views over the city of Eindhoven. The concept of the parks was to create an artificial landscape that looked natural. Both parks combine pioneer planting with meandering paths and terraces, creating both shady, green outdoor rooms and sunny open spaces in order to facilitate a range of activities. Architecture and structural components are concealed in order to maximize the natural impression. They are, however, of the highest quality and designed with a 15-year lifespan in mind. A long-lasting drainage layer made up of a double-layered, 60mm-thick drainage mat was glued to the roof surface, and the planting substrate was designed to accommodate a range of plant types. Each garden responds to the specific architecture of the building on which it sits: The central planter on Gerard’s roof garden emphasizes Cor-Ten steel and birch trees, while a similar structure in Anton’s garden makes much use of timber and flowering plants. The project is not only a successful urban space, but an example of how landscape architecture can combine the natural and the artificial. See Rose Buchanan’s article for more detail on the way in which Lubbers has created this beautiful, high-tech landscape in the sky. Redeveloping brown field sites is an essential element in the creation of healthy cities – and doing this in a way that it sensitive to the site and to the needs of all those using the spaces is no less important.How Can These Projects Help Us to Use Green Roofs for Healthy Cities?

What is clear from this roundup of outstanding examples of using green roofs for healthy cities is that there is no excuse not to consider specifying green roofs, especially when dealing with urban environments. The benefits are huge, and the technology, methodology, and diversity of planting palettes have developed to the point where landscape architects have the tools and resources to create schemes in the air that are every bit as relevant, appropriate, and effective as those on the ground. Which urban green roof project do you most admire?

To download our eBook on Green Roof Construction join the Landscape Architects Network VIP Club by clicking HERE!

Article by Terka Acton

Can Urban Orchards Really Help Create Amazing Communities?

Article by Terka Acton Open Orchards are urban orchards, by the Open Orchard Project, London, United Kingdom. Urban greening is known to play a role in helping us deal with climate change, pollution, and temperature regulation. But – as this people-powered United Kingdom project is proving – making the most of the green spaces in our cities can also yield social benefits. Improving the local environment by planting urban orchards in public spaces can help to strengthen bonds within communities. The Open Orchard project started in 2014 in West Norwood, south London. With the help of funding from The Open Works, a group of residents came together to plant fruit trees in and around this built-up urban area. Fruit trees are a good choice for cities, since they can be grown on dwarfing rootstocks to make use of the smallest planting space and – once established – need little maintenance. …harnessed the power of social networks to ensure the project’s continuing success… This is the story of how the Open Orchard team got started, how it harnessed the power of social networks to ensure the project’s continuing success, and how it is helping to increase the number of community-led urban orchards so that everyone can share in the benefits that come from closer connections between people and the land.

Urban Orchards

What Can Urban Orchards Do for You?

Community orchards are a creative, sustainable solution to many urban ills, offering access to fresh fruit, benefiting city environments, and creating much-needed habitats for wildlife. For Open Orchard founder Wayne Trevor, however, the most important aspect of the project is the opportunity to facilitate connections. Connecting local residents so that they can create and look after urban orchards is a great way to link these city dwellers (most of whom don’t have a garden of their own) both to the land and to each other. “Children, especially, love to learn how to grow and harvest their own food” With growing concerns about the societal disenfranchisement that arises from economic inequality, common spaces that allow for social interaction, bonding, and volunteering are more important to our cities than ever. There is also a strong educational element: Children, especially, love to learn how to grow and harvest their own food. And harvesting is a key part of the plan. Some residents are concerned about the kind of issues raised in this LAN article by Taylor Stapleton: 5 Reasons Why Planting Fruit Trees Along Sidewalks is a Terrible Idea — until they are reassured that these trees, unlike street trees, will be grown in orchards and be cared for by members of the community.

Open Orchard #1: Norwood Bus Garage, south London. Photo credit: @Open Orchard

Apple “Kidd’s Orange Red” starting to color. Fruit trees are carefully chosen for each location. Most fruit trees need at least six hours of sun each day, although cooking varieties can cope with semi-shade. Photo credit: @Open Orchard

…6.3 billion people living in urban areas, according to the United Nations… By 2050, there will be 6.3 billion people living in urban areas, according to the United Nations, and the World Health Organization recommends that everyone should have access to green space within 300 meters of where they live. So we’re going to need more usable, shared green space – and it’s clear that urban orchards can help us to really benefit from every pocket of available land. Do you know of any potential urban orchard sites in your local area? Let us know in the comments below! Go to comments Learn more about The Open Orchard Project: Website: www.donaldsonandwarn.com.au Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

Article by Terka Acton Return to Homepage Featured Image: By Vladimir Menkov – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikipedia

Login

Lost Password

Register

Follow the steps to reset your password. It may be the same as your old one.