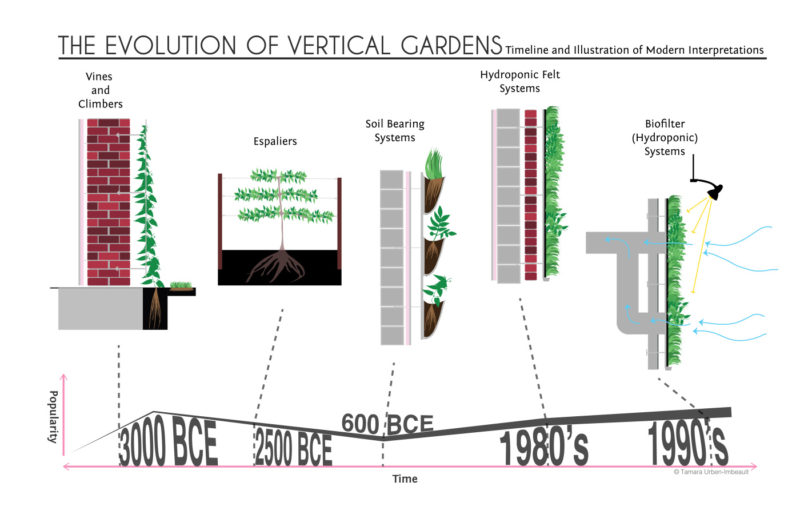

Vertical gardens have been growing in our cities and homes for centuries. The surge in vertical gardening technology in the 20th century has made this fact easy to forget. So, in case you’ve forgotten, or maybe you never knew, here is a brief history of the evolution of vertical gardening!

via Landscape Architect’s Pages, Image © Davis Landscape Architecture Ltd, London, UK

via Landscape Architect’s Pages, Image © Davis Landscape Architecture Ltd, London, UK

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WERE VINES

The first vertical gardens date back to 3000 BCE in the Mediterranean area. Grape vines (Vitis spp.) were, and continue to be, a very popular food crop for people in the region, so they were commonly grown in fields, homes, and gardens throughout the area. Sometimes vines were planted for the purpose of growing food, and others to simply provide shade in places where planting trees was not an option. Above is an example of Vitis vinifera that is being grown today in Greece.

University of Toronto’s Falconer Hall covered in Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) image © Tamara Urben-Imbeault

University of Toronto’s Falconer Hall covered in Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) image © Tamara Urben-Imbeault

In the last couple centuries, vine-based gardening has spread steadily throughout the world, aided largely by the Garden City Movement. The Garden City sought to integrate nature into the city, and because of the limited footprint needed for vertical gardens on grade, they quickly became an easy and fairly inexpensive way to green many cities. Species like Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), English Ivy (Hedera helix) and Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) are historically some of the most commonly planted vine species. Still widely used today, these plants are looked upon favorably for their ability to survive various climates and affix themselves to facades without the help of a trellis.

RELATED STORY: Vertical Gardens: A Brief Introduction

Although vertical gardening has existed throughout history, its modern-day popularity boom didn’t begin until the 1980s. In particular, German government incentives for city greening led to the creation of many vertical gardening projects, sparking further research into the living wall’s thermal benefits.

In 1987, leading German researcher Manfred Köhler wrote a thesis on vertical gardens’ thermal properties–how the green insulation layer cools buildings in the summer and retains heat in the winter–and it remains to this day a primary source on vertical gardening in colder climates. Köhler has since collaborated with researchers around the world, and has contributed to a famous German guide to vertical gardening: The Forschungsgesellschaft Landschaftsentwicklung Landschaftsbau (FLL) Richthimie für die Planning, Ausführing und Pflege von Fassadengegrüngen. It was first published in 1995, with a second edition published in 2000. Unfortunately, the guide is only available in German and it is unknown if the FLL has plans to translate it into any other languages.

Espaliered Pear Tree. image via Wikipedia

ESPALIERED TREES

The next incarnation of vertical gardening is known as Espalier. Espaliered trees became very popular in France in 2500 BCE and continue to be grown around the world today. Espaliers are usually fruit bearing trees, with apple and pear trees as the most commonly used species. The trees are tied to a wire framework or fence in order to train the young branches to grow into specific shapes (the process bears many similarities to the process undertaken to create a bonsai). They are grown in various patterns, the most popular of which are horizontal lines, 45° lines, and diamond shapes. The pattern shown above is known as Candelabra.

Mur Vegetal at the Taipeh Concert Hall, image © Patrick Blanc

Mur Vegetal at the Taipeh Concert Hall, image © Patrick Blanc

HYDROPONIC WALLS

Back in the 1980s, the world renowned French botanist Patrick Blanc began to experiment with his trademark hydroponic system, Mur Vegetale, which he has now applied to massive internationally-acclaimed green wall projects around the world. His first major project was completed in 1996, and he has since gone on to work with some of the most internationally recognized architects worldwide.

Blanc’s gardens are probably the most widely recognizable type of vertical garden by the general public. Amazingly, his lush creations subsist on a growing medium comprising just two thin sheets of felt, with a total thickness of only a couple millimeters. This means the system is relatively lightweight and soil-free. Because of the lack of soil, hydroponically-grown green walls are susceptible to fewer pests and fewer structural modifications are needed to accommodate the weight. Since the first installation of Mur Vegetale, many similar systems have turned up on the market.

University of Guelph’s Humber Campus Biowall. Designed by Nedlaw. image via Crossey Engineering Ltd.

University of Guelph’s Humber Campus Biowall. Designed by Nedlaw. image via Crossey Engineering Ltd.

BIOWALLS

In the 1990s, another interesting development in the technology of vertical gardening took place at the Guelph University’s Humber Campus in Toronto, where a team of researchers built and tested a hydroponic vertical garden that would double as a giant air filter. This research, initially funded by NASA, evolved into a company by the name of Nedlaw, which currently operates out of Ontario.

Vertical gardening is continuing to change and grow in the DIY community as well. Many popular projects involve re-using various materials like old eaves troughs, shipping pallets, and shoe organizers. These more DIY style vertical gardens will be covered in a future post in a few weeks.

Keep watching for the next post in Land8’s Vertical Gardening Series where we will explore “Vertical Gardens and the [Macro + Micro] Climate”!

Lead image © Tamara Urben-Imbeault

Written by Tamara Urben-Imbeault, M.L.Arch. student at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. She is currently working on her design thesis entitled “Vertical Gardening in Cold Weather Climates”

Contact: umurbeni[at]myumanitoba.ca or t.urbendesign[at]gmail.com

Sources:

Blanc, Patrick. (2008) The Vertical Garden From Nature To The City. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc.

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, GRHC (2010) Green Walls 101: Systems Overview and Design Second Edition Participant’s Manual. Green Roofs for Healthy Cities.

Hum, Ryan and Lai, Pearl (2007) Assessment of Biowalls: An Overview of Plant-and-Microbiral-based Indoor Air Purification System. Physical Plant Services, Queen’s University.

Nedlaw Living Walls Inc (2011). Living Walls – Green Walls. Retrieved from http://www.naturaire.com/

Prairie Public Television; PBS (2014). The Lost Gardens of Babylon Guide To Ancient Plants. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/uncategorized/the-lost-gardens-of-babylon-guide-to-ancient-plants/1176/

Peck SW, Callaghan C, Bass B, Kuhn ME. Research report: greenbacks from green roofs: forging a new industry in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC); 1999.

Published in Blog

![Equity, Justice, and Landscape [Webinar]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/HKOJ2017_kb-224x150.jpg)

Pingback: The historic origins of vertical gardens [gallery] - Grow Up

Pingback: Grow a vertical garden - a guide to creating a beautiful green wall

Pingback: An Introduction to Vertical Gardening

Pingback: Develop a vertical backyard – a information to creating a ravishing inexperienced wall – TAG Degree - Bonisa

Pingback: The amazing history of green infrastructure - greenscreen®