The following article is the first in a series of interviews with the recipients of the Scott Traveling Fellowship, a post-graduate fellowship awarded to students of the University of California, Berkeley´s Master of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning degree. The Scott Traveling Fellowship is completely open-ended, giving students the opportunity research a topic of their choice anywhere in the world.

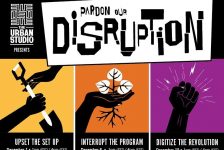

Image courtesy of Robert Tidmore and Alex Schuknecht.

When it comes to studying bicycle transportation, the field research is usually pretty simple. Look up some case studies, go out and do some bike counts, and maybe observe some field conditions and interview some cyclists. But if you’re Alex Schuknecht and Robert Tidmore of San Francisco, CA, that’s not going to cut it. For Alex and Rob, both landscape designers currently working in Berkeley, CA, the only way to study the bicycle infrastructure of a place is to cycle through it themselves – all of it. In June 2012, Alex and Rob flew from San Francisco to Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with their bikes in tow, and rode 5,500 miles (about 8,800km) from Ho Chi Minh City to New Delhi, India. You can learn more about their adventure on their blog: goodluckwiththetraffic.com.

DJ: You both biked over 5,000 miles in order to study the state of bicycle transportation in Asia, why such the long trip?

ALEX: One reason we had to make the tour this long was because we wanted to bike through a range of Asian cities, in order to see the parallels and challenges that all of them might be facing. We knew that finding the truth about the status of bicycle transportation meant that we needed the reality of first hand experience, so we drew a line on the map that took us through a lot of megacities, and that meant we had a lot of ground to cover.

But the main reason for the long trip is that it takes time to feel removed enough from your home to be truly immersed in your immediate surroundings. It takes about a month to even get your legs under you and your head in it, to where the days are less about the struggle and more about the now.

DJ: Give us a brief overview of your route.

ROB: We flew into Ho Chi Minh City at the end of June, right in the middle of the monsoon when the humidity basically becomes unbearable, and spent the next 2 months cursing our timing. From H.C.M.C. we biked south-west through the Mekong Delta and across Cambodia before reaching the superhighways of Bangkok. After a month biking across the crowded lowlands, we were overheated and craving altitude and solitude so we circled back east into southern Laos. We biked north for 3 weeks through Laos’ tortuous topography, before crossing back into Vietnam at the end of August. We left Hanoi in mid September, and pedaled north toward the Chinese border.

Alex in Southern Laos. Image courtesy of Robert Tidmore and Alex Schuknecht.

We biked north for 3 weeks through the urbanization and industrialization that is tearing up southern Yunnan Province, and after leaving Kunming we had our first and only taste of the good bike touring life: 4 glorious weeks biking up and across the Tibetan plateau, soaking up the Tibetan culture, getting dizzy at high altitudes and getting a much-needed break from urban insanity. Then we crossed our last pass in the Himalayas and descended 13,000 feet in one day, back down into the smog of Chengdu. Tibetan border closures forced us to break our journey after Chengdu and we packed up our bikes and gear and flew to Dhaka, which we’d decided we had to see for its half-a-million cycle rickshaws.

Rickshaws in Dhaka. Image courtesy of Robert Tidmore and Alex Schuknecht.

After the cold clean air of the Himalayas, the insane human density in Dhaka was intimidating but electrifying and we lingered longer than expected before heading west to Kolkata. On the highway to Varanasi, we came face to face with the dangers of Indian roads: a motorcyclist who had been hit by a truck literally died in my hands after we stopped to help him. From Varanasi, we moved west through Agra, paid our respects to the Taj Mahal, and biked into New Delhi, which was the last, largest and least fun city of the trip. Fitting.

DJ: So, what is the state of bicycle transportation in Asia? Is it different from country to country, from city to city?

ALEX: The thing we saw that all of these huge Asian cities have in common is that they’re all facing major problems with transportation, pollution, and public health.

In general I’d say the state of bicycle transportation in Asia is bad and getting worse. There’s poor urban planning and a sort of cultural aggression against cyclists that makes it seem like an insurmountable problem.

The Cuu Chien Binh cycling club. Image courtesy of Robert Tidmore and Alex Schuknecht.

Considering the obstacles though, there are so many stories of hope and possibility for change. Everywhere we went we found growing numbers of cycling groups, cycling advocates, bike shops and cycle tourism. The more visible and passionate these little micro-cultures become, the more hope there is that their cities will become livable and healthy, and of course the more hope we can have for the global environment. The future of Asian cities is obviously something we should all be very concerned with.

DJ: How is that different from how the United States embraces the bicycle?

ROB: In most of the places we cycled through, the bicycle was traditionally a tool. It was utilitarian, a way to move yourself and goods from here to there. The same can be said here at home. But for those who like to call themselves cyclists, I think the bicycle means a lot more.

Look at the explosion of fixed gears in a hilly city like San Francisco. They don’t necessarily make the most sense, but people ride them because they make a statement. Riding a bike, any bike, says you are aware of the larger implications of driving and you choose to do without. It’s strange that cycling has become a fad, but in my eyes anything that gets more people on bikes can’t be a bad thing.

Looking back, it might seem strange that we went to Asia to learn about bicycle culture and transportation when so much is being done right here in the Bay Area to promote and encourage cycling. But sometimes you need to leave home to recognize what you have.

DJ: Have your own bicycle habits changed since completing your trip?

ROB: Strangely, I think it’s made us both more reckless and more courteous. Once you’ve navigated the swarm of motorbikes in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi or weaved through insane traffic in Dhaka, Bangkok and Delhi, you get pretty confident. The traffic on Market Street appears tame in comparison. So I find myself taking more risks, swerving around cars in ways I wouldn’t have before.

On the other hand, we both now feel – more than ever – that we’re part of a larger global community of cyclists. And as representatives of this bike culture it’s important to leave drivers with a good impression of cyclists so that they respect their presence, and might actually want to be one of them. So we bike aggressively but we also try to bike more responsibly, especially around pedestrians.

DJ: In your opinion, what is the future of cycling in these [Asian] regions?

ALEX: In the long run, and on a long enough time scale, we’re all going back to the bike. I just don’t see any other way. The path some of these cities are on is so beyond sustainable it’s jaw-dropping. The traffic and pollution, from what we experienced, makes for an unsustainable quality of life. To some degree it’s quality of life that will move these urban cultures off the path of more and more drivers.

In most of the cities we visited, more and more people are driving because they can, and because the cycle of a growing economy encourages them to do so, because driving is consuming. A farmer in Thailand actually used that bit of wisdom to tell us that what we were doing was bad for his country. But there’s a growing contingent of passionate cyclists who do it because they believe in it.

Village cyclists in New Delhi. Image courtesy of Robert Tidmore and Alex Schuknecht.

Also, I’d say that the stigma of the poor cyclist – if you ride then you’re poor, and are therefore a lesser person – is starting to dissipate, and that makes me very hopeful.

The future of cycling depends on so many things, but the best we can hope for is that more people bike because they want to, rather than because they have to, due to some environmental or economic calamity. It’s impossible to bike through these cities and not think that that’s the inevitable endgame for the road we’re currently on.