Author: Design Workshop

The Road to Reimagine Benjamin Franklin Parkway: Creating a People-Centric Parkway

By Corey Dodd and Tarana Hafiz

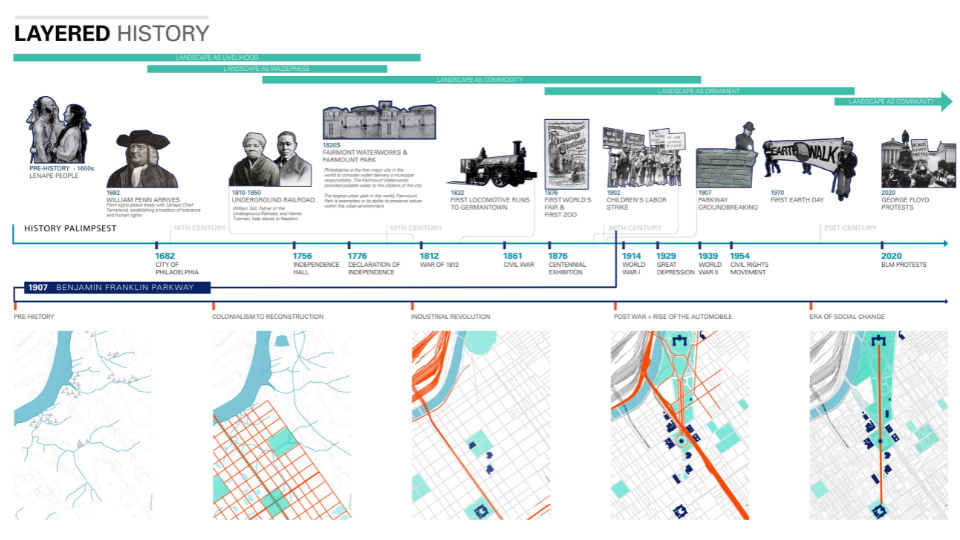

In the fall of 2021, the City of Philadelphia embarked on a project to Reimagine Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Along with other iconic, historic cities around the world, Philadelphia is following suit with reinvestment in the public realm, featuring a more pedestrian-friendly approach to the historic corridor. Today the Parkway serves as the city’s hub for cultural institutions, a venue for large- and small-scale events, a destination for exercise, play, and social activities, and as a promenade for peaceful civic demonstration. A goal of the project includes honoring the historic design intent of the Parkway which stems from the City Beautiful Movement that claimed design could not be separated from social issues and should help facilitate civic pride and engagement. Also crucial to the Parkway’s future legacy is celebrating Philadelphia’s cultural richness and diversity, and embodying the hopes and dreams of its citizens by weaving education, civic assembly and recreation in an inviting, safe space.

The reimagined Parkway will be repositioned from one that is a ceremonial thoroughfare made for the automobile, to one that reflects the hearts and voices of all Philadelphians. The community holds an integral role in the process to build a more “people-centric” space. This is an opportunity to address tough questions, and the Parkway, if designed right, has the potential to be a space for escape and expression when faced with issues of our current socioeconomic climate – an ongoing pandemic, racial and civic injustices, and challenges such as homelessness and violence. This project represents a new light and an important time where, together, we are co-creating what a free and fair public space means for Philadelphia and how it can be optimized for all people.

Image: Design Workshop

As with any major city, Philadelphia has continued to evolve since the inception of this incredible example of civic art in the Beaux-Arts style and serves a far more diverse and denser population than when it existed in 1917. Recent urbanization trends challenge the design of this grand civic space. The expansive linear streets once adept for guiding residents and visitors between the museums, artworks, and railroad stations that lined the Parkway are now dominated by commuter motorists. These multiple-lane freeways fragment the public realm by dissolving spatial definition and creating challenges for accessing the boulevard and its institutions as a pedestrian. In our conversations with the people of Philadelphia, one thing is clear – the foundation of the vision is to build a destination for people, not vehicles. By making the Parkway a place to come into, not through, we can reestablish connecting the public to the city’s immense playground.

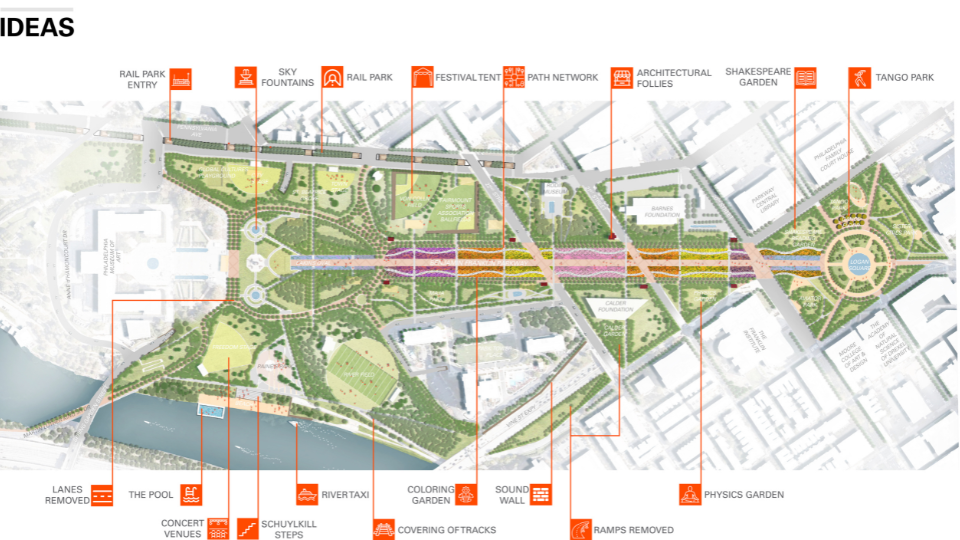

Currently, the Parkway is characterized by its edges; the edges are where it is safe to stroll or roll your way between institutions on shaded walkways. In the effort to make the parkway a holistically welcoming place and a green transect that allows a pedestrian to experience moments from Love Park to the Oval without physical or behavioral impediments, there is a need to turn the park inside out, allowing the character to expand toward the edge. Continued opportunities for public art, creation of nodes and the implementation of pocket parks or plazas will serve as connective tissues between institutions and neighborhoods. The provision of an informational center to keep users up to date on the happenings of the Parkway and direct passersby have all been reoccurring themes for amenities defined by stakeholders. The result could strengthen the central arms of the boulevard and stretch to the park’s edges. The Penn Avenue Initiative in Washington D.C., Passeig De Sant Joan Boulevard in Barcelona, and Times Square in New York are examples of public spaces that have reintroduced the notion of energizing streets by right-sizing them for people. This project provides a chance to not only learn from such precedents but truly embody the idea of a “democratic landscape” through design elements such as activity zones, symbolic art, defacto stages, widened sidewalks, welcoming gardens, and assembly spaces; essentially programs that cater to a variety of people and their backgrounds.

Image: Design Workshop

Paths and plantings are the backbones of the park, but people are its lifeblood. The people who regularly visit this public green space come for varying reasons and their presence is a welcoming attraction to others. While special events are an important aspect of the park, other programs will be developed to provide a balanced and continuous attraction to visitors, strengthening the park’s mission. Opportunities for future partnerships exist with neighborhood schools for youth engagement in public art exhibitions and outdoor learning labs. For example, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society could lead rotating cohorts to engage community members in learning and providing support to maintain Parkway plantings or a community garden space.

Reimagining Benjamin Franklin Parkway provides the prospect to face topics of healing, progress, and innovation. This can only be achieved by going directly to the community and learning from the untold stories and perspectives that will break up the monotony of this largely whitewashed history and make the historically Eurocentric space a place for all voices from diverse backgrounds to be represented. This is not just about a physical place, but a space in time – to catalyze change and have difficult, yet productive conversations around social engagement and community mobilization that speaks to a diversity of patrons. As we move through the design process, the hope is to reach the most marginalized communities of the city, constituents who rarely have a seat at the table during such a planning endeavor and co-create ideas with everyone. Creative engagement methods such as “meetings-in-a-box,” mapping techniques using Safegraph data that helps us better understand neighborhoods under-reached by the Parkway’s current programming, or social media campaigns that provide a platform for discussion and debate around a people-centric Parkway. These are all ways to build a plan that is reflective of the dreams and aspirations of Philadelphians- youth and seniors, BIPOC and white, abled and those living with a disability, advantaged and the disenfranchised.

Image: Design Workshop

Engaging citizens who currently use the Parkway in addition to those who do not but wish to use the space in the planning process is the only way to ensure the long-term sustainability of the park as an inviting, educational and economically viable place. In doing so, offerings that truly meet the desires and needs of residents and visitors who contribute to the vitality of the city will be incorporated into the reimagined design- from safe bike routes to the Schuylkill River, to pop-up kiosks for food and beverage, and multipurpose community hubs for youth activities. This iteration of the design process that relies on public inclusion is reflective of both the evolution of Philadelphia’s demographics since the park’s inception and the evolution of the process of designing public spaces. We are beyond the times when a select few determined when, how, and where changes to the spaces we all wish to enjoy and utilize are made.

This project will impact similar public realm projects with historical significance across the nation by demonstrating that success can be found in maintaining the essence of original design intent while addressing modern needs for accessibility and play. True value of a public space is found when all citizens can identify their likeness in a network of civic spaces – whether that be visually through art, through accommodations for information sharing, or in something as simple as a planting that reminds them of a family garden. These multi-faceted roles of grand pedestrian parkways are vital to the health of cities like Philadelphia because they cultivate an engaged citizenry. The ability of the Parkway to spark emotions and create memories has and will continue to be at the heart of Philadelphia’s beloved park.

—

Corey Dodd is a landscape designer based in the Raleigh studio of Design Workshop. His work centers on cultivating contextually sensitive environments that contribute to the overall well-being of communities by empowering people as placekeepers and placemakers in identifying the inherently special qualities of their public spaces through historical and cultural literacy.

Corey Dodd is a landscape designer based in the Raleigh studio of Design Workshop. His work centers on cultivating contextually sensitive environments that contribute to the overall well-being of communities by empowering people as placekeepers and placemakers in identifying the inherently special qualities of their public spaces through historical and cultural literacy.

Tarana Hafiz is a New York City native and Houston-based urban designer/planner with Design Workshop. She specializes in developing equitable communities, addressing issues faced within public spaces, and integrating outreach to garner support for impactful design.

Recreation as Part of Complete Streets Definition

The COVID-19 public health and economic crisis has allowed and, in some instance, forced cities to experiment with the use of streets for temporary accommodation of recreation, events, dining, protest, school, and as spaces for the public to enjoy time outdoors. But over the course of history, many U.S. cities have designed and used some streets for park and civic gathering purposes and not just moving people. We suggest we can learn from both history and these recent experiments in street uses so that these temporary experiments can become more permanent and high-quality long-term solutions.

In 2014, landscape architects and planners from Design Workshop authored an article in Planning Magazine titled “Recreation in the Right-of-Way”, which made a case for including recreation as a metric for Complete Streets design. In this research we found reasons street functions have been limited historically, identified common barriers to change, and pointed to lessons from successful expansion of street purposes. This is an ideal moment to capitalize on current interest and momentum to put these lessons into action by advocating for long-term solutions.

In recent years, planners and designers have thoroughly dissected the “why” behind roadway design. Some streets reflect travel demand model requirements, some are outcomes of policy and institutional management structures, while other conditions reflect funding or grant procedures and requirements. Regardless, street design is always an exercise in establishing priorities as matters of public policy. We feel that defining and expanding this public policy component can be key to significantly enhanced use of our cities’ streets.

Cities across the country, along with their state transportation departments, are adopting complete streets policies, and using various transportation-related performance measures to rank results. Design Workshop is involved in many of these and related transportation planning and design projects that consider land use, economic development, green infrastructure, air quality improvements, placemaking and branding along with the needs to move people. This has represented a significant shift in approach and priorities; however, we have yet to fully understand the other changes in behaviors, priorities, funding and policy that have occurred and continue to develop during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Brookings Institution notes that up to half of American workers are currently working from home, which is more than double the fraction who worked from home within the past two years. Many companies interviewed as part of this study have committed to a future of remote work for at least 20% of their staff, which could mean a significant reduction in commuting traffic on streets in the long term. Travel patterns to schools are also in flux. As dedicated funding for parks and open space continues to dwindle during the COVID-19 crisis, the National Recreation and Parks and Recreation Association (NRPA) has noted that “now is the time for park agencies to align investments with other local programs and policies, to tap new funding in creative ways, while benefiting the community.” As our priorities continue to shift, we should consider recreation-broadly defined- as part of the Complete Streets definition. Recreation should become a critical factor within the prioritization process that embodies street design.

Over the past six months, shelter-in-place policies and closure of gyms, recreation centers, and some neighborhood parks and playgrounds to slow the spread of virus have caused people in cities and small towns to turn to streets for outdoor recreation in many forms, from simply walking to biking and other non-motorized activities. The Trust for Public Land estimates more than 100 million people across the country do not have a park within a 10-minute walk of home. In places constrained in meeting park provision goals, existing street rights-of-way should be evaluated as potential spaces to meet these critical standards. Streets can still serve to move people while also serving as linear parks, pocket parks, desirable places for strolling, playing table games, interacting with art, gardening, seating, exercise and play. By avoiding the purchase of new park land and removing it from the tax rolls, cities can further leverage the public land they already own and enhance quality of life in the process of saving money.

In the U.S., more than $180 billion dollars (or 6% of direct general spending) is invested into our highways and roads annually, according to the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. We feel this significant investment should be directed to solving more than vehicle mobility needs, and many ostensibly “temporary” COVID-induced adaptations to streets can be made permanent enhancements to the public realm. In addition, as we move forward from the pandemic, our parks and open space planning methodologies need to assess opportunities for non-traditional recreational spaces to improve equitable access to all forms of recreation, including the opportunities to utilize street right-of-ways.

In studying successes and shortfalls, the following are some of the lessons we have found to be universal for U.S. cities.

Lesson 1: Establish or Realign Public Policies. Cities must establish the goals of broader usage of streets as matters of public policy. Once the policies are established, the procedures to implement and maintain those policies can ensue.

Lesson 2: Coordinated Planning. City and regional planning typically includes numerous system-wide plans for bicycle and pedestrian facilities, comprehensive plans, transportation master plans, complete streets, downtown visions, sustainability, and parks, recreation and trails–all addressing goals for community health and infrastructure planning. While these plans are intended to ultimately reference each other, they rarely are coordinated to examine complex demands on a roadway. When working at the system level, these planning efforts can and should be undertaken simultaneously to coordinate identification of multiple desired purposes of streets.

As an example, Adams County in Colorado is currently undertaking three system-wide plans at once, including a Comprehensive Plan, a Transportation and Mobility Plan, and a Parks, Open Space, and Trails Plan. This integrated effort has provided the opportunity for Design Workshop to use park accessibility gap assessments to direct land use planning and transportation infrastructure improvement for such things as a civic plaza and outdoor exercise equipment within a transit hub.

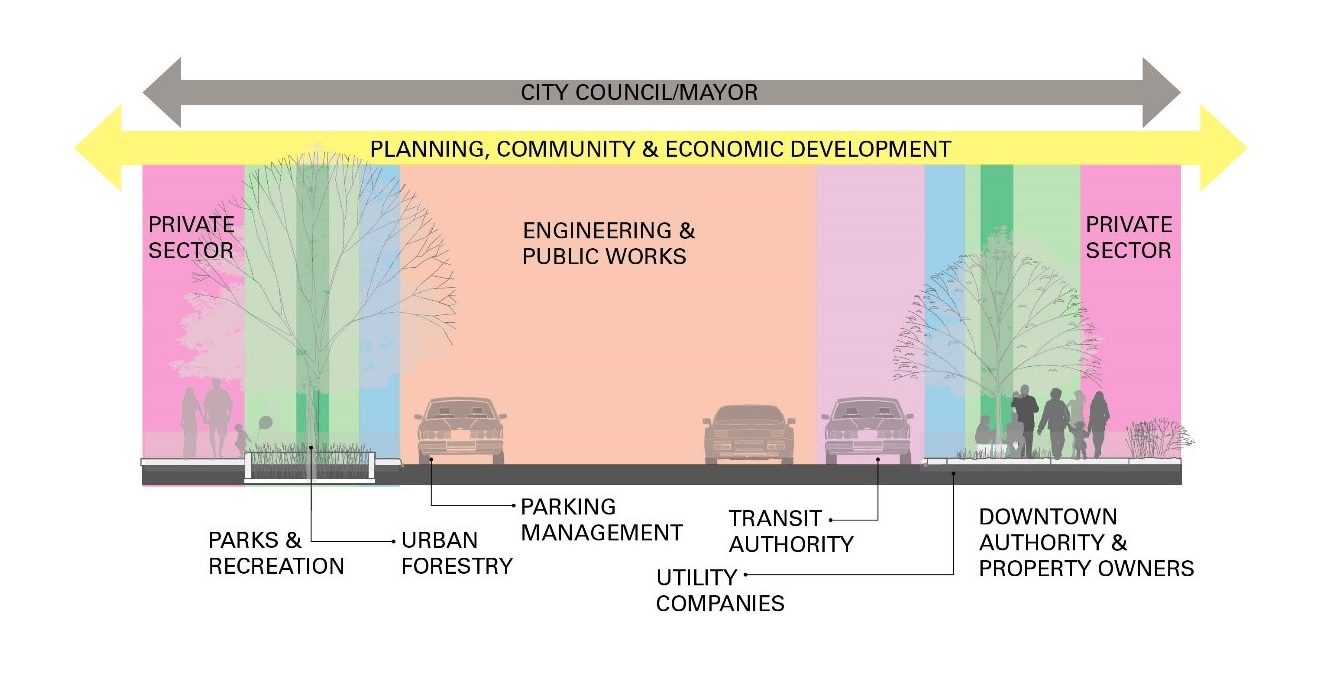

Unifying objectives of multiple plans and departments/entities is key to implementing non-standard street designs. Image: Design Workshop

Lesson 3: Unify siloed departments’ efforts on street design matters. Making the invisible lines of street management responsibilities visible and coordinating early and often is necessary for making less-traditional street use feasible. Every community and street have a different overlay of responsible entities that may include public utilities, stormwater management, urban forestry, Business Improvement District, downtown partnerships/authorities, special events, parks, fire/emergency response, transit entities, city engineering, public works, community development, parking management, street maintenance and private sector interests. Some may influence design standards and others may focus on maintenance or programming needs. When non-standard approaches, different objectives or conflicts are encountered, it is often best addressed in multi-department collective problem-solving discussions.

Lesson 4: Challenge and test the relevance of all parts of existing streets. For examples, ask questions like: Is that right turn lane needed, or could it become part of a small new neighborhood plaza to host the annual tree lighting? Does this street need a center lane, or could it become an open space for trees and stormwater infiltration?

Funding sources and their requirements may be clues in answering these questions. Some of these requirements may lead to providing a “solution” that only checks a funding box and isn’t necessarily reflective of what the community desires. Federal transportation grants do not prioritize all kinds of “recreation” – they mostly require alternative modes of transportation, bike lanes, etc. An alternative funding source, for example, Housing Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) can be used to address a range of public infrastructure and facility projects that benefit low-income communities. Know the policy framework. Are you questioning a street within a city jurisdiction or a state DOT? The policies, priorities and regulations within each may differ greatly.

Lesson 5: Advocate. While performance measures are now a standard approach in corridor planning and street design, few address the recreational and parkland qualities of the street environment. Urban designers should promote this approach to organizations such as SITES, NACTO, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, and WalkScore–and advocate for these objectives within funding proposals and grant applications.

Triangle Plaza in Denver serves as an urban stage for people-watching and interaction, located on an abandoned street right-of-way linking Union Station and the Pepsi Center. Anchoring the plaza’s southern edge is the ‘swing forest,’ which consists of custom-designed swings affixed to curved railroad rails.

Image Copyright: Brandon Huttenlocher photographer / Design Workshop, Inc.

Lesson 6: Look for models that have stood the test of time. While urban designers and engineers may differ on design approach or standards (lane widths, turning radii, turning movements, access drives, etc.), real-world examples are a critical communication tool for reaching consensus. Streets around the world have served as portals for recreation throughout history. Strolling, people watching, chess games, reading – these are all forms of recreation. The original design intent of many of the world’s famous boulevards and promenades was to inject a recreational function by serving as linear parks within newly developed areas of cities, sometimes dedicating 70% of the right-of-way to “recreation” as we have defined it here.

To further understand these spaces and their intent, designers can easily reference “The Boulevard Book,” and “Great Streets,” both by Allan Jacobs. Jacobs notes in “The Boulevard Book,” that streets respond to many issues that are central to urban life, including livability, mobility, safety, interest, economic opportunity, mass transit and open space. While Jacobs’ grand examples like Boulevard de Rochechouart in Paris and Las Ramblas in Barcelona offer an inspirational starting point, there is a growing catalog of examples of all scales of intervention – some simply reclaiming turn lanes to create a corner plaza space or prioritizing recreational spaces over parking in targeted areas. Other examples that may literally be built upon are often found in the local historical record. Many cities that existed before the motor age were creative in their use of street space and older photos, paintings and post cards can often serve as good references.

The Colorado Springs Downtown Parks Master Plan designed Alamo Park to overtake one row of on-street parking and a travel lane to create a pedestrian promenade and festival street, providing infrastructure for market and event booths, outdoor dining, and food truck stalls. Source: Design Workshop

We believe it is time to reclaim the street for a more comprehensively-defined set of purposes — to accommodate the diverse needs of a community including recreation and parkland. As we navigate the COVID-19 pandemic and our exercise in prioritization shifts, we should reference these precedents to make the case for measuring the area devoted to street recreation and park space within our street rights-of-way. Jacobs notes in “The Boulevard Book” that public streets should seek to serve multiple purposes, acknowledging that “not all streets can or should do so, but some can and must.” Streets have the capacity to integrate rather than divide neighborhoods and communities, and within some, the capacity exists to further city-wide or regional targets for open space and recreation. Inequities in park quality and access have always existed in communities across the U.S., but the current pandemic has further exacerbated this challenge. Streets can provide many opportunities for public reinvestment, and by providing the necessary community space needed for mental health and physical safety at relatively low costs, can thereby create a rich set of sustainable public benefits for all.

—

Authors:

Anna Laybourn, AICP is a Principal at Design Workshop, an international design studio providing landscape architecture, planning, and strategic services. Anna’s diverse experiences in community, regional, and land planning are united by a focus on people and planet. She forges the natural and social sciences in her work on parks and open space master plans, transportation infrastructure design, and development proposals.

Sara Egan, PLA, AICP, LEED AP® BD+C is an Associate at Design Workshop’s Chicago studio. Sara’s experience at the implementation scale informs the execution of her work at the strategic and regional scale, focusing largely on transportation corridors and public realm design.

Lead Image: As density increases in downtown Wheaton, Illinois the Downtown Plan identified strategic creation of new public spaces including the transformation of a section of angled parking into a permanent public plaza for outdoor dining and events. Image Copyright: Brandon Huttenlocher photographer / Design Workshop, Inc.

Updating Denver’s Urban Drainage Systems to Handle the Impacts of Development, Population Growth and Climate Change

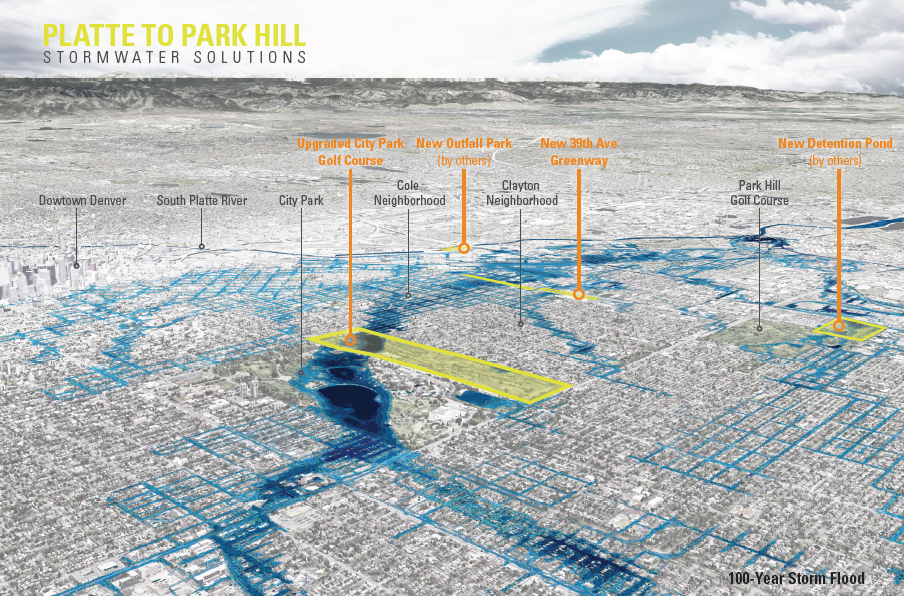

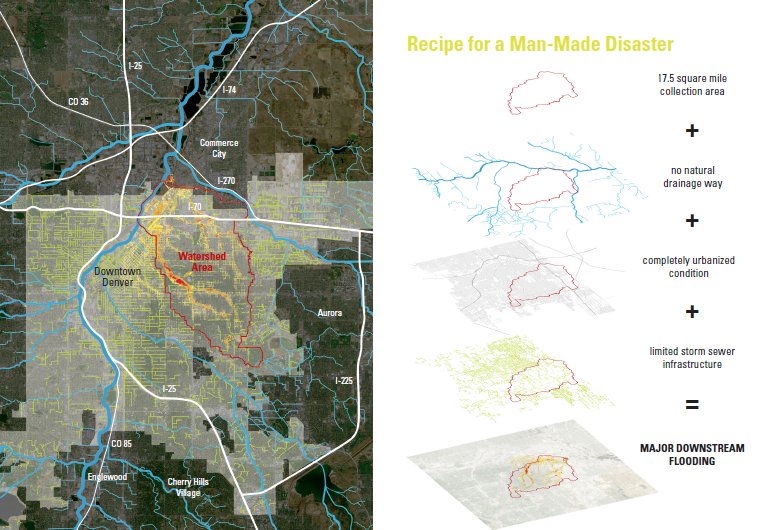

Since its founding in 1858, Denver, Colo. has been a city marked by periods of rapid growth and expansion. During once such period in the late 1800s, over three square miles of land to the northeast of downtown was completely urbanized in less than a decade. Unfortunately, in their haste developers failed to recognize the importance of a vital drainageway that collected stormwater from the Montclair and Park Hill drainage basins, a watershed covering over 17 square miles. As the area transitioned from natural rolling plains to a grid of paved streets and rooftops, an insufficient piped stormwater system soon led to floodwaters lapping at the doors of the residents who had settled in the working-class neighborhoods of Cole and Clayton. Reporting on this flooding dates back to the early 1900s, yet in the century since the city only made minimal attempts to mitigate its impacts. In 2015, the City and County of Denver committed to stormwater infrastructure investments benefitting the Cole and Clayton neighborhoods and soon after created the Platte to Park Hill project.

Image: Design Workshop

From an early stage in the planning process, it became apparent that this project presented the opportunity to not only mitigate flooding, but to also improve the quality of life and health of underserved residents. Both the Cole and Clayton neighborhoods have suffered from a lack of parks and open space. The presence of large industrial properties had disconnected the street grid, and unclean urban runoff contributes to decreasing water quality as the water flows toward its ultimate destination in the South Platte River. As a result, the provision of new recreational and mobility facilities, the reconnection of the urban grid and the incorporation of water quality best practices were adopted as critical success factors for the drainage system project.

Image: Design Workshop

Large-scale problems require large-scale thinking

In approaching this challenge, the team understood that all options needed to be on the table and restoring the hydrological functionality of one of the city’s largest watersheds wasn’t going to be easy or without controversy. With little city-owned or vacant land in the at-risk neighborhoods, the acquisition and demolition of private property needed to be considered. The city-owned City Park Golf Course could be used as a mediation strategy, but not without significant impact to this important urban open space. Neither of these options would fix the entire flooding problem, and compromise was needed to balance neighborhood concerns.

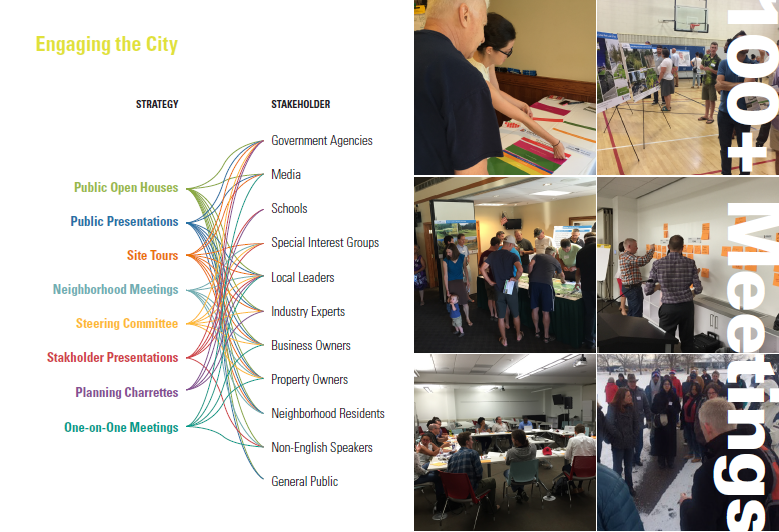

With this understanding, the project team adopted a robust, multi-faceted engagement strategy that extended beyond the standard public meeting format to reach directly into the homes and businesses of community members. Over 100 meetings in various form, setting and scale were employed to ensure that the hopes and concerns of the city’s residents were heard. These meetings took the form of listening sessions, bus tours, open houses, neighborhood meetings, steering committees, native language sessions, and one-on-one sit downs. Not everyone was happy about the project, and not all desires were able to be met, but those who wanted to be heard were heard. This resulted in a project the met the needs and hopes of the majority of community members.

Image: Design Workshop

Overlaying the community engagement with the project’s complicated technical needs resulted in the development of an intervention strategy comprised of four individual parks and open space projects that would work in concert to capture and detain stormwater flows within the watershed and ultimately convey it to the South Platte River. While all four projects have their challenges, the two most disruptive projects proved to be a new 14-acre greenway and the redesign of the city-owned City Park Golf Course which includes:

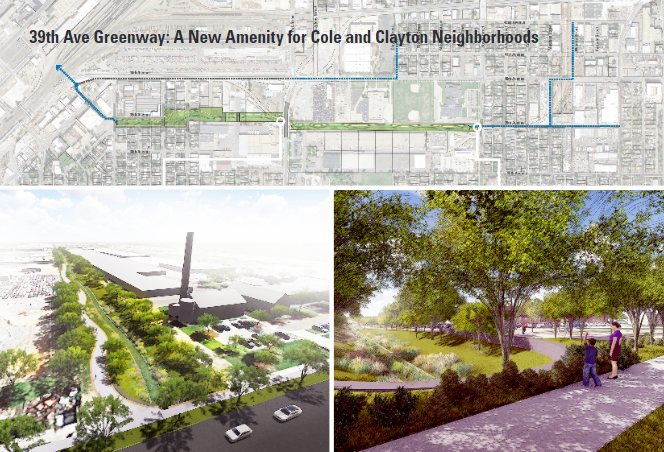

- The 39th Avenue Greenway

The primary challenge in designing the 39th Avenue Greenway involved capturing the community’s desires for both an engineered flooding solution and a high aesthetic character and quality. One of the primary issues in the basin is the quality of stormwater run-off in piped underground infrastructure. To mitigate this, the new 14-block long greenway allows stormwater to move along an open, landscaped channel providing both increased capacity and water quality performance. In addition to being a technically functional solution to the flooding problem, the greenway also provides new open space and recreation opportunities for neighborhoods in need. The greenway also limited the need to condemn residential properties in the neighborhood, instead utilizing an existing disconnected city right-of-way as well as vacant and underused industrial land.

Image: Design Workshop

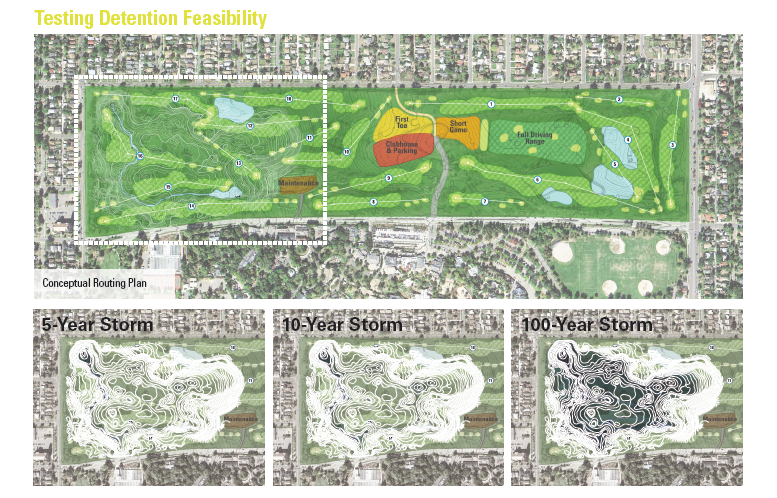

- City Park Golf Course

City Park Golf Course opened in 1913. In the intervening years, multiple changes were made to the course leaving only a historic grouping of trees and the spectacular framing of views of downtown and the Front Range as elements of the existing design – both of which have been included as elements on the course’s listing in the historic registry. Regardless of its historic authenticity, the golf course is beloved by neighborhood residents.

Located above the flood-prone neighborhoods, the golf course is also a 136-acre city-owned open space that is well-situated to mitigate the flooding impacts downstream. Doing so required a redesign of the course to re-grade portions of the golf course to hold and detain flood waters and slow flows through downstream neighborhoods. Working with the city forester, the project team went to great lengths to identify priority trees for preservation as well as significant stands to be saved. As a result, new routing and grading options were developed to maximize tree preservation. Concerns over the impacts to views from surrounding neighborhoods also drove the team to not only identify and catalogue priority views, but to also develop full scale 3D models and visualization graphics for each of the grading scenarios in order to demonstrate how views would or would not be impacted.

Image: Design Workshop

Project Results

The result of these efforts is a project that not only provides additional flood protection to over 5,000 residences, but creates over 17 acres of new parkland in underserved communities, protects 96% of at-risk residences from demolition, reconnects the urban grid, and breathes new life into a beloved municipal golf course while preserving 99% of the priority trees and 100% of prioritized views. Since completing the planning work, both projects have undergone final design and are currently under construction with completion slated for 2020.

—

Article By: Chris Geddes and Marcus Pulsipher

Chris Geddes joined Design Workshop in October 2014. With nearly 20 years’ experience in planning and urban design projects both in Colorado and across the country, Chris brings a perspective to his work that focuses on enhancing the quality and experience of the public realm through thoughtful engagement with those that use it every day. Since coming to Design Workshop, Chris has managed high-profile planning and design projects including the Central-70 Cover Design, Central-70 Aesthetic Standards, the Downtown Denver Parks and Public Spaces Master Plan, and the Colorado State University Medical Center. Chris has a Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder and a Masters of Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Colorado Denver, and is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.land8 banner design workshop

Chris Geddes joined Design Workshop in October 2014. With nearly 20 years’ experience in planning and urban design projects both in Colorado and across the country, Chris brings a perspective to his work that focuses on enhancing the quality and experience of the public realm through thoughtful engagement with those that use it every day. Since coming to Design Workshop, Chris has managed high-profile planning and design projects including the Central-70 Cover Design, Central-70 Aesthetic Standards, the Downtown Denver Parks and Public Spaces Master Plan, and the Colorado State University Medical Center. Chris has a Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder and a Masters of Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Colorado Denver, and is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.land8 banner design workshop

Marcus Pulsipher is a landscape architect, a certified planner and a passionate advocate for environmentally and socially responsible spatial design. Marcus got his start studying landscape architecture at Utah State University and later received a Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design degree from Harvard University, where he was awarded the Outstanding Housing Research and Design Prize. Professionally, Marcus has extensive experience working on and managing complex projects, interpreting and incorporating the needs of various stakeholders into meaningful solutions. He has worked on a variety of projects scales and types, from city-wide planning initiatives to reduce flooding in Denver, to greenway and park master planning in post-Katrina New Orleans. Marcus’s work is driven by a sincere desire to create places and spaces that have a meaningful, positive effect on the lives of the people who live, work and play within them; setting the stage for long term, sustainable community health and well-being.

Marcus Pulsipher is a landscape architect, a certified planner and a passionate advocate for environmentally and socially responsible spatial design. Marcus got his start studying landscape architecture at Utah State University and later received a Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design degree from Harvard University, where he was awarded the Outstanding Housing Research and Design Prize. Professionally, Marcus has extensive experience working on and managing complex projects, interpreting and incorporating the needs of various stakeholders into meaningful solutions. He has worked on a variety of projects scales and types, from city-wide planning initiatives to reduce flooding in Denver, to greenway and park master planning in post-Katrina New Orleans. Marcus’s work is driven by a sincere desire to create places and spaces that have a meaningful, positive effect on the lives of the people who live, work and play within them; setting the stage for long term, sustainable community health and well-being.