Author: Jessica Wolff

Young Leaders at Sasaki Tackle Sea Level Rise in Interactive “Sea Change: Boston” Exhibit

It’s no secret that climate change is a hot topic right now. Due to recent megastorm events, climate change has become a central focus in many professional circles. Within the design realm, Hurricane Sandy’s destruction in 2012 spawned a focus on exhibits in New York City that predicted devastating repercussions if preemptive infrastructural measures were not considered, such as the Rising Currents at the MoMa in 2010. While the exhibits in New York helped spur more discourse about climate change in a design framework, equally vulnerable cities were left out of the discussion.

Enter four budding professionals from the Boston area-based design and planning firm Sasaki Associates. This small group of spirited, driven designers and planners developed a personal research passion into a well-publicized public exhibit. Over the course of the past year, Nina Chase, Ruth Siegel, Chris Merritt and Carey Walker have combined their shared interests concerning sea level rise to produce an exhibit at District Hall in the Seaport District of Boston. Prior to the installation of this exhibit, the group used their sea level rise research to lead the annual internship program at Sasaki, spearhead an important planning document for the city City of Boston, teach students at the Boston Architectural College, garner work for their firm’s urban design and planning studio, and host of series of lectures and discussions about this important topic. The following interview details how these motivated design professionals began a year-long process with a passionate idea in mind which resulted in a lot of far-reaching results…with more to come!

1. First, congratulations on designing, planning and showcasing a fantastic exhibit! Can you please explain how the exhibit work first began, and how it developed into such an elaborate and involved endeavor?

NC: The topic of sea level rise was of personal interest to all of us. After Hurricane Sandy hit, we realized there was a lot of discussion about climate change in the design community of New York, but not as much going on in Boston. But then in February 2013, TBHA (The Boston Harbor Association) put out their Preparing for the Rising Tides report, which was the first time that people could see where flooding was projected to occur in Boston and it sparked a whole series of mini conferences about the subject. We thought that it would be a good time to insert ourselves as leaders in that conversation.

RS: There were a lot of symposia and lectures that were mostly people from New York talking about Hurricane Sandy. We were attending a lot of these events because we were interested in the topic, then we started talking about how there was no local design firm leading the discussion about what’s happening in Boston with respect to designing for sea level rise. So we saw that as an opportunity.

NC: Next we started talking about the research opportunities about sea level rise at Sasaki and we pitched it as an in-house research project. Urban Fabric had happened a few years ago and that was something we wanted to emulate – the model of research in professional practice and bridging the gap between what we were doing in school and how we are practicing. Urban Fabric was really an inspiration – we used that model and pitched the idea of sea level rise as the topic and Boston specifically as the location.

RS: That was something that was exciting me about Sasaki as a potential employee. We were just starting as employees and wanted to do something important and meaningful, not just for ourselves, but for the firm. We are very lucky to have such supportive leadership who saw potential in this idea and encouraged us to pursue it.

2. On a side note, how has this research work parlayed into actual work for the firm?

NC: The crazy thing is that it’s been in tandem – at the same time that we have been doing the research for Sea Change, opportunities have been coming up for the firm through the Sea Change work like marketing the initial research we had done. We packaged it roughly and used the graphics, methodology and framework for what we submitted for Rebuild By Design competition this past August. We are also partnering with TBHA on their next report, which is focused on design strategies as they relate to sea level rise.

3. How did your successfully pitched research ideas about sea level rise transpire into the main topic for Sasaki’s internship program last summer?

CM: Typically the internship charette works with an existing or prospective client and a few in-house people lead a local studio-like project. There wasn’t an idea fully formed yet for that year’s program and we had started this research so it was perfect timing.

NC: Our research already had us thinking at a larger scale of Boston, so we thought the interns could zoom in even further to South Boston (#SummerofSLR), and the Boston Architectural College studio (#SemesterofSLR) in the fall could focus on East Boston. It was nice because our core team focused on the larger scale research and the interns and students focused on site-specific ideas. Coming from students, it was easier to be provocative, not being confined by clients’ expectations and financial limits. RS: We have hovered at a slightly abstract level of design because it’s a highly controversial topic. We as a firm, didn’t want to say “this is what we should do here” because there are a lot of ways you can design to address the problem.

CM: We also wanted to address the larger regional complex issue of sea level rise without diving into one site saying “this is what we have to do here”. We wanted to give a holistic approach or an idea about a strategy to approach sea level rise for the Boston metropolitan region.

.(Related Story: 5 Resiliency Lessons from NYC Stormwater Projects)

4. In order to reach a broad audience, and not just designers and planners, what were some of the graphic techniques that you found most helpful to use?

NC: We had a really amazing graphics team at Sasaki that worked with us to help us focus the storytelling and the brand to make it so that we could introduce huge concepts but bring them down to a level that could be easily understood. There was also a lot of writing involved, so we had to distill it down.

RS: There were word counts for every board. We wanted to make sure people would actually read it and not get lost in the text, so we had to edit, edit, edit.

CW: This meant that the graphics really had to stand on their own.

NC: One of the cool things about the branding strategy was that the title and key points were highlighted like a science textbook.

CM: It was huge to have the graphics team so that we would have someone on hand to think how someone experiences an exhibit and know about placement of images and takeaways.

NC: The location of the exhibit was very important. District Hall in the Seaport District had never had hosted an exhibit before and the 4 of us had never done anything like this, so there was quite a learning curve. But since the venue attracts such a diverse audience beyond the design community, we saw it as a perfect venue for getting this work seen by the public. RS: We had to work with the graphics team because the space is not set up as a “proper” exhibit venue. District Hall is set up to be a flexible space, so that had to be built into our exhibit. It turned out to be a great design challenge for us which led to our free-standing “hubs” – we feel these vertical elements really populate the space and create a major presence for the exhibit.

CM: I think just being accessible to the public is the biggest thing. It could have been set up in a beautiful exhibit hall, but it wouldn’t reach as many people.

RS: We also have gotten walk-ins from people visiting the nearby cafe. People have been posting images of the exhibit on twitter and Instagram saying thingslike, “I came in for a cup of coffee and learned all about sea level rise! This is amazing!”

RS: District Hall is also in the flood plain, located in the Innovation District of Boston, which has a lot of development projects currently underway. The 2100 projection of sea level rise hits the second stair outside of the building This was a major opportunity for us to visualize the problem of sea level rise – we literally could say “high tide could be here in 2100 if nothing is done.” Our stair riser flood level graphic was reportedly one of the most powerful components of the exhibit. So simple, yet so effective.

5. What was the most helpful thing that you learned from partnering with other organizations in planning Sea Change events? How do you think these partnerships will benefit the project’s main initiatives? And furthermore, what advice do you have for landscape architects and planners who are interested in reaching a broad public audience with their design initiatives?

NC: The audience that we were able to reach by partnering with THBA and the city were totally different than who we would have reached just through Sasaki or the Boston Architectural College. For us, that was one of the fantastic outcomes – that we were able to reach a broader community.

RS: The variety of people able who were able to come to the opening and symposium was also amazing. There were so many people we didn’t recognize at these events – I kept asking people how they found out about the exhibit, and I got a range of answers, but they all seemed to connect back to the city or TBHA.

CW: Which was exactly what we wanted!

NC: The idea that “climate change is bigger than any one organization” was key. Partnering with a government organization and one of the largest non-profits in the city whose entire mission is about the harbor, and they started the sea level rise conversation initially. We brought a lot of people into Sasaki as part of the intern charette and met with people from the city and TBHA. From the beginning we have been plugging in different experts and that has coalesced into the exhibit and lecture series.

One of the ways we partnered with the city was the Greenovate program, which is about climate change preparedness and engaging with the community to get feedback. They have a question page, “What would you do if sea level rise happened in your neighborhood” which we link to in the exhibit. The addresses that people put in for the interactive feature are being collected so that the city can see the areas that people are worried about.

(Related Story: Landscape Architects Chosen as Finalists for Rebuild by Design Competition)

6. It seems like a lot of efforts in the United States is reactive. It’s not until a Hurricane Sandy happens that there is a response.

NC: That was something that came up at the symposium. Do we need a trigger or can we be proactive and invest proactively.

RS: And that was one of the goals of the exhibit, to wake people up. In this country, the “out of sight, out of mind” response tends to be more accepted than being proactive. But there have been three or four near misses in terms of major storms recently which could have caused substantial damages in Boston.

7. What future goals do you have for Sea Change? Will this be exhibited elsewhere? Published?

CW: I think it’s really important that it’s a continued thing. The problem is not solved and we are just starting this conversation. This exhibit is the first step in reaching the external audiences that need to be reached and the next step is actually doing something.

NC: The ultimate goal was to create a regional plan specific to sea level rise and that conversation has started.

CM: And it’s something that we didn’t even bring up as a marketing thing for Sasaki, it’s something that came up through doing the research, that every city needs to be thinking this way.

RS: It would be fantastic if a regional scale plan would come out of this, no matter who does it. In terms of the exhibit, we have been talking with other interested parties who want to take the exhibit “hubs” and put them elsewhere to be displayed. That is an unintended benefit of these free-standing display “hubs”, that they are transportable and not on a wall. We’d like to do a book, whether or not that’s digital or printed, or both. And we’re talking about the potential for the interactive map that was created to go on the road. As of very recently, our interactive map is now available on the internet and can be viewed on tablet devices.

NC: We’ve just had the interactive map reformatted so that there is a version that is displayed on the huge touch screen at District Hall, and also one that can be used on an iPad or computer.

RS: One final thing is that when we started this process we put a colon in the title with the idea of this could be done in other cities. For example, “Sea Change: Miami”.

CM: Even if we don’t take this and repurpose it and package it for another city, it’s something that can speak to the bigger picture and start an important conversation.

**The Sea Change: Boston exhibit will be on display at District Hall in Boston’s Innovation District until June 13.**

You can also see their full presentation on Slideshare here.

See these links for some of the groups related efforts and projects:

Sea Level Rise exhibit

http://www.sasaki.com/project/360/

Rebuild by Design Design Competition

http://www.sasaki.com/project/335/rebuild-by-design/

Interactive Map

http://seachange.sasaki.com/map/

Greenovate Boston

Sea Level Rise: Boston Sasaki Intern Design Charette

http://issuu.com/sasakiassociates/docs/master_book_executive_summary_for_i

Nina Chase as a panelist at the Boston Society of Architects Event, Troubled Waters: A Public Forum

http://www.architects.org/news/video-troubled-waters-public-forum

Twitter Hashtags:

Participating Groups:

The Boston Harbor Association (TBHA)

Composite Landscapes: Photomontage and Landscape Architecture

(A collaborative article by Jessica Wolff and Cortney Kirk)

By breaking the rectangular frame (implying the photograph), the viewer is drawn into the frame. This is at the heart of the Composite Landscapes Show: by drawing the viewer into the image as intimately as possible, the hope is to produce a greater understanding of the fact that the way we draw and represent the landscape is a direct representation of the way we experience it – the things we see, touch, smell and hear are difficult to abstract on paper, but through the development of expressive photomontage techniques, these and other images attempt to express a highly individual yet publicly accessible interpretation of the complex, ever-changing landscape.

– Andrea Hansen, Curator of the Composite Landscapes exhibit at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

This past week was the opening of the first landscape architecture exhibit to date at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. Composite Landscapes: Photomontage and Landscape Architecture features such notable landscape architects as Michael Van Valkenburgh, Gary Hilderbrand, Ken Smith, James Corner, and Claude Cormier, but also showcases artistic work by such David Hockney, Byron Wolfe and Jan Dibbets, as well as Isabella Stewart Gardner herself.

John Stezaker

Mash XLVI

2007, Collage, 9.8”h x 8”w

London, The Approach Gallery

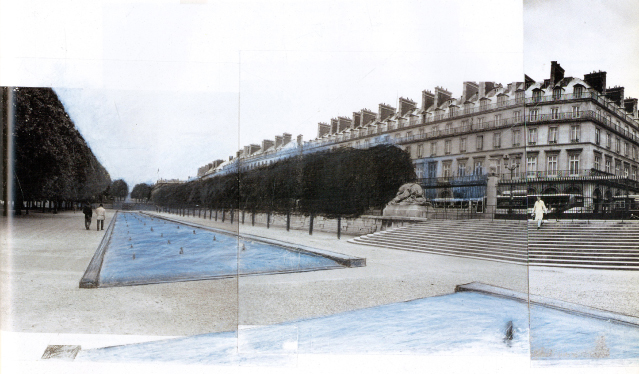

Michael Van Valkenburgh

Experiment al fish farm along the rue de Rivoli, Jardin des Tuileries

Paris, 1990, photo collage, 24”h x 36”w

New York, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates

Coupled with the opening of the exhibit was a lecture and panel discussion led by Charles Waldheim, the Ruettgers Consulting Curator of Landscape at the museum and Andrea Hansen, the exhibit’s Assistant Curator. The panelists included Gary Hilderbrand, Principal of the landscape architecture firm Reed Hilderbrand and Adjunct Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and Robin Kelsey,Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography and Director of Graduate Studies in the History of Art and Architecture Department at Harvard University.The lecture and panel discussion introduced the exhibit through the history of montage, with the eventual introduction of photography and subsequent medium of photomontage.

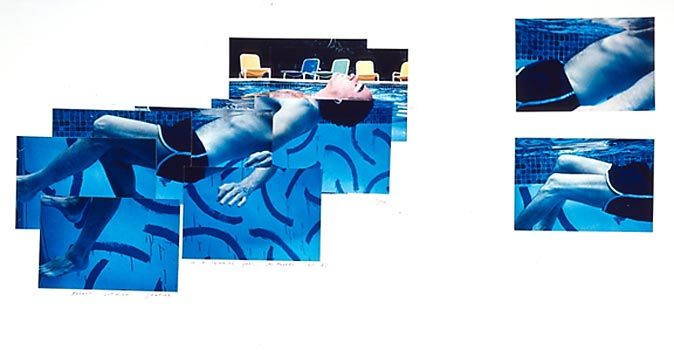

As Assistant Curator of the exhibit, Andrea Hansen began the discussion stating that photomontage is the most universally legible medium in comparison with plan and section and can be utilized to highlight temporality, fantasy, and the synthesis of complex ideas. Hansen defined terms that were created by the artists themselves in the process of experimenting with the art of photomontage, such as James Corner’s use of the “ideogram” which broke the frame of the image in order to draw the viewer into the perspective scenery. This work was influenced by Hockney’s “joiners” technique, which effectively combined large-form polaroid photos, revealing a subject in motion in both time and space. Both pieces are included in the exhibit.

David Hockney

Robert Littman Floating in My Pool

Photographic collage

October 1982

22 1/2”h x 30”w

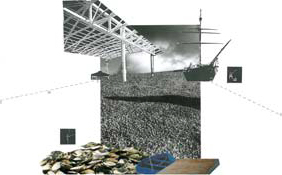

James Corner

Ideogram, Greenport Harborfront, New York

Photomontage

1996

14.25”h x 22.25”w

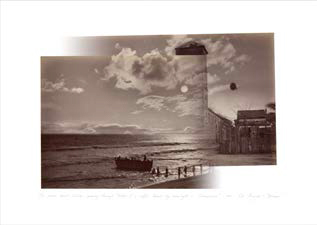

Robin Kelsey framed his discussion by defining photomontage as an artistic process, a tactic of consumption, a mode of persuasion, reconfigured space and time, critical revolutionary practice, and design principle. Kelsey focused mostly around the photographic process, citing Byron Wolfe’s work where he reveals the secrets of well know photographers by creating an image that makes viewers aware of a particular photographic technique. For example Kelsey spoke about ‘The same sunlit clouds,’ a piece in the exhibit where two separate travel images taken by Eadweard Muybridge were overlayed by Wolfe to reveal Muybridge’s technique of using the same photo negative of clouds during the printing process of both photos. Kelsey continued with how certain photographers would use their own discretion to artfully craft an image as opposed to a recording of a moment.

The same sunlit clouds passing through “Return of a coffee

launch by moonlight – Champerico” and “Las Monjas – Panama.”

Individual album pages from The Pacific Coast of Central

America and Mexico; the Isthmus of Panama; Guatemala; and the

Cultivation and Shipment of Coffee, Illustrated by Eadweard

Muybridge, 1876. (Courtesy Stanford University Special

Collections). Medium: Digital inkjet print.

2010

16″h x 22″

It is clear that the work by the exhibited landscape architects is artfully crafted in many ways similar to photographic techniques discussed by Kelsey. One must walk up and closely and examine each piece of work. A closer examination of Adriaan Geuze’s Schowburgplein discloses his material pallet of drafting tape and cut out colored paper, both readily available supplies in a landscape architect’s studio. The work of Yves Brunier in Museumpark, uses more of a contemporary art pallet such as mirrored sticky-backed plastic and paint. Both landscape architects work is distinctive in style and created to represent more than just a photorealistic landscape, it begins to unveil a design process at work.

Yves Brunier

The white orchard on white sand and the reflecting wall,

Museumpark, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Collage, mixed media

1989-1993

Gary Hilderbrand followed with his lecture titled ‘Augmented Realities,’ a talk that highlighted some of his own personal work as well as examples of how photomontage can be emotional, powerfully persuasive and sometimes a deceptive mode of drawing landscape architecture. His works, ‘Almost Nothing’ and ‘Glass House Reflections II’ are a tribute to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Glass House and Philip Johnson’s Farnsworth House. Hilderbrand “juxtaposes photographs of the two masterpieces of modern architecture with photographs of their surrounding landscapes, drawing attention to the way each houses’s glass façade frames the landscape and blurts distinctions between inside and outside, front and back, figure and field”. Hilderbrand spoke very candidly about how drawing landscape in a convincing way is challenging but through the use of photomontage, especially the prolific use of digital photomontage, those with basic hand drawing skills are provided with a powerfully persuasive tool. He concluded his lecture with some ruminations about the forecast of digital photomontage in the field of landscape architecture, postulating that the field might soon be at the cusp of yet another revolution in visual representation.

Gary Hilderbrand

Glass House Reflections II

2012, Handcut collage/montage, offset print, handmade paper, 6”h x 5”w

Private Collection

This is a collaborative writing piece by Jessica Wolff and Cortney Kirk. Composite Landscapes will be at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum through September 2, 2013. It is a delight that this exhibit is available to a non-design audience, allowing the viewer to step into the design world where many drawings are created before, if ever, a landscape is constructed. The exhibit is a valuable record of the landscape profession as it emerges into the digital age – a must see.

Also on display in the museum’s new courtyard is Tiny Taxonomy, an installation of small, hearty plants commonly found in rocky, high altitude environments, created by Rosetta Sarah Elkin.

What do you think? Please leave your thoughts below…

Member Spotlight: Interview with Bradley Cantrell

Bradley Cantrell is the most recent winner of the Rome Prize Fellowship in Landscape Architecture and newly appointed head of the Louisiana State University Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture. His research interests involve the art of ecological design through computing, responsive technologies and data visualization, and has explored these subjects as Director of the Terrain Kinetics (TiKi) Lab. With a promising future ahead of him, Bradley shares with us his goals for these next monumental steps in his career.

Figure 01 . Sediment Deposition Patterning Utilizing Autonomous Sediment Drones

Credits: Fall 2011 Responsive Systems Studio, Bradley Cantrell. Students: Charlie Pruitt, Robert Herkes, Brennan Dedon

First of all, congratulations on winning the Rome Prize! What inspired you to apply for this prestigious fellowship?

The history of the award is obviously a big attraction and having my work recognized within the academy is a great honor. My colleagues and friends, Ursula Emery McClure and Michael McClure, encouraged me to apply and as past fellows they felt I would be a good fit. I believe my work in computation is often a tough fit in historically and culturally rich landscapes, therefore it was an inspiring challenge to push myself to find a set of methodologies that would interface with the infrastructure, culture, and history of Rome.

Figure 02 . Realtime Monitoring of Atchafalaya Basin Ecological Complexity

Credits: Fall 2011 Responsive Systems Studio, Bradley Cantrell. Students: Kim Nguyen, Josh Brooks, Devon Boutte, Martin Moser

How do you see your fellowship research contributing to the profession?

I believe the contribution is similar to my full body of work, it will focus on binding together virtualization and the physical world. Specifically, my work during the fellowship will hone in on the more abstract qualities of place and will imagine how we can curate new relationships between constructed infrastructures and biological interventions using responsive technologies. I am focusing on the water infrastructure of Rome and applying responsive technologies through three lenses, as a didactic tool, as a method of purification, and as a method of access.

Since its inception, digital technology has been a divisive topic in the design professions due to the argument that hand drawing is being lost as a method of intuitive conceptual design thinking. Your work seems to effectively fuse these two mediums. In what way do you think digital technology can supplement or advance conceptual design thinking?

One of our biggest issues is that we have applied digital technologies to our analog methods, we are basically attempting to draw, draft, and illustrate digitally using traditional methods. This builds an inevitable tension between the tools. The idea that we are stuck on this duality (analog vs. digital) is unfortunate, it slows down our advancement and muddies any critical discourse in representation. In reality the argument typically comes down to a defense of whatever tool that individual feels the most comfortable with. Hand or analog drawing is important and at the same time so is digital media and design computation. We are at a moment where hybrid solutions are the way we should work.

I will say that there is no particular advantage when it comes to conceptual design in regards to starting with a pencil, a 3d model, or a GIS analysis. The product from these three methods will be different but in the hands of a strong designer any of these tools (and many more) are valid ways to explore design potential, present work to clients, and resolve design intentions. The key for each individual is to develop methods of representation where they feel comfortable representing design proposals at a multitude of stages.

We are currently seeing computation coming of age in our profession as we are developing methodologies that are specific to digital tools. I see the greatest advances in the areas of simulation, particularly in realtime models of environmental processes or ecological systems.

Figure 03 . Physical Prototype of Actuated Surface Responding to Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in the Atchafalaya Basin

Credits: Fall 2011 Responsive Systems Studio, Bradley Cantrell. Students: Justine Holzman, Luke Venable

What is the benefit of using digital technology in expressing the fluidity and time sensitivity of ecological science?

The benefits are embedded in the modeling of these systems. We currently model a static outcome and based on reasonable knowledge, the evolution of a landscape. As we develop and interact with models of these systems we will insert ourselves not only in the design of the initial proposal but also understand how our changes may affect future scenarios.

What designers or research labs have influenced your work and studies?

I admire the work of many people, it is very difficult to put my finger on a single influence. For me there is a huge range and it may sound strange but within that grouping I would put Lebbeus Woods, the MIT Media Lab, and the Army Corp of Engineers.

Figure 04 . Physical Model of MIMMI Concept

Credits: INVIVIA and Urban drc Project Team: Allen Sayegh, Carl Keopcke, Jack Cochran, Yuichiro Takeuchi, Bradley Cantrell, Artem Melikyan, Ziyi Zhang, and Peter Mabardi

Congratulations to you a second time for becoming the newly appointed chair of the LSU landscape architecture program! What are your goals for leading the landscape architecture program at Louisiana State University? Do you plan on staying highly involved with the TiKi lab?

I am excited to be leading a very interesting and dynamic program here at the Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture. The school is situated within one of the most dynamic, important, and fragile ecosystems in North America, the Mississippi River Delta. My goal is to expand our expertise within this environment to other national and international venues. I will remain active in the lab although we are currently undergoing changes and will be renaming the lab as the focus has evolved over the past 3 years.

What fulfills you most as a professor?

Teaching and my research. These are the reasons I pushed myself into academia and each fulfill different areas of my professional life. My research is completely self-fulfilling, I am typically creating or writing about my interests. It almost feels indulgent at times and I feel very lucky to be in a position where I can explore ideas that are truly my own. Teaching for me is about giving back, it takes this moment of indulgence and allows me to give back to students. To help them shape their own perspective on the world. The most fulfilling thing is when I see my research and teaching having a direct influence on an individual’s career or the trajectory of our profession.

Figure 05 . MIMMI at the Minneapolis Convention Center

Credits: INVIVIA and Urban drc Project Team: Allen Sayegh, Carl Keopcke, Jack Cochran, Yuichiro Takeuchi, Bradley Cantrell, Artem Melikyan, Ziyi Zhang, and Peter Mabardi

Finally, what do you foresee the trajectory being for advancing ecological studies through digital media in the profession of landscape architecture, and how do you think the lessons are best conveyed?

This goes back to my previous statement about simulation and modeling. I believe that we will see much more robust environmental simulations as we move forward. We already see this in animation and modeling software with lighting and materials. Lights and models behave with realistic and reliable characteristics and we are able to work with them in near realtime.

As a crude example, if I think back to when I started using digital tools; software such as AutoCAD and Illustrator did not give us realtime feedback. You would draw a line in Illustrator in outline mode, then click on preview which would then take 2-3 minutes to “render” your illustration just so that you could see the fills, strokes, and gradients. The same was true for AutoCAD when zooming in or out would require a “regen” which would render the linework at the new scale. Currently, this how we work with simulations – we model elements, add simulation components, and then we run the simulation which can take hours or even days.

Things will change rapidly when we are able to model elements and see them interact with an ongoing simulation in realtime – we will see how light effects them, how water interacts, and the effects of the environment over time.

Now, it’s your turn! What questions do you have for Bradley? Please leave your questions and comments below…

Member Spotlight: Interview with April Philips

During this month of April and celebrated “landscape architecture month”, let us introduce you to April Philips, a landscape architect and urban sustainability advisor and the principal and owner of April Philips Design Works in San Rafael, California. She is the author of the recently published Designing Urban Agriculture: A Complete Guide to the Planning, Design, Construction, Maintenance and Management of Edible Landscapes. April’s work spans a wide range of project types, but one of her main focuses is creating successful urban farm systems. This interview highlights April’s efforts in bringing urban edible landscapes, systems thinking, and community outreach to the forefront of the landscape architecture discourse.

You are originally from Louisiana but have spent most of your professional life in California. How has this shaped your design thinking?

I like to think that my design thinking has been shaped by the 3 great cities that I have had both roots to and connections to throughout my life – New Orleans, Boston and San Francisco. All of these cities have fascinating and rich cultural and regional landscapes which are steeped in history, narrative layers, specific local ecologies, diverse communities, and a land-people dynamic with water that is to me a biological pull.

I am also a true believer in “essence” or “atmosphere” which I think is from my southern heritage. The distinct mix of humidity, spicy food, jazz music, and musty decay juxtaposed with the new, and its special flora and fauna say “New Orleans” to me in a way that speaks to how I design and how I think about placemaking. Every place should evoke its own atmosphere to the people who will visit it – it could be just to feel comfortable or it could be more than that. I believe that each site talks to us in its own unique way and there are stories of place that the design needs to tap into and explore to find the one that celebrates its own distinct voice.

In some ways, I see designers like being a chef creating a new gumbo – what local ingredients do I have to draw from? What ones do I add for a new twist? What is the key flavor to highlight for this one? Designers do the same thing, just with different ingredients from the earth, air, fire and water.

Being a native of New Orleans and having experience with infill projects, do you have any suggestions for green infrastructure in post-Katrina New Orleans?

Community-based design and dialogue is important in that there is an inherent resistance to outsiders and new ways of doing things in the south. I think the best way to illuminate green infrastructure’s results is to do urban infill projects and let people see the success that would be derived from them. The Infill projects that tie green infrastructure improvements to benefit the local community and local economy will have the best chance of success.

In New Orleans, people are tied to their homes and their heritage in a land-people dynamic that is important to acknowledge. A large scale infill or infrastructure planning project has an uphill battle if it does not take that into consideration. I think small scale successes and innovations can eventually turn this around. The Viet Village project in New Orleans is an example of a project that could do so much if it could find more support and get the politics out of the way.

Viet Village

The book that you recently published focuses on edible landscapes and creating urban farms. What are some of the community outreach processes that must be realized in order for an urban farm to take shape?

First, a few underlying framework items and policies need to be set in place to facilitate urban agriculture within a community. These include understanding how urban agriculture has the potential to shape the physical framework of a community’s daily life. When scale is allowed to be multi-faceted, a system-wide interdependent approach can be intertwined into the existing framework, and zoning should be allowed to be flexible enough to foster new system connections that were not previously envisioned. Urban agriculture can shape streetscapes, neighborhood gathering and circulation, create cultural landscape identity, and provide multigenerational aspects that were not previously planned for or available to a community. Community outreach can begin with this type of advocacy with local politicians to make sure urban agriculture is part of the city and neighborhood plan.

Another consideration is that social and health and well-being metrics are needed that acknowledge the many aspects of food and agriculture that are central to fostering health and happiness in our lives. Food is central to human biology, sociology, and psychology. Everyone needs food to survive, enjoys food as nourishment and celebration, and are connected to others by food as we celebrate or gather for a meal. Food can become a platform or layer from which we address other important elements of community, ecology, and livability including the physical, social, economic, cultural, and environmental health of the city. Food is the gateway to the stakeholder conversations between city, community and project developer or funder.

As far as community outreach for a specific design project goes, the key is to establish a communications and management framework that facilitates collaborative conversations and in following a more cyclic design process from the start. This is what I call in the book the Urban Ag Design Process Spheres, which seeks to harness a lifecycle approach and the creation of an integrated systems framework that considers how to build regenerative capabilities into the system, strives for achieving resiliency, and endeavors to achieve a sustainable lifecycle approach that adds value to the ecological, economic and social benefits of the community. This is a systems thinking-based process that is dynamic because landscape ecologies and people’s relationships to them are dynamic. The stakeholder and visioning stage is a key first step in the design process. If a community feels ownership and is a partner in the creative process for building a sustainable food system this will provide the seed for success as the project evolves. Determining how the farm will be funded and operated is part of the upfront dialogue with the stakeholders.

In the process spheres, one is actually called the “Outreach Sphere”. It is the lifecycle link to the design and planning process of urban agriculture landscapes. Designing and constructing these landscapes is perhaps the easiest part to do in the process. This sphere consists of funding, marketing, education, stewardship, research, policy and advocacy – thus coming full circle for ensuring the foundation for a sustainable food system before and after a project. It is this ongoing cyclical process that needs to replace our more linear-based process of modus operandi in the world of development.

Please divulge some of your favorite “ecodestinations” and case studies that you describe in your book…

There are over thirty case studies in the book that are discussed in detail. Some of my favorites are the local farm-to-table ones that I got to experience firsthand, such as Bar Agricole, a restaurant in San Francisco, and the Medlock Ames Wine Tasting Room garden in Healdsburg, CA. Both of these engage people with edible landscapes in a multi-sensory fashion. That said, all of the case studies in the book demonstrate a tremendous range of where urban agriculture is headed and how designers are shaping these landscapes, small and large scale, in their communities around the world.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden’s new Edible Garden addition is one at the top of my list to see soon. The combination of using edible plants in a visual appealing way to demonstrate that edibles can be beautiful as well as functional is a stunning and quite imaginative example of how designers can integrate edible plants in all of their projects. Riverpark Farm in Manhattan is an edible landscape that pushes the envelope on both the design and community interface. Who knew that “temporary” could look so cool? And an exciting one for my office will be the completion this fall of our 2001 Market Street project in San Francisco, a high-density mixed-use project with Whole Foods as the anchor where we have designed a community garden and a beneficial habitat garden on the green roofs and integrated edible plants into our streetscape design.

I do hope to visit all of the case study projects in the book that I have not yet had a chance to this year – at least the ones in the U.S. but for sure Villa Augustus in the Netherlands is a hotel destination that I have on my must-see wish list, as is Expo 2015 in Milan which will focus on the theme of “feeding the planet” and looks to be like a very inspirational event.

Bar Agricole

Villa Augustus

Riverpark Farm, NYC

How can landscape architects ensure that they are holding positions in governmental positions that would allow for their initiatives to be realized, or be more involved in the public process?

The majority of humans now live in urban environments. If there was a natural disaster or any kind of event that could shut down a city’s food supply chain, supermarket shelves would be emptied within a few days in most large cities. Thanks to our dependence on the globalized food system most cities and their populace would not be prepared for such emergencies. How would people feed themselves? Would they resort to foraging from the city sidewalks or city parks? How would a city feed itself with the current food system in place which does not foster resiliency? How will a populace that is low in ecoliteracy become more self sufficient? How do we create conditions that allow for each community to feed itself? We are now losing farmland at the rate of more than 1 acre every minute. If farms disappear, food will disappear. What can we do to change this trajectory and focus our direction on a new food system model that will meet all of these challenges?

The need for an ecological food model has never been more needed in our cities than now. There are many bright spots of hope that are shining through and we can all play a part in growing this movement forward. At the grassroots level these new urban agriculture projects, policies, ideas, organizations, and forums have the potential to light a spark and spread out into our urban and peri-urban communities as a growing network of urban agricultural systems and create more impetus for a new food system model. This will not happen overnight and it also requires us to not just buy local food from farmers markets, or design local food and farm projects, or create new urban agriculture policies, but also to cultivate, support and facilitate the lifecycle aspects of this growing movement into a real, sustainable food web – wherever we can.

As designers and planners we need to think of ourselves as change agents and participate at all levels of engagement, not just by designing but by taking a more active role in our local communities but also by advancing systems thinking and establishing a sustainable food system model. My belief is that we all need to become more active engaged citizens of the world. I hope that more landscape architects will play a more public role in the future to further and/or lead these initiatives.

What is your favorite example of a “guerilla garden”?

I recently participated in an “Eat your sidewalk challenge” in San Francisco and wrote about it on our blog. It was a mind blowing visceral experience to feel like I was actually a part of the ecosystem of the city. The day-long event was broken into three parts: Forage, Cook and Discuss. Led by Lain Kerr of Spurse, the group of foragers were tasked with finding ingredients in the surrounding city neighborhood to add to the fresh ingredients for the cook-off challenge later in the day. Spurse calls this the “MacGyver the World” mentality of taking nothing at face value. The experience was definitely enlightening and what at first seemed almost impossible that anything other than dandelions would be found turned into a unique change of perspective on how a person could actually live off the land even in an urban forest when you discover that nature is urban. The simple act of looking for food in the city makes you look at the city differently and feel like you are a natural part of the city’s systems just like the food you find on your journey. The city is indeed a complex ecosystem.

Any advice for future urban agriculture enthusiasts?

Start small and plant a herb or edible garden that you can eat from to explore how it makes you feel to grow and eat your own food. Volunteer at a local community garden. Help a local school grow a food garden or a community start up a garden. Plant edibles in your next streetscape design or your own front yard. Use food as a platform to address design issues. Begin to utilize a systems thinking approach in all your work but especially in designing urban agricultural landscapes and you will be adding to the momentum towards a new more integrative city model. Decide that you, too can invite food back into your own city or town and forge a path towards creating healthier communities and a healthier environment. Think creatively and outside the box about cultivating this intersection of ecology, design and community. And don’t forget to take time to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

View more images from Designing Urban Agriculture

All images courtesy of author and Wiley

Member Spotlight: Interview with Bernard Trainor

With an impending publication and a constantly evolving practice, Bernard Trainor has a slew of interesting works in the pipeline. Bernard’s diverse background involves practicing in Australia and Great Britain, subsequently starting his own practice in San Francisco, California. His interest in the California landscape aesthetic continues to inspire others and create thought-provoking spaces. More after the jump…

How did you discover the profession of landscape architecture?

I really started as an apprentice gardener with my hands in the soil – this was extremely hard work and not particularly glamorous but it has made me aware of the climate, sites, and soils. What works and what does not has different consequences regarding my effort with a spade in my hands so this knowledge became a driving factor in my design work.

How would you describe your firm philosophy?

We look to the local identity and context, then create a simple and honest expression that relates to the place, the people, and the buildings. It sounds simple but the hard part is distilling down the information to appear as if there was no effort visible.

What inspires you and your work?

I would say natural environments are the biggest influence – just getting out there and feeling the power of a place that has evolved over many many years. I am enamored by the specifics details of a place that have essentially come about through necessity to survive. I find these patterns very beautiful when something is that way because it has to be.

Who inspires you?

I get to collaborate with some brilliant design minds on the teams for projects. Often I just sit and think how lucky to be at the at the table with these people – to be there to listen, strategize, and act on great ideas as a collaborator.

The people in the studio really come with creative ideas and a drive that constantly makes my mind tick, tick, tick, every hour of every day. They inspire me.

My daughters really blow my mind in how creative they are. There are moments where I think they are so far advanced in their thinking than I ever was. I enjoy watching them. This liberates me from the rut you can get in as an adult trying to be creative amidst all the rules and regulations we face every day.

You have a book that’s set to hit the bookshelves in April of this year. What do you wish for readers to gain most from this publication?

There is so much love that goes into the work by so many people over long periods to make these landscapes reality…I just want people to see the artistry of the design and the efforts of the many hands that touch the work.

It is really a privilege to have people allow us to shape the land they live on. I do not take this lightly and I hope this comes through in the work in the book.

How do your hobbies influence your work?

I think some of my favorite places to be is where the ocean meets the land – that meeting is where there is so much energy and influence in the patterns of water and land, tide and waves, rock and dunes, and so on. With this I enjoy water sports like sailing, surfing, kayaking, and perhaps, most all, just walking on a rocky beach. I feel best when I am around this force of land and water.

Your favorite place in the world is __________.

There are a few very special spots where I grew up on the Mornington Peninsula in South Eastern Australia, in particular a somewhat secret surfing spot called Central Avenue. Part of my memory of this place is that I had to scramble through the coastal dunes covered with Leptospermum’s and Banksia’s to get to the beach. This journey left a huge imprint on me in retrospect. This region is made up of some rugged coves and beaches around the small town of Blairgowrie – Just so many memories of being washed around on that southern coast trying to survive the surf!

So yes the Mornington Peninsula is a favorite…

If you weren’t a landscape architect, you would be a ______________.

I have always thought I could be a sculptor or a painter – even though I have no experience in this arena, I have a deep belief I could contribute something worthy in this area. I would work in a contextual, site specific way close to the land – I feel this is often missing from the work in the arts.

The other thing that I really am attracted to is stone, so maybe I would be a stone mason if I could survive the back breaking aspect. Stonemasons have my complete respect in the same way a great plants person does.

Plant personification time! If you were a plant material, you would be ________.

I would like to think I would be well shaped Manzanita in California or a nice tangled tea tree in Australia. I guess this is what I aspire to be in the plant world…

Even though you did not ask I would be happy to be a simple space covered with 3/8″ gravel if I were a hardscape material – Pretty sure of that.

So…maybe I am the manzanita growing out of the gravel? That about sums me up!

Where would you like to see the profession go next?

I have to say I think the change I have seen over the course of my career has been encouraging. Things have been moving along in a positive direction. This may be specific to my experience in that I work within a certain circle of solid practitioners. The mind set has shifted away from the chemicals, the lawns, and english garden lust in hot climates and over to a more regional and grounded approach to gardens. I am a proponent of celebrating where you live and I am seeing this from the best designers working for a more sophisticated clientele. The interesting work is not primarily budget-specific but it is being done by a group of thoughtful people who are aware of their place and happy to celebrate the local identity.

Please feel free to leave a comment below and share the interview on facebook and twitter… Thanks for reading!

Member Spotlight: Steve Martino

Land8’s next foray into Member Spotlightdom involves an interview with Steve Martino. Martino has been practicing for 30 years in the southwest United States. His work focuses on the vernacular of this more arid region, using native plant materials and xeriscaping while also celebrating the beauty of desert environments through concrete materials and strategic use of color. So without further ado, let’s meet this desert-inspired landscape architect!

How did you discover Landscape Architecture?

I first heard of landscape architecture in boot camp in San Diego, a guy in my platoon said he was going to be landscape architect.

When I was in architecture school I developed a strong interest in the project’s site work. I thought that it was such an important and integral part of a project that I couldn’t conceive of handing the site over to someone else to develop, lucky architects don’t think that way or we wouldn’t be in business.

My first job was with a landscape architect because I wanted to learn some landscape skills. This was my first critical look at the built environment, I was appalled at what I took for granted as a child growing up in the city. More appalling was the disregard for the desert environment. It was clear to me that nothing in the city was as interesting as the desert. I tried to bring the desert back into the city and was met with resistance from every direction which included municipalities, developers, home owners, nurseries and the landscape profession. I became an outsider with a chip on my shoulder determined to use desert plants. This was quite a struggle and I had to repeatedly tell myself that I was right and everybody else was wrong, in the long run I was right. Trying to get native plants accepted for their beauty and sustainability was such a long battle that I became side-tracked from becoming an architect. I had to develop the desert vernacular that should have been here.

What is your background?

I’m a college dropout. In 1966 I was an junior college art student when one of my professors suggested I visit Paolo Soleri’s studio in Scottsdale. I went on a Saturday when he was conducting one of his silt pile workshops, I was so impressed and taken aback with the atmosphere of his studio compound that on Monday I applied to the architectural school at ASU. A motorcycle accident after my 3rd year side-tracked me and I went to work in a landscape architects office to pay medical bills. I was later working and offered a job with an architectural firm which I took. Eventually the economy went bad and I had a few landscape projects as side jobs so I thought I’d try to make it as a landscape designer. To this day I have never had a landscape class of any kind but I didn’t let that stop me. I then went to work as a laborer in the only nursery that grew native plants in the state so I could learn about them and to ask the owner endless questions. later I had to have plants grown for my projects because they were not commercially available and this became my source for my plants, the owner an I became friends and went on several seed collecting trips into the desert and Mexico. I once read where one of my architect friends said that I had to build my stage before I could act on it and that was very true.

In the late seventies I applied to take the architects license exam and was told that I needed 2 more years of architectural internship before I could apply but I only needed one more year of work to apply for the landscape architectural exam. I was eager to have some kind of credential so I decided to go for it and bought a pile of books to study. Since I hadn’t gone to landscape architecture school I didn’t know what to study, I looked at my books and the only ones that interested me were the history ones. Out of frustration I decided to take the UNE exam just to see what direction I should apply my study efforts and to my surprise I passed the exam on my first attempt.

What has been your greatest challenge to date?

I think it’s a toss up between trying to change the direction of the profession or meeting payroll all these years.

What has been your greatest accomplishment to date?

I think it a toss up between changing the direction of the profession or meeting payroll all these years. Things have turned out different than I thought they would be. I thought that it would be difficult to get projects and to do good work. It turns out that is the easy part, what’s difficult is running a businesses and dealing w/ employees, taxes, insurance and building departments.

Who is one person that has influenced you?

Obie Bowman in architecture school. I was a first year student and he was a fifth year student, we became friends thru a sculpture class. His work so impressed me as to how thoughtful and artful architecture could be that it kept me in architectural school because I saw the potential of architecture. He was concerned w/ sustainable practices years before it became a general topic. Several of the architects I have worked with over the years have been more sensitive to the site and and environmental concerns than several of the landscape architects I have worked with.

Where do you find your inspiration?

From the site. the most important aspect of a project is understanding the site and then applying those lessons to develop a solution. To me design is just problem solving, the elegance of the solution is what makes a design good or just ordinary. When I first started in this field I could see that landscape design was a situation where someone could spend an enormous amount of money and when they were finished they still had all the problems they started with. If the designer doesn’t understand the site then his efforts are at best eyewash and at worst silly. I try to ground my projects to the site and relate them to the region I’m working in.

If you could work with any one person (past or present), who would it be?

Franklin D.Israel, my work was changed forever when started to see his work.

What trends are you seeing in LA, good or bad?

I think by their nature something that is a trend will not have a lasting value. I think the LEED thinking is insulting to us who have tried to have sustainable value in our projects as just a byproduct of the process rather than the driving force. It’s something developed by bureaucrats who need to make labels and tables to quantify results. I think it’s similar to the xeriscape trend where municipalities came up w/ a concept to protect themselves from the landscape architecture profession. Then to my amazement landscape architects would scramble to profess their xeriscape expertise.

Green walls are nice to look at but I can’t imagine they will be more than short term art installations. I think buildings covered w/ plants are creepy and look like something that has gone bad in the refrigerator. I don’t see what’s the big deal w/ green roofs they have been around for centuries.

I really hate large areas of plants in geometric patterns that are meant to be a design statement, I rather see that energy spent on some clever way to restore the habitat that was destroyed in the name of art or landscape architecture. what I see as good ls turning industrial sites into livable space. The High Line project is a great example as is opening up waterfronts for public access and use. As a country i think we are late to the table on rain water collection systems but we are getting it. Finally I like the fact the use of that native plants has become more popular.

If FLO was alive today, what would he think of the profession?

I think he would be disappointed that it took the profession so long to get on board with environmental issues. I think he would say “”landscape architecture that was so 100 years ago”” because I assume he would have gone off to tackle greater social issues and probably would have been president of the USA along the way.

What’s your favorite material to use?

Concrete block, all my projects have relied on this material.

What’s your favorite color?

Rust.

Where is your favorite place to eat?

Barcelona

Who is your favorite contemporary designer?

Michael Van Valkenburgh

My favorite ____ is ______.

day is Saturday

What advice do you have for students and those entering the profession?

You need to understand how difficult of a profession it is, you are at the mercy of the economy and the construction industry unless you choose to work for a government agency. I have had lots of wonderful clients, opportunities and successes but on the other hand this is my 6th recession. There has been years that I would have earned more as a check-out clerk at Safeway.

I love design, problem solving and the opportunity to create something wonderful where there was nothing before. You need to have a passion for the profession if you want to stay in it and be happy. An important thing to know is that as a designer you have the opportunity to make your own projects. An example of this is my entry design for Arid Zone Trees, the client came to me for a gate design to his farm. I gave him his gate and added an environment to go with it that addressed some environmental issues. the project won numerous awards including a national ASLA honor award. Small projects can become significant gems and have an impact.this demonstrated that you can make a small project into something beyond just the progarm requirements if you choose to.

Anything else that you would like to add?

What I like about being a landscape designer is that I get to work with trees, plants, dirt, water, stone, fire, sun, darkness, wind, sound, lighting and any architectural material to create livable outdoor spaces. How else could you do that?

Receive the latest from Land8 via email: http://goo.gl/fEvxo

Interview with Andrea Orellana

Andrea Orellana is a landscape designer who, as she says, “swims against the stream”. She has a Bachelor of Science and Environmental Studies from the Central University of Chile. Andrea is the founder of Paisajismo Interior, a corporate website that has evolved into a diffusion and transmission website of landscape architecture and environmental topics. The website involves the contributors’ work and is based in Chile. Andrea is passionate about technology and the reutilization of all present elements and native flora in her projects.

Andrea, thank you for allowing Land8Lounge’ers to learn more about your perspectives about landscape architecture in Chile!

Thank you for your interest in a landscape designer in the other side of the world.

What were some of the most valuable lessons that you learned in your program at Santiago, Chile, and how have you been able to use these lessons in your professional life?

Insight. Knowing the best medium and where it is going to be located and its intervention, since the point of view of the landscape designer is being capable of seeing what other professionals can’t appreciate or do not understand. This basic rule has been the most useful and advantageous to me, making me always be careful to view all points that can be affected in the future. We have been taught that we are the only professionals capable of speaking with an architect, biologist, geographer and designer at the same time and understand their points of view.

What types of projects have you been able to work on at Paisajismo Interior?

At the moment, Paisajismo Interior is in a process of creation, doing several private garden projects. At this time I’m developing a master plan and biological corridors over the island hills in the city of Concepción, Chile. Besides those, the website works as a diffusion and transmission media about landscaping and environmental topics in Chile, a kind of environmental education online which works with the contribution of an engineer in Renobables Resources (Universidad de Chile), a geography student (Universidad de Concepción) and me, with a Licenciada en Ciencias y Artes del Medioambiente (Bachelor of Sciences and Arts of Environmental Studies) and Ecóloga Paisajista (Ecologist Landscape Designer).

Are there any local projects in Santiago that you have found inspiring?

I like the Bicentennial Park in Vitacura, Santiago which is designed by Teodoro Fernández and located south of the Mapocho river, extending across Santiago. The park integrates the most important milestones of the city (The Andes mountain range, Mapocho River, Saint Cristobal hill) by the means of simple and modern lines which freshen the park concept and broaden the entire city. It is one of the most innovative parks that exist in the city. There is also the Andre Jarland Park in the Pedro Aguirre Cerda commune in Santiago. The distinctive feature of this park is that it is the first park to be built over a landfill in Chile. It needed an immense amount of initial work to prepare the ground and now it has been operational for 15 years without any inconvenience. What was once a ruined and forgotten area of the city now gives value and identity to the locality known by its mainly low socioeconomic status population.

Where would you like to travel and what would you most like to see?

I would like to visit New York to learn in depth about the High Line project.

You and me both! And finally, what are your favorite things to do in Chile? What should fellow Land8Loungers should they chose to visit Chile?

Uf! In Santiago everyone should see The Andes after a rain is staggering, milky white, magnificent and ravishing.

Pay a visit to the south of Chile and their National Parks. Their amount and diversity of forests and native flora is awe-inspiring because it adds to the special value of its biodiversity unique to the world. You could hike all of the parks.

Also, drop by the driest desert in the world that is capable of blooming with a series of native species. “El desierto florido” is a unique climatic phenomenon that occurs only in the Atacama Desert.

Book Review: The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems

Lately there has been a lot of hype about what it means to be “green” and to “live sustainably”. The green message is omnipresent: celebrities are touting their electric cars, models are strutting down the catwalk in organic clothing, Ed Begley Jr. and Bill Nye are competing on a reality television show to see whose house can be more eco¬friendly. But one has to wonder how much of the green message is encouraging actual changes in energy savings in American households, and at what pace? There is a message, yes, but is there action? And to whom are we sending the message?

One of the organizations that is soaring into the green activism forefront is Green For All, which “advocat[es] for local, state and federal commitment to job creation, job training, and entrepreneurial opportunities in the emerging green economy – especially for people from disadvantaged communities”. Green for All focuses its message on those who might not walk the red carpet at the Oscars, but rather those who are striving to survive paycheck to paycheck. As such, the Green for All intent is to bring awareness to green collar jobs and their potentially critical role in the future of the American economy and global environment. Van Jones, founder of Green for All, has been urging the organization’s message through his book, The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems.

In The Green Collar Economy, Jones stresses the importance of recognizing America’s two biggest hurdles to tackling the climate crisis which are radical socioeconomic inequality and rampant environmental destruction. Jones recommends a more inclusive message when teaching Americans sustainable practices since it is evident from examples like Hurricane Katrina that the poor are the first to suffer in an environmental catastrophe. Likewise, it is these same individuals that could prosper most by switching from blue-collar jobs to green-collar jobs due to the inevitable demand for workers in the production of clean energy mechanisms.

The tone of The Green Collar Economy is that of urgency. Jones cites past environmental movements that occurred at crucial times such as John Muir’s fight for the preservation of national parks and Rachel Carson’s conservationist movement. While these movements spurred significant advances in litigating the protection of environmental resources, the movements focused more on the environmental problems than on the resulting plight of the lower socioeconomic classes. The inclusion of individuals of all races in the future environmental movement needs to happen now, or else the already dire condition of the world’s environment will take an even more haphazard downward spiral.

More than anything, reading The Green Collar Economy will inspire one to get involved and active in this next wave of environmentalism. Jones encourages wholehearted inclusion over myopic exclusion, sincere activism over aloof passivity, and diligence in seeing through the prospect of what green jobs can offer the American economy.

**For those interested in tackling climate change by way of the Green for All message, see http://www.greenforall.org/, and http://www.greencollareconomy.com/.**

Interview with Susan Cohan

Susan Cohan, APLD is a certified landscape designer. Her practice specializes in residential landscape design in the NY metropolitan region. Susan’s work has been featured in traditional and digital print as well as other media outlets. Her blog Miss Rumphius’ Rules features work in progress, musings on the creative process and insights on design, she also edits the APLDNJ blog and is passionate about Social Media. A founding member of the NJ chapter of the Association of Professional Landscape Designers (APLD), she also serves on its International Board of Directors as Membership Chair.

Susan, first of all let me commend you for bringing recognition of the APLD (Association of Professional Landscape Designers) to Land8Lounge. I understand that you are the founder of the APLD’s New Jersey chapter. What exciting events are planned for your chapter this year?

Actually, I was only one of several founding members of APLD’s NJ Chapter…3 others that I know of are Land8 members: Laurel Aronson, Susan Olinger, APLD, and Whitney Freeman-Kemp—there could be one or two others that I don’t know about—so if I’ve missed them I apologize! The NJ chapter is growing and like the larger international association, we focus on events that landscape designers can use to add to or augment their skills and knowledge professionally. Some events that are being planned in NJ are a rainwater harvesting workshop this summer and in the fall we have two—one on garden photography and another about developing effective working relationships with contractors. All of the chapters have great programs geared towards all levels of landscape design experience and this summer is also APLD’s annual landscape design conference in Portland, OR. We’re really busy as you can see!

You have a background in fashion design. Can you articulate how a background in a certain design field can parlay into many other realms of design? What lead to your switch from fashion design to landscape design?

It might seem like a cliché, but great design translates across disciplines. The tools are different but the basis of all design problems is the same—a given set of criteria defines and drives the process. Artists start with a blank canvas, designers start with a series of problems to solve. My years in the fashion industry trained be to be observant and aware of all of the influences a design might have, and to not focus on one thing—to look at everything from emerging trends to pop culture to color to materials to history to influential designers in other fields as well as your own. It also taught me to embrace new technology as a means to enhance the creative process. I think many landscape designers are afraid to do this.

I made the switch to landscape design because I wanted to do something new that would draw on all of my experiences to that point. I needed a challenge intellectually and creatively and I wanted to work outside of New York City where I had been working for years. I have always gardened—since I was a child actually. I have also always been drawn to the larger landscape both as a source of inspiration and as a source of personal and creative renewal. It seemed to be a natural evolutionary process in my development as a designer. What surprised me, however, is how much of my past experience I apply on a daily basis to my current practice.

You seem to be quite the Renaissance woman! In addition to your activity with the APLD and being the owner of your own landscape design firm, you also blog about design on missrumphiusrules.blogspot.com. What was the inspiration behind your blog site and what would you like readers to gain from your writings?

Although I appreciate the complement, I’m not really a Renaissance woman, Miss R is written really just for me—another facet of a creative life lived. I love to write and the blog is an outlet for that. Often, the writing helps me clarify a thought or an idea that I have. Since the focus of the blog is on my own creative process within the confines of a landscape design practitioner, I have a lot of leeway to explore different ideas. I hope that Miss R—my alter ego–gives people a small window into how I (and maybe other designers) think and solve problems. It’s not a garden blog, and because of that, it doesn’t fit neatly into many people’s criteria for what they think I should be writing about–it’s a really a public journal. It has a small, loyal following.

I also edit the new APLDNJ blog at http://apld.wordpress.com which is the virtual portal for the NJ chapter. There’s been a lot of interest there in the social media posts and virtual events we’ve been blogging about. I’m passionate about the integration of social media into the landscape design marketing matrix.

It seems that your firm website places an emphasis on the design process. What sorts of experiences have lead to this firm acknowledgement of process in your projects, and how do you try to help clients understand this important part of successful design?

As you know, I specialize in residential landscape design. So, ultimately, I walk away from a project and it becomes an environment for someone else to live in. I involve my clients in their land’s design before they even meet me. I send them ‘homework’ prior to our first consultation so they understand from the onset that I expect their participation in the process—beyond writing the checks.

I believe there are parallel drivers to my work. First, the land—it will tell you what it wants to be if you listen and second, the client will also tell you what they want it to be. My job is to fuse those two ideas into a cohesive whole. If I am successful, then every project will be unique to its environment and will give each client a new appreciation for their land and its use. I always try to compel my clients to use their land in ways they may not have thought of—whether it’s through necessity or destination.

What were some of the most useful lessons that you learned when studying abroad at The English Gardening School at the Chelsea Physic Gardens in London?

I actually began my study abroad after graduating from art school in the 70s at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in France. I was too young to fully appreciate the experience. So that by the time I decided to study landscape design, I’d been involved professionally in various design disciplines for 20 years. I had also taught design at the college level and had a highly developed personal aesthetic. Because I wanted to switch disciplines I felt what I really needed were the specifics—a jump start on the technical aspects of the discipline and the finer points of making drawings that contractors could read. I also wanted a marketable education since I wasn’t sure anyone would be interested in my previous experience.

At the time, unlike now, there wasn’t a part-time program available that I could work with. I looked into the landscape design program at NYBG, but the commute was too long at night—I was working full-time. I wanted to explore landscape design program alternatives so on a trip to London I went to speak to the dean of the English Gardening School. They had a traditional via mail distance program that had been set up by Rosemary Alexander, so I actually did my work here with a great mentor from the EGS, Gillian Lotter, mailing and emailing back and forth. She really challenged me throughout the 18 month long process. I continue to learn and have to earn CEUs to maintain my APLD certification.

Any advice to the fledgling firm starters out there on Land8Lounge?

Be passionate about what you do. Get great business advice and if you haven’t, work at a nursery and/or for another designer and learn your plants and their best practices. School is great, but often impractical and unrealistic. Understand that as a designer, without clients who are satisfied with the work you do for them, you can’t work and that your work is really theirs—it’s a difficult lesson. Realize that a creative life is just that—your life—it’s not just a 9-5 job.

I think in closing I’d like to thank Land8lounge for including landscape designers in the on-line community. We all need to work together to sustain, protect and add to our planet’s great bounty and beauty.