Author: Mark Harrison Hough

Fallingwater: A Must-see for Landscape Architects

Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s celebrated masterpiece located a little over an hour outside of Pittsburgh, is one of the most famous houses in the world. Over five million people have visited the property since it was opened to the public in 1963. I added my name to that list once again when I visited recently for the first time in nearly 20 years. As before, I was not disappointed. If you haven’t been there, you need to go.

Architects have long considered Wright one of their biggest heroes, and Fallingwater one of their most revered places. We landscape architects have our own list of hallowed sites, including Prospect Park, the Miller Garden, Sea Ranch, Bryant Park, Gas Works Park, and many others. While we typically like to see places designed by other landscape architects, Fallingwater deserves to be high on our list, as well. For as great as the house is, it is the extraordinary relationship between building and site that makes the place so special.

A lot of of Fallingwater’s success can be attributed directly to its setting. Nestled in the lush wooded hills of rural western Pennsylvania along the Bear Run waterway, it is the epitome of picturesque. Wright based his design on his theory of organic architecture, where the design of buildings is directly informed by the qualities of their sites. “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything,” he once said. “It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.”

While this way of thinking certainly seems logical to landscape architects, architecture during the 1930s, when Fallingwater was designed and built, was teetering between the “master builder” mentality of the Beaux Arts era and the anti-context mindset of the Modernists. Art Deco was big and architecture was a lot about new materials, technologies, and ego.

While this way of thinking certainly seems logical to landscape architects, architecture during the 1930s, when Fallingwater was designed and built, was teetering between the “master builder” mentality of the Beaux Arts era and the anti-context mindset of the Modernists. Art Deco was big and architecture was a lot about new materials, technologies, and ego.

RELATED STORY: TCLF Spotlights Dan Kiley’s Endangered Landscape Architecture Legacy

This is not to say that Wright’s famous ego was not involved in Fallingwater. Examples of his megalomania are all over the place inside the house, seen in his overindulgent insistence on self-designed furniture and fabrics. Actually, I could skip the whole house tour entirely, except it does give you access to the wonderful terraces and hits home just how important integration to the site was to the design of the building. Views and access to the outdoors are carefully orchestrated with cleverly designed windows and an ingenious trap door of sorts that leads you directly to the water below.

This is not to say that Wright’s famous ego was not involved in Fallingwater. Examples of his megalomania are all over the place inside the house, seen in his overindulgent insistence on self-designed furniture and fabrics. Actually, I could skip the whole house tour entirely, except it does give you access to the wonderful terraces and hits home just how important integration to the site was to the design of the building. Views and access to the outdoors are carefully orchestrated with cleverly designed windows and an ingenious trap door of sorts that leads you directly to the water below.

Wright has been both lauded and lambasted for his decision to site the house atop a waterfall – with no direct view to it from the inside. By cantilevering the structure across the falls, he makes it part of the natural world rather than a vehicle for observing it. For me, this works. We’re not talking Niagara here. It is all fairly modest, and by incorporating the noise and movement of the water into the house, it creates a synergy that is essential to the overall design.

Wright has been both lauded and lambasted for his decision to site the house atop a waterfall – with no direct view to it from the inside. By cantilevering the structure across the falls, he makes it part of the natural world rather than a vehicle for observing it. For me, this works. We’re not talking Niagara here. It is all fairly modest, and by incorporating the noise and movement of the water into the house, it creates a synergy that is essential to the overall design.

RELATED STORY: Waterfall Garden Park | Seattle, WA

There are examples where Wright could have used some advice from a good landscape architect, however. The pool at the guesthouse, for instance, is, at best, awkward. What could – and should – have been a well-integrated feature reflecting either the layered horizontality of the building or the natural flow of water through the site lands blandly in between in the form of a clunky, concrete above-ground pool. It is really bad. Unfortunately, it is on part of tour where you can’t take photos, so you will have to take my word for it or, better yet, see it for yourself.

Even with this, however, it is hard to do anything but applaud his efforts. To be clear, I am not some Frank Lloyd Wright fanatic. In fact, I have been underwhelmed by more of his buildings than I have loved. An obvious exception to this is the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, which, in its own way, responds to the urban context of the Upper East Side of Manhattan in a manner as elegant as Fallingwater’s response to its natural setting.

In the end, it should not matter that Fallingwater was the vision of an architect and not a landscape architect. We should all aspire to create places that understand and effectively respond to both the built and the natural. That is, in essence, what landscape architecture is all about – and the more we can make architects see that, all the better.

In the end, it should not matter that Fallingwater was the vision of an architect and not a landscape architect. We should all aspire to create places that understand and effectively respond to both the built and the natural. That is, in essence, what landscape architecture is all about – and the more we can make architects see that, all the better.

All photos by Mark Hough, taken July 14, 2014

Does Beauty Still Matter?

There was a time, not too long ago, when the quality of urban landscapes was determined by what they looked like and what it was like to be in them. Their ecological and human health benefits were well known, but these were seen mainly as positive by-products of what was more important: improving the quality of life for people living in cities by providing them with access to nature, or at least some semblance of it. The desire for urban parks was rooted in a simple, yet deep appreciation for the beauty of landscape.

These days, however, even as the urban landscape has a higher profile than ever before–thanks in part to grand new parks in cities such as New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and Los Angeles–it seems less and less acceptable to evaluate such places merely on their aesthetic or place-making merit. As is made apparent in countless blogs and publications focused on urban design, landscape architecture and even architecture, the conversation surrounding parks and other city landscapes is changing. You can’t use poetic terms like picturesque to describe them anymore; they have to be labeled something like resilient or high performance if they are going to be taken seriously.

RELATED STORY: The Beauty of Food: Gardens As Placemakers

There are, of course, legitimate reasons for this – climate change being an obvious one. The national discussion that took place following Hurricane Sandy showed a new awareness of the issue. The fragility of coastal cities became a popular topic and people were perceiving urban landscapes in a new way. As droughts persist in some areas and powerful storms are becoming the norm in others, it is clear that the status quo is no longer a viable option when it comes to planning and building communities.

Fountain Place in Dallas, photo by Mark Hough

Fountain Place in Dallas, photo by Mark Hough

Because of this, planners, engineers and designers are busy figuring out new ways to prepare for and mitigate the next disaster. Landscape architects are a big part of this and are relishing the opportunity to show what they are capable of. Many of them have stepped up, either on their own or as parts of larger teams, with complex proposals for at-risk urban landscapes, and are getting a lot of attention for them. Where in the past this work might take the form of beautifully rendered planting plans and evocative imagery showing what a place will look like, what we are seeing today are highly technical and scientific-based proposals. Beauty may still be a goal, but is increasingly hard to find within all of the diagrams and flow charts.

The shift in focus to a more technical perspective on landscape goes back well before Sandy. Influential sustainability ratings programs such as LEED have been around for over a decade now and continue to play a big role in this. The effect of these programs has probably been more apparent with architecture, as the ultimate goal of creating buildings with beautiful façades has given way to a need to make them as energy efficient as possible. This has undoubtedly changed the look of contemporary architecture.

Even with that change, however, I would argue that the effect of all this has been even more significant on the landscape. The prescriptive and generic methodologies endorsed by LEED and other point-grabbing systems deny the flexibility landscape architects need to effectively deal with the specifics of a given site and the unpredictability of its natural systems. Ratings programs are so often building-centric and take such a narrow view of what performance in the landscape means that factoring in what they will actually look like has been nearly impossible. There is hope that the impending introduction of the landscape-focused Sustainable Sites Initiative will help with this, but, even so, a corner has been turned, and beauty may never again be the barometer by which to assess the success of designed landscapes.

The Dell at the University of Virginia, photo by Mark Hough

The Dell at the University of Virginia, photo by Mark Hough

I am by no means suggesting that beautiful places are not being created these days; they certainly are. Most landscape architects currently working were trained in a tradition that celebrates the connection between the profession and the fine arts, and their work reflects that. I am more worried about students and young professionals coming up now who are being eagerly coaxed into a realm of resilient landscapes, where ecology rules over aesthetics, and what is being produced looks promising on paper but remains largely untested in reality. As inspired as I am by their idealism and captivation with the potential to play a role in solving global problems, I can’t help but wonder if designing parks or plazas with the meager goal of creating wonderful places for people to use will even interest them.

RELATED STORY: Beauty on a Budget: Landscape Architects EMF Transform Urban Wasteland into Barcelona Pocket Park (LINK)

The design process inevitably evolves over time, as do people’s expectations of beauty. We are now in an era driven by a mandate to design and build in an environmentally responsible manner. While that is not in question, nor should it be, how best to do that should still be open for discussion. If the design of landscapes continues down the path of being dominated by a dictated requirement to meet metrics and provide measurable data, we will be left with less room for discussion about intangible things like beauty – which may seem frivolous to some but is critical to the quality of the urban environment.

Tuileries Gardens in Paris, photo by Mark Hough

Tuileries Gardens in Paris, photo by Mark Hough

Design may seem more legitimate when all the components can be systematically quantified, but doing so does not necessarily translate into the creation of better places from an experiential perspective. We can all agree that urban landscapes are increasingly important as ecologically charged tools for soaking up sea water, cleaning the air and adding mass to carbon sinks, but that does not mean their value as sources of inspiration and intrinsic parts of human life should become less of a priority. If that is allowed to happen, cities will inevitably suffer.

Lead image of Conservatory Garden in Central Park, Photo by Mark Hough

‘Does Beauty Still Matter?’ was first spotted on Planetizen.

NLAM Career Discovery: The Campus Landscape Architect

In the spirit of ASLA’s promotion of career discovery for National Landscape Architecture Month, I want to give some insight into an important segment of the profession that is not talked about very much: the campus landscape architect. Landscape architects have been working on college and university campuses as design consultants for over a century, but in this other role – working in-house for the schools themselves – they are increasingly making big differences in the long-term stewardship and transformation of these important places. If you are interested in landscapes that are both historic and dynamic, and like the idea of making a significant impact on one special place, then I can’t recommend this career path highly enough.

Before I was hired on as Duke University’s first campus landscape architect fourteen years ago, I had already cultivated an interest in campus design in graduate school, but did not act on it right away. After graduating, I tried the design firm route for a while, but quickly realized that I wasn’t satisfied with designing far off places that I knew I would never experience in real life. A stint at the Central Park Conservancy in New York City, however, gave me a deeper understanding of the value of landscape stewardship and strengthened my resolve to work and live in a campus environment, which eventually led me to where I am today.

New Campus Master Plan, Duke University, with Reed Hilderbrand and Pelli Clark Pelli Architects

New Campus Master Plan, Duke University, with Reed Hilderbrand and Pelli Clark Pelli Architects

University campuses are complex and dynamic places – like microcosms of entire cities, only with a much higher percentage of green space. In my role, I oversee everything outside of the buildings, including site design, pedestrian and bicycle circulation, wayfinding, transportation systems, sustainability, historic preservation, ecosystem conservation, stormwater management, and the overall aesthetic of the landscape. I make sure the campus evolves in a way that simultaneously respects its historic legacy, successfully integrates contemporary design expression, and incorporates responsible design and maintenance practices that support the university’s commitment to sustainability.

Stormwater Reuse Pond, currently under construction, Duke University, with Nelson Byrd Woltz

Stormwater Reuse Pond, currently under construction, Duke University, with Nelson Byrd Woltz

While I do not handle all of the detail work by myself – I engage design firms to do most of the big projects – I am involved in the decision making when it comes to what actually gets planned, built and preserved. Most of the work involves intensive collaboration, not only with the firms, but also with students, faculty and others in the university community. This is part of what makes the work so rewarding. Over the past several years, I have had the opportunity to work on campus projects with Laurie Olin, Warren Byrd, Gary Hilderbrand, Michael Vergason, and other talented landscape architects– there are not a lot of jobs that let you do that! I help them understand context and big-picture goals for the university, collaborate on design schemes and help them navigate what can often be a confusing process. The campus landscape architect provides assurance that all projects are tied together in a cohesive way and meet broader goals set for campus development.

Medical Center Quad, Duke University, with OLIN, photo by Mark Hough

Medical Center Quad, Duke University, with OLIN, photo by Mark Hough

Not all schools have in-house landscape architects, and those that do place them in different roles in various forms of planning and design offices. Because of this, finding your way in the campus job market may not be as direct as with traditional firms or even city parks or planning offices.

Related Story: The Power of Landscape Architecture on the American College Campus

Eva Rose Leavitt, for instance, who is a landscape architect at Stanford University, stumbled upon her job almost by accident in a move she calls “serendipity.” She learned of an entry-level position opening in the Campus Planning and Design office while attending a student outreach meeting for the UC Berkeley Extension program. Intrigued, she applied and was hired.

“I love watching work get built and seeing how the students, faculty and staff use and live in the spaces that are created,” she says. Working in campus landscape architecture offers the opportunity to be part of the whole lifecycle of a project, from design and construction to observing how the space ages day by day. This level of involvement is usually not the norm at most private landscape architecture firms, where designers often move on from a project once construction is complete. “You can learn so much more from being around to see things change,” Leavitt says. “The ability to tweak and refine things so that they succeed is very precious.” This is, in essence, what landscape stewardship is all about: not taking photos once a project is built, but helping places grow and evolve over time.

Penn Terrace, Duke University, with Reed Hilderbrand, photo by Mark Hough

Penn Terrace, Duke University, with Reed Hilderbrand, photo by Mark Hough

As wonderful as I think the job is, I also recognize that it is not for everyone. People with tender egos might resent having their ideas and decisions credited to consultants or others in the university, which sometimes happens in such a collaborative environment. However, for those with a big picture perspective, an appreciation for the interplay between history and contemporary design, and the patience to wait for the transformation created by the many moves, there are few jobs as rewarding as being a campus landscape architect.

Related Story: April is National Landscape Architecture Month!

West Campus Plaza, Duke University, with Hargreaves Associates, photo by Mark Hough

West Campus Plaza, Duke University, with Hargreaves Associates, photo by Mark Hough

Lead Image: Duke University West Quad, design by the Olmsted Brothers firm, photo by Mark Hough

The Power of Landscape Architecture on the American College Campus

Landscape architects – and I include future ones in this group – seem obsessed with cities these days. Urban projects are all over the place at conferences and in design magazines, and even more predominate in related social media and the blogosphere, to the point that it makes me wonder if we all really just want to be urban designers. Of course there are legitimate and good reasons for this focus, such as the fact that more work is becoming available in cities as people migrate back from the suburbs, and high profile urban projects give landscape architects greater exposure on the media map.

Even so, I do worry a little that this preoccupation with big city landscapes may limit the perspective of students and young professionals to just how vast and diverse this profession really is. Although I won’t address all the possible career paths for landscape architects here, I do want to point out a specific and important segment of landscape architecture that rarely gets much attention: the campus landscape.

Harvard Yard Restoration at Harvard University by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, photo by Mark Hough

The college and university campus is a cherished and integral part of the United States’ collective history, culture and physical landscape. As an image, it embodies the potential inherent in education. More importantly – at least in this context – the campus, as a place, represents for many their first home away from family, and shapes how they experience the world. This bond between people and place is strong enough to last a lifetime. That enduring relationship is also a big reason why the campus is so important to the profession of landscape architecture.

The history of designed campuses in the United States goes back long before landscape architecture was established as a profession. Once Olmsted arrived on the scene, however, he quickly made campus work a big part of his practice, as did many of his contemporaries and those who followed behind them. As the campus landscape architect for Duke University, I always assumed that the reason why campuses were often kept out of today’s conversation was because of its long history and tradition – as if it was deemed not cutting edge enough. It is precisely the campus’ long tradition in American culture, however, and how it works in tandem with progressive ecological practice and contemporary design expression, that makes the campus such a challenging and intriguing landscape typology.

Historic Quad Restoration at the University of Chicago by Hoerr Schaudt, photo by Jason Smith

The campus plays a critical role as the physical reflection of a university’s commitment to simultaneously preserving its historic legacy while accommodating a near constant need to grow and plan for the future. The recent and ongoing restoration of historic campus cores at schools such as Harvard (with Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates), University of Chicago (Hoerr Schaudt), and Duke (Reed Hilderbrand) reflect the more traditional side of the discipline, but is increasingly juxtaposed against a wide variety of new contemporary landscapes being created on campuses across the country.

Memorial Stadium at UC Berkeley by OLIN, photo © LAND COLLECTIVE

Such contrast between past and present turns campus landscapes into canvases upon which the evolution of our profession can be seen. In Stanford’s campus, for instance, visitors can experience one of Olmsted’s earliest Beaux Arts-inspired landscapes, walk through spaces designed by modernist greats Garrett Eckbo and Thomas Church, and then see contemporary places created by Peter Walker, Tom Leader, SWA, Cheryl Barton and Hargreaves, among others. Certainly not all schools have such a rich pedigree, but many have their own impressive variety of spaces designed by generations of great landscape architects.

Shoemaker Green at UPenn by Andropogon Associates, photo by Andropogon Associates

It’s not just about design, though. Pedagogical missions directed toward environmental sustainability have fundamentally changed how schools look at their landscapes. Nearly 700 college and university presidents have signed the Presidents’ Climate Commitment, pledging their schools as leaders “in their communities and throughout society by modeling ways to minimize global warming emissions, and by providing the knowledge and the educated graduates to achieve climate neutrality.” This means that sustainability is now a fixture in all decisions and discussions for architecture, engineering and, of course, landscape architecture, where transportation demands, landscape management, stormwater management and an emphasis on native ecosystem design all come together in a rich and complex system.

Arizona State University Polytechnic Campus by Ten Eyck Landscape Architects, photo by Bill Timmeman

There are recent projects in all parts of the country that exemplify a new type of campus landscape, including higher profile ones such as the Dell at the University of Virginia (designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz), Shoemaker Green at the University of Pennsylvania (Andropogon Associates), the Polytechnic Campus at Arizona State University (Christy Ten Eyck), Memorial Stadium at UC Berkeley (OLIN), the Medical School at Stanford (Tom Leader), West Village at UC Davis (SWA), the Brochstein Pavilion at Rice (James Burnett), and many more. They may not be the sexiest projects around, but the work being produced for college and university clients is high quality, imaginative and exemplary of what makes the profession of landscape architecture so diverse and wonderful.

The Dell at the University of Virginia by Nelson Byrd Woltz, photo by Nelson Byrd Woltz

The Dell at the University of Virginia by Nelson Byrd Woltz, photo by Nelson Byrd Woltz

Lead image: Li Ka Shing Center at Stanford by Tom Leader Studio, photo by Tom Leader Studio

Green Urbanism is the Future! Well, Maybe.

The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) recently announced the winners of its annual awards program, honoring the best of the best (at least in the juries’ opinions) in both professional and student work. My guess is the glossy, beautifully photographed images showing built work designed by professionals attract the most attention. But for me, even though I appreciate design eye candy as much as anyone, my focus inevitably shifts to the planning and analysis category and, in particular, the student work, because it is here, in the unrealized work, that we catch a glimpse of where things are headed or, perhaps, should be headed.

The planning award winners include a waterfront makeover for Seattle, a couple of major urban improvement projects in China, a cool proposal for incorporating public art to ameliorate the dreadful monotony of the sprawling corridor through Atlanta, and, most exciting to me, a next step in the planning for the revitalization of the Los Angeles River in LA, which by now seems to have been in the works for forever.

Image: Mia + Lehrer Associates

That project, led by the Los Angeles-based landscape architecture firm, Mia Lehrer + Associates, is another example of how “green urbanism” is catching on in major US cities – a trend that has been amped up by very real examples of the effects of climate change such as “Superstorm” Sandy. More of these types of projects will undoubtedly be seen in this category in the next couple of years, likely coming from recent initiatives such as the Rebuild by Design competition. Time will tell how much of this planning and analysis actually gets translated into built work in the future, but it is fun to look at in the meantime.

Along that same line, since the student awards are even that much further removed from the restraints of reality, they are often more intriguing. With titles such as Dredge City: Sediment Catalysis, Natural Water as Cultural Water / A 30 Year Plan for Wabash River Corridor in Lafayette, Re-transforming Landscape at the Arroyo Seco Confluence, and METABOLIC CHANGE: Coastal Patterns of Human Settlement and Material Flow, it is not too hard to see that broad, environmental, climate-related issues are resonating with students today.

Image: Daniel (Zhicheng) Xu, Purdue

It would be wrong to assume that these (or any) award winners portray the breadth of what is being taught, and should not be interpreted as such. However, these projects do become the standard bearers for quality work being produced by landscape architecture programs – as self-selected by faculty and students, and then as recognized by a jury. The big takeaways for me from the student awards are:

Idealism is alive and well.

Nearly every awarded project conveys the optimistic surety that ecologically responsible design and planning can vastly improve both human and natural conditions. Although most of the human part of that equation is sadly lost amid all of the data and snazzy graphics, I am far more willing to let it slide here than I would be with professional awards. The important thing, as I see it, is that these students are deeply engaged in, and apparently energized by, the realization that there is an unbreakable connection between people and landscape – whether urban, rural, cultural or natural – that can be either for the betterment or detriment of both. Landscape architects, they have learned, can play a critical role in determining which will be the case.

The inevitable problem with this kind of idealism is that it can have a tough time holding its own against the hard force of reality. Students leaving school with ambitions of saving the world can become discouraged by the ho-hum tedium of life as an entry-level grunt. Because of this, teachers and employers should equally shoulder the burden of preparing students for potential disappointment, while allowing them to maintain their ideals, even through the mundane, as they work their way toward making a real difference.

Image: Leonardo Robleto Costante, PENN

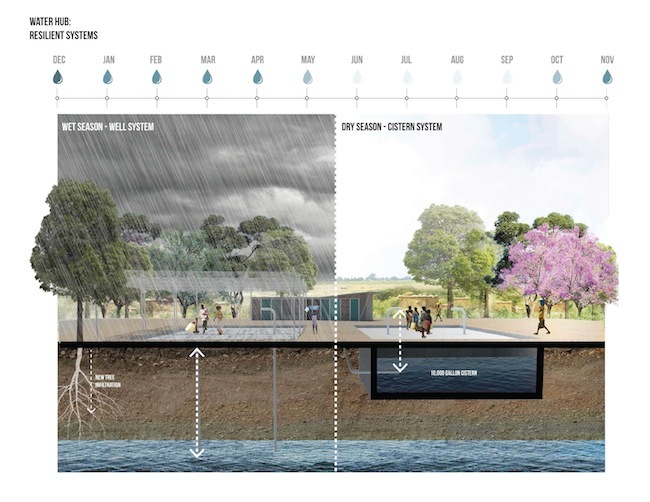

Water rules.

With a few exceptions, water is the big focus with the student winners. This is not surprising, really. Landscape architects have been pushing their qualifications as being the best to deal with the ecological, human and aesthetic aspects of water and stormwater management for a long time, lately under the guise of “green infrastructure.” The visceral impacts left behind by Hurricanes Katrina, Ike, and Sandy, along with other types of increasingly intense storms, continuing widespread drought, and sea level rise, have fueled this interest and made water a logical subject of focus. That’s a good thing. The challenge I see, however, comes with making sure the experiential aspect of place-making does not get lost among the detailed complexities inherent in ecology and climatology. I fear this may already be happening on some level, as:

Traditional, design-based landscape architecture has gone AWOL.

Small scale, site-specific design has been nearly impossible to find in the student award winners over the past few years. This does not necessarily mean this work is not getting done, just that it is not considered the most award-worthy. Which is fair. Since much of this work is driven by the research and interests of faculty striving to keep their classes relevant, more cutting edge subject matter naturally takes some priority. Students are obviously being pushed to think critically about contemporary, big picture things, but are they learning how their conceptual solutions might ultimately be implemented? I hope so, since landscape architecture is still a profession rooted in design and construction, and a big part of the value landscape architects bring is their ability to get things built.

Which brings me back to the eye candy. When you compare what wins for student and planning awards versus the built project winners – in this case a cemetery, a section of the High Line, a corporate campus, a waterfront park, residences and a garden, among other projects – it is like night and day. The source of this disconnect is not about any lost sense of idealism; it is about what clients are willing to pay for (and how well it photographs). Until they get built, fantastic and important work, such as Lehrer’s project for the Los Angeles River, remains merely plans on paper.

The fact that something is the right thing to do does not mean it will necessarily get done. That does not mean we stop trying, or stop awarding vision.

Mark Hough Bio:

Mark is the campus landscape architect at Duke University. He has been involved in all aspects of planning and design on the Olmsted Brothers’ designed campus since 2000. Outside of Duke, he writes and lectures on topics such as cities, campuses, the environment and cultural landscapes. He is a frequent contributor to Landscape Architecture Magazine and has written for other publications such as Places Journal, Chronicle of Higher Education, and College Planning and Management, along with a regular blog post for the urban design website Planetizen. In 2011, Mark was awarded the Bradford Williams Medal, for recognition of excellence in writing about landscape. Contact him at Twitter: @mharrisonhough.

This article first appeared in Planetizen. All images via ASLA Awards, lead image by Matthew Moffit, PSU.