Michelle Biggs interviews architectural photographer Patrick Bingham-Hall , gaining insight into the creative process behind his photography. Landscape and architectural photographers play a key role in the field of landscape architecture. In the digital age, perhaps this is true now more than ever. Photographs are valuable tools for designers to effectively communicate and share past projects, and good photos of a completed design can be a powerful way to promote our work. Additionally, thanks to digitization, photography has also become increasingly accessible as a creative medium in the past 25 years. Today, more and more students and professionals in landscape architecture and design are turning to photography as a way to diversify their portfolios and better communicate their work. Patrick Bingham-Hall is an internationally recognized architectural photographer and writer, who as the owner and editor at Pesaro Publishing, has published a number of books on the topic of architecture and design. Today, he speaks to Landscape Architects Network about his work, and about how beginning photographers can improve their skills.

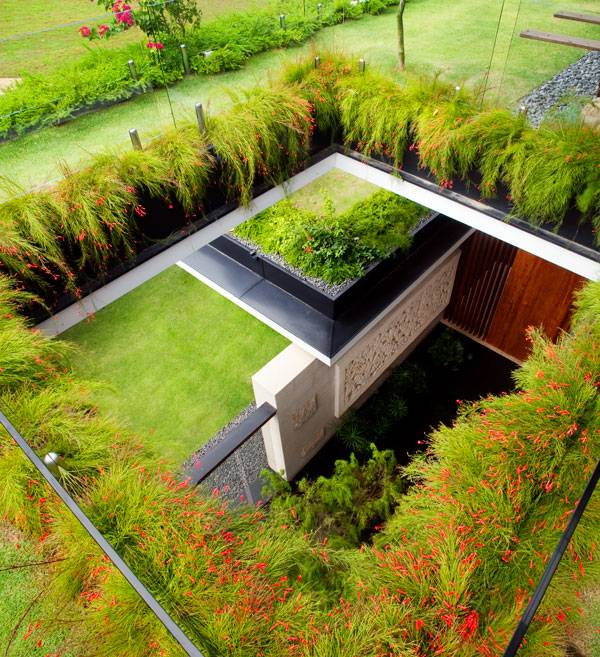

Meera House. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Interview With Patrick Bingham-Hall

LAN: First, thanks so much for taking the time to talk with us at Landscape Architects Network. Let’s jump right in. Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and the kind of work you do? PBH: First and foremost, I have always been a photographer. I didn’t have a clue what to do when I left high school in 1975, so I went to university and vaguely studied philosophy for a year or so. But I gave up when it became apparent that I was good enough at photography to make real money and get a ‘real’ life. So by the age of eighteen, I was a self-taught photographer with a reasonably lucrative business. I honed my photographic skills for the next fifteen years, and I also taught myself all that I could about the world of architecture, art, landscape, design, and the history of civilization. I did that through constant travel, and I conscientiously avoided formal tertiary education, in order to keep an open mind and to ensure that my photography did not lose its intuitive spark. By the mid-1990s, I felt obliged to broaden my scope by publishing books, and by writing as well as photographing. I had hit an intellectual ‘glass ceiling’ with photography. I had too many ideas and observations that needed further explanation. So I started up a publishing company, which did far better than I expected, and inevitably I began writing more and more of the text for the books. I had seen so much – in a variety of countries, cultures, and environmental contexts –that I had become a mini-encyclopedia. My writing just flowed out, and it worked very well in combination with my photos. Most of my recent books have been on architecture, landscape, and design in Asia, which has been fascinating because Asian cities and society have been changing so quickly.

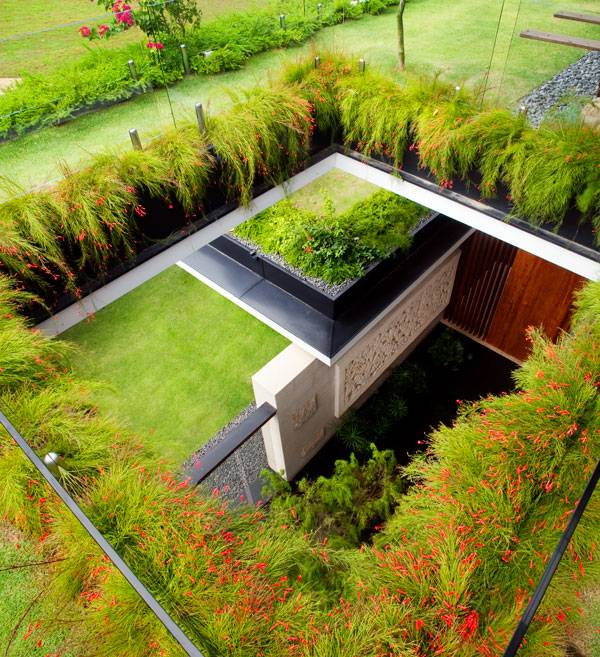

Cluny House. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

In your early years of photography, you spent time working in Australia’s underground music scene; what made you decide to shift your focus to architectural photography?

PBH: It was the mid-1970s… rock and roll ruled. So as a teenager, I didn’t really think about much else. But it quickly became very limiting at a creative level, as I wasn’t a musician. And, to be honest, by the late 1970s the music scene had lost its excitement. The great days of rock and roll were over. At a personal level, architecture suited me; because, I guess, I’m one of those dreamy people who like to look at things over a period of time… landscape, weather, artifacts. Nobody was going to pay me for photographing the landscape or the weather, but photographing buildings (architecture) was genuinely profitable. So I could make good money from doing the only thing I’d ever been good at, which was standing around looking at things. My parents had despaired of me, but I showed them!

Bamboo Garden Nanjing. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

What kind of tools and equipment do you use on a daily basis in your work?

PBH: I’ve never been obsessed by camera equipment. I know enough about cameras to get the quality required, but I do not want to be distracted by technicalities, and I prefer convenience and spontaneity to needless precision. I find it very frustrating to work with cumbersome or fragile equipment. Until the digital revolution, I used 35mm cameras for spontaneous shots and 5×4 inch plate cameras for formal commissions. The plate cameras were hilariously difficult to use, but the quality was remarkable. Because the film and processing was so expensive for all formats, I had to make sure that every photo was perfect. I still have this no-waste mentality… every shot must be terrific.

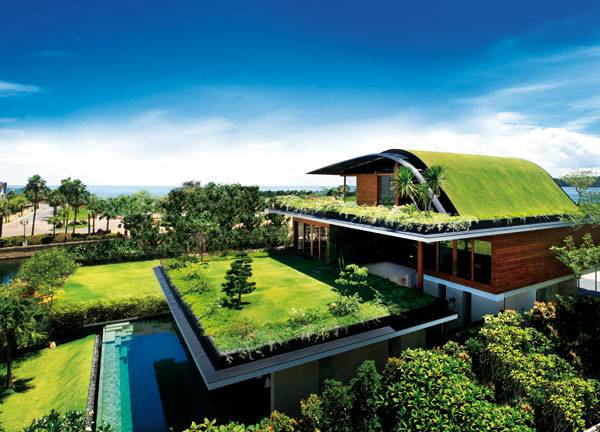

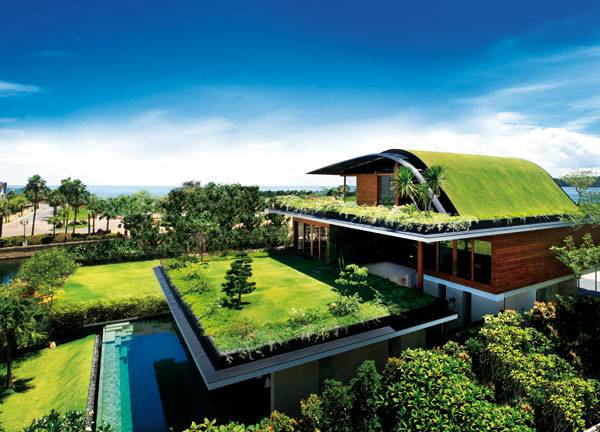

ParkRoyal on Pickering. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Pre-digital, I used a Nikon 35mm and a Cambo 5×4 plate camera, each with a set of three lenses; wide-angle, medium range, and telephoto. I kept to those constraints, and concentrated on the composition rather than experimenting with optical distortion. These days, I only have a Canon EOS 5D (the same shape and size as pre-digital 35mm) with a wide-angle perspective correction lens and a telephoto zoom. I think that larger format equipment is now superfluous, because the quality is so high when I put the images through Photoshop. It has been such a turn-around. It’s fantastic. I wish it had happened forty years ago. I must stress that a tall, rock-solid tripod is imperative. Nothing has changed there. I hate blurred images, and I need to use long shutter speeds because controlling the depth of field (range of sharp focus) by using a small aperture is essential for architecture and landscape.

Bamboo Garden Nanjing. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Can you describe your process when working on a photography project? Has the paradigm shift from film to digital photography changed this?

PBH: As most of my photography is outdoors, the process is entirely weather-dependent. So I either have to spring into action immediately, or hang around and wait and plan. Quite often, I have to make the best of a lousy situation, because of deadlines and schedules. I must confess that some of my best shots have resulted from lateral thinking when the weather has been dire. My basic plan of action is a speedy reconnaissance on the site, whilst bearing my client’s preferences in mind. I usually have a printed site plan, and if not, I sketch one. I cover the plan with little arrows and with notes as to the best time of day for certain views. I always look out for the unexpected. And I hate it when the architect or designer accompanies me… I can’t think freely, and continually discussing photos gets me nowhere. I’ve never used an assistant, unless they can keep their mouths shut! The switch to digital has had one amazing advantage… the amount of photographs that can be taken. I can now take forty in a day, whereas fifteen used to be the practical limit. Of course, this has a downside, as one day’s photography means two days worth of Photoshop on the computer screen. I do all my own Photoshop (digital imaging), and I do that the way I used to work in the darkroom. It’s all about achieving a harmony of light and shade, and adjusting the colour balance. Unless absolutely necessary, I refrain from manipulating the image with layers of backgrounds, and adding psychedelic skies. You can always tell when that’s been done, like you can always tell when HDR (High Dynamic Range) has been used.

Meera House. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Where do you get your inspiration from? Are there any books or websites you can recommend as resources for inspiration?

PBH: To be honest, my only tangible inspiration has come from earlier photographers and artists, who rarely photographed or painted architecture, although they all depicted landscape. I loved photographers such as Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Brassai, Kertesz, Dorothea Lange and Harry Callahan. But my most direct influence came from gazing at paintings, particularly the landscape settings of the Renaissance, Chinese scrolls, and the Pictorialism of the late 19th century. I hate to say this, but I have never really paid much attention to professional architectural and landscape photography. I look at the content, rather than the photographic style. So I don’t have any recommendations for contemporary books or websites. I would advise studying the architecture and the landscape (the subject matter) before getting too caught up in the photographic possibilities.

Cluny House. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Many of our readers are interested in developing their skills in photography so that they can better communicate their work. What advice would you give to any beginning photographers?

PBH: The most important thing is to document and to correctly interpret the design or the architecture. The photograph means nothing if you can’t decipher the subject matter or the designer’s intention. Obviously, the most desirable outcome is a stunning photo that also shows the architecture and landscape in its best light. Patience is crucial… you need to wait for the critical moment, and that can take hours, maybe days. So many things conspire to spoil a photograph, such as unfavourable weather, the wrong people in the wrong position, shoddy construction or maintenance, etc. A photographer must be philosophical, whilst preparing for that brief period when everything falls into place.

Alila Villas Uluwatu. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

On the other hand, what are some of the biggest and most common mistakes you see students and amateur photographers making in their work?

PBH: It took me fifteen years before I thought that I was good enough! I guess that most people don’t want to wait that long, so here are a few basic tips… Correct perspective is essential. That means buildings, and objects, and trees, should rise in a perpendicular manner, at 90 degrees from the ground plane (unless they’re designed otherwise). When we view the landscape, we automatically factor in the perspective correction, but cameras do not. So unless you fix the perspective, everything falls over backwards. Utilize the angle of the sun effectively, whether it’s back-lighting, side-lighting, front-lighting, or no sun at all. I automatically prefer a diagonal (45 degree) sun angle, both vertically and horizontally, because that best displays the volumes, the spaces, the textures and the components. Learn the fundamental laws of photography and camera use. Nothing has changed, despite the digital revolution. In order to know what you’re doing, you need to understand shutter speed, aperture width, depth of field, correct exposure, ISO rating, and lens distortion. It only takes a day to figure that out, and there is little else that you need to know in a technical sense. The rest is just trial and error.

Alila Villas Uluwatu. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

What do you think are some of the benefits of learning photography for designers like landscape architects?

PBH: I’m not sure that there are any real benefits, apart from research and reference. I have met very few architects, landscape architects, and interior designers who take good photos; which is possibly an interesting topic in itself. Maybe they’re too close to the subject, whether it’s their own work or somebody else’s. Whenever I look at a designer’s photos of their own work, I quietly chuckle about how they got it wrong! They only see what they want to see, which is what was in their heads, not the real world.

Forest Walk. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Forest Walk. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Finally, would you mind sharing with us one of your favourite shots or a favourite project you’ve worked on? In terms of LAN and this discussion, possibly the most rewarding projects were two collaborations between an architectural practice and a firm of landscape architects.

WOHA Architects and

Cicada Landscape Architects worked together on two resorts:

Alila Villas Uluwatu in Bali, and the

Sanya InterContinental on the island of Hainan in China. The landscape and the architecture blended seamlessly, so it was impossible to say ‘

this is architecture and this is landscape’. I think I referred to both projects as

‘archi-scape’ in books that featured the resorts. I was lucky enough to be commissioned separately by WOHA and Cicada for each project, but both firms used all of the photographs. When I took the photos at Bali and Sanya, I realized that I was not specifically trying to show off either the architecture or the landscape. The formal geometries and the contextual integration were consistent across both sites, as the forms of the buildings extended into the gardens, and vice versa. Ecological awareness and rehabilitation were central to the planning of both sites, which I found particularly pleasurable in a resort environment, where human comfort is usually prioritized at expense of the natural landscape and habitat.

Intercontinental Sanya. Photo credit: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Thank you again for taking the time to discuss your work with us here at

Landscape Architects Network. To learn more about Patrick Bingham-Hall’s work, you can visit his

website or check out any of his stunningly illustrated books.

Recommended Books Featuring Work from Patrick Bingham-Hall :

Interview by Michelle Biggs

Published in Blog