Biomimicry or biomimetics refers to the direct study of nature, its organisms, ecosystems, and processes to inspire solutions to anthropogenic problems. It is based on the Darwinian principle of evolution through natural selection -the basic premise that species survive because they are well adapted to their environment. Traditionally, when researching for a product, designers will look at what products have gone before. Building on the successes of the previous models, designers then add new innovations to hopefully make a better product. This is commonly known as research and development or ‘R&D’ for short. In biomimetics designers look to how nature has solved problems. This is then studied and copied. This method of copying nature takes full advantage of the 3.5 billion years of ‘R&D’ that nature has undergone, through natural selection.

Seed from which Velcro was created. Credit: Kalyan Varma, under GDFL

Perhaps the best known example of biomimicry is Velcro. That well known staple of kindergarten shoes was originally developed by Swiss engineer George de Mestral in 1941. Whenever Mestral returned from his walk he would always have to brush the burs of seed heads from his dog’s fur.

He wondered how it was that the seed heads came to be so entangled in his dog’s fur. When he studied the burs on the seed heads he noticed how they had tiny hooks on them. The many burs acted together to ‘grip’ onto the fur of the dog. Thus he designed a product which had tiny hooks on one side, and loops on the other.

Biomimetics can be a very smelly idea! Biomimetics is much older than the 20

th century though. Arguably the earliest and simplest form of biomimicry would be the use of dung when hunting. Early hunters noticed that if they disguised their smell with the dung / faeces of their prey, then they were able to get much closer without frightening them away.

Another example is human flight. The ability to fly, using planes and gliders, is directly linked to our early inspiration drawn from birds. We copied the wings and the aerodynamic shapes of birds until eventually in 1903 the Wright brothers took the

first manned flight.

Marine birds fly at Cape Hay in the High Arctic. Credit: Hans Hillewaert, 2CC BY-SA

Famous first flight of the Wright Brothers. Credit: Public Domain via britannica.com

To understand biomimetics it is important to make the clear distinction between domestication and biomimicry. Domestication is where humans use an organism directly to solve an anthropogenic problem. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is farming. We simply grow the plan / animal / fungi and then eat it. A more sophisticated example of domestication is phytoremediation.

Examples of phytoremediation can be seen in the following articles: Developing on Inner City Brownfield Sites Top 10 Reused Industrial Landscapes

Phytoremediation: Shanghai Houtan Park, Turenscape

In the example above humans use an organism or natural process directly to achieve their aims. The plants used in phytoremediation are simply domesticated in exactly the same as wheat in a field. Biomimicry, however, differs in that designers look to see what it is that the organism is doing, how they are doing it, and then sees if it can be replicated in a cost effective and performance enhancing way.

Unveiling of LZR Racer in NYC 2008-02-13. Credit: Public Domain by Kathy Barnstorff

In 2008 Michael Phelps received much well-deserved attention as he won eight gold medals at the Beijing Olympics. But during the Beijing Olympics the swimsuits of some of the top athletes received as much attention as the athletes themselves. Sharkskin suits had been around for a while, but their unprecedented success from 2000 to 2008 won them notoriety. Speedo had developed an all body swimsuit which took inspiration from the skin of sharks. Sharks’ skin is covered in dermal denticles, or ‘skin teeth’. These tiny scales have grooves running along their length in line with the direction of water flow, thus breaking the water tension and minimising turbulence. Speedo’s ‘Fastskin’ swimsuit is also covered in tiny artificial dermal denticles. This gives the athlete an advantage as they are more hydrodynamic.

Biomimicry in Landscape Architecture

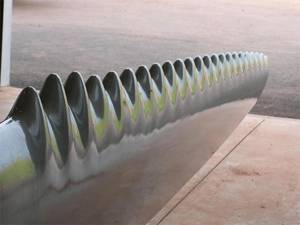

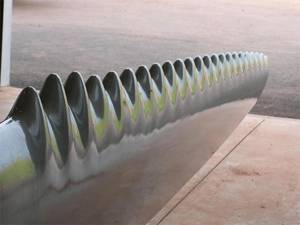

Whalepower fin. Credit: Licensed under CC

Another aquatic example of biomimicry, which is more closely aligned with Landscape Architecture, is the wind turbine blade developed by

Whalepower. The turbine blade is based on research carried out by Duke University, West Chester University, and the US Naval Academy. In this research scientists studied the bumps on the fins of whales, and concluded (perhaps counter-intuitively) that these bumps help reduce drag by 32% and increase lift by 8%! Today many landscape architects are engaged in planning battles over the landscape and visual impact of wind farms. One of the main considerations of wind turbines is the noise they make. The turbine blades developed by Whalepower are similar in shape to whale flippers and help to increase efficiency whilst reducing noise.

Wind Turbines an eyesore or a brilliant host for bioremediation. Credit: Angaurits, CC 3.0

So much of the inspiration behind biomimetics comes from the sea. This is perhaps not surprising as 70% of the earth’s surface is water, and it is estimated that the majority of the earth’s biomass lives in its oceans. Furthermore it is a commonly held belief that life began in oceans, and so there has been a longer time for evolution’s ‘R&D’ to develop advanced solutions to problems.

The Future of Biomimetics The future of biomimetics is set to revolutionise urban design as Janine Benyus, author of

Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, turns her attention to introducing biomimetics to town planning, together with architectural firm

HOK. The basic principle is that if Town Planners, Urban Designers, Landscape Architects and Architects can design cities to be more like functioning ecosystems then we can design out problems of water attenuation, air pollution, and carbon retention.

Do You See A Road Network? A River System? A Circulatory System? Or Just A Leaf? Credit: Christoph Rupprecht; Leaf Structure VII, CC 2.0

Whilst still in its early stages, the joint venture hopes to both create new cities which thrive, and retrofit failing cities with biomimetic infrastructure. Many of the ‘tools’ for this will be familiar to fans of Landscape Architecture; greenways, undeveloped flood plains, green walls / roofs, permeable paving, etc. But the key is to use all these tools to create a city which behaves like an ecosystem. Projects are already under way in China and India.

From the microscopic scale of dermal denticles to the macroscopic scale of city planning, biomimicry and biomimetics can offer a wealth of design inspiration to product, architectural, and landscape design. It would seem the possibilities are as endless as life is diverse. Recommended reading: Biomimicry: Inventions Inspired by Nature by Dora Lee The Shark’s Paintbrush: Biomimicry and How Nature is Inspiring Innovation by Jay Harman Article written by Ashley Penn Return to Homepage

This article was originally submitted to Landscape Architects Network

Published in Blog