Article by Paul McAtomney We take a look at 5 things that happen when you become a landscape architect. Despite its increasing scope and relevance in 21st-century society, landscape architecture continues to act as a largely unseen profession. It attracts an assemblage of people to its learning; more often than not, individuals coming from diverse backgrounds, later in life. Having recently completed my undergraduate studies as one of those individuals from a diverse background, commencing work in practice, and ruminating on my experiences thus far, I realise I lacked a sound grasp of the physicality of the world as an unversed student. This is not to suggest I am now versed; far from it, in fact. However, there are numerous things I find I do in interpreting and responding to the natural and built environment on a daily basis now as a practicing landscape architect that as a student I was not so attuned to, and to the non-landscape architect might sound quite bizarre. The following commentary, I hope, will encourage people considering entering the profession, be comically recognisable to other landscape architects, or simply give interested readers a sense of how landscape architects interpret the world around them. 1. You Eat the World with Your Eyes Wandering through the urban fabric becomes an entirely different, sensual, experience, and one that offers a plethora of insight if you are willing to look and observe. The transition from student work (speculative and often large-scale) to real-world, built work provides a pleasant jolt, and quickly you find yourself becoming highly attuned to how the physical environment is put together, layer by layer, piece by piece—be it a detail of how two materials coalesce, a type of paver, a concrete finish—for example—Beekman Plazas by James Corner Field Operations (Figure 1). These and many others are the things that I feast on daily now, having had no such level of attentiveness as a student. Looking at the built environment also entails a critical sense of thinking about the raw materials wrought from the earth and where they come from—the origins of the gravel, concrete, steel, and timber that comprise the built environment. As we continue to witness the complete urbanisation of society, the general populace is in large part spatially removed from the landscapes that are exploited to yield such materials.

Figure 1: Beekman Plazas paving detail. Image credit: James Corner Field Operations.

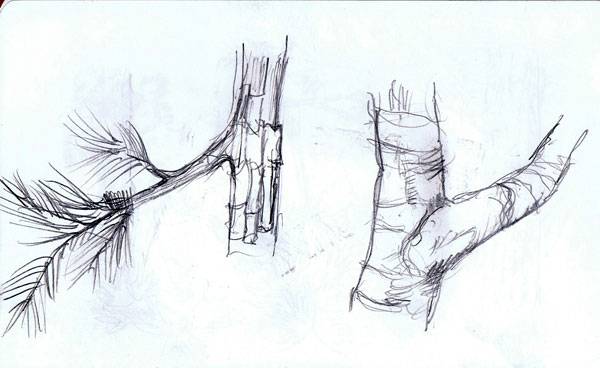

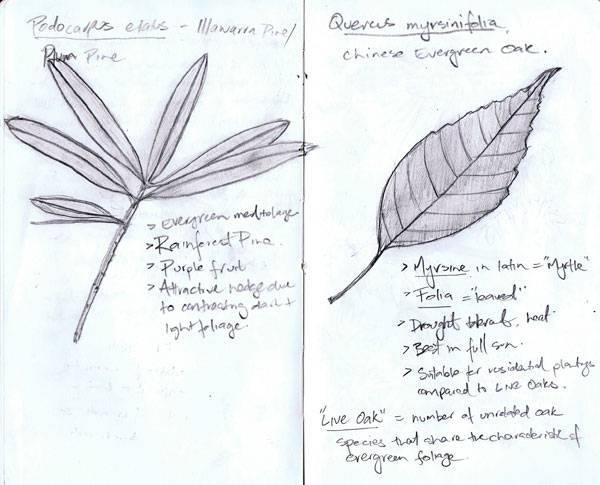

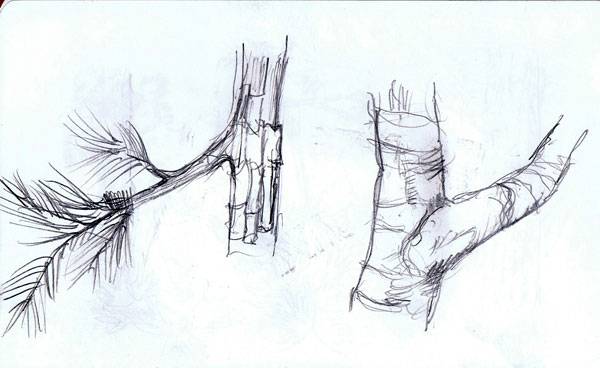

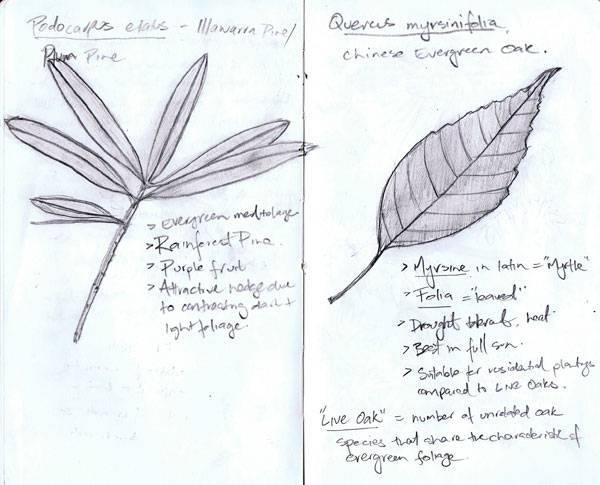

In university, course material on plant matter is pretty light. Through my four-year degree, I had one subject on plants, and it was heavily horticulturally-based. Rather than exhibiting a mastery of horticulture, I believe it is much more important to learn about plants endemic to your local area and how they can be applied through the lens of experience, the life cycle of plants, and the ecological function that they provide. You will rapidly discover that to gain plant knowledge, it is essentially up to you. To do so, I generally photograph any interesting groundcover, shrub, or tree that catches my eye and either attempt to use a plant finder website, ask someone at work, or simply search for local government data on plants in a particular suburb and begin a process of subtraction until I can make an identification. Doing so the latter way seems to ingrain the species into my mind as it involves more research, as does sketching the plant in question into your sketchbook, labelling it, and describing it. (Figures 2 and 3).

Bark and trunk texture explorations. Image credit: Paul McAtomney

If you think you’re not versed in verdure as much as you’d like to be, be sure to check out all

10 of the 10 Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them.

Leaf explorations identifying new species. Image credit: Paul McAtomney

Figure 3: Leaf explorations identifying new species. Image: author’s own.

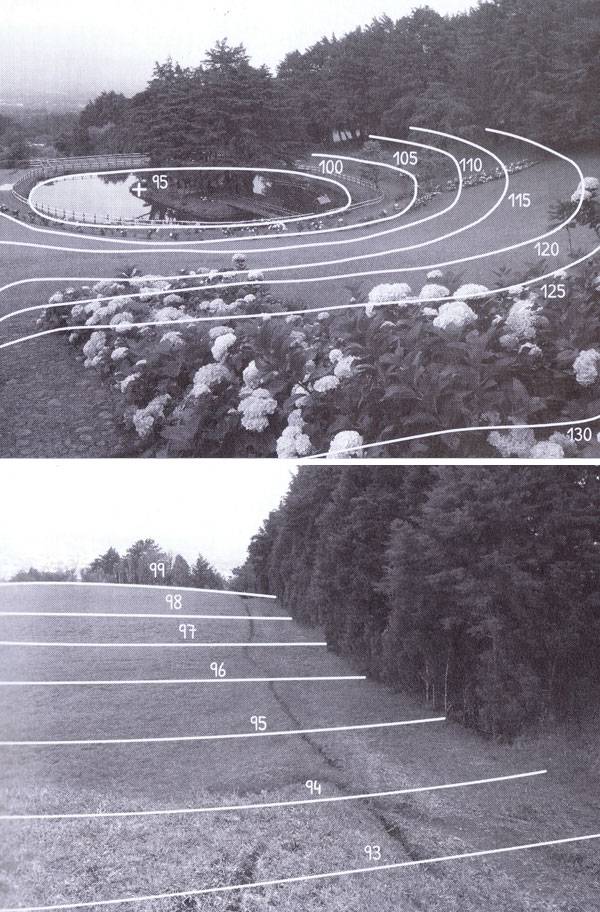

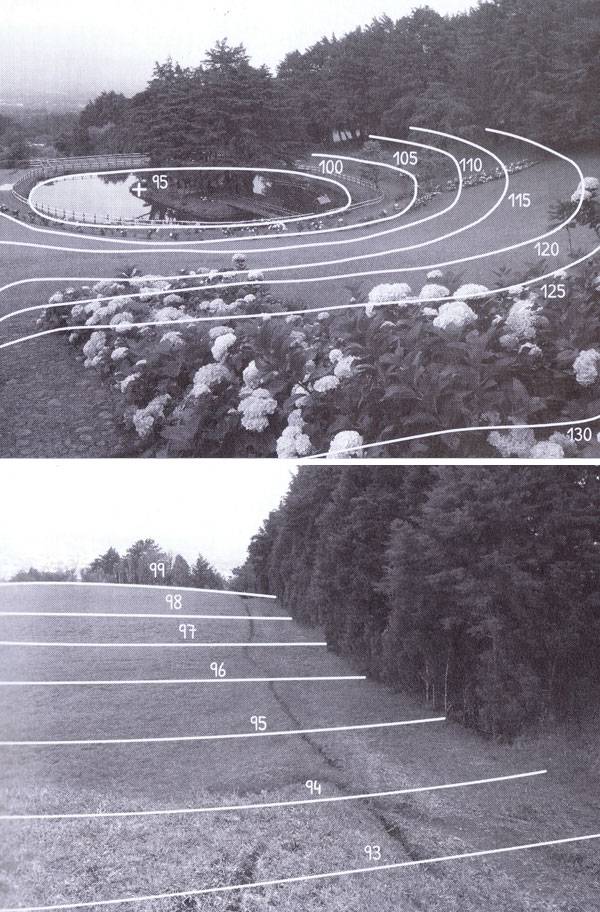

3. You Survey the Land I look at hills, valleys, and slopes, and see contours. This is a great way to learn to read the landscape through natural and cultural visual clues, and a perfect example of the critical interpretation of the land that happens in the mind of a landscape architect. Perusing the built and natural world by foot, I try to sense and estimate the gradient of a given slope, and also visualise drainage patterns in the landscape (Figures 4 and 5).

Figures 4(top) and 5 (bottom): How to read the landscape around you. Image credit: Paul McAtomney

As the bread and butter of landscape architectural practice, being dextrous at grading and drainage is an essential skill to develop. Having the ability to visualise landforms and contours is aided a great deal by books such as

Landscape Site Grading Principles: Grading With Design in Mind (Figure 6).

4. You People-Watch More than Ever People watching is a thoroughly splendid way to pass the time in public space. Of course, not only landscape architects do this, as the general populace also gravitate toward idly observing the urban spectacle of public life. However, as landscape architects, we are attuned to picking up individual or collective idiosyncrasies, as it is an inherent part of analysing space and the way people appropriate, activate, abandon, or territorialise space. Take

New Road by Landscape Projects and Gehl Architects, for example (Figure 6). Jan Gehl is a huge advocate of urban quality and walkability, and describes how in spaces such as this, the edges hold a magnetic attraction for people known as the “edge effect”; perfect for people watching and a trait the

Top 10 Public Squares of the World no doubt possess.

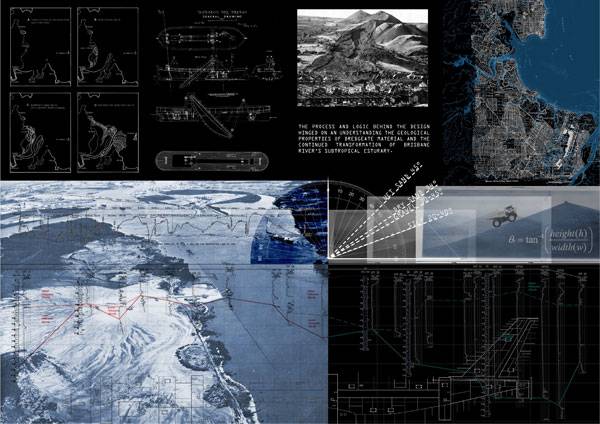

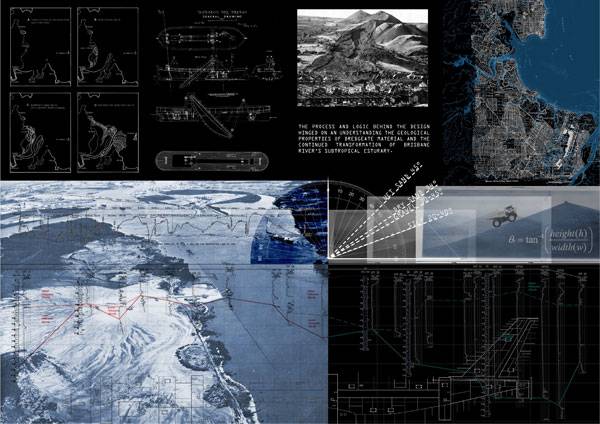

Figure 6: New Road, Brighton, design by Gehl Architects. Image: Gehl Architects

Rarely is a site ever a blank slate, a tabula rasa. No landscape is void of historical traces and layers. Thinking critically about places and how they have come to fruition—developing an understanding of the observable conditions of the past and present—is a part of the landscape architect’s deftness in making educated guesses about future trajectories and interactions at a systemic level (Figure 7). As an individual, I have found that you develop your very own “

language of landscape”, as

Anne Whiston Spirn so eloquently put it, in your own unique fashion and at your own pace, with no determinant modus operandi. Here, curiosity is key.

Figure 7: Observing site conditions past and present. Image credit: Paul McAtomney

Landscape architects’ generalist tendencies are often considered our major downfall; to the contrary, I believe they are our greatest means of agency as our remit continues to broaden in scope. These are five of the most noted changes in the way I personally see and experience the world around me as a landscape architect, and truly believe it’s a very special way of seeing and knowing.

If you are a fellow landscape architect reader, please comment and add to this list! Go to comments Recommended Reading:

Article by Paul McAtomney

Published in Blog