Let me introduce to you, Bano, a frail looking, dark skinned 39 year old woman who has not been educated beyond grade five. She migrated from her village and came to Delhi, India, where she became a sex worker and now lives in G.B. Road, continuing in the same profession. Bano doesn’t regret the decision she made then, but she is keen to explore alternative opportunities. She doesn’t have the skills or resources to do so.

Recognizing the Landscape of Sex Work in India is a project that focuses on a design strategy to uplift the social living conditions of the people living in red-light districts.

The sex industry has always been a part of cities and is said to be the oldest profession in the world, however, the urban areas that cater for sex work are often considered illegitimate parts of the city. In countries like India, the stigma associated with this profession is prolific. The negative effects of stigmatization not only extend to the lives of the people associated with the sex industry but also affect the place they occupy.

With approximately 40 million sex workers in the world, in India, there are around 660,000. Statistics show that the population of sex workers has risen by 50% in less than a decade and 73% of them live in the metropolitan cities of India like Mumbai, Delhi and Kolkata. As the number of sex workers increase in an area, the community of women like Bano negotiates with marginalization which can result in being delineated from the city to lead a socially degenerated life.

Image: Michelle Thomas Zacharias

G.B. Road has 77 brothels and 4000 sex workers, or Didis (a term used to address women with respect). It is known to be one of the largest commercial markets for hardware and machinery shops in Delhi and caters to a lot of visitors during the day. In a packed row of buildings along this road, the shops occupy the lower levels and the brothels occupy the second and the third levels. There is also the presence of an NGO organization that was formed in 2012 as a response to the existence of the red light district.

Challenging gentrification, the methodology generally used to treat marginalized areas in urban design, it is observed that there is a positive system that exists within such areas and landscape architecture has the opportunity to tap into it.

A landscape architect has the potential to produce an area that acts as a platform to enhance the social activities that are being conducted by community groups and other organizations and to act as a facilitator of social innovation in the distribution of design skills and thinking which will help create a wider platform for activities and engagement.

In the Theory of Urban Weave, Jeremy Till explains that the warp of the weave is the city fabric as it exists and the weft is the small catalytic act that negotiates, adapts and runs through it to positively impact it and harnessing community energy in positive ways to empower them.

The concept of inducing catalytic urban weave actions is relatively new in the Indian context. However, most activities that occur in the public spaces in the Indian context are organic and impromptu which are adapting and negotiating in nature.

The two precedents which were studied to understand how vulnerable areas like the Red Light Districts have been dealt with in terms of Urban Design are Skipper’s Quarter, the Red Light District of Antwerp and Khayelitsha in Cape Town. These precedents formulated design strategies and principles based on the Theory of Urban Weave. The use of tools like community engagement, urban acupuncture and mapping not only resulted in the upliftment of the place but also the community.

Image: Michelle Thomas Zacharias

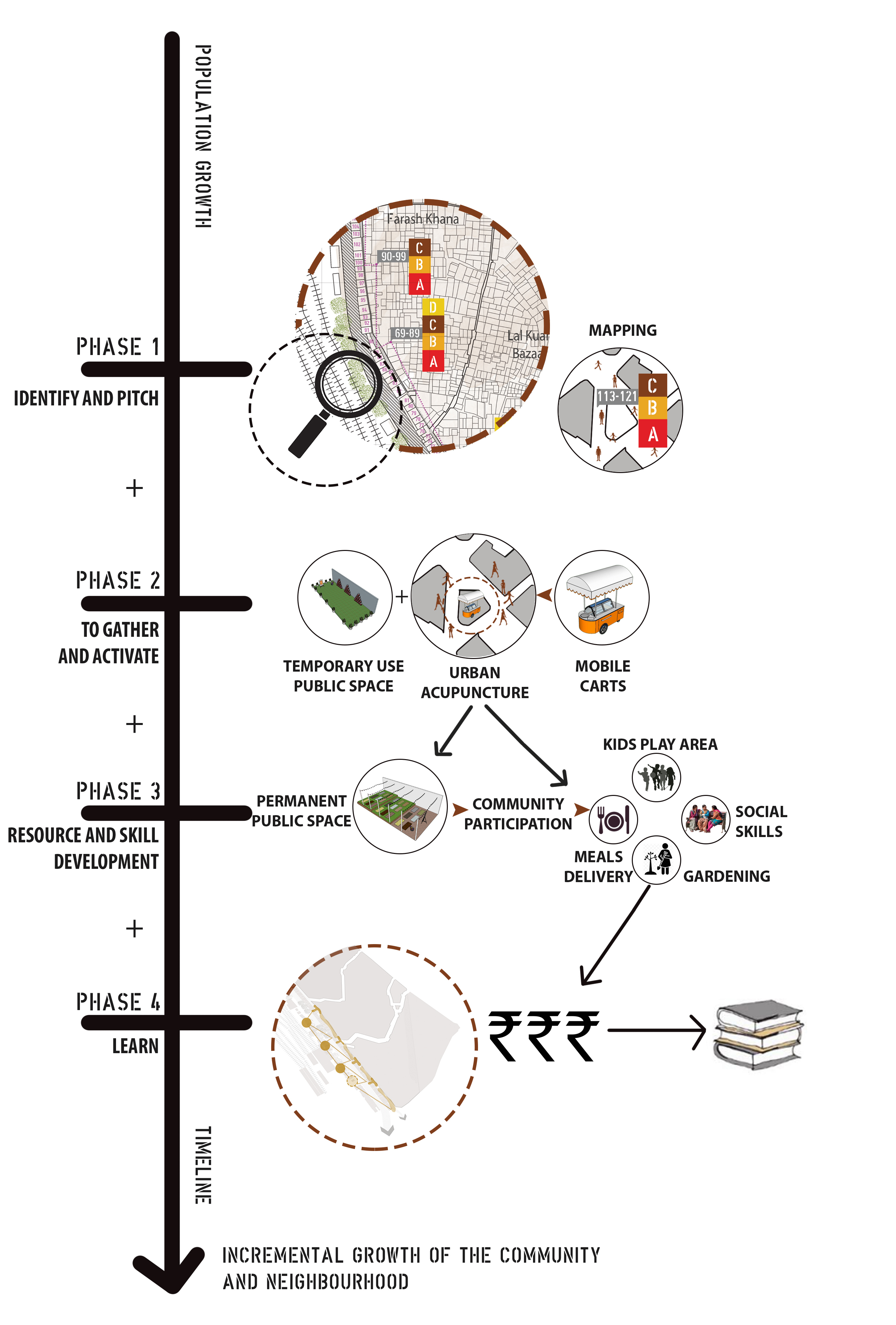

This project is envisioned as design strategy in four phases where convivial tools like mapping, urban acupuncture and community engagement are implemented to achieve a responsive design outcome.

Phase one is to identify, mark and provide a distinctive identity to the sex workers in terms of addresses through mapping. Here the role of the landscape architect would be to provide the spatial understanding, drawing and power of mapping to the NGO.

Phase two is about enabling strong community bonds for the Didis. Two actions of urban acupuncture are proposed here, the introduction of mobile carts and temporary activity space for the NGO. This would assist in assisting Didis coming out and interacting with these interventions more often and forming new relations within their own community.

Phase three is about making these points more permanent in nature and assisting in making them multiply in order to become platforms for the existing NGO activities that work on building social skills for the Didis.

By Phase 4, an additional user layer of activity is expected to evolve through Didis involvement in social activities on site. All these spatial interventions create a network where the Didis can feel a sense of belonging, community, safety, ownership and identity.

As these spaces allow a financial inflow into the community, this revenue could be invested into attaining higher social needs of the community. This revenue generated could be invested into building learning centers and introducing mobile libraries, amongst other things, on the site and within the community.

It is not about discouraging the Didis from what they do to earn a living, it is about providing them with means and resources through design and collaboration that open up choices and opportunity for them that can help uplift and improve their social living conditions. The tools of urban weave enable the community with that freedom of choice, which in itself is a way of empowerment.

Through further study, research, and analysis, this approach could be continued not only in red-light districts but also other marginalized and stigmatized areas where the community can be empowered through design to alter the landscapes. Ultimately, people of a place make the place what it is.

—

Michelle Thomas Zacharias is the winner of the Hassell Travelling Scholarship – Robin Edmond Award. Now in its 30th year, the award recognises graduating landscape architecture students who show outstanding potential for future contribution to the profession. The award provides the winner with the opportunity to expand their education through travel to a destination undergoing significant development or renewal.

Lead Image: Michelle Thomas Zacharias

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured