Author: G. Ryan Smith

Book Review: Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs

Most landscape architects are likely already familiar with horticultural reference book author Michael Dirr, a professor of horticulture at the University of Georgia and author of the seminal Manual of Woody Landscape Plants. In many ways, that book is the gold standard for a plant reference book and many landscape architects likely already have a copy on their bookshelves. So, if that’s the case, is a copy of Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs (2011; Timber Press; 952 pp.; $79.95) truly necessary or simply redundant?

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs by Michael Dirr, p. 34. Source: Timber Press.

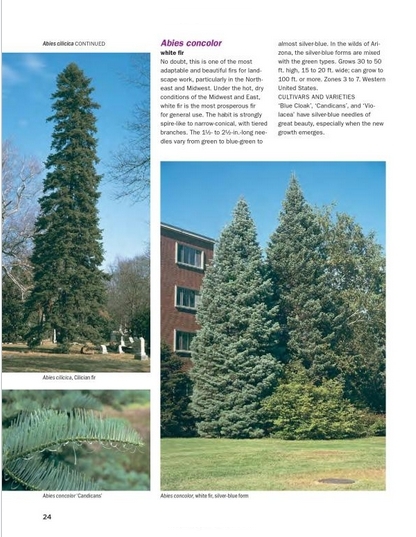

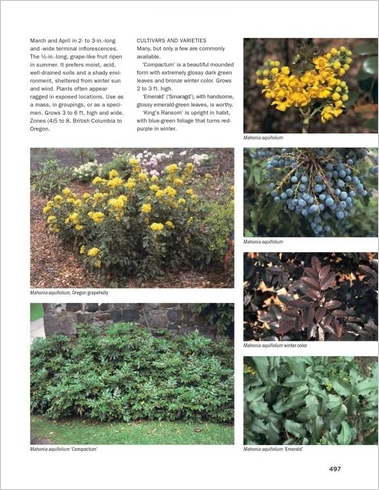

The answer, of course, will depend on the individual. But while Encyclopedia covers the same general topic as Manual, its purpose and format are different. The first thing that the reader will notice is what a handsome volume it is; whereas Manual focused on plant identification with line drawn illustrations of foliage, fruit, and bark, Encyclopedia is lushly illustrated with full-color photographs, often of the whole plant or groups of plants as opposed to close-up shots of identification details.

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs by Michael Dirr, p. 24. Source: Timber Press.

The ubiquitous presence of full-color photos should tip the reader off as to what the purpose of Encyclopedia is as compared to Manual. It’s more of a guide to plant selection than a strictly scientific reference book. While the book is organized in a similar fashion – alphabetically by genera with entries for specific species – the entries themselves are slightly different. While each entry includes often abbreviated scientific information, they’re largely written in a more informal and avuncular style than was Manual. The focus here is less on rotely going through a set of scientific criteria for each plant as it is on providing basic scientific information along with practical and sometimes personal commentary on the plant, its propogation and use, and even suggestion for aesthetic decisions in terms of planting.

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs by Michael Dirr, p. 497. Source: Timber Press.

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs by Michael Dirr, p. 497. Source: Timber Press.

While the number of genera it contains is 380, the total number of species and overall amount of information here is less than was in Manual. However, it contains more informal advice on plant selection and propogation, gleaned from Dirr’s decades of experience which might prove to be invaluable. Moreover, the inclusion of the photographs and the more readable text make the book a pleasure to be hold, meaning that you are more likely to pull the book and flip through it for the fun of it as opposed to only pulling it off the shelf when you have something specific to look up.

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs by Michael Dirr, p. 511. Source: Timber Press.

As such, it’s something of a bridge between the hobbyist and the professional. While it’s no doubt professionals will enjoy the information and find much of it useful, its presentation and format are such that it will appeal to serious hobbyists as well. With the lush packaging and abundance of attractive photography, it’s also the kind of coffee table book that professionals might leave on a table for clients to flip through. Appendices also include tables for plant selection for specific characteristics such as flower color, salt tolerance, and habit shape, making Encyclopedia both a useful and enjoyable horticultural reference book.

Let us know what you think!

Have you read this book? What’s your opinion?

What’s your favorite horticultural reference book?

What websites or applications do you use as horticultural references?

Five Modernist Landscape Architects

Modernism as a whole had a major impact on the twentieth century, especially in the arts and in design. Architecture, landscape architecture, film, movies, and art were all heavily influenced by the movement. While modernism’s impact may have been less significant in landscape architecture than in other disciplines – landscape materials, for example, didn’t change as radically in the twentieth century as did building materials in architecture – there were nonetheless many academics and practitioners who sought to move the profession forward as modernism came to prominence in the early- and mid-20th century. Below are five modernist landscape architects whose work you should be familiar with:

1. Lawrence Halprin (1916-2009)

If Lawrence Halprin had only built one project and that project was the Ira Keller Fountain in Portland, Oregon, he would still be one of the all-time greats of landscape architecture. The park, built in 1970, features fountains that are abstract representations of natural waterfalls. The most remarkable element of the park for its users, however, is its lack of boundaries. It’s designed not to restrict users’ movement but to encourage open engagement with the park’s elements, enabling people to interact with the water features rather than to “keep out.” Fortunately, though, this wasn’t his only project, with some of his other highlights being a redesign of Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco, Freeway Park in Seattle, and the FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Image: Halprin’s Keller Fountain in Portland. Photo by Phil Gilston via Dataisnature

2. Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994)

Something of a remarkable anomaly in the field, the Brazilian landscape designer changed many landscape architects’ preconception of what their profession might entail. Unusual for a designer, he is known as much for his design process as for his results, creating living landscapes out of designs he worked out on canvas paintings. A prolific designer and superb plantsman, Marx left a legacy of landscape design in his home country and abroad in works ranging from some of the landscape areas of the modernist new Brazilian capitol of Brasilia to Ibirapuera Park in Sao Paolo and Biscayne Boulevard in Miami, Fla.

Image: Safra Bank Roof Garden, São Paulo. Photo by Jon Whittle, via Garden Design

3. Dan Kiley (1912-2004)

Dan Kiley was one of three landscape architects (along with James Rose and Garrett Eckbo) pushing for the incorporation of modernist ideas into the profession while at Harvard in the late 1930s. The less polemical of the three, he nonetheless made an impact early on in his career with a series of influential articles on the topic published in Architectural Record. While he left Harvard without graduating, he went on to a long career as a practitioner, completing hundreds of projects before his death in 2004. Modernist geometry weighed heavily in his designs, which made his work simultaneously up to date and connected to older landscape stylists.

Kiley’s South Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago in Chicago, Ill. Photo by Charles Birnbaum, courtesy of Cultural Landscape Foundation.

4. Garrett Eckbo (1910-2000)

One of the Harvard three that were pushing for modernism in landscape architecture in the late 1930s, Eckbo applied his modernist ideas to a variety of different contexts. One of the few landscape architects to genuinely seek to integrate social values into landscape design, he launched his career by attempting to fuse his modernist ideas with designs for migrant farmworker housing built by the Farm Security Administration in California. He later expressed that he had a “crisis of conscience” from producing residential designs for wealthy clients. He went on to be one of the cofounders of EDAW and worked on projects ranging from Mission Bay in San Diego and the Fresno Mall in Fresno, California. He was also a prolific writer, authoring a series of articles alongside Dan Kiley and James Rose while at Harvard and publishing four books.

Image: Eckbo’s Ambassador College in Pomona, Calif. Photo by Charles Birnbaum, courtesy of Cultural Landscape Foundation.

5. Thomas Church (1902-1978)

Perhaps the preeminent residential practitioner of modern American landscape architecture, the Boston-born Church is most known for his modern California garden style. His landscape designs harmoniously defined the laid back California modernist housing style in that state where individuated housing is so prominent. He also authored two books on the topic, Gardens are for People and Your Private World: A Study of Intimate Gardens.

Image Above: Church’s Parkmerced in San Francisco, Calif. Photo by Charles Birnbaum, courtesy of Cultural Landscape Foundation. Lead image (top): Thomas Church’s Donnell Garden in Sonoma, Calif. Photo by Charles Birnbaum, courtesy of the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Now, it’s your turn… Who is your favorite modernist and why?

Two books on Geodesign

In recent years, Esri, publishers of the ArcGIS suite of software, has been promoting a concept called geodesign in an attempt to meld the geographic disciplines withe the design disciplines. So far, the results have been mixed, at least in terms of how well it has caught on. While it has yielded a certain amount of attention in the design disciplines, many have held that geodesign is simply repackaging existing ideas and practices and is not offering anything new.

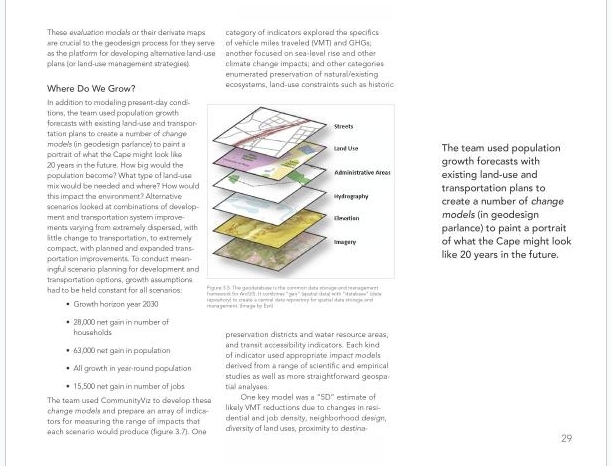

So is geodesign something new or is it simply old wine in a new bottle? The answer, according to two recent books published by Esri Press, is a little of both. Shannon McElvaney’s Geodesign is something of a “best practices” book that provides an overview of some recent/cutting edge projects in which Arc software has been used to achieve sustainable results in the built environment. The second, Carl Steinitz’s A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design provides an elaborate (possibly visionary) framework for how the process of design should best be conceived.

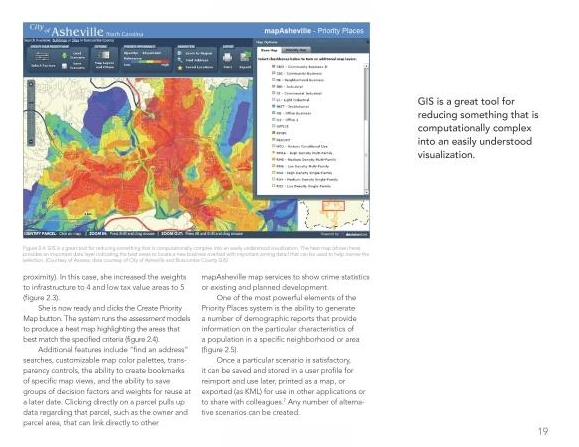

Mcelvaney’s text is the more concrete, easily defined and approachable of the two, in that it’s largely an illustration of a series of case studies of how GIS technology has been used to support sustainable design and development. An introductory chapter gives a general background and overview of the topic, in which McElvaney states that Geodesign is both nothing new and something different, in that changing geography by design has been happening for eons but that Geodesign is an update of that. The remaining chapters consist of case studies of sustainable approaches to design and how Esri’s technology is currently being used to advance the goals of sustainability.

Geodesign by Shannon McElvaney, p.29. Source: Esri Press.

Geodesign by Shannon McElvaney, p.29. Source: Esri Press.

Steinitz’s text is the more abstract and intellectually sophisticated of the two, in that it explicates the process of an approach towards collaborative design rather than focusing on the design themselves. In fact, calling it a text on Geodesign may be slightly misleading. It’s really a presentation of an approach to design that Steinitz, a professor emeritus at Harvard, has been teaching in the classroom for nearly 35 years entitled the landscape change model. In short, it is Steinitz’s long-extant landscape change model adapted for Esri’s Geodesign advocacy that has been influential to a generation of landscape architects and designers, including the development of Esri’s software suite.

A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design by Carl Steinitz, p. 45. Source: Esri Press.

What is confusing to many designers about Geodesign is that it does not necessarily make one a better designer in the sense of producing a more aesthetically pleasing site. What it does is highlight how GIS technology and its informational and analytical capacity can be used to inform and enhance design, whether that’s mitigating environmental impacts or collaborating with fellow design professionals. While both texts are informative, and both state that geodesign is both nothing new and something different – an up-to-date spin on ages-old building practices – neither really makes a strong argument as to why geodesign should necessarily be considered a distinct activity from previously existing sustainable design and building practices.

A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design by Carl Steinitz, p. 19. Source: Esri Press.

Geodesign or not, Steinitz’s text is invaluable in that it puts on paper an elaborate and influential design model that heretofore was only accessible to students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. McElvaney’s text is useful for being a set of best practices for how GIS technology is being incorporated into sustainable design efforts. Whether or not geodesign is worthy of its own distinction or is merely a marketing term used to draw more people into the practice of sustainable design has yet to be seen.

Image source: Esri Press.

Ancient Gardens of Sigiriya, Sri Lanka

View of entry gardens leading up to the rock fortress of Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Barnard Gagnon. Source: Wikipedia. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation License.

In 2003, I visited Sigiriya while on a field study abroad in grad school. At the time, I was struck by the formal similarities between it and the Renaissance gardens I was learning about in landscape history classes, despite Sigiriya having been built more than a millennium earlier. I was also struck by the apparent ingenuity and technical ability of these ancient builders in shaping the land and hydrologic systems. The gardens not only feature fountains that function to this day, but the surrounding area, which is located on the highlands in the central part of the island, features ancient aqueducts used to capture water for agricultural irrigation.

Aerial view of the gardens at Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Chamal M. Source: Wikipedia. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation License

Aerial view of the gardens at Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Chamal M. Source: Wikipedia. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation License

Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) is an island nation about the size of Ireland located in the Indian Ocean just offshore from India. It’s most familiar to modern-day Americans for its long-running civil war that ended in May of 2009 and for being the cultural homeland of London-born rapper M.I.A. Sigiriya is a UNESCO World Heritage site located in the central portion of the island. Dating from the fifth century A.C.E., the site has two main sections: the palace/fortress built on a solitary rocky hill that rises up prominently in the landscape, and the symmetrical gardens that lead up to it. The palace/fortress itself is accessible by an enormous set of stairs, and while most of the actual palace is gone, I could still see many of its original elements including its layout, the footings of wall structures, sculptural elements (including paws remaining from an enormous lion sculpture whose yawning mouth once held a staircase), and fresco paintings of royal courtesans.

Stone stairway, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Jolie. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

Stone stairway, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Jolie. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

The garden leading up to the fortress is one of the oldest landscaped gardens in the world, and is comprised of three main elements: water features, rock features, and terraces. The garden stretches out nearly 100 yards from the hill on an east-west axis. At the time it was built, it was used not just as a place to experience but as a defensive structure. It features moats that served to defend against potential attackers. Parts of the garden are designed in the ancient Persian char bagh style, and the water features include underground hydraulic systems some of which continue to operate to this day.

Moat and gardens, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Nataraja. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

Moat and gardens, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Nataraja. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

The water gardens are also divided into three main areas. The first garden consists of a section of land surrounded by water. The second is the largest and features a long path flanked on either side by two long pools, both of which connect to serpentine streams. The water features here include fountains that still function. The third is smaller and consists of a large octagonal pool.

Terraced gardens of Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Shoka. Source: Wikipedia. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation License

Terraced gardens of Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Shoka. Source: Wikipedia. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation License

The rock gardens are at the foot of the rock hill atop which sits the main fortress. They consist of several large boulders linked by winding pathways. The large boulders once had buildings on top of them, the footings of which can still be seen. The terrace gardens are built out of the natural hills at the foot of the rock. They feature terraces rising from the boulder garden to the staircases that lead up to the main palace laid out in an approximately concentric pattern relative to the base of the rock.

Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Jolie. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. Photo by Wikimedia user Jolie. Image used under the GNU free documentation license.

The rock palace of Sigiriya, the gardens leading up to it, and the broader landscape context are worthy of study for modern-day design practitioners. Its layout, its functioning water systems, and the ancient irrigation systems still used to this day are remarkable, considering that they are for the most part more than 1500 years old.