Author: Land8: Landscape Architects Network

The Landscape Installation EVERY Facebook user Needs to Visit!

“The Disconnect” – Crater Lake by 24° Studio In today’s frantic and technology driven society, it is all too easy to become engulfed in social media. Although these virtual spheres present opportunities for people to instantly get in touch and share life experiences, in reality, nothing beats an old fashioned face-to-face conversation. Let’s face it, do we really need to see an image of the latest delicacy our pseudo-friends cooked for dinner? With their temporary installation project ‘Crater Lake’, Japanese architectural firm 24° Studio have attempted to promote the lost art of social interaction to somewhat alleviate the societal disconnect brought about by social media. This hybrid, public playscape, urban intervention, and sculpture landscape installation sustains social interaction by providing an environment where people are able to meet and absorb the beauty of the surrounding landscape with a 360° panoramic vista.

What was the inspiration? The design draws inspiration from the strong social ties forged by the local community of Kobe, the location of the installation, after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995 devastated the area and its natural surroundings. Although it shouldn’t take a natural disaster for people to socialize once again! The Structure The form of this urban intervention is what first catches the viewer’s eye – its smooth and undulating surfaces coalesce into a visually compelling appearance. The complexity of its continuous and rhythmic exterior shouldn’t go unnoticed. The frame, constructed of wood for its natural qualities and structural capacity, is in fact made up of 20 pre-assembled radial parts. Each part consists of a series of free-form ribs composed in segments with horizontal support and cross bracing for rigidity. The gentle slope the frame creates provides a variety of open and unconstrained settings allowing people of multiple generations to socialize through engagement with the structure. Form follows function Whether it serves as a playspace, for sun shading/sun bathing, for breeze protection, or simply as a communal space used for the dying art of conversation. Although ultimately directed towards adults, it presents an enticing invitation to cavort for kids. Every surface of this playable sculpture can be utilized, with space for climbing, sliding, hiding, performance, quiet play, and flexibility – the user can even reorganize the seating! Landscape installations of this nature are under recognized as an artistic medium. ‘Crater Lake’ is an exceptional example of a landscape installation with a contemporary twist, but also stands as a monument to what playgrounds can become when viewed as forms of public art. Importance of this landscape installation In 2013, living in such a fast paced and immersive digital reality has left the majority of people glued to their iPhones as though they are their ‘get out of jail free’ cards, letting social media cheat them out of wholesome life experiences day after day. Ergonomic spaces such as ‘Crater Lake’ provide opportunities for people to let go of this social disconnect and engage with one another in a fun and playful setting. Although only temporary, I vote permanency. Who knows, if these start popping up around the world, you might even be free to ‘check in’ at one all too soon – just so the world knows you are still capable of social interaction without the use of the World Wide Web! Recommended Reading:- Landscape Installation Art by Ifengspace

- Land and Environmental Art by Jeffrey Kastner

Article written by Paul McAtomney Return to Homepage

Citygarden: The Best Attraction in St. Louis

LAN writer Cameron Rodman pays a visit to Citygarden. Coming to St. Louis, I expected to be overwhelmingly impressed by the Gateway Arch and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial grounds. The American monument and National Expansion Memorial have stood the test of time representing the history of America. I was excited to learn more about my country’s history and gain some knowledge of how westward expansion advanced. Instead, upon my visit, I found that the new jewel in St. Louis is Citygarden, a 2.9 acre urban park. Opened in 2009, Citygarden is the newest addition to the city’s “Gateway Mall” which starts at the Mississippi River and Gateway Arch then travels west 16 blocks up into the city. The park, which was designed by Virginia-based Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects, was a joint effort between the City of St. Louis and the Gateway Foundation.

Embracing Free Play As the afternoon heat rises and work ends for the day, people begin filling the park slowly. Families come to the park with their children to play on and in the fountains which were originally designed to be aesthetic features. While other cities have grown accustomed to preventing community members from swimming in urban park fountains, the park authorities have embraced this cultural playfulness as a defining trait and accommodated the people with the appropriate staff. You won’t find the word “no” posted throughout the park’s grounds either. The fountains have become pools to the swarms of children who descend on the park each day. People play in the pools and the whimsical LED- lit splash pad day and night. The programmed lighting display in the splash pad each night is a fantastic sight to those out enjoying the nightlife. A Vibrant Community and Eye Catching Sculptures The community really makes a strong showing, socializing with one another along the granite and local yellow limestone benches, strolling hand-in-hand on the main walk, or by enjoying the numerous sculptures which populate the entire park. The sculptures throughout the park are an avant-garde display which brings humor and levity to the urban environment. Decapitated heads, giant white rabbits, metal sumo wrestlers, giant horses, and real-time video feeds which are displayed on a giant screen all add interest and provide people with opportunities for discussion and photo ops with those they care about. Meaningful Design The design and execution of the design, which is equally as impressive, provide visitors with a variety of textures, colors, scents, and more. Unrestricted by a tight civic budget, the landscape architects produced a design which cuts no corners. The park’s layout and elements serve as a reflection of the region’s geography. A high stone wall, known as ‘The River Bluffs,’ represent the city’s identity as the ‘Mound City’. ‘The Floodplain’, which is located between curving limestone walls on the north side of the park and a long curving granite seat wall on the south side, represents the bluffs of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. Related Articles:- Connecting People & Places: The Power of Tactical Urbanism & Placemaking

- Creating Incredibly Diverse Public Spaces

Rain Gardens: The Essential Guide

Rain Gardens: Embracing the Environment to Create Thoughtful Spaces. You probably know from our previous article “Permeable Paving: The Essential Guide” that it is possible to allow water to infiltrate paths and roads with the use of permeable paving. But have you ever heard of the possibility of imitating natural forest infiltration within your own garden?

What is a Rain Garden?

The rain garden, as its name suggests, is a group of planting arrangements that make use of rainwater. The rain garden is usually small and can be incorporated into pretty much any outdoor design. While rain gardens are most commonly found in residential yards, they can also be planted in parking lots and parks. They can even function by themselves as small independent gardens.

Balam Estate Rain Garden provide an effective stormwater management. Water from the rain, passes through the rain garden, and the filtered water then flow into the stormwater drain. Credit: Rogersoh, CC 3.0

- Rain gardens serve as an inexpensive method of reducing stormwater runoff volume and improving stormwater quality as they effectively absorb and reduce pollutants.

- They function like the natural absorption of rainwater in a forest or meadow, often absorbing 30 percent to 40 percent more runoff than a typical garden lawn.

- They endure the extreme moisture and concentration of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus present in stormwater runoff.

- These planting arrangements also contribute to facilitating the infiltration of clean water, therefore conserving it and recharging groundwater.

- Birds and butterflies are provided with an ideal habitat, which in its turn reduces mosquitoes and pests.

What Sort of Plants Should Be Used? In order to attain the desired outcome, one must pay attention to selecting the appropriate plants. Rain gardens work as a balance of properly engineered soils, available space, a well-studied budget, and the right type of vegetation.

Swale and Rain Garden in Traffic Triangle, near Bartrams Garden. Credit: Philadelphia Water Department, CC 2.0

- It is best if the plants used are native. A good investigation of the available local vegetation is thus needed. But native plants are not the only option, as other non-invasive species also can be planted.

- Most rain gardens are generally planted with trees, woody shrubs, or herbaceous perennials. Annuals also can be an option.

- When choosing the rain garden plants, the priority is not the seasonal aesthetics, color, or texture, but creating a garden that needs little maintenance.

- The plants should be tolerant to drought and temporary ponding of rainwater. They must also naturally have deep roots and be able to survive the stress of heavy rainfall, pollutants, and nutrient excess.

RBC Rain Garden at the London Wetland Centre Nearly a year after it opened the Rain Garden (funded by the Royal Bank of Canada) is maturing well. In the photograph is one of the creature towers to provide habitats for insects and small mammals. They have been put together with a variety of materials from slates to sticks. Credit: CC 2.0 © Copyright Marathon

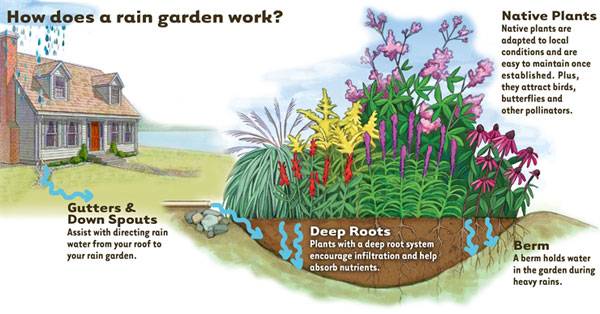

How Does a Rain Garden Work and How to Install it?

The rain garden serves its purpose by capturing rainwater from the roof or ground surfaces and allowing it to soak gradually into the ground. By doing so, the garden filters contaminants and conserves clean water, which would have been otherwise wasted in the sewer system or flooded in the streets.

Image credit: Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council.

- Rain Gardens: Managing Water Sustainably in the Garden and Designed Landscape by Andy Clayden

- Rain Gardens: Sustainable Landscaping for a Beautiful Yard and a Healthy World by Lynn M. Steiner

Article by Dalia Zein Return to Homepage Featured image: Public Domain CC 1.0, source

Awesome Education Centre Has us all Looking up in Envy

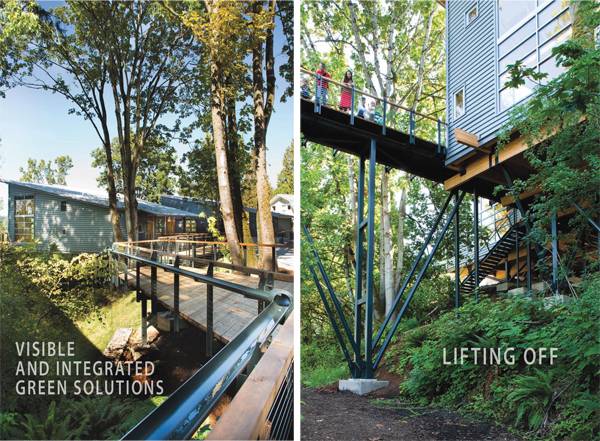

Mercer Slough Nature Park and Education Centre by Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects Buildings and nature parks: Do the two mix, or should we avoid development in sensitive landscapes altogether? Perhaps there are practical and considered ways in which we can integrate the buildings needed to encourage people to venture into the natural environment on their doorsteps. After all, persuading more people to interact with the natural world — and providing facilities in which environmental education can be spread — has to be a good thing, right? Mercer Slough Nature Park is a 320-acre park in Washington, just east of Seattle. Taking its name from the Mercer Slough River that runs through it, the park contains a diverse range of habitats, perhaps most notably a large wetland and upland forest.

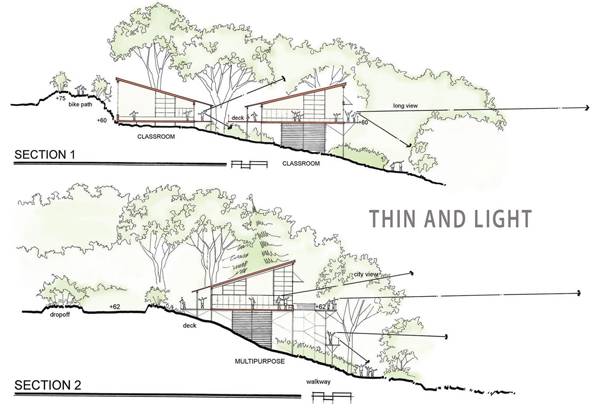

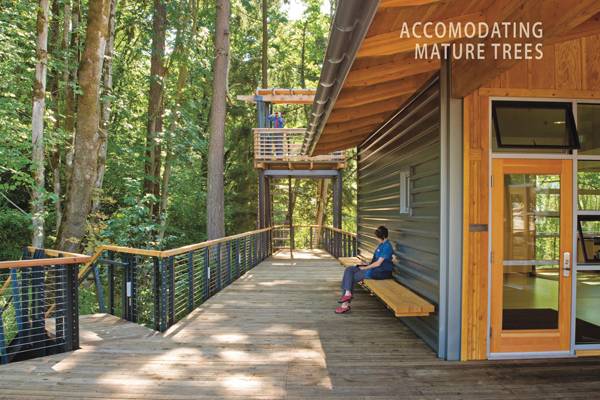

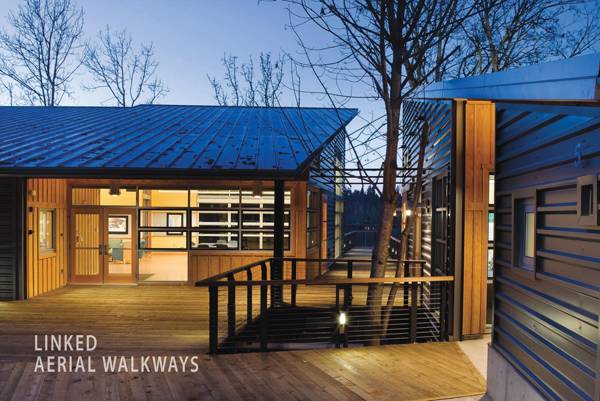

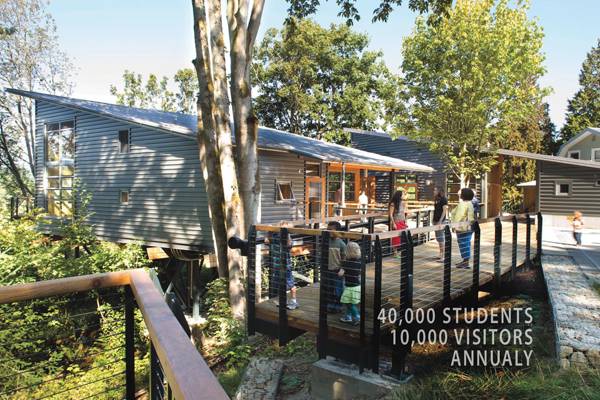

Great Opportunities for Growth and Learning This urban nature park offers local residents an opportunity to experience and learn about the natural world through a unique education center that is the product of a partnership between the City of Bellevue and the Pacific Science Centre. A Sensitive Design In a carefully considered approach to maintain the sensitive landscape, the Mercer Slough Environmental Education Centre — which could have been a single 10,000-square-foot building — rises from the ground on a series of piles, lifting it into a canopy of mature Douglas fir and maple trees and greatly reducing the building’s actual footprint on the ground to a quarter of its floor space. At the same time, its design allows water, air, and vegetation to pass beneath as they would do naturally. The center is also broken down into separate buildings to help facilitate placing it among the mature trees without damaging or removing any, retaining the tree canopy and greatly softening the structure’s impact on its setting, as well as providing a unique viewing and learning experience over the forest and wetland. A Diverse Building and Educational Experience The individual buildings include four classrooms, a multipurpose room, a visitors center, an administration building, and restrooms. These buildings are linked by a series of raised walkways that create breakout spaces and plazas where they intersect, providing accessible outdoor space and increasing users’ interaction with their surroundings. These outdoor walkways and a multitude of floor-to-ceiling windows in the various buildings provide excellent viewing and discovery opportunities out into the surrounding forest. Related Articles on Aerial Walkways:- Sensational Winding Tree Canopy Walkway

- A Path in the Forest: Tree Top Walk Creates Awesome Forest Experience

- Top 10 Pedestrian Bridges

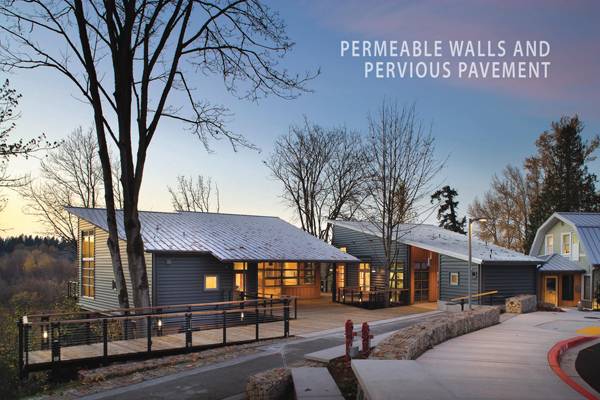

Designed by Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects, the design also focuses on slowing down storm water runoff without changing the water’s natural course. This is done via a combination of permeable walls and pervious concrete paving at the entrance plaza and rills leading rainwater collected on the building roofs to gabion splash blocks on the forest floor below.

“If you build it, they will come” – Field of Dreams The center welcomes 40,000 students and 10,000 visitors annually, including adults, families, and scientists alike, through a range of activities and resources. Ventures such as the Mercer Slough Environmental Education Centre are a fantastic and unique way of providing information and memorable experiences to local people who are interested in the environment, and can teach a wide range of community groups about the importance of sensitive landscapes, such as urban wetlands, to ensure their ongoing preservation and enjoyment.

J R Mercer Slough takes in 40,000 visitors annually. Credit: Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects

Why Grass Belongs on Your Roof and Not Just in Your Garden

Green Roof Design by Spanish based firm ON-A architects. “Go Green” — the phrase sounds impractical when dealing with trends and technology, but ON-A architects has managed to merge contemporary housing with nature in this single family house — designed by architects Jordi Fernández and Eduardo Gutiérrez in Barcelona, Spain. This recent project consists of a mind-blowing sustainable and eco-friendly environment, both inside and out. It forms an inner envelope of circulating fresh oxygen with well-conditioned comfort, providing its occupants with an extremely natural space — like hibernating under a lawn of wonders.

The Surrounding Area and Natural Perks This simple detached house lies in the characteristic landscapes of the plain of Vic, in the town of Tona. The house, opaque to the street, opens fully to views of the river and Tona Castle, providing privacy from passersby and a largesse of view for the occupants. The plain of Vic (plana de Vic) is a 30km long depression at the eastern end of the Catalan central depression in the Osano comarca. It is named after the town Vic, an important and ancient urban center. Other significant towns in the plain are Manlleu and Tona. The plain is subject to a phenomenon of thermal inversion, especially marked on calm weather days during the fall and winter, in which the surrounding mountain ranges are often warmer than the plain. This inversion in temperature is reflected in the vegetation. The original vegetation of the plain was Oak forest, but little is left owing to continuous human intervention since ancient times. Some very ancient oaks have been preserved as a tourist attraction. The Unique Design of The House The house has a C-shaped geometry that folds in on itself. The main facade is covered with vegetation in continuity with the landscaping of the plot. I hope the architect has decided to reveal the meaning “calligraphy of nature” through the representation of the letter C in this design, since this project holds itself to be an eco-friendly one in all aspects, a home that is camouflaged, with a simple wave of geometry toward its neighbors, with its compact design that seeks maximum energy efficiency. The Site The project occupies a surface of 140 square meters over the plain, with a proper and well-regulated use of space. The cover, which holds the vegetation, makes the project an inspiring one. The terrace not only acts as a platform, but also as a structure that gives the house a complete geometry, providing space for the occupants to enjoy the view of the river through a glimmer of the lawn in the back yard. The garden is a well-planned grassplot, providing continuity for the occupants with a view over the river like an infinite freehold. The access leads the user to the house through a pattern of small rectangular spots. Planning Aspects The planning of the house is well prepared by the architects, providing well-utilized spaces and better circulation. The living room merges with a dining area at the rear of the house, allowing all of the family members to gather and spend time talking with one another. The rear of the house also holds a master bedroom with a view over the river. The patio on the west side of the house brings in the rays of sunlight during dusk, illuminating the interior. The morning face of the house is blessed with illumination by the wide opening provided on the east side. Related Articles:- Why Should You Have a Grass Roof?

- What Makes a Biophilic City?

- Going Vertical: The History of Green Walls

Street Tree Survival Guide

Street trees play an important role in our urban environment: filtering air pollution, mitigating wind effects, stormwater attenuation, and decreasing the urban albedo. Not to mention the more subjective benefits of aesthetics, improved quality of life and increased property prices. It is perhaps shocking then that the University of Pennsylvania places street tree mortality 8-10 years after planting at a staggering 57%, and the average life expectancy of a street tree in London is just 10 years. The Greater London Authority estimates that there are just under 500,000 street trees in London. Some of these trees were planted by the Victorians over 100 years ago. So why are so many newly planted trees in our urban environment dying, and what can we do to ensure new street trees thrive?

Street trees; why are they dying? Photo: Source. licensed under CC 1.0

Built up urban areas leave little room for good root systems. Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris. Credit: CC BY-SA 2.0, by Aleksandr Zykov

Stunning Residential Development Brings The Beach to The Residents

Baan San Kraam by Sanitas Studio The Baan San Kraam residential development completed in December 2013, in Cha-Am, Petchaburi, Thailand encompasses 266 units. Out of the 13 buildings in the master plan, only two have direct views to the Cha-Am beach. The designers were faced with a specific and unique challenge: bring the beach to the remaining 90% of the development that does not border the ocean. The overarching concept was to create a holistic setting that mimics the seascape. Designers allowed the nautical theme to influence every aspect of the site design including circulation, vegetation, topography, and building orientation. The Vision: The design team was charged with integrating the beach theme into the entire residential development. The vision was to create unique zones so each area expressed a different theme mimicking natural ecosystems and regions of the ocean. The buildings are divided into seven clusters, each modeling a unique oceanic element. Visitors are introduced to the nautical notions upon arrival and it flows continuously through the village tree house, the floating house, modern jungle, and fisherman village themed areas.

Design is in Details Successful deployment of this concept is due to the careful attention to detail design. In the initial site plan, designers made a point to preserve existing trees as specimens and focal points in the landscape. New vegetation selected for the planting plan includes all local coastal plants. The plant material divides the zones and helps to differentiate each themed area. Carefully selected plants provide shade and decrease the ambient temperature while providing unique experiences for the seafaring residents. Landscape lighting highlights the use of coastal plants and accents the landscape design. At nighttime, the residential development looks much like a high-end beachfront resort featuring sparkling pools and lush vegetated swatches. Use of Water in the Design The waterbody is the central organizing system, or the spine, of the community. Water is the dominant element of the development and it connects all zones together. With water as the focus, all other systems and buildings are oriented along this datum. Pedestrian circulation transitions from paved pathways to boardwalks as it spans sections of the waterbody. Rock stepping-stones delineate secondary paths through the residential development. These pathways are more informal and lead to building entrances or private terraces. Flow From Water to Land Islands act as punctuation marks in the waterbody subdividing spaces, providing areas for lush vegetation, and adding authenticity to the ocean-like forms. Private access to the islands is granted along a stepping-stone pathway. Grading changes around the buildings were based on the topography of the pool. Much like lines in the sand, or ledges in the ocean floor, distinct lines on the floor of the waterbody indicate changes in water depth. The lines representing a change in topography in the pool extend into the landscape providing a natural exemplification of a seaside setting. Integration of all community systems such as building orientation, topography, and circulation, allows for a more holistic and authentic experience. Rest and Relaxation Another element of the residential development influenced by the nautical theme is seating. Lounge chairs are clustered along the edge of the waterbody in the way that chairs are found on the shore of a sandy beach. Some are gathered in a group-like settings as seen near a beach cabaña whereas others are in more private and secluded areas meant for families, individuals, or residents that live adjacent to the space. Other seating areas are carefully designed into the walls that define and divide zones and spaces. The seamless integration of seating in the beach-like setting allows residents and visitors to embrace and enjoy the serene and continuous oasis. Each rounded balcony provides premier views to the ocean-like landscape encircling the residential development. The ocean journey begins upon arrival and the theme is carefully woven into each zone and every aspect of the site and detail design. The successful execution of the ocean concept is due to the research and careful observation by designers of the adjoining beach. The result is a residential development that realistically emulates elements of the natural seascape. Recommended Reading: Pools and Spas: Everything You Need to Know to Design and Landscape a Pool by Editors of Sunset Books Article written by Rachel Kruse Return to Homepage View LAN’s most popular articles HERE!Geocaching: Treasure Hunting For BIG Kids!

Exploring the landscape in the 21st Century There are many ways to get out into the landscape and explore new places. Geocaching is an exciting and innovative way of exploring the landscape in search of hidden objects called caches. How does geocaching work? Geocaching relies on either a GPS unit or a GPS enabled device such as a smart phone. An object is hidden in the landscape or urban streetscape with a GPS sending device or tag. The person or people participating then have to find this cache using their device. The first to find the object wins. Geocaching can also be done non-competitively by simply looking for the objects at your own pace. WATCH: What is Geocaching? There are many apps you can download on Apple, Android and Windows platforms for using on your smart phone, so it’s a very accessible way of having fun in the landscape. Often, these apps are provided by geocaching organisers who have either hidden their own caches, or their members have submitted a geocache to their website. Currently there are over 2,000,000 such caches around the world. Related articles:

Often geocaches are hidden in weather proof containers that also contain a log book for the geocacher to write their name or tag (a geocaching nickname) along with the date they found the geocache. Occasionally geocaches contain a small trinket or memoire to trade. In these cases it is expected that the object is replaced by another similar object of low value for trading with the next geocacher.

Who can geocache? Anyone who is reasonably fit and has a good mobility can geocache. Objects are hidden in a range of places with varying degrees of accessibility; from a street in your local neighbourhood to rugged mountain trails. You can simply pick the sites you want to visit. Why geocache?

Two geocachers with a geocache they have found. Credit: CC BY-SA 2.0 by Fihu

Creating Incredibly Diverse Public Spaces

What should public space be? How should it function, and what should it look like? These are some of the major challenges facing a landscape architect approaching a new public space project. Everyone has their own opinion, and they’re entitled to it but I don’t believe there is currently a right answer. Instead, it would increasingly seem that public spaces can no longer simply be ‘attractive’ or serve a single function such as providing office workers with somewhere to eat lunch. Instead they must also be: sustainable; low-cost; environmentally friendly; safe; accessible to all; inclusive of all user groups; increase biodiversity; aid rainwater drainage; provide social, economic and environmental benefits, et cetera, et cetera… But how, if at all possible, can we tick all of the boxes? No One Solution Fits All Of course, each site is unique and should be designed based on individual case needs and circumstances, but many will have one thing in common: the requirement to maximise the use and potential of precious public space. Maybe that’s easier said than done but innovative ways of delivering multi-functional public spaces are springing up all the time. We can also learn a lot from some of the successful examples of public places that have been around for a while, places that are able to adapt to changing needs and still provide multiple functions to multiple users. Here’s one prime example: The city of Portland, Oregon seems to have it figured out with Pioneer Courthouse Square. Located in the heart of downtown Portland, the city’s main urban park is known as ‘The city’s living room’ and attracts around 10 million visitors per year.

An Electric Hub of Activity Surrounded by 4 blocks of shopping, dining, entertainment and business, the square is an ideal gathering, meeting or resting spot. The key to its success is seemingly its pro-active management, prime location and simple design. Instead of filling the square with clutter and trying to define its function, the design is fairly minimal, retaining a large flexible space at its centre which is used to put on a busy events schedule (322 last year) and thus providing entertainment, interest and above all a reason to keep going back, for a range of tourists and locals alike. The layout cleverly uses the slope of the land to facilitate the use of steps which provide amphitheatre style seating around one corner and two sides of the square, allowing for a large number of spectators at any one time. The square is home to a transport office within the tourist information and travel office and is well served by transport options. The flagship Starbucks store sits on one corner in its home city, but all other vendors are mobile, allowing further flexibility in the squares service offerings. Maximising Green Space Whilst there is not an abundance of ‘green space’ in this urban park, trees line the edges of the square to provide shade and shelter and plant pots are regularly brought in to add colour and life to contrast the red bricks that dominate the design. The calendar of events includes: cinema, international festivals, concerts, markets and many more which mark the square out as a prime attraction, year round. The events also generate income for the continuing operation of the square. It is well looked after, with a team of janitors and security guards maintaining cleanliness and security. Thinking About The Future In the case of Pioneer Courthouse Square, it would appear that staying flexible, or not trying to prescribe function, allows it to actually serve multiple functions. The design element did not finish when the square opened in 1984, instead a management trust was set up to manage it on an ongoing basis, ensuring it continually delivers on its aims to activate and enrich the environment of the park to serve the people of Portland and its visitors. Watch: Pioneer Courthouse Square & Pioneer Place So if you’re struggling to fit a vegetable garden, wildflower meadow, play equipment, rain garden, urban forest and ample seating into your next design project, just remember that sometimes, less is more. Recommended reading: Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space by Jan Gehl Insurgent Public Space: Guerrilla Urbanism and the Remaking of Contemporary Cities by Jeffrey Hou Article written by Simon Vive Return to HomepageBiomimicry UK: Interview with Richard James MacCowan

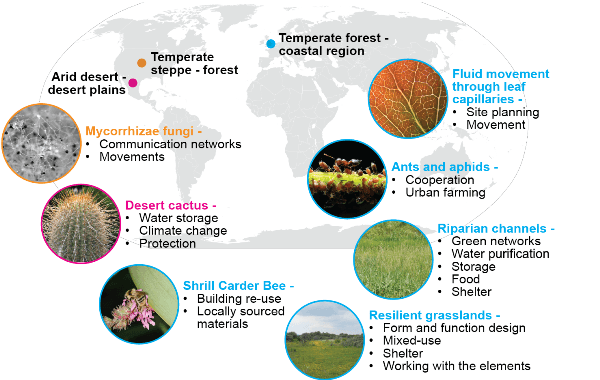

Richard James MacCowan is a co-founder of Biomimicry UK. He recently completed his master’s degree in urban design at Leeds Metropolitan University, where he is now a Ph.D. researcher and part-time lecturer. His research focuses on using biomimicry as a tool in ecological design. Hi, Richard. Thanks very much for talking to us here at LAN. Let’s dive right in. Perhaps you could begin by telling us what biomimicry is? To borrow from notable academics, I would say biomimicry is the conscious emulation of nature’s genius. It’s looking at how we can mimic the form, processes of systems of nature to provide us with more resilient solutions. I say solutions instead of design, as using nature as inspiration is being used across many fields, ranging from landscape architecture through to economics.

And what is the purpose of Biomimicry UK? The purpose of our network is to provide a way to bring together students, researchers, academics, and professionals who are either interested in this evolving field or are currently practising biomimicry. We are not exclusive, so we are covering not only the well-known fields linked to biomimicry, but also business and economics. Our longer-term goal is to link more research institutions together to develop stronger links with industries looking for more innovative strategies that they cannot develop due to time and cost constraints. Who else is working on Biomimcry UK with you? The other co-founders are David Sanchez, a Ph.D. researcher at the University of Dundee, and Annette Schumer of Biomimicry NL. We have three “champions” of biomimicry: Julian Vincent, honorary professor of biomimetic engineering at University of Bath; Giles Hutchins (co-founder, Business Inspired By Nature) ; and Michael Pawlyn, founder of Exploration Architecture. What are the benefits of biomimetic design? People see a lot of things as cost value. But social well being has cost value, too. If we are innovative and follow what nature does successfully, this will have knock-on effects by reducing costs and environmental impact and benefiting our own social well being. If, for example, we develop more SUDS in cities, we have the social benefit of being closer to nature and the sound of running water. And is this something you’ve incorporated into your own work? My project (The Gas Works, Canvey: Using the principles of Biomimicry to develop an Urban Design Framework on Canvey Island) looked at a site on Canvey Island, which is currently used for all the major gas that is brought into the country. I looked at the island’s ecosystems and organisms, particularly Canvey Wick – one of the country’s most biodiverse habitats for insects. By looking at Canvey Wick, I was able to see how resilient ecosystems work, from the smallest ant to the largest tree. This enabled me to develop a continuous-loop system to minimize the impact a large-scale development would have on the island’s infrastructure. I was lucky enough to win the Student Prize at the 2013 National Urban Design Awards and the Fraser Teal Award from Gillespies. This systems approach is something I am developing for my Ph.D. So what other projects are on the horizon for Biomimicry UK? At present, we are developing our on-line presence and applying to be linked to Biomimicry 3.8 in the USA. David Sanchez and I are part of a steering group to develop a “Biomimicry Self-Build Project” with Resonate Arts House in Alloa, Scotland. In addition, I recently ran a workshop at the Global Biomimicry Conference on systems thinking. We used real challenges given to us by companies from both in the UK and USA. This will allow us to develop links to industry to promote biomimetic thinking. Currently, I am arranging workshops with both the York and Leeds Green Drinks events to be held on the 18th and 23rd July, respectively. Thanks, Richard. Lastly, do you have any favorite fascinating projects that use biomimicry to tantalize our readers? The one that I keep going back to is the Silk Pavilion by the MIT Media Lab. (This project explores the relationship between digital design and biological fabrication in terms of product and architectural scales). Just watch the video! It’s incredible. Also, Airbus are developing some interesting projects, from materials to minimize cleaning in bathrooms based on the lotus leaf, to sharks’ skin to achieve drag reduction in airplanes. Finally, for the landscape architects, Living Machines, based in the USA, have developed systems to clean water based on the tidal flow of a wetland. Once again, thanks so much for talking to us, Richard. If any of our readers are interested in what you’ve read today, more information on Biomimicry UK can be found on their Facebook Page and on Twiter (@Biomimicry_UK). Recommended reading: Biomimicry: Inventions Inspired by Nature by Dora Lee The Shark’s Paintbrush: Biomimicry and How Nature is Inspiring Innovation by Jay Harman Interview conducted by Sonia Jackett Return to Homepage Featured image: Credit: Kevin Krejci, source ; Water Droplets on LeafNaples Gridshell Urban Furniture Experiment

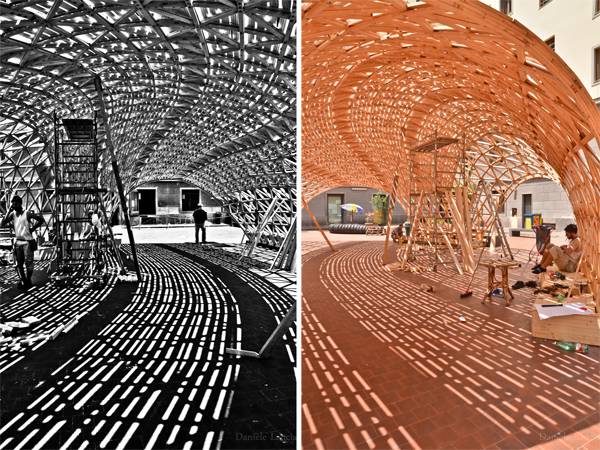

Gridshell, a timber structure, built for Naples School of Architecture courtyard, University of Naples”Federico II” by Gridshell.it What happens when the spaces we visit the most, or the spaces where we spend the most time always look the same? We get bored because nothing changes-neither the architecture, nor the furniture. When there’s nothing new to appreciate or discover we tend to see the area as an empty and boring place; and turn it into the last place we would like to linger. But when we find a way to innovate (even with a small change such as adding new furniture, color, textures or new lighting), that empty space could turn into an iconic place. Something fresh and new can make all the difference in bringing life and comfort to any space. The possibilities are endless, given the resources at our disposal, and how we could use them. What happens when we students decide to bring our knowledge out of the classroom and into the campus? What happens when we decide to commit to a sustainable practice, and invite people to get involved? That’s exactly what a group of master’s degree students has done in Naples, Italy at the Naples School of Architecture. They decided to combine teaching and research in a construction experiment, focusing on developing a structure that could be used as a piece of urban furniture, with the goal of sustainability and innovative construction. The result was a gridshells made of wood.

Eco-compatibility, Affordability, and Construction What’s the project about? The students decided to build a gridshell on their campus to investigate the Eco-compatibility, affordability and the ease of construction of such an urban intervention. The 96 square meter gridshell was built of coppice wood materials from the Italian forest (all certified). The use of this material guaranteed that no glue or chemicals were needed in the construction. Construction How was it built and by whom? The gridshell was constructed in situ in the courtyard of the Naples School of Architecture, with students taking straight pieces of wood and bending them along geodesic lines. The wood had been cut and prepared in a workshop previously. The hand tools the students used were the same as any carpenter would use in their work. The project was both designed and built by students. This entailed assuming the role of carpenter giving them the chance to accumulate practical experience that was extremely valuable for their understanding of the physical properties of the material as well as the mechanics of the structure. The construction was an open project that attracted attention from people around the campus. Other students, teachers and local residents were also invited to join in. The research team and the new recruits grew day by day turning a scholarly project into a community experiment. The Play of Light and Shadow After the gridshell’s construction, the Faculty Council decided to add a shaded area for students in one of the faculty courtyards under the gridshell. They added a wooden skin to the structure, resulting in playful geometric shadows, turning the courtyard into a new and comfortable space where students, teachers, and others could sit and have a coffee while reading, enjoying conversation, or taking a rest. A skin made of wood was added to the main structure to cover the space. This skin was applied systematically across the length of the structure. The cladding method has resulted in playful geometric shadows, turning the courtyards into a new and comfortable space. See also: Sun Salutation and The Sea Organ Stunning Plant Pavilion Created in China A New Green Era in Construction Once again, this project shows the importance of developing an eco-friendly construction system utilizing easy to handle materials that don’t involve artificial chemistry or substances dangerous to the environment. It’s easier for anyone to participate in this kind of construction when we don’t depend on technology. This is an innovative way to build urban spaces, as well make sustainability the focus of the project. Watch: Digital Form-Finding of Timber Post-formed Gridshell – The video below gives you an understanding of the design and build process. Projects that are easy to construct and inspire community involvement, that’s what we need, as we move forward to a new “green” age, where the most important thing is to stay healthy while promoting a healthy environment. Project credits: Name: Toledo Gridshell A timber Gridshell, built for Naples School of Architecture courtyard, University of Naples”Federico II” (2012) Project team: Arch. Andrea Fiore, Arch. Daniele Lancia, Prof. Arch. Sergio Pone, Prof. Arch. Sofia Colabella, Arch. Bianca Parenti Structural Consultants: Arch. Bernardino D’Amico, Prof. Ing. Francesco Portioli. Recommended reading: Ecological Design, Tenth Anniversary Edition by Sim Van der Ryn Principles of Ecological Landscape Design by Travis Beck Article written by Maria Conchita Sandigo Return to Homepage Featured image: Credit: Daniele LanciaSketchy Saturday | 026

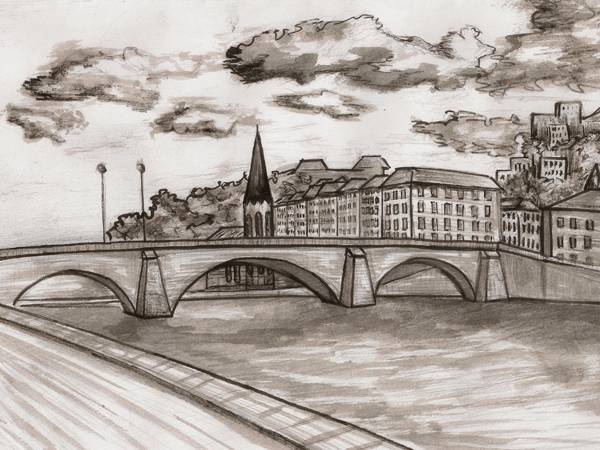

This week’s Sketchy Saturday top 10. Welcome to what is becoming one of the world’s biggest databases of sketches online. Featuring hand drawn talent from the all over the globe. Every day you guys send us in your sketches, showing your latest creations and in some cases forgotten work which you have blown the dust of to submit to us, something we are really grateful for. This week we seen an array of fabulous work that is sure to inspire as it reminds us all why hand skills are still an integral part of being a designer, especially when it comes to designing outdoor spaces. 10. by Shamsul Johari B. Shaari, UPM-MLA

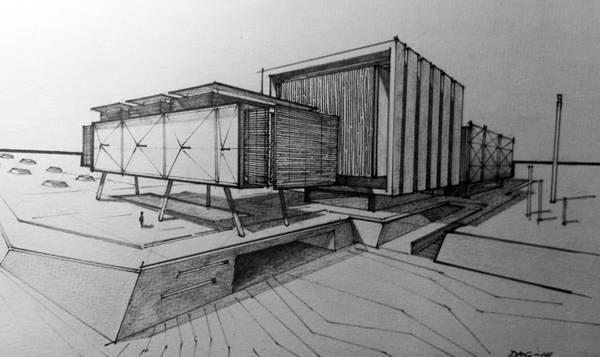

“This drawing is part of my proposal for my urban design subject in MLA in University Putra, Malaysia. I tried to imagine the space, elements and functions of the area in a way that would give the people more use of the public space. This area needed linkage from the Clock Tower to the Mosque (Jamek) in the centre of Kuala Lumpur. I used a drawing pad, tracing paper, photostat and mix of colours (ecoline + pencil colour)”. 9. by Münire SAĞAT “I made this sketch for the Losev Natural Living Center competition. The area is a natural life village in Cankiri Cerkes. I drew it by promarker on white sheet. Therefore, I had an aksonopmetrik perspective. I am a landscape architect at my own firm; Studio BEMS Landscape Architecture and Urban Design in the capital city of Turkey, Ankara”. 8. by Roman Oravec Landscape architecture MA student – Slovak University of Agriculture – Slovakia4. by Brett Freeman, graduate student of Architecture at the Univ. of South Florida, School of Architecture and Community Design, USA “The watercolor rendering is the result of an Urban Design assignment to conceive a high density block in St. Petersburg, FL, whereby public space is shared with both residents of the block and those shopping or passing through by foot or bicycle: a destination as well as a vibrant, urban street. Materials are watercolors on watercolor paper and black prismacolor pencil for some edges, to make them pop”.

“This sketch is to show the owner in 3D how all the elements in this garden relate to each other. This 2 point perspective drawing is made on a professional drawing board on tracing paper, then copied on thick drawing paper. The last step was drawing the design all over again with a soft pencil, fingers and smudging stick”.

That’s this week’s Sketchy Saturday top 10, congratulations to all of you who featured, it really is a challenging task, with so much awesome talent out there. Check out the Sketchy Saturday official Facebook album and see literally 1,000′s of incredible sketches! Follow all the winning entries on our dedicated Sketchy Saturday Pinterest page. If you want to take part send your entries into us at office@landarchs.com Recommended reading: Sketching from the Imagination: An Insight into Creative Drawing by 3DTotal Article written by Scott D. Renwick Return to Homepage Featured image: Lim Yee Zhing, Architecture Student ,Malaysia