Author: steve austin

Landscape Architecture Education: Between Two Worlds

For over 30 years in various capacities, I have taught the profession and craft of landscape architecture to university students. Sharing my love and passion for landscape architecture with students has been one of the great joys of my life. The academic, professional, and community recognition they have received for their individual and team work gives me great personal satisfaction. Yet with all this, I now wonder if I am adequately preparing my students for their future.

Our current students will face challenges unlike any faced by previous generations. Anthropogenic destruction of life and life-support systems has pushed the planet into an ecological emergency. Mass extinctions are accelerating. Human encroachment into the last wild places has given us the global pandemic.

And from the ecological emergency arise social emergencies. The botched US response to that pandemic coupled with an already wildly unequal economy may have created a depression that could last a decade. At the same time, the protectors and purveyors of systemic racism in the US seem hell bent on ensuring the country disintegrates into violence and hatred rather than see any challenge to White rule for the benefit of corporations.

Oh, almost forgot: 2020 will likely be the hottest year in recorded history, following the hottest decade in recorded history. Global heating has already triggered 9 of the 15 known tipping points of the planetary regulating system, potentially leading to a cascade of unstoppable, devastating climactic events. These could destabilize living conditions over large swaths of the planet, causing immense human suffering and likely leading to sustained global military conflict over the coming decades. Leading climate scientists recently published a paper in the journal Nature which concluded that “this is an existential threat to civilization.”

So yeah, today’s students got all that going for them, which is not nice.

How are we addressing this as landscape architecture educators? While much of landscape architectural education is timeless, I fear it is not evolving as urgently as the emergency demands. A great deal of today’s curriculum would be recognized by students of 50 years ago or longer and is suited for a planet and society that no longer exists.

There are so many ways in which our educational efforts need to progress – placing social and environmental justice at the absolute forefront of our work perhaps being chief among them. This means moving landscape architecture beyond what practitioner and educator Kate Orff sees as a narrow “realm of professional services.”

Concurring with that, Billy Fleming, the Director of Penn’s McHarg Center, has written that we must “reconstitute our discipline as something more than a client-driven enterprise” focused primarily only on sites. He directly challenges current landscape architectural education when he writes: “Can landscape architecture be both an instrument of neoliberalism and an activist force in the fights against climate change and for social justice? If it can’t, we need to find new ways of imagining our mission and disciplinary scope.” Among other things, this would involve creating “alternative models of practice in landscape architecture” involving training “a rising generation of landscape architects for careers in public service.”

Another vital way our educational efforts need to progress has to do with our relationship to energy. Our current educational system is premised on having essentially unlimited amounts of fossil fuels to enable our work. Climate science tells us that in order to do our best to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of global heating, we must end the use of fossil fuels within 20 years. Ending fossil fuels will absolutely transform society, and thus our profession. And if we don’t stop using them, then we likely will have locked in heating that may be undoable, leading to catastrophic conditions.

Either way, everything will change.

Regarding this, climate activist Rupert Read writes, “This civilization is coming to an end. Our societies need to transform ways of living so drastically that even if we prevent collapse the civilization that emerges will no longer be recognizable as this civilization.”

20 years is mid-career for students who are currently enrolled in landscape architecture programs. I worry that we are training them for a world that won’t exist then. This reality gives me a great deal of cognitive dissonance as an educator.

Thus we are – right now – between two worlds: an old one where we were confident of how the future would unfold and a new one where the only certainty is that radical transformations are on the way.

Therefore my dissonance: for which world are we teaching?

Ultimately, I am an optimist. I believe that we should educate students to be of use for the world where we come together globally to end fossil fuels, do everything possible to restore a livable climate, and stop the destruction of planetary life and life support systems. This is social and ecological justice, the very soul of Frederick Law Olmsted’s understanding of what this profession could be.

Doing this will be daunting. Alternatively, I guess we could educate students for a world where acceptance of, and attempted adaptation to, climate disaster and environmental destruction is the mainstream response. This seems to be the current default position. However, landscape architects should want no part of a world that simply accepts the greatest human rights violation ever perpetrated.

I believe – but maybe it’s just a hope – that landscape architecture is an instrument greatly needed to help us to reverse these crises. If it is to be, we have to get real about teaching to the new realities ASAP. The longer it takes us, the more planetary systemic disruptions will occur, which will make it that much harder for today’s students to succeed. I will do my part to help them.

—

Image: Licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.; 2018 year end Landscape Architecture Student Review on Friday, April 27, 2018 in the LA studios on the second floor of the E.S. Good Barn on the campus of the University of Kentucky.

Landscape Architecture and the Zero Generation

As the climate crisis intensifies and accelerates, a new generation of activists is emerging with startling suddenness. In an effort to stem this crisis, many young people are mobilizing rapidly.

Members of this group, styled “Generation Z,” were born within the last 25 years. Although derided by some as “snowflakes,” these young people are the largest generation in history. Bloomberg reports Generation Z will comprise “32 percent of the global population of 7.7 billion in 2019, nudging ahead of millennials, who will account for a 31.5 percent share.”

In the US, this is a group that understands climate change. According to recent study by the Harvard Political Review, “Over 70 percent of the Gen Zers polled…agree that climate change is a problem, 66 percent of whom think it is a crisis and demands urgent action

This large a group, and one whose overwhelming majority understands the issues, will hold enormous power. Appreciating their activism would serve landscape architects very well in the coming years. After all, they represent the future of the profession as practitioners, clients, and users.

Generation Z is the first generation to have seen the effects of the climate crisis for their entire – albeit short, so far – lives. Because of this, they understand climate change, and the associated ecological breakdown, as imperiling not just their economic and social futures, but their very existence. This has created a great sense of urgency among many of them, leading to stunningly impactful actions within just the last few months.

For example, it was less than 10 months ago that the then 15-year-old Greta Thunberg staged a solo protest at Sweden’s parliament to force action on global warming. Since then, her School Strike for Climate has inspired millions of students around the world to do the same, and given her message significant global audiences.

In the UK, the multi-generational but youthful Extinction Rebellion’s non-violent protests in April of 2019 led the British Parliament to declare a “climate emergency“, the first democratically elected government in the world to do so. At the same time,the UK government’s chief climate advisory agency recommended for the first time an accelerated plan to cut the country’s carbon emissions to zero by 2050. Soon thereafter, Ireland’s parliament became the second national government to declare a climate emergency. They have been joined by hundreds of local and regional governments around the world.

In the US, the youth-led Sunrise Movement has gained momentum, discussing climate change in “classrooms, living rooms, and worship halls across the country” and providing support for the Green New Deal. And Juliana v. US, a lawsuit filed by 21 young plaintiffs against the US government is proceeding. The young people allege that “through the government’s …actions that cause climate change, it has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resources.”

However, the current Administration’s Department of Justice has responded to the suit by demanding that it be dismissed, stating:“there is no right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life …because such a right is entirely without basis in this Nation’s history or tradition.”

Felton Davis cc-by-2.0

A Vision of the Future

Undaunted by such callousness, the young activists are clear on one thing: they have accepted the climate science that warns that there is little time left to keep global temperatures from rising more than 1.5C, beyond which climate catastrophe looms.

To avoid this, the laws of physics require that humanity cut greenhouse emissions by 45% within a decade and reach zero use by 2050. Thus “Generation Z” must become the “Zero Generation.” In order to achieve that, the youth of today will “have lifetime carbon budgets almost 90% lower than someone born in 1950.” And most of that budget will be used in their youth: by the time they reach middle age, the Zero Generation will have no more carbon to burn.

If these young people succeed in helping us to avert the worst of the climate crisis, they will usher in completely new paradigms for landscape architecture. The end of carbon dioxide emissions means the end of fossil fuel use. Unfortunately, the contemporary work of landscape architecture is thoroughly soaked in fossil fuels. Not using them will change the way we approach design and education, as well as our materials and construction methods, how our projects are maintained and even our ethics. Further, the need to drawdown excess CO2 from the atmosphere will require new approaches to every project. Read more about Post-Carbon Landscape Architecture on Land8.

In light of all this, how will landscape architecture respond to the youth of today? Positively, the goals of our work should be broadly attractive to the Zero Generation; landscape architecture offers so many possibilities for both mitigating, and adapting to, the climate crisis. This should provide us with great support in terms of new practitioners, clients and users.

But to ensure that we do not perpetuate the intergenerational injustice of climate change, then we must truly align our work to the zero fossil fuels reality. This is not an issue that is going away or that will somehow get better on its own. It will require enormous changes. We should be leaders ourselves, not waiting on our children to push us.

In the words of Greta Thunberg, “I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.”

—

Lead Image: David Tong CC BY-SA 4.0

Post Carbon Landscape Architecture

Background

Here in early 2019, we find ourselves in a terrifying time. The evidence is astoundingly clear that the effects of climate change are worse than previously predicted and accelerating. If humanity is to avoid catastrophic, perhaps even unsurvivable climate change, we must end the use of fossil fuels as soon as possible.

However, if we were to do that, the resulting energy and civilizational transition would be the most dramatic ever undertaken by our species. Everything about our current way of life would change greatly.

But scientists are emphatic about the need to end using fossil fuels now. Prof David Reay, of the University of Edinburgh, says we must “act now or see the last chance for a safer climate future ebb away.”

The end of fossil fuels will usher in a “post carbon” era. It is “post carbon” because we can no longer do anything that releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, especially through burning fossil fuels.

Landscape architects must accept this reality.

Please understand that this is absolutely different than things labeled “green,” “sustainable,” “low carbon,” or even “net-zero.”

Post carbon landscape architecture means that there will be no use of fossil fuels for construction, transportation, or even the creation of many of the materials commonly used by landscape architects.

Obviously, this will fundamentally change our work.

Reaffirming what we do

Yet we must assume that the need for our work will only increase in the future. Therefore, it is imperative to state exactly what it is that landscape architecture should do.

Below is an initial attempt at descriptions of the broad ways in which landscape architecture will be essential in the post-carbon era.

- We are needed to design and build beautiful places that will nurture the healing and growth of authentic human communities and individual spirits.

- We are needed to help protect and restore systems that will help life to recover and flourish.

- We are needed to share our understanding of the earth’s cycles, processes and bioregions to sustainably meet our elemental needs.

- We are needed to help us creatively adapt to the challenges of the Anthropocene, such as rising sea levels, fires, droughts, human migration, habitat loss, pollution, (and unfortunately), etc.

I’m sure there are some other categorizations as well as many subsets.

The key thing is this: None of these activities intrinsically require fossil fuels.

Landscape architecture has been practiced for millennia. Certainly, much of that work was in the service of power, and the benefits were directed to elites. Nonetheless, there have been significant positive interactions with the land that did not require the use of fossil fuels. My point is that it is possible.

Take Central Park, for example. America’s greatest public space was built without fossil fuels. Instead, Olmsted’s vision of democracy-made-visible was built primarily with the muscles of animals (human and otherwise).

Central Park, 1869

It was not perfect, as demonstrated by the removal of Seneca Village, one of New York City’s few African-American middle-class communities, to make way for the park. We must never repeat such injustices. But as a symbol of what is physically possible without using fossil fuels, we can do no better than to study Central Park.

Reframing how we work

Fossil fuels have only been fully embedded in the work of landscape architecture for 100 years or so, and then only as a means to our desired ends. Our profession must now reframe our understanding of the means used to create our desired ends. What a wonderful creative challenge!

Understanding the limits of the post carbon era should be our first response. First, we will have much less energy to use. Ending fossil fuels will eliminate 80% of our current energy supply. While renewable power will no-doubt increase, it cannot replace all the energy of fossil fuels. We must break out of our 20th century “have-it-all” mindset: future energy supply will not meet our wants.

Renewables produce electricity, not fire, and only intermittently. There will be many claims on the resulting electricity distribution. This energy-limited future will require us to embrace both radical simplicity and radical sufficiency.

Next, the post carbon era will mean an end to most of the construction methods and material choices we now take for granted.

Today, landscape architects rely on fossil-fueled machines to do most of our heavy work for us. We rely on large amounts of materials, such as concrete, metals, and plastics, all of which cannot be produced without large emissions of carbon dioxide. In the post carbon future, we will have neither those machines nor much of those materials.

We must rediscover low energy and labor efficient methods. Think clever low tech, and locally sourced, appropriate materials.

All this will require us to reimagine design.

First, we must design for only those things that must be done.

In the post carbon era, we will do well to heed Olmsted’s direction that “service must precede art…” (To quibble, I would rearrange that somewhat to say that we should engage in “artful service.”)

And then we must be creative in planning and specifying construction that can be built without emissions of any sort.

Perhaps we should emulate birds. Many species build intricate, beautiful nests with only what is near, and with only what they are able to carry.

We too should practice a “small, light, and local” design and construction philosophy.

Perhaps too, we should emulate beavers – nature’s ecosystem engineers. Beavers certainly build to suit themselves – like us – but their work also benefits the life and life support systems around them. Their work is a eco-positive, unlike, too often, ours. To paraphrase and expand on Milenko Matanovic’s vision, we must work for “multiple victories” on every project.

Further, we must ensure that our projects incorporate copious plant material and soil building activities. That is not to offset our own project’s emissions, but to be able to sequester some of the excessive carbon dioxide now in the atmosphere. This is “Drawdown,” and it will be an operative principle for us from now on.

Landscape architecture education must change to facilitate this. We need an increased focus on integrated ecological design, fossil fuel free materials and construction, and the research that will support the post carbon profession.

Landscape architecture practice will necessarily change as well. In the lower energy future, distance will matter a great deal. This will not only affect our practice sheds, but our material supplies and labor force.

Finally, our ethics must evolve. Ending fossil fuels will mean a return to the use of muscles in much of our needed work (human and otherwise). We must be very aware of this reality and create the ethical standards by which to value and protect those that do the work. ASLA, for example, does not have an explicit position on labor (human and otherwise).

Additionally, we must hold ourselves accountable to more exacting standards of social and environmental justice to ensure that what we are doing is for the greatest benefit for all communities.

What won’t work

The alarms are going off. But many people, landscape architects included, assume that “solving” climate change will not require dramatic changes. There is a belief that technology can be employed to enable us to basically continue as we are now.

Unfortunately, there is no technology on the horizon that will suck from the atmosphere – at the needed scales and time frames – the excess carbon dioxide that is causing us harm and then safely lock it away deep underground, for thousands of years.

Nor is there any realistic type of geo-engineering that could somehow deflect the sun’s rays to keep us cool. Anyway, we’re already performing one scary experiment with the climate, we don’t need to add another.

So, if technology is not riding to the rescue, what other options are there?

Simply hoping for a something to work out is irresponsible. Ignoring the threat is morally indefensible. And our current baby steps to reduce carbon emissions will, to quote Alex Steffen, “guarantee defeat.”

The only realistic ways to avoid climate catastrophe are to immediately end fossil fuel use, stop deforestation, and begin vigorously restoring carbon sinks. Doing this will also give us a chance to reverse the existential damage we’ve done to the rest of life on this planet.

But what if no one else quits fossil fuels? What should landscape architects do?

Kathleen Dean Moore puts it best in reference to all of us as citizens: “If we don’t respond to the emergency, we become part of the storm itself.”

Which side of history should landscape architects be on?

Moving forward

Landscape architects are desperately needed for the future we are entering. We must recommit to do our needed things with great imagination, courage, and justice. We must support each other and our communities as we undertake this challenge. Let’s be leaders for the world as it must become.

—

Lead Image: © Steve Austin (used with permission)

The Climate Report That Changes Everything for Landscape Architecture

On October 8, 2018, the UN released a bombshell report whose implications will shake the profession of landscape architecture to its core. The report lays out clear evidence that if world governments don’t take drastic action to end the fossil fuel era over the next decade, in the very near future humanity will witness severe food shortages, climate related poverty increases, and massive ecological destruction, all leading to unprecedented human migration.

This is ultimate proof of the destructiveness of fossil fuels and the first time we’ve definitively been presented their needed expiration date.

“This report shows that we only have the slimmest of opportunities remaining to avoid unthinkable damage to the climate system that supports life as we know it,” said Amjad Abdulla, an International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) board member, in a release. Debra Roberts, co-chair of one of the IPCC working groups, is quoted as saying of our situation: “The next few years are probably the most important in our history.”

In order to maintain that slim opportunity, the report argues that the nations of the planet must soon stop burning fossil fuels to keep global temperature from increasing no more than 1.5 Celsius (C) above pre-industrial levels.

If landscape architecture is to be a vital part of the future, this report means that our work, which is now utterly dependent on fossil fuels, must change completely during a time when it will be needed more than ever.

Where things stand now

The planet has already warmed by 1C (approximately 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) and continues to increase. “Climate change is occurring earlier and more rapidly than expected. Even at the current level of 1C warming, it is painful,” says Johan Rockström, as quoted by The Guardian.

To stay below the 1.5C maximum tolerable temperature increase, global annual carbon dioxide emissions must drop by about half by 2030 and then be at essentially zero by 2050.

Basically, this report says that the world has 12 years to limit climate change catastrophe by rapidly weaning ourselves off fossil fuels

If we do not meet that goal, it is likely that global temperatures will continue to increase by at least 2C. That amount is considered the absolute outer boundary of civilization’s safe operating zone. To not cross that 2C boundary, we must completely stop burning fossil fuels not long after 2050. Thus there is no scenario in which we can continue to burn fossil fuels for much longer anyway.

But we do not want it to get that far. The UN report shows the immensely negative impacts of the difference between 1.5C and 2C warming.

With a 2C temperature increase, instead of 1.5C, sea level rise would affect millions more people. Ocean acidity and oxygen loss would cause 99% of coral reefs to disappear along with much needed food fisheries. Insects, vital for food production, are twice as likely to lose half their habitat at a 2C increase.

An increase to 2C would add more extremely hot days in summer, which would cause more forest fires and heat related deaths. Global population exposed to water stress could be 50% higher at 2C, and millions more people would be at risk of greater food scarcity and climate-related poverty.

Finally, an increase of 2C means that there is the possibility that large areas of permafrost will thaw, which would release more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, leading to runaway climate change which might not be survivable.

It should be frighteningly clear, then, that while a 1.5C increase is dangerous, the impacts of 2C or even higher global temperatures are absolutely terrifying.

People displaced by drought in Somalia arrive at the Dolo Ado camp in neighbouring Ethiopia and queue to be registered by the aid agencies running the camp. | Photo: DFID – UK Department for International Development

What it means for landscape architecture

To avoid that 2C future, the world needs “rapid and far-reaching” changes in energy systems, land use, city and industrial design, transportation and building use according to the report.

It is here that the report speaks to landscape architects. Those “rapid and far reaching” changes mean that within 12 years our profession must use 45% less fossil fuels than currently, and no fossil fuels at all within 30 years.

Landscape architects, like most professions and our whole society, are absolutely unprepared for this reality. For us, not being able to use fossil fuels will radically alter the materials and construction methods we take for granted. This in turn will have dramatic implications for design and professional practice.

For example, there will be little concrete and steel in a zero fossil fuel world, as they not only require fossil fuels for their creation, but their manufacture expels carbon dioxide. Ironically, this will also mean not being able to use those materials in efforts to adapt, say, to the effects of climate change. (Read more here)

Perhaps more importantly, building our projects without using fossil fuels will demand of us not only a new creativity, but also honesty and equity in how that is accomplished.

There appears to be little hope in technology scaling up fast enough to let us continue to burn fossil fuels without consequences. Nor is it likely that we can continue to use fossil fuels but attempt to offset them in some way by planting trees or geo-engineering, for example. This report shuts the door on wishful thinking.

It is possible, of course, that we as a profession will choose not to eliminate fossil fuels from our work. The argument might be that if the rest of the world does not, how can we?

However, if landscape architecture is to grow in relevance in the coming years, we cannot continue to be complicit in what is now unmistakably the destruction of the only ecosystem in which we can live. We must lead by example if we are to survive. To do that, it is urgent that landscape architects begin a discussion of what it will mean for us to be fossil fuel free.

—

Lead Image: The Rim Fire in the Stanislaus National Forest near in California began on Aug. 17, 2013 and is under investigation. The fire has consumed approximately 149, 780 acres and is 15% contained. U.S. Forest Service photo.

The Most Important Chart for the Future of Landscape Architecture

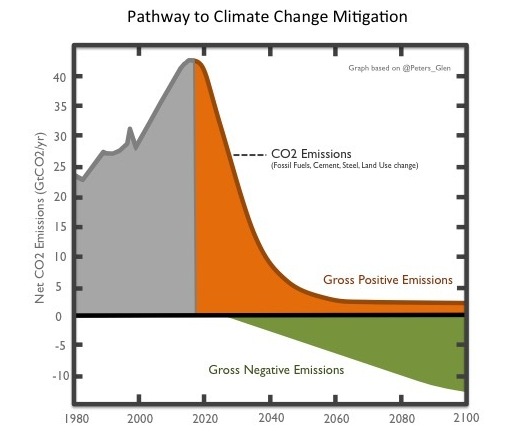

The chart above is of profound importance to landscape architecture as a profession and especially for any practitioner or student under the age of thirty.

This chart, which is based on the science supporting the Paris Climate Agreement, foretells that if we are to have any chance at salvaging a livable climate, humanity must essentially cease the use of fossil fuels within 30 years. Vitally too, this chart shows that we must work to draw down the excess carbon dioxide (CO2) that is already in the atmosphere. These two actions give us the best chance of bringing climate back into a balance conducive to civilization.

This “below zero” era of minimal carbon dioxide emissions and increasing CO2 drawdown will have enormous implications for landscape architects. For while the need for our work will only grow, eliminating the use of fossil fuels would radically alter the materials and construction methods we take for granted. This in turn would have dramatic implications for design and professional practice.

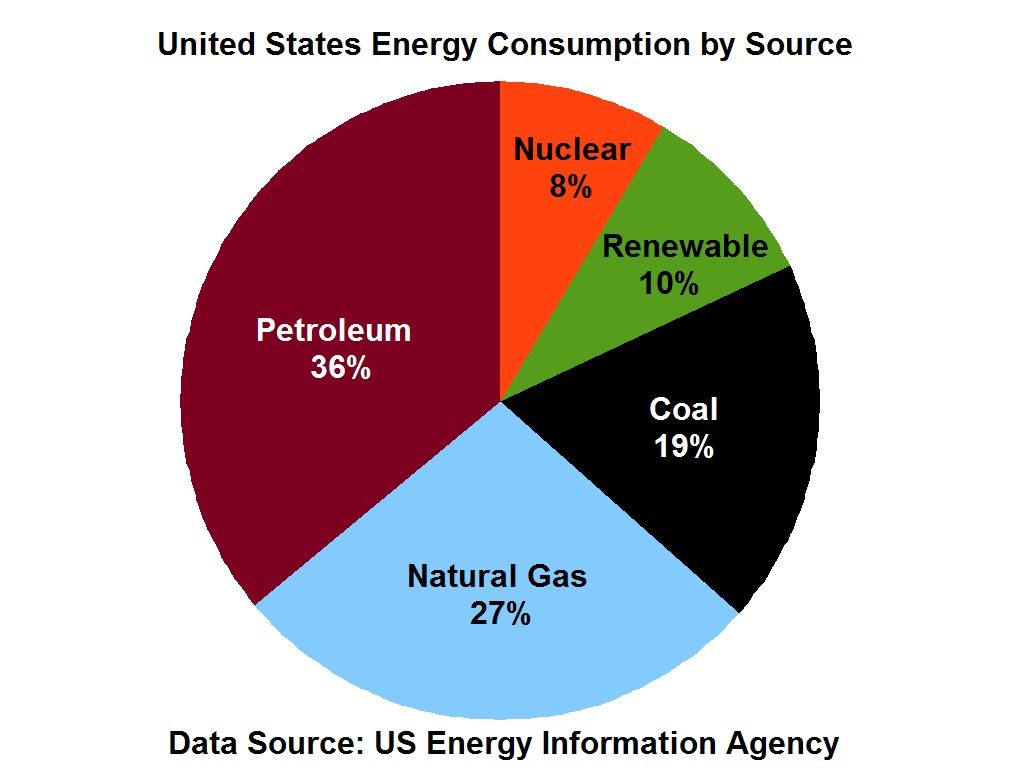

Fossil fuels provide 80% of the energy our society uses (see chart below).

Their elimination will immediately mean that society will have drastically less energy overall to use. At this point, many people will simply say, “yeah, but we’ll just use renewables.” Unfortunately, renewables are not a significant substitute for fossil fuels: they are not “plug and play.”

Renewables, which currently provide approximately 10% of our total energy supply, are at the mercy of the weather and the revolving earth. Even more importantly, renewables only provide electricity. But it is fossil fueled fire that powers our industrial civilization. It is fire that moves our large machinery and transports our supplies. It is fire that provides us with our most commonly used materials.

And yet this chart tells us that we must end the use of fire if we are to stop and reverse global warming. It is unknown, but seems unlikely, that renewably generated electricity alone can provide us with all the energy and materials that we have grown accustomed to.

For example, cement production is the third largest source of carbon dioxide pollution globally. It is literally impossible to make cement without emitting a large amount of CO2, as that gas is one of the byproducts of the production. Further, fossil fuels alone provide the heat required to expel that CO2. Thus, at the end of the process, as much as one ton of CO2 results from creating one ton of cement.

This is unacceptable in the below zero era. Remember, we can’t keep cheating; we must get to below net zero carbon dioxide emissions. Thus it is unlikely that landscape architects will be able to rely on using large amounts of concrete in their work.

Another example is steel production. Like the cement process, CO2 is a chemical by-product of the process of steel creation. To drive out that CO2 requires very high temperatures, normally supplied by fossil fuels, especially coke, which is a high carbon form of coal. While some quantities of steel can be made with electricity, there is no evidence that large-scale amounts of non-CO2 steel can be produced. Again therefore, large-scale use of steel may be unlikely.

In addition to cement and steel, other common materials that may be severely curtailed by ending the use of fossil fuels include most plastics and metals, fired bricks, ceramics, and glass. But it is doubtful that the need for the functions provided by those materials will decrease correspondingly.

Most construction equipment requires fossil fuels.

Construction methods will also be directly affected. Most landscape architectural projects involve fossil fueled machinery. Trucks, backhoes, skid steers, and earthmovers: all depend on fire. While it is possible to run some equipment on electricity, it is doubtful that we could count on the amount of energy and machinery we utilize today. Therefore, landscape architecture in the below zero era will have to look to other means to perform much of our necessary work.

These realities will deeply influence design. The design process, which now takes insufficient notice of embodied and required carbon in both materials and construction methods, will need to respond to a completely new paradigm. In the future, a principal way that design will be evaluated is by how much carbon it draws down. Designers will learn to work with different materials, including reused and repurposed ones, and find new ways of accomplishing the construction process. Design for maintenance without dependence on fossil fuels will be essential.

The below zero era will also greatly impact professional landscape architecture practice. Managers will need to respond to limits in practice scope compelled by changes in transportation modes. Landscape architects might need to become more directly involved with construction projects. Ethical considerations such as what types of projects to use limited energy on may become more important. Landscape architectural education will need to adjust to these realities as well.

Many will hope that these realities are overstated and that technology and other actions will enable business as usual. They will point to the possibilities of biofuels, carbon scrubbers, massive tree planting to offset emissions, and even geo-engineering as pathways along which we can continue as we have

Unfortunately, there is little evidence that any of those will enable us to continue to pour CO2 into the atmosphere without unimaginable consequences. We have gotten ourselves to a pretty stark place.

The world is on the edge of an epochal change, with two choices for moving forward. We can continue business as usual, accepting the ravages done to our life support system by climate change in the hope that somehow it will be survivable. Or we can voluntarily choose to eliminate fossil fuels and begin to craft a new economy and way of life on different kinds of, and much less, energy. If landscape architects are going to lead with authenticity, it is vital for us to become knowledgeable about the implications and possibilities of the below zero era.