Who wouldn’t want to live in this magical cottage in the Florida pine flatwoods? Cadence created this wonderful image – check their social media for the full story.

Landscape architecture as a discipline has a long and troubled history with images. The English word landscape, to start, originated in European painting tradition. Landscape architecture theorists and practitioners still argue over the role that images should play in our profession. So it’s perhaps unsurprising that the public introduction of generalist machine-learning image generators – such as Dall-E and Midjourney – in Spring 2023 was met with consternation in the profession.

Speculation over the following months has been hyperbolic. Will these tools free up landscape architects’ time and help us better communicate the futures we imagine? Or will they strip all the creative components out of our practice and automate the fun away? I spoke to designers from 4 different practices and practice types across the United States that have been experimenting with AI image generators. They’ve had a range of experiences – check out their work and see how it aligns with your own practice’s experiments.

If you follow #landscapearchitecture on Instagram, you’ve seen @pangeaexpress – the Instagram handle of Eric Arneson, who operates Topophyla – a southern California-based landscape architecture studio with Nahal Sobhati (read Nahal’s answers to 8 questions from 2021 here). Topophylla describe their practice as “analysis and process driven” and actively share their experiments with different tech tools and workflow techniques.

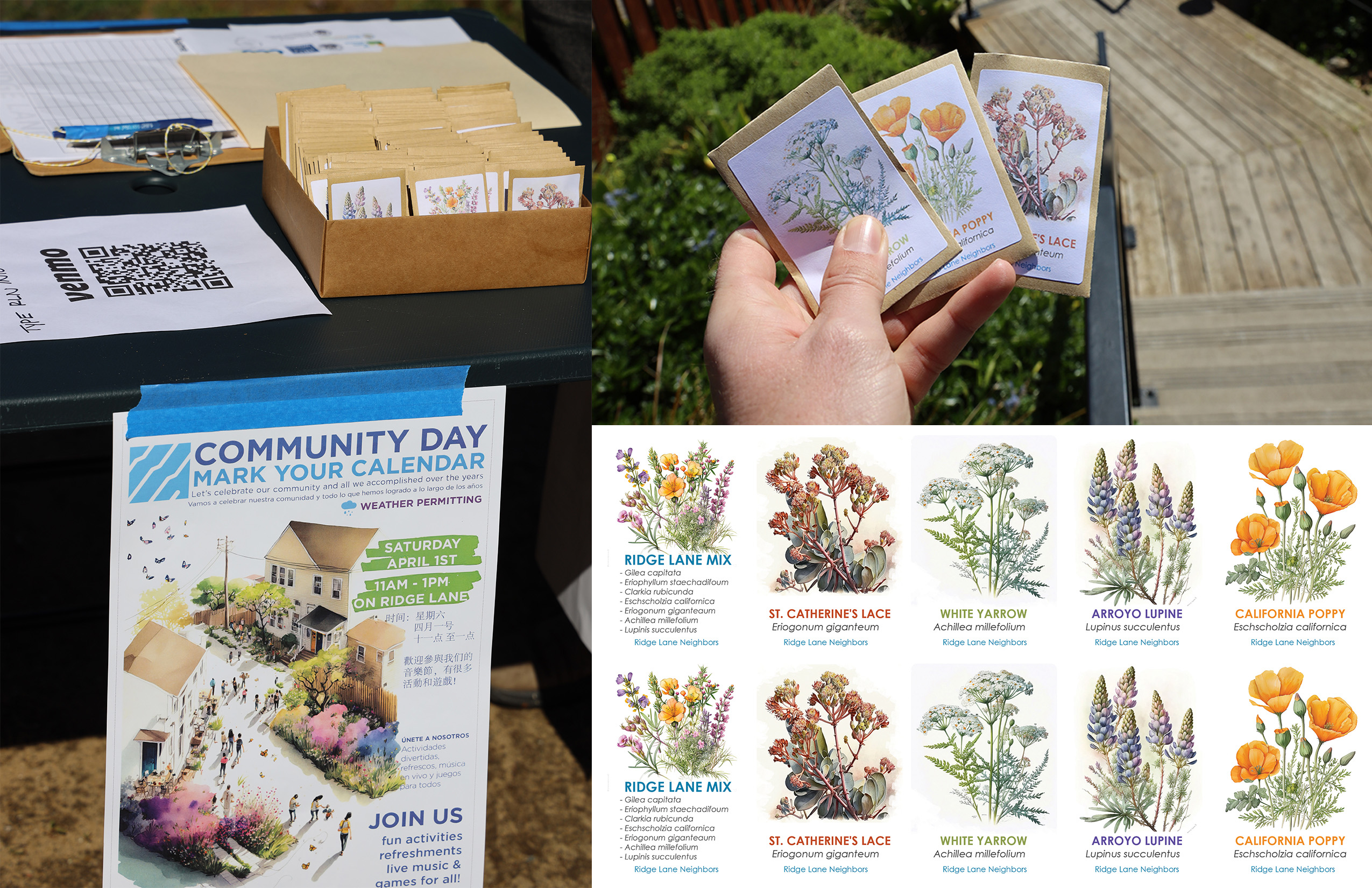

Topophylla use Midjourney at both the concept level – integrated with modeling and construction drawings – and to create vibrant illustrative bouquets showing the site materials and design vision.

Topophyla’s channels were one of the first places many landscape architects saw the future possibilities of AI image generation. Dall-E invited high-profile creators from a range of professions to play with the software and demonstrate the capability of AI image generation. “We got invited to the beta testing for Dall-E almost 2 years ago now,” Arneson says, “We tested it out with landscape architecture applications, seeing how it produced plant materials, how it laid out plans.” These days, Topophyla mostly use AI image generation for ideation, mood boards, and plant palettes.

While enthused about the possibility of using AI image generation to support practice, Arneson saw people commenting on images that – to him – were clearly AI generated and thinking they were photographs. “I wanted a platform to address the fact that not a lot of people know what AI is capable of,” Arneson says. To counteract misconceptions and help people recognize AI generated imagery, Topophyla have started a new Instagram account, @artificial_olmsted. Give it a follow to learn the latest “tells” for AI-generated imagery and stay up to date with new development affecting our profession.

Topophylla used Midjourney to create watercolor images for seed packets as part of a community garden project – making for a deeper level of engagement/excitement.

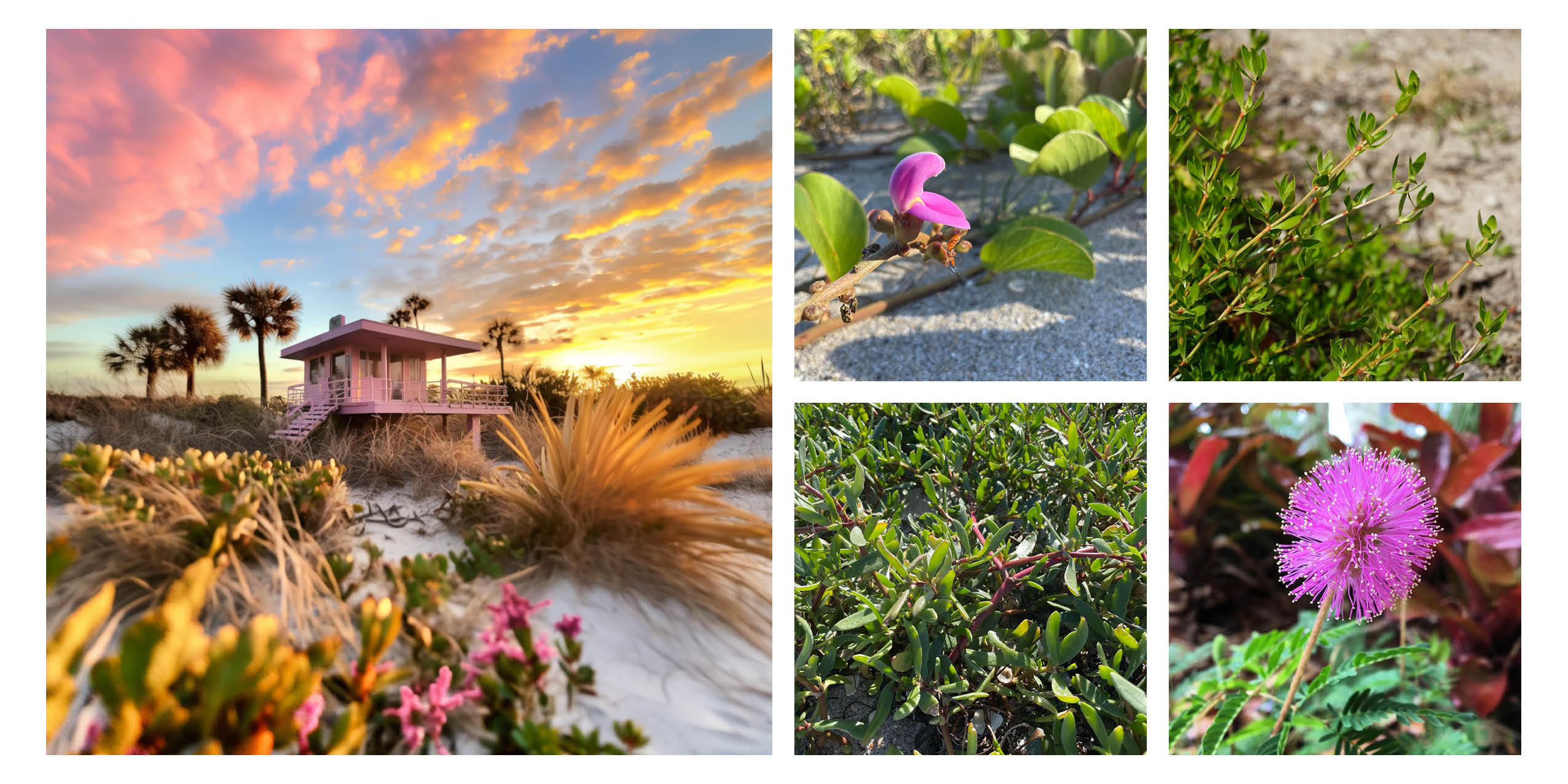

Florida design enthusiasts – especially those with a penchant for native plants – follow Cadence, a south-Florida based landscape architecture studio known for beautifully-crafted designs celebrating regional style and materials. I spoke with Stephanie Dunn, design associate, about some images the Cadence team created. “We got this thought, with the whole Barbie trend, should we play in this realm of imagination?” Dunn says. The Cadence team would usually start drawing something by hand or modeling, but for this social media experiment, Dunn used Midjourney to create a couple of images envisioning fantastic Florida landscapes with a bright pink color palette.

Cadence’s Fort Lauderdale design team started with plant lists for the dream scenes that they wanted to envision, and Dunn started plugging away with test prompts. For the first one, the Barbie beach house, Dunn notes that she was really learning the program and had quite a bit of trial and error up front. But, for the second image, depicting a cabin in the pine flatwoods – the overall composition she had in mind emerged as part of the second round of images. Dunn notes being struck by the “instant satisfaction of seeing something right away – versus a lot of what we do. You push a button, and 20 seconds later what was in my head has come out and this is amazing. It’s also, at the same time, a little startling, and slightly terrifying, but very cool.” Dunn and the Cadence team made sure that the images they produced using Midjourney accurately represented the plant species that they would use and built out social media posts using photographs of native plants to demonstrate what species could actually be used to create the kinds of environments shown in their images.

Cadence’s team has been deeply considering the potential role of AI image generation in their practice and workflow. “Our clients are hiring us because of the way we think,” Dunn says, “To us that’s highly valuable.” She notes the importance of accuracy in representing plants – something that’s been challenging with Midjourney, but can also be an issue with existing tools like Sketchup and Lumion. Dunn sees the Cadence team integrating these softwares if “AI could help us produce something quickly in order for us to have more time to devote to designing, if it could take away some of the menial things or analysis, but without taking away the thoughtfulness that we really care about.”

Cadence envisioned a fantastical beach cottage – and explained the Florida native plants that they’d use to actually create this landscape. Plant (starting upper left, clockwise): Baybean (Canavalia rosea), Beach Creeper (Ernodea littoralis), Sunshine Mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa), Pink Purslane (Portulaca pilosa). photos by Stephanie Dunn.

SmithGroup is an integrated design firm – engineering, architecture, landscape architecture, campus planning to name a few of the in-house disciplines – with 20 offices across the US and China. I spoke with landscape architect Brandon Woodle about how he and his team have been tested the use of AI image generation in their design process. “Our experiments with AI image generations were happening in a decentralized way,” Woodle says, “Different designers were messing around, mostly in their free time, exploring how it could influence their work and practice.”

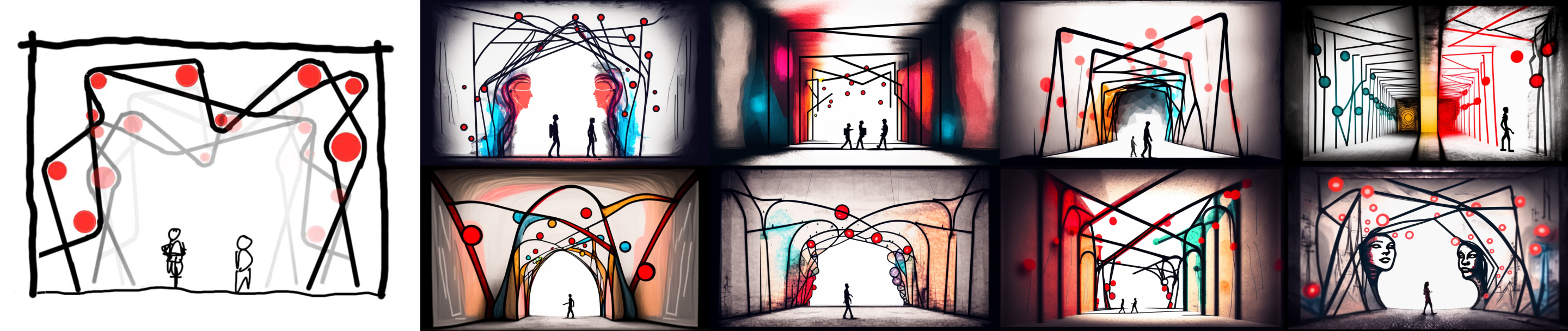

Woodle and his team were working through early concept stages of a project with highly specific conditions: an existing tunnel reimagined as a pedestrian and bicycle connection.The specificities of the project led Woodle to “try and use AI as a tool because it could craft the prompts in a way that would be applicable directly to this certain type of environment that’s not a typical park”. Woodle began with Midjourney and notes that it was interesting to see how prompts using basic terms around ways of shaping space and experience – such as repetition, light, enclosure – were interpreted by the AI image generator.

Woodle quickly found that, while Midjourney would generate many images quickly, the images were overall very similar to each other. He broke the monotonous results using a few different techniques. Woodle used ChatGPT to write prompts, which generated much more variable images than those generated by his earlier prompts. He also took rough hand sketches and combined them with text prompts. “That was an interesting way to iterate on my own sketches in a bunch of different ways,” Woodle says.

The generic quality of the images limited the usefulness of Midjourney for anything beyond concept imagery. “Even incorporating images of the tunnel itself, Midjourney takes liberties and abstracts a great deal,” Woodle says, “I didn’t get quite to the point where I could picture something in my head, describe it with a prompt, and get the image that was in my head. That’s where we kind of hit a wall with it.”

Brandon Woodle – landscape architect at SmithGroup – started with hand sketches (“Portal”, on the left) and worked with Midjourney to generate concept images for a pedestrian tunnel.

Curry Hackett is the founder of Wayside Studio (est 2015, currently based in Cambridge, MA) and a transdisciplinary designer with a background in architecture and urban design. He began experimenting with Midjourney in spring 2023 as part of a studio at Harvard GSD. Collage has long been part of Hackett’s practice – he uses it as a critical practice for challenging perceptions and relationships within images.

Starting with Midjourney to create components of collages and renderings, Hackett began exploring how “to use Midjourney as a way to bring that kind of collageness to a new way of making images. In a way, taking people, black people, and putting them in uncanny settings was a way of me thinking about – what can this do?” Hackett says, “How well does this, can this, program render blackness, black lives, black joy, black abundance?”

Hackett’s images often begin with a detail or joke that he explodes to create images of landscape and urban scale experiences. “I’m advocating for the visibility of southern blackness, also advocating for the inherent sophistication of what I call “the so-called mundane” as it pertains to everyday black life,” Hackett says. As an example, one of Hackett’s experiments into AI-generated video (using Runway) was grounded in his experience growing up in rural Virginia. “The bathtub series, people growing vegetables, that’s coming from a real trope of southern black traditional gardening, on the farmlandt, my great aunt and uncle as long as I can remember growing flowers and plants out of toilets and bathtubs and sinks.” Hackett played around with visualizing the concept using AI, speculating, “What if that customary – but also kind of obscure – trope was scaled up to be hypervisible and placed in a setting like Harlem?”

Hackett is the only practitioner I spoke to who mentioned regularly using Midjourney through Discord’s mobile app. “A lot of people are surprised – 98% of the images that I’m making online, I’m making lying in my bed,” he says, “Or I literally had a funny idea and sat at a coffeeshop and banged it out in like 15 minutes.” Hackett notes this ability to quickly iterate is part of the potency of AI image generation.

Hackett’s conceptually compelling and visually impactful images have drawn widespread social media attention. “When I started doing this work, I had about 3000 people following me on Instagram, mostly peers, family, and friends, but with a pretty heavy design/architecture bias,” Hackett says, “I’m really excited that this work is resonating with not only more people, but more people that are not big A architects or not in our discipline in a direct way – the following is much more coalitional. I’ve got people from the black hair care space following me, I’ve got people in black music space, black food space, black farming space, there’s this really cool cornucopia effect over the past 4-5 months that I might not have had with my existing organic growth.”

As his audience grew, especially through social media, “I was surprised by how disturbed some people were by images of what I thought were joy, that were clearly artificially made,” Hackett says, “For me it highlighted rightly that black folks are suspicious about how we show up in historical narratives, suspicious of how history is authored.” Hackett found that adjusting text descriptions to explicitly frame these images as speculations and AI-generated imagery shaped how people reacted to his work. For Hackett, this experience highlighted that “AI is necessarily going to be interacting with other disciplines. It is going to be embedded in how we consume media, how we write.”

Curry Hackett’s images investigate speculative pasts – and hopefully inspire a new generation of creators to build a more beautiful world.

If any profession claims a right to embed images in understanding of different fields, it’s landscape architecture. Our interdisciplinary profession is well accustomed to picking up tools and combining them with a generalist’s eye to picture the kinds of futures we want to bring to life. If landscape architects follow the example of the practitioners interviewed for this piece and put these tools to work for us, we could design and represent our ideas more effectively. Let’s do it.

FURTHER:

I’ve written this article from the perspective that people, at this point, would likely have a general understanding of how machine learning AI image generators work. If you’re unfamiliar with how AI image generators work, PBS has a useful article here.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured

David Cristiani

Excellent review, Caleb. Everything I wanted to ask you, and then some!

Caleb Melchior

Thank you, David! It was great to get to talk to all of these experts about their experiments.

Doug Davies

Love it- if you haven’t checked out SketchUp Diffusion, it’s worth a peek!