This piece is about using landscape architecture methods to explore community foodways, specifically in the Brazilian Caatinga ecoregion. My own upbringing in Brazil has imparted an admiration for the communities that make my country what it is today and the natural environment at the core of their identity. I am interested in mapping unique rural cuisine in an effort to show that food is a significant cultural element that ties people to native landscapes. There is a possibility to tell stories of social resiliency and environmental responsibility through traditions and landscapes.

Studying landscape architecture has allowed me to look at Brazil with newfound appreciation. During the last year of my graduate studies, I used my skills to relearn the history and heritage of the Northeastern region and communicate them to a wider audience that might not have heard of them otherwise. My focus was on the Caatinga, a xeric shrubland vegetation, known in the indigenous language of Tupi as “mata branca” or white forest. I knew that I lacked so much information about this ecoregion, even though I grew up much closer to it than the Amazon rainforest. Early on in the seminar course guided by Professor Linda Chamorro, I decided to focus on the two pieces that felt closest to home: community resiliency and food.

Since moving away from home, I can recall each visit to my grandparents with a fresh home-cooked meal that made it feel like I never left. I remember my godmother, Dona Eulina, who shared her love through cooking. Something that always seemed simultaneously simple and complicated. Since I personally didn’t grow up on a farm or become a great cook, I didn’t think that I would share that connection to the environment as my grandparents and godmother. However, I learned early that the food we eat everyday reconnects us to a product of the soil. I learned that my grandparents cherish the landscapes for its unique resources, such as certain species of edible plants endemic to the Caatinga eco-region. During my graduate studies, I wondered if landscape architects could extend their role as communicators to agrarian communities at risk of environmental disaster and reconnect the conversation of ecological restoration and culinary traditions. Landscape architects have a great role in protecting homes, habitats, and soil. I believe foodscapes are the key to design public spaces that support local efforts of reconnection to the landscape.

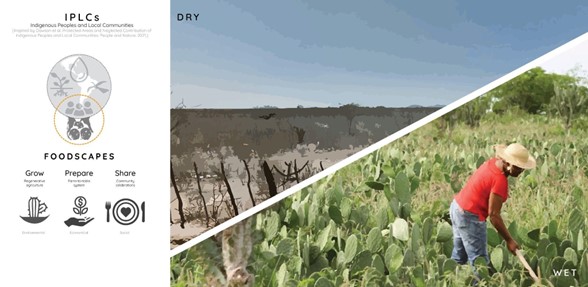

The Caatinga, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, is predominately a xeric shrubland. The IPLC’s knowledge of foodscapes is an invaluable resource for the understanding of these hyperlocal ecologies.

The name “Caatinga” is a Tupi-Guarani word and translates to “mata branca” or white forest. As a seasonally dry xeric shrubland, the Caatinga is a lesser-known ecoregion of South America, but it is symbolic to the culture of Northeastern Brazil. With just enough rain, this dry vegetation can transform into a green landscape. The communities that live there know this and cherish the land for its subtle beauty. The practice of regenerative agriculture has been around longer than the term was coined and practiced by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. In Eating the Landscape, the ethnobotanist Enrique Salmon describes IPLC’s as caretakers of the land and we have the task of relearning how to cook our landscapes. This is the concept of foodscapes. The creation of spaces where we can grow our food, prepare it by strengthening local economies, and sharing food in our celebrations.

While common stereotypes question the need for preservation of this tropical dry forest, I have learned to appreciate the resiliency strategies of both plants and people in this area. The remote rural communities have generational knowledge of farming, grazing, and selective harvesting, including plants with the capacity to hold water like the umbu tree. The cycle of deforestation, prolonged droughts, and exacerbated poverty increases harmful grazing practices and risks the livelihood of these communities. Simultaneously, this threatens the food traditions unique to the region as people are forced to move to larger cities for better living conditions.

Global mapping of agrarian communities cited by Nabhan Gary in Growing Food in a Hotter, Drier Land

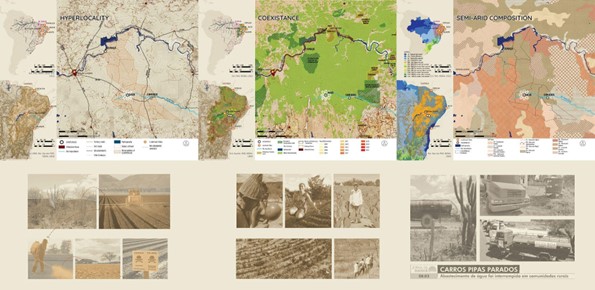

How can a symbiotic relationship between agriculture and arid landscapes help strengthen resilience in vulnerable communities? As desertification and climate change affect biodiversity and soil health in arid landscapes, this presents an opportunity to apply this thesis question to the field of landscape architecture. My initial mapping of these globally distinct and hyperlocal communities was based on the findings by Nabhan Gary as he explains in his book, Growing Food in a Hotter, Drier Land. This map is a continuous project, but, as it is now, it demonstrates the global importance of learning from hyperlocal communities in analogous contexts. I believe that landscape architects, wherever they may reside, can benefit from studying the long-term resilience of agrarian communities. The project’s research began on collecting information of global small-scale agricultural communities and honed in on the Brazilian Caatinga ecoregion.

National, regional, and local mapping of the Caatinga ecoregion and the project site within the Sertão do São Francisco.

The project site is in the heart of the Sertão do São Francisco, in North Bahia, in a city called Uauá. This city combined with its two neighbors has become regionally known as the Cooperativa Canudos, Uauá, e Curaça (COOPERCUC). Nested in the heart of the Caatinga, the area of Uauá is only accessed by a federal highway. Like many other remote towns in this region, lack of access to water creates a dependence on water trucks.

While the city of Uauá is relatively young, the COOPERCUC began in 1986, when 20 women in Uauá noticed that the umbu, a local fruit used in traditional recipes, was disappearing. They led a community initiative to preserve and nurture the remaining trees. Today, the COOPERCUC provides a network of small farmers, sharing knowledge and making products from ethnobotanical plants.

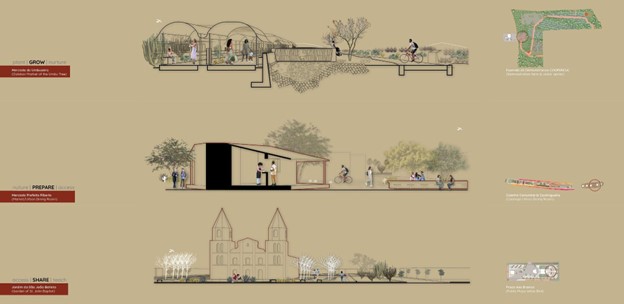

The existing efforts to support the local biodiversity and economy through a ground-up approach have created the foundation of the project; upon this, the design intent was to support, enhance, and celebrate the foodscapes within the city of Uaua. The programming needed to be focused around the original concept of spaces to grow, prepare, and share food. GROW was introduced through demonstration farms serving to produce crops and educate the general public on the process of regenerative farming. PREPARE was focused on the social interactions behind cooking and exchanging recipes, thus becoming an opportunity to revitalize an existing linear park into a native garden and urban dining room to attract local farmer markets. SHARE, the last ingredient, calls for the interpersonal reflection of community values, one where native vegetation in public places serve to cherish the peculiarities of living in a seasonally-dry landscape, amplify social awareness, and protect endemic species.

The proposed site plan highlights existing public assets and incorporates three of them into the proposal. The proposal creates three demonstration farms on the outskirts of the city core and moves inward toward the park and church. Each site is connected to an Agro-circuit, aiming to guide residents and visitors through Uauá.

Landscape architects have the capacity to engage social awareness in each typology of foodscapes; grow, prepare, and share.

In the demonstration farm, visitors can walk through examples of local traditions and experimental techniques in water harvesting. Along the way, open-air pavilions serve to tell the histories of IPLCs, and visitors can learn of the subtle miracles behind this seasonally dry forest in before and after rain.

An existing linear park serves as a central node within the Agro-circuit. In order to celebrate the artistic nature of the residents, areas for community art projects bring new life to the space. In a family kitchen, seniors share recipe secrets with the younger relatives. In similar fashion, the proposed Urban Dining Room serves as a space to Prepare food as a community. As a commercial point for temporary markets, the space regains life every weekend in time for lunch.

The last stop is the space for celebration, hosted in the central church and plaza. The proposal aims to bring the Caatinga vegetation and symbols to this space as an opportunity to teach the culturally accumulated ecological knowledge, through a medicinal garden and a new surrounding for the outdoor stage. Within each typology of public space, the spatial experience allows for a slower pace in the landscapes that change in dry and rainy seasons, allowing for a subtle understanding of Uauá just as part of the Caatinga as the Caatinga is part of it.

Foodscapes set the stage on how landscape architects can support agrarian communities living in arid landscapes.

Landscape architects can understand agricultural communities and arid landscapes to protect livelihoods that grow, prepare, and share food. And foodscapes can become a catalyst for ecological and social infrastructure. As an aspiring landscape architect, I value the opportunity to think beyond the limits of a site, and bring the needs, wants, and aspirations of a community into the design process. My graduate studies in landscape architecture have allowed me to look at Brazil with newfound appreciation. During the last year of my graduate studies, I used my skills to relearn the history and heritage of this region and communicate them to a wider audience that might not have heard of them otherwise.

Perhaps, as communicators of environmental design, landscape architects can also play a role in documenting and sharing stories of local traditional cuisine that use ingredients from the resilient native vegetation, such as that of Sertão do São Francisco. Innumerable platforms and media serving both printed and digital formats can assist local initiatives, such as school lunch programs, to keep food traditions alive. In the end, I hope, these efforts can also serve to reconnect younger generations and the diaspora to their heritage and employ generational knowledge to improve resiliency in the communities that need it most.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured