Author: Land8: Landscape Architects Network

Mo I Rana Waterfront Competition Winners!

Arkitektgruppen Cubus AS, a Norwegian office from Bergen have won a competition for a waterfront in Mo i Rana in the north of Norway. The concept: maintaining the identity of an area, but at the same time infusing it with a new pulse by carefully placing recognizable and innovative spatial elements in strategic places. Over time the transformed hotspots will start working as a continuum, offering a wide range of activities for leisure, play and inspiration. This is the main idea behind the project for the Norwegian city of Mo I Rana. The project took place on the fjord coastline bordering the town’s densely built up space, with a view to the magnificent natural landscape around.

The module-based design of the seafront promenade facilitates it for new recreational activities. The seafront promenade will be retained as a mainly natural landscape with indigenous flora and fauna. The area closer inland bordering the housing belt will be developed to a higher degree of cultivation with a park-like character with flowering plants forming the border to the gardens. The southernmost area will be laid out with trees, lawns, paths and lighting- a general green park for strolling and play. Mo I Rana’s economy has rested mainly on the industrial processing of steel and concrete. These industries have been of major importance for the growth and identity of the region as a whole, and have had a dominating influence on the built seafront, since this is where the factories lie. The spatial modules are aimed to be produced in the local industrial factories rather than imposing design strategies and materials from elsewhere. The proposal involves the design of a series of large scale spatial modules, used to transform the local terrain and microclimate to provide places for shelter, sitting, reclining, access, connection between levels, play and sport, as well as evoke curiosity. By allowing local knowledge and technology to be a design parameter, the project will be deeply rooted in the local identity and an expression of the pride and capability of the local community. It also allows for innovation in local industry by establishing a new production line for use in the seafront project. The designers’ main purpose is to strengthen the sense of identity and pride in the project through the use of traditional technology and innovative design and perhaps inspire a new wave of regeneration for both the industry and the town. The modules are used to enhance and highlight nature along the coast which also contrast with extraordinary places like the skating area. It is a path going above the fjord and also a place for brave skaters. Below: Slides of the modular components in the design.The seafront will tell the story of a strong, intertwined industrial community of which it is a part. Project name: Competition for Mo I Rana Waterfront (1st place) Location: Mo I Rana, Norway Company: Arkitektgruppen Cubus AS (Bergen, Norway) Consultants: Graphics Design: Truls Indrearne – Haltenbanken, 3D illustrations: Fabian Gohde – Studio Gohde Report by Slavyana Popcheva

Top 10 Pedestrian Bridges

Pedestrian bridges — or footbridges — are structures that link two distinct areas, providing access for pedestrians (and, in some cases, cyclists). In a world that is mostly vehicle-oriented, these elements are a great way to facilitate motion in the chaotic urban environment, where increasing traffic is a relevant issue. In terms of function, footbridges must provide safe and easy access across streams, roads, railroads, and so on. Although they are built more to a human scale (compared to highways and vehicular bridges), pedestrian bridges still make a big visual impact on the landscape, so aesthetics is very important to ensure that this impact is positive. With that in mind, designers have turned these elements into real works of art — check out our Top 10, featuring the most incredible examples from around the world: 10. The Rolling Bridge (2004) – London, UK It looks like an ordinary steel footbridge at first, until it curls up like a caterpillar! Designed by Thomas Heatherwick, this bridge at Paddington Basin allows the passage of boats — when up — and the crossing of pedestrians — when down — due to the hydraulic system that powers the structure. To see it working, check out this video: 9. Moses Bridge (2010) – Halsteren, Netherlands Moses Bridge is not its official name, but one can easily guess why it is called this. At first glance, pedestrians seem to be walking through water, just like in the biblical narrative in which Moses crosses the Red Sea. Designed by RO&AD architects, this “invisible” bridge was built under a moat’s waterline on a 17th-century fortress and its entirely made of wood waterproofed with foil. 8. Arganzuela Footbridge (2010) – Madrid, Spain

Arganzuela Bridge in Madrid Rio Park, Madrid, Spain. Designed by Dominique Perrault, it is 274 meters in length and formed by two spiral-shaped walkways; credit: prochasson frederic / shutterstock.com

BP Pedestrian Bridge in millennium park, Chicago. The bridge spans Columbus Drive to connect Daley Bicentennial Plaza with Millennium Park, Designed by Frank Gehry; credit: Richard Cavalleri / shutterstock.com

Top 10 Names in Planting Design

If you are into plant design, nature, and/or landscape architecture, chances are that coating the world in vigorous greenery is up there on your to-do list. However, sometimes doing so isn’t as easy as it seems, because without sufficient planting-design expertise, sooner or later you are bound to blunder. The following 10 names are professionals possessing authentic horticultural and planting flair, so take note. 10. Paul Thompson

Excellent display of a rich planting scheme; credit: Paul Thompson

9. Noel Kingsbury

Planting in the famous Highline project; credit: Stuart Monk / Shutterstock.com

A gardener since childhood, Kingsbury is also a plantsman, writer, researcher, teacher, and innovator. He is best known for his naturalistic approach to planting design, and is an advocate of the new way of using perennials that work with, rather than against, nature. He has written a plethora of books on garden matters, including a history of plant breeding, and has collaborated on several books with leading garden designer Piet Oudolf.

Recommended reading: Planting: A New Perspective by Noel Kingsbury

8. Thomas Rainer

An incredible display of texture and colour; credit: Thomas Rainer

Washington-based landscape architect, teacher, and writer Thomas Rainer is a proponent for design aesthetics that interpret nature, rather than imitate it. Predominately using a native palette of grasses and perennials, his most notable work around America include the U.S. Capitol grounds, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, and The New York Botanical Gardens.

Check out his blog Grounded Design

7. Tom Stuart-Smith

Stuart-Smith is a British landscape architect whose planting designs are highly reputed for seamlessly integrating naturalism with modernity. To date, he has garnered eight gold medals at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show. Perhaps his most widely recognized work is that of the Jubilee Garden at Windsor Castle, seen by more than a million visitors every year. Recommended reading: The Barn Garden: Making a Place by Tom Stuart-Smith

6. Patrick Blanc

An incredible green wall display; credit: Patrick Blanc

Known worldwide for inventing the concept of le mur vegetal, the French botanist and designer deservedly makes the list. Blanc works as a researcher with the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris, and from the age of 12 has been getting his hands dirty experimenting with ways to propagate plants sans soil and light.

Recommended reading: The Vertical Garden: From Nature to the City by Partick Blanc

5. Kongjian Yu

Shengyang Jianzhu University campus; credit: Kongjian Yu

Yu is the founder of prolific Chinese design group Turenscape, whose work often focuses on adapting to flood and environmental crises. He abhors China’s urban elite ornamental landscaping, instead expounding the benefits of China’s traditional peasant aesthetic, using agriculture and productive rural landscapes to obtain survival and productivity.

Recommended reading: Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu by William Saunders

4. Nigel Dunnett

Professor Nigel Dunnett work revolves around creating dynamic and ecologically functional landscapes, and was the mastermind behind the intensely hued wildflower meadows surrounding London’s Olympic Park. He is an advocate and expert on green roofs, pictorial meadows and water sensitive urban design, and has authored several books on the subjects.

Mixed boarder used to great effect; credit: Nigell Dunnett

Mixed boarder used to great effect; credit: Nigell Dunnett

Recommended reading: Planting Green Roofs and Living Walls by Nigel Dunnett

3. Beth Chatto

Beth Chatto has been Britain’s most influential gardener of the last half-century, and is considered a British national treasure. Remarkably, Chatto received no formal horticultural training, instead amassing extensive knowledge of plant ecology through her late husband. She has authored many marvelously written books and works on the principle that plants grow best when placed in conditions closest to their natural habitats.

Recommended reading: Drought Resistant Planting by Beth Chatto

2. Piet Oudolf

The Dutch master plantsman, landscape designer, and author pioneered the titular “New Perennial” movement that combines perennials with ornamental grasses, and is perhaps now most famous for his intermingled slice of nature on the High Line in New York City. He has an inherit understanding of how plants behave over time, with his work striking an impeccable balance between control and no control. Recommended reading: Landscapes in Landscapes by Piet Oudolf

1. Gilles Clément

PARIS, FRANCE – Quai Branly Museum. The green wall on part of the exterior of the museum was designed and planted by Gilles Clement and Patrick Blanc, in Paris, credit: vvoe / shutterstock.com

Frenchman Gilles Clément is a horticultural engineer, landscape architect, gardener, botanist, and writer. His most influential work internationally has perhaps been his part of the Parc André-Citroën. For several years running, Clément refused the French national prize for landscape architecture, insisting it should be given to the real architects of the landscape — the anonymous French farmers, engineers, and foresters.

Recommended reading: Planetary Gardens by Alessandro Rocca

In the past, there has been a good deal of wrangling over how important plant knowledge is to the profession, with claims that many landscape architects are regressing in plant prowess. With such an array of vital skills needed in landscape architecture, it can be difficult to decipher whether or not an area such as plants necessitates further learning. If you wish to follow in the footsteps of any of the aforementioned names, you need to make plants your number one stock-in-trade.

The pursuit of knowledge is a lifelong journey, and I feel that like plantlife and your proficiency on the subject should be cultivated, nurtured, and grown over time.

Article by Paul McAtomney

10 Great Apps for Landscape Architects – Part 2

The second edition to our hit article featuring apps. to make your life as a landscape architect easier. We are spoiled for choice when it comes to apps — they range anywhere from recording our sleep cycle to reminding us to brush our teeth. Apps are constantly being developed to make our lives more interesting, if not easier. The apps for architecture and landscape architecture are plentiful, adapted to our habits from desk to field research and everything in between. In this article, I hope to show you some apps that made my academic life a bit easier and provided a more fascinating and different approach to projects.

Apps for landscape architects

1. Photosynth Photosynth stiches together numerous images of an area and puts it into one file, creating a panoramic picture. The app takes the images from left to right, up to down, to create a photographic orb. On field trips, I found this app very useful for recording the space in order to get a better feel for it when I returned for desk study. 2. Behance and Behance Creative Portfolio Behance is a site to display and discover online portfolios from across the artistic board, from categories such as Photography, Graphic Design, and, of course, Architecture. There are two apps, both by Behance: The first app is the site; the second is Creative Portfolio, which allows students and professionals to upload to the site, showcasing their portfolios. 3. Mini Scanner This app has saved me many a time in the library! It is a simple app in which you can “scan” text or pictures and turn them into simple black and white drawings that are clear to read. The app is free, but you can upgrade it and gain the ability to email your images. I found this app very useful when I had small paragraphs of text to use, but didn’t want to waste paper photocopying. This is a definite favorite of mine. 4. Virtual Sketchpads-Paper by 53 and SketchBook by Autodesk These apps are virtual sketchpads, designed to replicate a paper sketchpad. Both apps have an ease of options, allowing natural flow of the virtual pencil or pen. I find it works well even on the iPhone, but I would recommend a stylus. Paper by 53 is solely for iPad. 5. iRhino 3D This app allows you to interact with your 3D models made through Rhino 3D from your portable device. There are some constraints, as you must shade your model in Rhino before opening it in the app, and there is a file size limit of about 50MB. Related Articles:

- Top 10 Hints & Tips For SketchUp

- 10 AutoCAD Hacks for Beginners!

- 10 Great Apps for Landscape Architects – Part 1

6. Google Drive/SkyDrive In relation to your choice of email, these apps allow easy sharing of work and a peaceful mind. Whether it is my hard drive breaking down or, in a more recent situation, sending files that I couldn’t send through normal email due to size constraints — i.e portfolios, these are unbelievably useful. I have gotten into the habit of saving all my projects onto Google Drive after crits, and it really gives me peace of mind. 7. Adobe Reader Adobe Reader is a simple and familiar app that allows interaction across various platforms. You can open documents directly as they are sent. It is very user friendly, with easy functions, and allows easy input and editing of existing information. 8. Dirr’s Shrub and Tree Finder This app is a pocket version of the renowned Dirr’s book. Although this app is quite pricey, it seems like a very comprehensive app, with a variety of search options. This app is more for reference than plant identification, but allows a large, helpful book to be condensed into an application on your phone. 9. Evernote This app makes life in general easier! Although this is not a landscape-orientated app, we all need a bit of organization, and this app is here to help. It allows you to save, sync, and share files and, with an upgrade, you can take your notes offline. 10. Bluebeam Revu The perfect app for PDF creation, markup, editing, and collaboration for a paperless workflow. Also, ideal for punch lists and simple to navigate. Apps are becoming increasingly popular in the world of design, and certainly are certainly going to continue to influence the design process. With hundreds to choose from, and new creations daily, the future of apps for designers is bright! Recommended Reading:

- SketchUp 2014 For Dummies by Aidan Chopra

- The Complete Guide to Blender Graphics, Second Edition: Computer Modeling and Animation by John M. Blain

Article by Lisa Tierney Return to Homepage Featured image credit Syda Productions / shutterstock.com

Meadows by Design by John Greenlee| Book Review

In today’s world, a luscious, smooth, green carpet of a lawn in every garden is a given. No one seems to think or care about the strain that such high-maintenance greenery puts on the environment. The necessary water, herbicides and pesticides, the exhaust fumes of the machinery used to cut it — it is all an enormous burden we put on the surrounding natural environment. Fortunately, we have a choice — and John Greenlee proposes an excellent solution in his book “Meadows by Design”. Overview

The author of “Meadows by Design” is so enthusiastic and knowledgeable about the subject that it makes the reader want to go out and tear down their lawn right away. Greenlee’s passion for meadows shines through every page of the book. He answers all the main questions you might ask. Why is a meadow a great alternative to a lawn? How to do you establish a sustainable meadow? Which plants to should you choose? How to do you maintain it successfully? The author starts by explaining the meadow’s advantages, writes about the rules of design, and proceeds to include an extensive list of the best meadow plants. The reader is led skilfully through the incredible world of grasses and introduced to the best garden meadows around. All this is beautifully illustrated by the acclaimed garden photographer Saxon Holt. The meadows in the book are shown as incredibly rich ecosystems, safe and friendly spaces for pets and children, and a desirable part of every garden. Get it here!8 Amazing Facts About Trees That You Didn’t Know

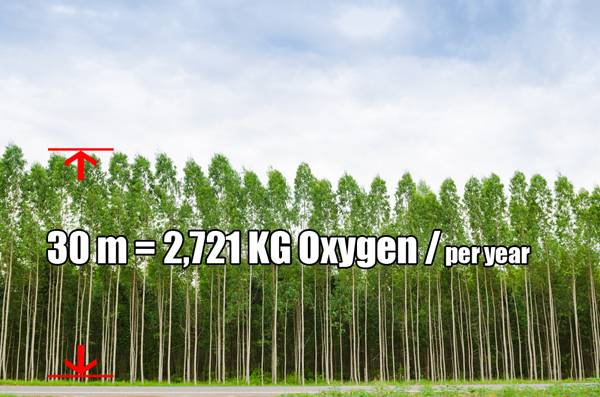

Here at LAN, we love trees. Just check out our hit article Top 10 Sacred Tree which highlights some of the wolrds most special tress in all of their awesomeness. The benefits of trees are widely known, but there are some amazing facts about trees that you might not know and will surely blow you mind! 8. A balance of carbon and oxygen A single 30-meter-tall mature tree can absorb as much as 22.7 kilograms (50 pounds) of carbon dioxide in a year, which over it’s lifetime is approximately the same amount as would be produced by an average car being driven 41,500 kilometers (25,787 miles). The same tree could also produce 2,721 kilograms (5,998.78 pounds) of oxygen in a year, which is enough to support at least two people. According to the University of Melbourne, because trees grow faster the older they get, their capacity for photosynthesis and carbon sequestration increases as they age.

Eucalyptus tree forest in Thailand; credit: Wuttichok Painichiwarapun / shutterstock.com. modification by SDR

7. Trees and wildlife

You probably knew that trees were good for wildlife, but did you know just how good? For example, the common English Oak (Quercus robur) can support hundreds of different species, including 284 species of insect and 324 taxa (species, sub-species, and varieties) of lichens living directly on the tree. These in turn provide food for numerous birds and small mammals. The acorns of oak trees (which don’t usually appear until the tree is around 40 years old) are food for dozens of species, including wild boar (and now more commonly pigs), jays, pigeons, pheasants, ducks, squirrels, mice, badgers, and deer.

The Oak tree is a home for many, don’t you forget it; image credit: shutterstock.com. modification by SDR

6. Who needs a compass?

When lost, it is possible to use trees to assist you in navigation. In northern temperate climates, moss will grow on the northern side of the tree trunk, where it is shadier. Failing that, if you find a tree that has been cut down, you can observe the rings of the tree to discover which direction north is. In the northern hemisphere, the rings of growth in a tree trunk are slightly thicker on the southern side, which receives more light. The converse is true in the southern hemisphere.

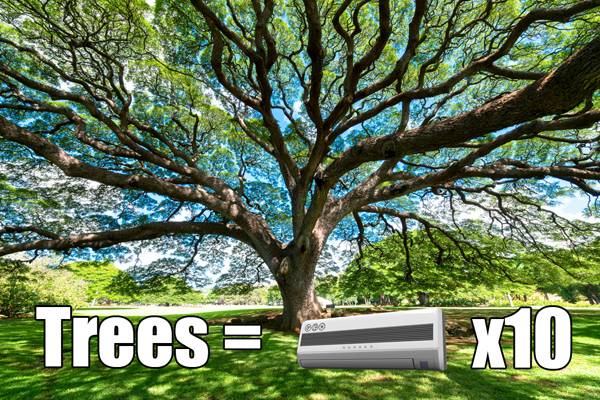

5. Saving energy and money Most people know that trees near buildings can raise property prices by an average of 14 percent in the U.K. and as much as up to 37 percent in the U.S. But trees can also have an impact on the energy used for heating and cooling a building, reducing air conditioning costs by as much as 30 percent and saving 20 to 50 percent on energy for heating. This is because as well as providing shade, a large tree can also transpire as much as 378.5 liters (100 gallons) of water into the air per day. This has a cooling effect roughly equivalent to 10 single room-sized air conditioning units operating 20 hours a day!4. Did trees really kill the dinosaurs?

There is a theory that the evolution of tall, woody, flowering trees (angiosperms) might have played a pivotal role in the extinction of the dinosaurs. It is believed, by some, that the speed at which flowering plants evolved on Earth (possibly spurred on by rapid climate change) occurred too quickly for dinosaurs to adapt their diets. Flowering plants are better at producing oxygen. With the rapid increase in flowering plants, scientists suggest that the metabolism of large herbivorous dinosaurs might have increased to the point that they could not eat enough food to sustain their increased metabolism. 3. Self-defense and communication Trees are masters of both self-defense and communication. Scientists have found that when attacked by insects, trees can flood their leaves with chemicals called phenolics. These noxious compounds are distasteful to tree pests and can even impede their growth. What’s amazing is that once a tree is attacked, it will “signal” to other nearby trees to also start their self-defense, before they are attacked! Methods of communication include releasing chemicals into the wind and possibly even sending chemical or electric signals through the michorizal network of roots (a network of shared fungus fibers).

Chemical signals are sent out to warn the other trees; credit: tr3gin / shutterstock.com, modification by SDR

There are many interesting facts about trees. You probably know most of the more common facts, but did you know about tree communication or about the oldest living tree on Earth? If you know of any more amazing facts we might have missed, please let us know in the comments below.

Article written by Ashley Penn Featured image: tr3gin / shutterstock.com

10 Tips Every New Landscape Architecture Professional Needs To Know

Landscape architect Brodie McAllister gives us his thoughts on what new landscape architecture professionals need to know in the first years of their career: At university, you have to balance deadlines for design and written work with a social life and the pressures of funding your place. You are challenged to let your imagination “fly” then pulled back to Earth with the consideration of practical details. This, to an extent, prepares you for the workplace after you graduate. However, nothing prepares you for work quite like “work”. What should you know or do, beyond what tutors have probably told you, to succeed in those first couple of years? It can be a bit of a hard landing when you finally get a job — there may be initial feelings of elation as you are released into the “real world” and a sense of independence. But in time, reality can “kick in” if your expectations are unrealistic. I want to offer some candid advice from my own experience, with a couple of anecdotes thrown in, so it isn’t necessarily beholden to some official line. 1. This isn’t boot camp

Remember, your job isn’t a continuation of college, and the employer doesn’t owe you training. This is business. Most employers will have a sense of responsibility toward mentoring you and guiding you to the experience you need to pass professional exams (e.g. Chartership in the U.K.). However, they are not obliged to — and some donʼt. Be the type of employee you would employ if it were your business — because the deadlines and time sheets are about money now, too, not just ideas. Itʼs expensive running an office, and the business owner is the one taking the main risks. 2. Be a sponge Learn as much technically/contractually as you can and get broad experience as soon as possible so you can branch out and do your own thing, if that’s what you want. You will make mistakes, so learn from them. For example, you may struggle toward some project deadlines or to reach or understand the presentation standards required. Donʼt worry. Keep working hard in an organized way and show keenness to learn new skills and acquire new knowledge. The best comeback from a mistake is to go on to impress them. Use those first couple of years to find out what might be your preferred area of specialization, and keep working toward that. For some, there is nothing more liberating and satisfying than eventually being your own boss. You can take all the credit! 3. Pack your bags, we’re off Always grab the chance to work abroad. When I graduated, it was the start of a world recession. I thought that it would be better to suffer the recession abroad, while getting a great life experience. I chose New York and then San Francisco because, through reading magazines, I had admired what the profession did there. It was not easy working in difficult times, classified as a “temporary alien”, but I had a terrific four years and got some extraordinary experience, meeting wonderful people along the way. The work we do can be international, and the experience you gain can give you the perspective you need to pursue that. Who knows, you may like it so much you stay. 4. Take off the rose-tinted glasses Don’t always expect to do the fun, creative design work in the early stages of training. This depends on which country you are in. My experience in the U.K. as a young graduate was that I did get the responsibility of the conceptual design work on huge projects. I thrived on it. But then there was a depressing bump when I was asked to do drafting of what I perceived to be boring standard details again. In America, they tend to be more structured and give conceptual design the top priority, to be done by the most experienced staff. This explains why we still import and revere their designers more than they do ours, although Europe has become more advanced in the last two decades in terms of opportunities to complete exciting projects. For many graduates, though, their raised expectation of being given this responsibility may lead to the biggest disappointment they will endure. Instead, refer to my point 2 above: Itʼs the bedrock of good design, and good design flows into the technical implementation. 5. Face the fear of leaving Remember: If you find you are not suited to this job or to a certain way of working as a landscape architect, try something else. Transfer your skills. This may be necessary if you are in a recession and finding it hard to get a job. Donʼt feel morally obliged to stick to what youʼve been trained to do. Itʼs your life. Landscape architecture is supposed to be a vocational profession, but therein lies a little professional conditioning that tries to keep hold of you. Landscape architects are well set up to follow other career paths, such as art, film, the contractor or commercial side of landscape products, or anything environmental. Even if you need to get further experience or qualifications, if you are “flogging a dead horse”, make the change now. 6. Don’t go chasing waterfalls Getting good experience is often worth more than working for a “famous” office. When I taught at university, Iʼd always hear students express their desire to work for one of the “big glam” names. After all, that is where they believed they would have the most fun on the most prestigious projects. Their experience, in hindsight, didnʼt always match this expectation. Worst-case scenario, they would be used as CAD slaves fueling the projects of ego-laden bosses. 7. Learn to survive Surviving in the first few years is often more about getting along with people and meeting deadlines. As I got frustrated at times that I wasnʼt getting what I wanted work wise. I noticed that less talented (in my view) people were doing well (in their employerʼs eyes) by not having any design pretensions. Draw your own conclusions, but never lose your design ambitions. 8. Write your way to the top Record, write, and broadcast if you’re good at it. Don’t just design. In San Francisco, in the early 1990s, I got to work alongside Lawrence Halprin on various projects. He was quoted as saying that his secret to success was as much about writing about it as doing it. Often, writing about it or expressing your ideas in alternative mediums is part of the creative process of “doing it.” The world needs more good communicators whose objectives have integrity. While you are at it, collect and record your own experiences, as a good writer would do. They will be useful in “selling” yourself, perhaps starting with a website. 9. The specialist After the initial foundational experience, specialize if you can and now know which area, e.g. urban design, land art, landscape journalism, whichever best suits you. For me, that meant specializing in a site art-based approach, enhanced by my experience.

What’s your specialty? – Street decorated with colored umbrellas. Madrid,Ge tafe, Spain; credit Lukasz Janyst / shutterstock.com

The know-how of being a landscape architect is an advantage in this case over “fine art” graduates (unless you have no artistic vision). Equally, I always saw myself as being better at creative writing than project management. Itʼs all about being creative, ultimately, and following and growing your strengths; just different levels of function, problem solving, and practicability.

The modern profession, certainly in the U.K., now encourages specialization. We need extra skill and power at visual impact analysis, for instance, as this is a growth area. You may be typecasting yourself, but there are advantages if you do this in a growth area. This is the opposite of the view that used to be held that a more “jack of all trades” approach would ensure success.

10. Grow your connections Cultivate your contacts as they grow — therein lies opportunity. Friends you work with or who you cross paths with in connection with your career may provide fruitful opportunities either now or in the future. In particular, I always try to keep in touch with many of my ex-students. Years later, I have worked with several of them, and my enjoyment and trust is enhanced by the knowledge that I hung on to them as contacts. People usually only create employment for others if there is some mutual benefit. Ideally, they will only work with people they get along with, respect, trust, and who share the same vision/beliefs. That is made considerably easier if you donʼt meet for the first time at an interview. In summary, work hard at what you enjoy, even if this leads you off on a tangent. Be realistic in your expectations — it doesnʼt prevent you from being ambitious. Trust your instinct to lead yourself, and embrace those who open up opportunity and who you get along with, even if it means changing paths drastically. If in doubt, there is no shame in just surviving tough times. Put a positive spin on everything. Your life can tell a great story, so collect and record that memory as you go. Interest others in that journey –communicate well. Be honest about your strengths and weaknesses, and work more on the former, moving away from the latter when you can. Be in awe of interesting people, not of fame alone. Have fun and travel. Remember that even creativity relies on work and, in turn, some level of skill and knowledge — just not knowledge for its own sake. Einstein As Einstein once said — “never memorize something that you can look up”. Keep your mind free for invention. Donʼt forget that landscape architecture is half business, half environmental design. How you interpret that is up to you if youʼve forged your own way — or up to your employer to determine as long as you are not the boss. Look for the employer who makes decisions through discussion, consensus, and shared vision — and be that person yourself.

A man of great insight; Albert Einstein Memorial in at the National Academy of Sciences in WashingtonDC, USA; credit: Hang Dinh / shutterstock.com

Article written by Brodie McAllister

Brodie McAllister has spent the last 25 years dividing his time between the design of large urban parks and squares and urban strategies to garden design and land/site art, in Asia, France, the U.S., and the U.K. This was interspersed with teaching. He has received a number of awards, published many articles, and received publicity in a wide range of books and magazines. He can be contacted at www.brodiemcallister.com Featured image: dotshock / shutterstock.com

Reverse Graffiti – Activism, Art or Vandalism?

Also known as clean graffiti, reverse graffiti is essentially the act of removing dirt or dust from dirty surfaces in order to form an image or text. This act can be done from using your own little finger to write ‘clean me’ on that van you can see, to a using a cloth on a wall, or in some cases a high power washer for those works on a grander scale. Reverse graffiti, operates within what most people call ‘a legal grey area.’ That is to say, the act of cleaning something isn’t illegal but that it results in creating an image on someone else’s property means it may be seen as trespassing.

Moreover, whilst cleaning walls is not illegal, using this method as a form of advertising may be. Recently reverse graffiti has been commandeered by the advertising industry. In most places you must have a license to advertise in a public space, hence the fact that clean graffiti is seen to function in this legal ‘grey area.’ Environmental Activism Generally, the father of Clean Graffiti is seen as one Paul Curtis, aka ‘Moose’ Moose himself has done both personal clean graffiti and ‘official’ work for advertising agencies but also for companies in the UK such as Transport for London. He’s even worked for the British police on an anti-gun campaign. Below: Moose in Belgrade As reverse graffiti is temporary, biodegradable and uses nothing to really impair or cause a negative impact on a surface, it is seen as an environmentally friendly work of art (in contrast to more traditional forms of graffiti) and is one of the reasons it has been adopted so readily by guerilla marketing agencies. Moose himself says “it is an act of refacing not defacing”. Another prominent mover and shaker is Brazilian street artist Alexandre Orion. José de Souza Martins, Professor of Sociology at São Paulo , University, comments that the signature skulls of Orion’s work are a type of memento mori regarding our relationship with pollution. Art or Vandalism? As mentioned, what is often seen to be illegal about reverse graffiti is its use by media agencies to advertise particular companies, campaigns and products. Gaining a license to advertise inevitably legitimizes the graffiti. In certain places it is still frowned upon, and in some areas, municipal powers adamantly regard it as illegal – not even allowing licenses for advertising agencies. So what about personal, non-commissioned reverse graffiti? As with, ‘traditional graffiti’, that is to say tags, throw ups (larger tags), and sentences or words, it begs the question, is it art or vandalism? The first reactions to ‘traditional’ graffiti by the general public where overwhelmingly negative – and often still are. In 1996 Tim Cresswell argued that reactions to graffiti were negative because they represented dirt, which we don’t like. Dirt turns up in unwanted places and so does graffiti. As such it is a threat to order. Hold on you say, reverse graffiti is about cleaning not being dirty. It’s the opposite! Yet it may still be seen as a threat to order because the act is undertaken without authorization from official channels. Reverse graffiti refuses to comply with the perceived rules of an urban space. Herein lays its illegality and thus it is, technically, vandalism. But that is not to say it’s not art. Indeed, if we take a look at the history of art, most new movements have been seen as; radical, corrupting, degenerate, vandalistic, hedonistic and so on. Yet invariably, no one would now argue Vincent Van Gogh (famously never sold a painting in his lifetime) did nothing for art, or moreover, the society which holds that art dear. Likewise, few people will say that the recent destruction of 5 Pointz passed without a murmur or that its establishment failed to contribute to art, society or New York’s history. At the end of the day reverse graffiti – like its wider family: street art, graffiti, living graffiti and subtraction graffiti – calls into question the dialectic between public and private space and raises questions about how places become what they are and who says what they can be. Whose cityscape is it anyway? What’s more detrimental to your streetscape? A piece of attractive but non-commissioned art, or a dirty grey wall? Check out GreenGraffiti® Presentation and learn more.. Article written by Sonia Jackett Images courtesy of GreenGraffiti5 Common Habits of Successful Landscape Architecture Students

Studying landscape architecture is hard. The old adage of ‘work smart, not hard’ is very enticing. Whilst there’s no escaping hard work on a landscape architecture course, you can make sure you’re working smart! Here we take a look at the five most common habits of successful landscape architecture students. 5. Bouncing off your classmate At the beginning of our undergraduate course one of our lecturers shared this pearl of wisdom with our class “you are each other’s greatest resource”. The most successful students know who has experience working in construction or whose plant knowledge is particularly good. Rather than spend ages searching the internet for answers these successful students ask the right person, who usually knows the answer and can point to a useful text.

4. Napping Naps have the ability to consolidate learning, improve memory, increase alertness and creativity and reduce levels of stress hormones. It can be tempting to spend as much time as possible in the studio, but successful students often take time to take short naps, and reap the benefits in their learning and work. 3. Goal setting and scheduling “Most people spend more time planning their summer vacation than they do their lives” – John Assaraf – entrepreneur, business coach and author. The truth is 10 minutes a day of goal setting and scheduling can save you hours, days and possibly weeks, freeing you up to revise your projects and turn that C grade into an A grade. Before you start your day, plan it! A great piece of FREE online software to help you plan your day can be found at Simpleology 2. Study/life balance Being a landscape architecture student is hard work, and can be demanding. The most successful students recognize this and take time to look after themselves. It can be tempting to eat sugary foods for an energy rush and drink lots of coffee. Successful students will make time to exercise, eat well and socialize. The path to becoming a landscape architect is more of a marathon than a sprint Pacing yourself and giving yourself good ‘fuel’ is essential. 1. Jotting down ideas and capturing inspiration It seems simple, but it is one of the most useful things any student can do. The most successful students always have a pocket sized notebook with them, and make annotated sketches in class and outside to record information, explore ideas and work out problems. Always have your pocket sized sketch pad at the ready. Photo credit: jurie/shutterstock Through observing the habits of successful students, and implementing them in your own work, you can overcome your weaknesses and maximize on your strengths. Make a New Year’s resolution to adopt some habits from successful students to improve your own learning. Whether it’s just getting into the habit of daily planning, or always carrying a sketchbook into class, you’ll be glad you did! Article written by Ashley Penn. Feature image: bikeriderlondon/ shutterstock

Always have your pocket sized sketch pad at the ready. Photo credit: jurie/shutterstock Through observing the habits of successful students, and implementing them in your own work, you can overcome your weaknesses and maximize on your strengths. Make a New Year’s resolution to adopt some habits from successful students to improve your own learning. Whether it’s just getting into the habit of daily planning, or always carrying a sketchbook into class, you’ll be glad you did! Article written by Ashley Penn. Feature image: bikeriderlondon/ shutterstock

Crimes Against Horticulture: Interview with Billy Goodnick

In this interview, LAN talks with Billy Goodnick, founder of Crimes Against Horticulture and author of the book “Yards”. We discuss CAH’s origins, mission, role, importance, reception … and … testicle-shaped hedges. We even have Billy answer that one divisive question: Who is the biggest perpetrator of Crimes Against Horticulture — the landscaper or the designer? How did Crimes Against Horticulture come about? “I was writing for EDHAT and was part of the Santa Barbara Beautiful Awards (a competition for the most beautiful gardens) and decided to take some photos that I had collected through my work and do the Santa Barbara Not So Beautiful Awards, and I had categories like the silliest place to put a Bougainvillia, and continued doing the “Not So Beautiful Awards” the following year. About two years ago, I came across some of the Santa Barbara Not So Beautiful photos on my computer and set up a Facebook page called “Crimes Against Horticulture: When Bad Taste Meets Power Tools”. I started uploading some photos and redirecting people from my own Facebook page, and now it’s grown to over 2,000 fans and I have people from all over the world posting and contributing to the page.  Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB The only other thing I can also attribute to founding CAH was that as a teenager, I used to cut out what I thought were ugly brides from the LA Times in the newlyweds section and stick them up on my bedroom wall. Then people would come over and disagree with which brides was ugly and which wasn’t, kinda eye of the beholder type of thing. So, maybe some of that fascination spilled over into CAH … and why everyone hates me!

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB The only other thing I can also attribute to founding CAH was that as a teenager, I used to cut out what I thought were ugly brides from the LA Times in the newlyweds section and stick them up on my bedroom wall. Then people would come over and disagree with which brides was ugly and which wasn’t, kinda eye of the beholder type of thing. So, maybe some of that fascination spilled over into CAH … and why everyone hates me!

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB What has the response to CAH been like? On some blog posts, you’ll see some nasty comments like “Who are you tell us what to do”, “You’re a b@$#@$d”, etc., but my response has always been that it is not just about aesthetics, but the sustainability, the green waste, and the fact that somebody gets paid to do it. Fortunately, I never hear back from the people I have shamed. However, there have been a few instances from people who have a stick up their backside. Most people who come to the Facebook page are there for the humor and I’m just preaching to the choir. However, I don’t have any real way for gauging the reaction from those projects which are shamed on CAH. What do you feel is the solution to preventing CAH in landscape architecture? Better planting knowledge. I’m so surprised to see many garden design, landscape design, and landscape architecture courses with little focus on botany, spatial planting design, and right plant right place. But knowledge is only one part of the problem; another is the working knowledge of contractors who are planting and maintaining the shrubs, trees, and perennials that are chosen by the designer. So unless you have each party taking responsibility for their actions, you’re always going to have crimes against horticulture.

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB What has the response to CAH been like? On some blog posts, you’ll see some nasty comments like “Who are you tell us what to do”, “You’re a b@$#@$d”, etc., but my response has always been that it is not just about aesthetics, but the sustainability, the green waste, and the fact that somebody gets paid to do it. Fortunately, I never hear back from the people I have shamed. However, there have been a few instances from people who have a stick up their backside. Most people who come to the Facebook page are there for the humor and I’m just preaching to the choir. However, I don’t have any real way for gauging the reaction from those projects which are shamed on CAH. What do you feel is the solution to preventing CAH in landscape architecture? Better planting knowledge. I’m so surprised to see many garden design, landscape design, and landscape architecture courses with little focus on botany, spatial planting design, and right plant right place. But knowledge is only one part of the problem; another is the working knowledge of contractors who are planting and maintaining the shrubs, trees, and perennials that are chosen by the designer. So unless you have each party taking responsibility for their actions, you’re always going to have crimes against horticulture.  Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB Who is the biggest perpetrator of Crimes Against Horticulture: landscapers or landscape architects? While some landscape designers are at fault by specifying a plant species that will outgrow a space within a year, landscapers and contractors are just as guilty by hacking away at evergreen hedges with a trimmer until you end up with a phallic hedge and a set of green testes.

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB Who is the biggest perpetrator of Crimes Against Horticulture: landscapers or landscape architects? While some landscape designers are at fault by specifying a plant species that will outgrow a space within a year, landscapers and contractors are just as guilty by hacking away at evergreen hedges with a trimmer until you end up with a phallic hedge and a set of green testes.  Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB What is the future for CAH? To raise greater awareness among the public of the utter stupidity of “supposed” professionals and of the potential sustainability of our landscapes, if managed properly, through twisted humor and comic wit. Check out Billy’s book “Yards: Turn Any Outdoor Space Into the Garden of Your Dreams” Interview conducted by Joe Clancy

Image credit: Billy Goodnick |CAH FB What is the future for CAH? To raise greater awareness among the public of the utter stupidity of “supposed” professionals and of the potential sustainability of our landscapes, if managed properly, through twisted humor and comic wit. Check out Billy’s book “Yards: Turn Any Outdoor Space Into the Garden of Your Dreams” Interview conducted by Joe Clancy

10 Things You Must Know If You Want to Study Landscape Architecture

Trying to figure out your calling can be a tricky thing. This is especially true if you are interested in landscape architecture, an interdisciplinary field with open-ended opportunities. If you are thinking about studying landscape architecture and you do not want your choice to be a reckless one, check out the following 10 steps that can give you a deeper understanding of the field, the qualities needed to study landscape architecture and the career prospects that await you:

Study Landscape Architecture

10. Notice the spaces around you This one might seem obvious, but if you want to spend your life designing spaces, you might as well start being more attentive to the way they are shaped. Observe how people use a certain place (be it a square or a street or anything else). Try to understand its dynamics and the materials used to create it. 9. Do you have what it takes? Designers surely come in all forms and shapes. But there are some qualities needed in order to succeed in the field. These include patience, heightened senses and attention to detail, the ability to work in an interdisciplinary team, and a willingness to spend long hours drawing on a computer. If you do not have it in you now, it is important that you be willing to acquire it.  Image via Shutterstock

Image via Shutterstock

8. Talk to professors

The easiest way to answer your doubts and questions is to visit the universities you plan to apply to and talk to the instructors. Go prepared with a set of questions. Be sure to talk to more than one teacher; each design instructor usually has his or her own school of thought, and this way you will avoid gaining one narrow image of the vast world of landscape architecture.

7. Attend a final-year presentation

If you can manage to be in the eye of the storm — where all the serious landscape architecture student business takes place — then you cannot possibly be more ready. Being present at a final-year student’s defense will give you all the answers about what is eventually expected from you. Don’t hesitate to ask questions if there is something you do not understand.

Image credit: Scott Renwick | end of year presentations University of Gloucestershire

Image credit: Scott Renwick | end of year presentations University of Gloucestershire

6. Read the course descriptions carefully

The next university-related step would be to read the list of courses provided for landscape architecture students, as well as the course descriptions. Try to understand what each course requires and whether it is something you would be excited about. Don’t panic if there are some that sound less interesting. Trust me: No one ever falls in love with all his or her courses. (I still remember my Technical Drawing class: Yikes!)

5. Study the job market

Find out what awaits you in the real world before even starting your studies. Try to get in touch with graduates from the same major and see what they have been up to. If the country where you want to work does not have great opportunities for landscape architects, you should be aware of it and be prepared. Also see our feature article Do you have what it takes to stand out in the job-hunting market?

4. Talk to professionals

While final-year projects are a quite significant showcase, nothing gets you closer to how things are done in the real world than projects in the workplace. Meet with professionals working in the field. Have a look at their projects and interrogate them about the process. Take note, as well, of the physical implementation of the designs.

3. Read about the field

To have a grander view of landscape architecture, browse the internet and magazines for worldwide updates on the field. For information on the best places to hunt for inspiration, check out our article Top 10 Online Resources for Landscape Architecture.

2. Take drawing classes

Knowing how to draw before starting to pursue your degree is not a requirement. Nevertheless, having an urge to draw is a major quality needed in a landscape architect. So test yourself with drawing and see if you enjoy it. Some architectural departments offer summer drawing classes for those who are about to start a design major. Maybe the university you apply for does, too! Check out our book review on Freehand Drawing & Discovery by James Richards

1. Make sure you have the right motivation

Individuals choose their majors for all sorts of reasons. Make sure that yours is not that “it’s cheaper than the other degree I wanted to pursue” or “the campus is located in a really cool area”. My brother once said (and he was so right) that when you are about to choose a major, ask yourself “what is something that I would be delighted to do even if I wasn’t getting paid for it?” If landscape architecture is a positive answer for that, then you are in the right place. To all of you potential landscape architecture students, I truly hope that this article brought you the answers you came here seeking. Still looking for more motivation? Have a look at our article 10 Great Reasons to be a Landscape Architect. If all that doesn’t help you make up your mind, maybe you should watch this video: Article written by Dalia Zein

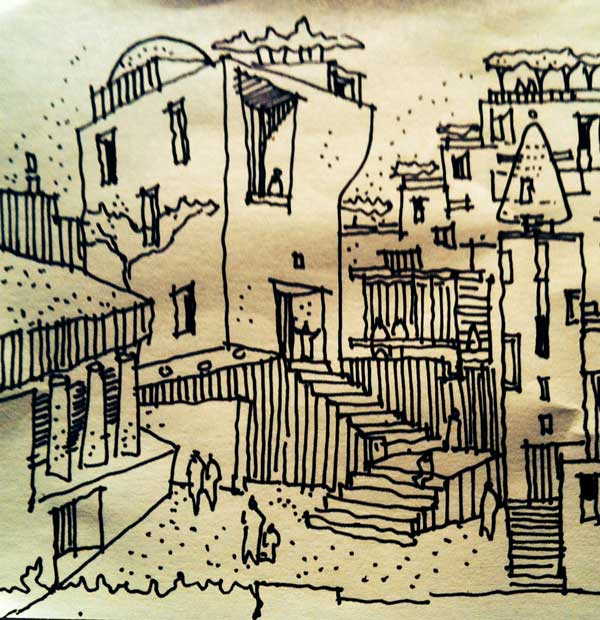

Sketchy Saturday l 010

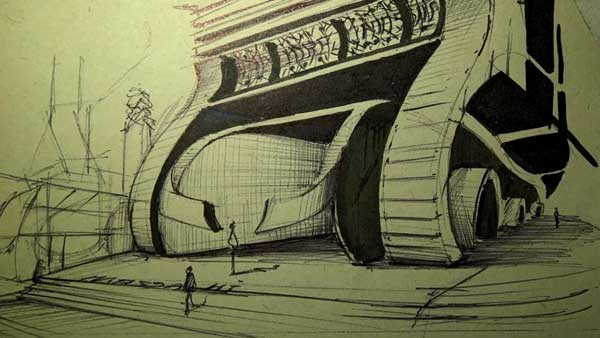

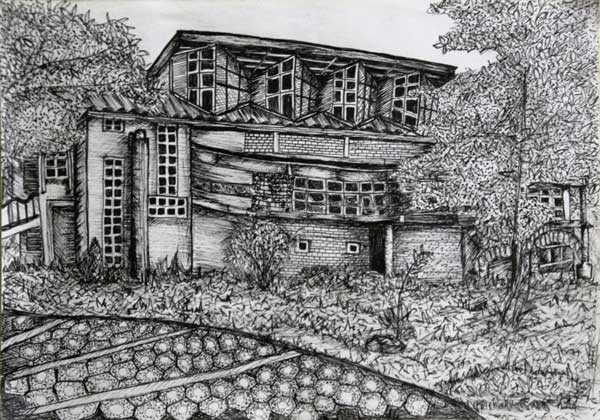

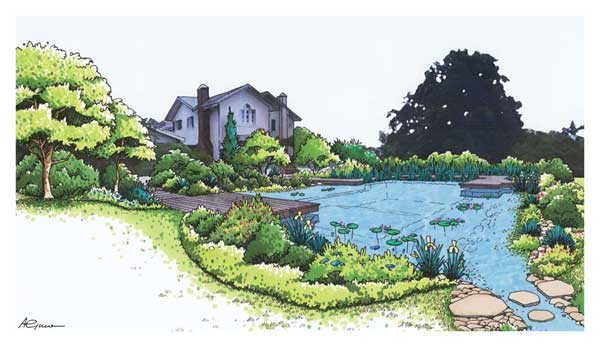

This Saturday we’ve reached our tenth edition of our beloved Sketchy Saturday! I hope you’ve had as much fun as we had admiring and learning from all the artistic, technical and detailed sketches from our readers. As this is a special edition, a mini anniversary so to say, we tried to pick the best of the best, looking out for essentials like style, mediums and perspectives. Enjoy this week’s Top 10! No. 10 by Wiktor Kłyk, landscape architect

‘This is a sketch for an outdoor garden. The concept was based on symmetry and geometrical shapes, in respects to the outdoor furniture as well as the trees and plants that accompany them. The perspective of the sketch is semi-aerial, so that we can see how the atmosphere in the garden will be. It features a small pond, benches and rows of trees and flowers set geometrically to the whole concept. The sketch was done in pen and colour.’ No. 9 by Anton Comrie, director at PrLArch ‘This sketch is called ‘Urban Utopia’ and I made it with a felt tip pen on a 100mmx100mm white post-it note. When exploring ideas in design, it is often a matter of putting pen to paper and starting to draw. With this as an example, it does not matter what the drawings are at first. They are, in a way, just like stretching exercises before a workout. Personally, I find this way of exploration liberating and fun while offering different angles of approach to a design. As landscape architects, drawing assists greatly in making us better designers rather than makers of good drawings.’ No. 8 by Van Cam Hoang ‘Landmark is a construction company which is specialised in council kit form. This is the viewing platform product of Landmark. The hand sketch perspective helps us to imagine how the platform looks e and how much people could enjoy it. The perspective gives us the view of the surrounding landscape as well as shares the enjoyment of the viewers. ‘ No. 7 by Wiktor Kłyk, landscape architect ‘Gardens are essential in urban areas. This one fits great among the surrounding buildings and it also holds true to their geometry in its design. Its style is quite minimalistic, with simple plants and a few covered and semi-covered leisure spots. Wood is quite prevalent as a material, but overall, the garden can be a nice spot for meditation or a coffee break. I drew it in pen and colour.’ No. 6 by Kiemah Hakiemah ‘This sketch shows a recreational park and activities that bring people together within this gathering area. Here we tried to fulfil the parks requirement as an area for connection with open spaces or an area set aside for recreation, which includes the delightful aesthetic result of enhancing the space.’ No. 5 by Hamidreza Massahi, designer from Iran The style of this sketch is quite futuristic with a gloomy note, but it shows how great design comes by just by putting down your ideas on paper. Sketching spontaneously and doing designs that come just out of your head on the spot, can made for the best sketchy work and later to great real-life designs. ‘This sketch was made on A4 paper and I did it in about 20 min. I tried to capture the best view of my idea and to show the scale of the building. I drew a bus and some buildings in the background on the left and some human figures. I did this sketch with just a pen and marker, without a model or erasing, just from my imagination.’ No. 4 by Attila Tóth, Slovak University of Agriculture, Nitra ‘This picture was sketched on a sunny summer’s day at a pond in Hungary called Római tó with the aim to capture the calm and idyllic atmosphere of the water scenery. The unruffled surface of the pond and the pleasant tiny fishing cottages are framed by tree and shrub compositions. The reed and the small pier impart depth to the sketch and draw you into the composition.’ A basic pencil sketch in itself, this is the most definite and pleasant way to capture a detailed view of a special perspective. No. 3 by Jehanna Abdulkarim, LA student from University of the Philippines Diliman ‘I made this sketch when I was a 1st year LA student and we were asked to do some sketches for our class. This is a sketch of UP Diliman College of Architecture Building 1I was drawn towards its unique architectural design among other buildings in the campus. The medium used was pen and ink.’ No. 2 by Eirini Mouka, landscape architect ‘This is a drawing from a place I visited in Budapest in 2011, during my participation in Erasmus IP, at the University of West Hungary. I used pencils and pens for drawing, and Photoshop for painting.’ No. 1 by Alexandre Guillet, Landscape architect at J.N. Jardins naturels SA., Switzerland ‘This represents a natural swimming pool project in the area of Geneva, Switzerland. The perspective was elaborated by J.N. Jardins naturels Chavornay SA and illustrates the integration in the garden using hand sketching (the house plants) and Photoshop (the water and background).’ I hope you enjoyed our tenth edition of Sketchy Saturday. We love that you guys are such avid drawers and send us your best work. However, if you want to improve on your LA designs, why not check out our book review of Drawing for Landscape Architecture by Edward Hutchison. Also, browse through Sketchy Saturday No.009 to other amazing sketches! Sketchy No. 011 is soon to come! But until next time, don’t forget to send your work along with a short description of the sketch to get a better chance of having your work selected for our weekly Sketchy! See you next Saturday! Article written by Oana Anghelache.