The COVID-19 public health and economic crisis has allowed and, in some instance, forced cities to experiment with the use of streets for temporary accommodation of recreation, events, dining, protest, school, and as spaces for the public to enjoy time outdoors. But over the course of history, many U.S. cities have designed and used some streets for park and civic gathering purposes and not just moving people. We suggest we can learn from both history and these recent experiments in street uses so that these temporary experiments can become more permanent and high-quality long-term solutions.

In 2014, landscape architects and planners from Design Workshop authored an article in Planning Magazine titled “Recreation in the Right-of-Way”, which made a case for including recreation as a metric for Complete Streets design. In this research we found reasons street functions have been limited historically, identified common barriers to change, and pointed to lessons from successful expansion of street purposes. This is an ideal moment to capitalize on current interest and momentum to put these lessons into action by advocating for long-term solutions.

In recent years, planners and designers have thoroughly dissected the “why” behind roadway design. Some streets reflect travel demand model requirements, some are outcomes of policy and institutional management structures, while other conditions reflect funding or grant procedures and requirements. Regardless, street design is always an exercise in establishing priorities as matters of public policy. We feel that defining and expanding this public policy component can be key to significantly enhanced use of our cities’ streets.

Cities across the country, along with their state transportation departments, are adopting complete streets policies, and using various transportation-related performance measures to rank results. Design Workshop is involved in many of these and related transportation planning and design projects that consider land use, economic development, green infrastructure, air quality improvements, placemaking and branding along with the needs to move people. This has represented a significant shift in approach and priorities; however, we have yet to fully understand the other changes in behaviors, priorities, funding and policy that have occurred and continue to develop during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Brookings Institution notes that up to half of American workers are currently working from home, which is more than double the fraction who worked from home within the past two years. Many companies interviewed as part of this study have committed to a future of remote work for at least 20% of their staff, which could mean a significant reduction in commuting traffic on streets in the long term. Travel patterns to schools are also in flux. As dedicated funding for parks and open space continues to dwindle during the COVID-19 crisis, the National Recreation and Parks and Recreation Association (NRPA) has noted that “now is the time for park agencies to align investments with other local programs and policies, to tap new funding in creative ways, while benefiting the community.” As our priorities continue to shift, we should consider recreation-broadly defined- as part of the Complete Streets definition. Recreation should become a critical factor within the prioritization process that embodies street design.

Over the past six months, shelter-in-place policies and closure of gyms, recreation centers, and some neighborhood parks and playgrounds to slow the spread of virus have caused people in cities and small towns to turn to streets for outdoor recreation in many forms, from simply walking to biking and other non-motorized activities. The Trust for Public Land estimates more than 100 million people across the country do not have a park within a 10-minute walk of home. In places constrained in meeting park provision goals, existing street rights-of-way should be evaluated as potential spaces to meet these critical standards. Streets can still serve to move people while also serving as linear parks, pocket parks, desirable places for strolling, playing table games, interacting with art, gardening, seating, exercise and play. By avoiding the purchase of new park land and removing it from the tax rolls, cities can further leverage the public land they already own and enhance quality of life in the process of saving money.

In the U.S., more than $180 billion dollars (or 6% of direct general spending) is invested into our highways and roads annually, according to the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. We feel this significant investment should be directed to solving more than vehicle mobility needs, and many ostensibly “temporary” COVID-induced adaptations to streets can be made permanent enhancements to the public realm. In addition, as we move forward from the pandemic, our parks and open space planning methodologies need to assess opportunities for non-traditional recreational spaces to improve equitable access to all forms of recreation, including the opportunities to utilize street right-of-ways.

In studying successes and shortfalls, the following are some of the lessons we have found to be universal for U.S. cities.

Lesson 1: Establish or Realign Public Policies. Cities must establish the goals of broader usage of streets as matters of public policy. Once the policies are established, the procedures to implement and maintain those policies can ensue.

Lesson 2: Coordinated Planning. City and regional planning typically includes numerous system-wide plans for bicycle and pedestrian facilities, comprehensive plans, transportation master plans, complete streets, downtown visions, sustainability, and parks, recreation and trails–all addressing goals for community health and infrastructure planning. While these plans are intended to ultimately reference each other, they rarely are coordinated to examine complex demands on a roadway. When working at the system level, these planning efforts can and should be undertaken simultaneously to coordinate identification of multiple desired purposes of streets.

As an example, Adams County in Colorado is currently undertaking three system-wide plans at once, including a Comprehensive Plan, a Transportation and Mobility Plan, and a Parks, Open Space, and Trails Plan. This integrated effort has provided the opportunity for Design Workshop to use park accessibility gap assessments to direct land use planning and transportation infrastructure improvement for such things as a civic plaza and outdoor exercise equipment within a transit hub.

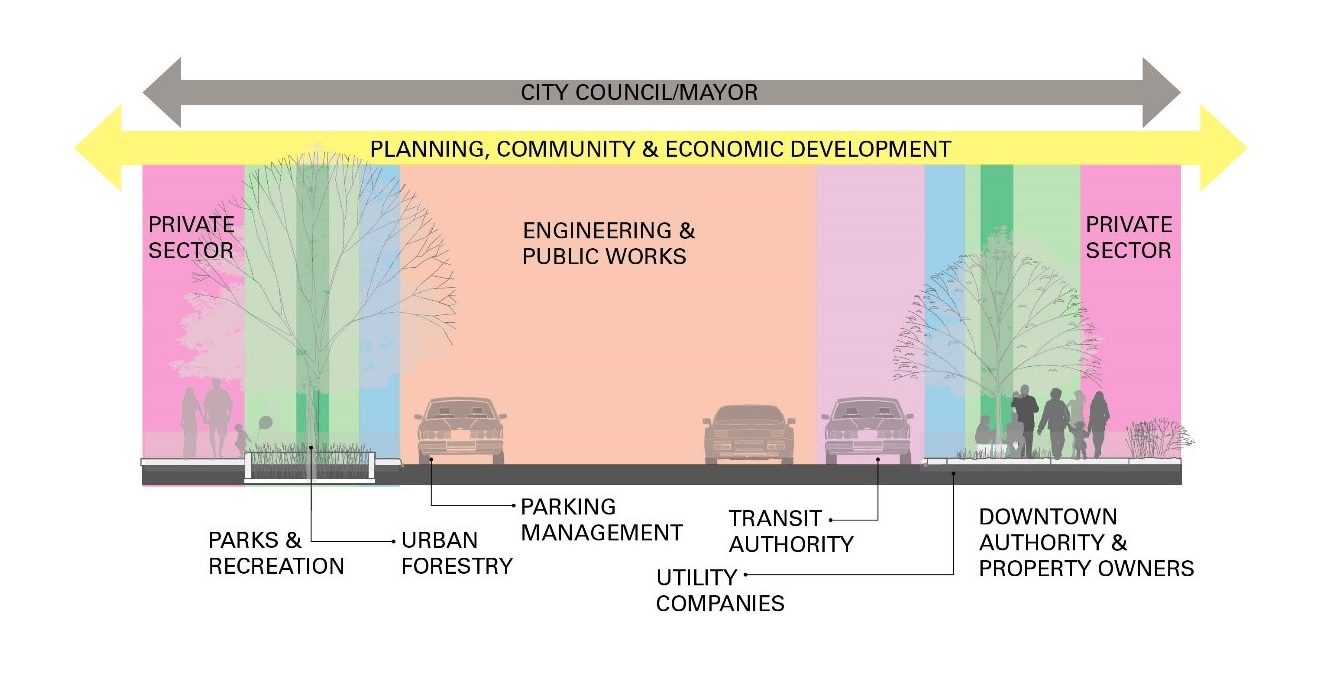

Unifying objectives of multiple plans and departments/entities is key to implementing non-standard street designs. Image: Design Workshop

Lesson 3: Unify siloed departments’ efforts on street design matters. Making the invisible lines of street management responsibilities visible and coordinating early and often is necessary for making less-traditional street use feasible. Every community and street have a different overlay of responsible entities that may include public utilities, stormwater management, urban forestry, Business Improvement District, downtown partnerships/authorities, special events, parks, fire/emergency response, transit entities, city engineering, public works, community development, parking management, street maintenance and private sector interests. Some may influence design standards and others may focus on maintenance or programming needs. When non-standard approaches, different objectives or conflicts are encountered, it is often best addressed in multi-department collective problem-solving discussions.

Lesson 4: Challenge and test the relevance of all parts of existing streets. For examples, ask questions like: Is that right turn lane needed, or could it become part of a small new neighborhood plaza to host the annual tree lighting? Does this street need a center lane, or could it become an open space for trees and stormwater infiltration?

Funding sources and their requirements may be clues in answering these questions. Some of these requirements may lead to providing a “solution” that only checks a funding box and isn’t necessarily reflective of what the community desires. Federal transportation grants do not prioritize all kinds of “recreation” – they mostly require alternative modes of transportation, bike lanes, etc. An alternative funding source, for example, Housing Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) can be used to address a range of public infrastructure and facility projects that benefit low-income communities. Know the policy framework. Are you questioning a street within a city jurisdiction or a state DOT? The policies, priorities and regulations within each may differ greatly.

Lesson 5: Advocate. While performance measures are now a standard approach in corridor planning and street design, few address the recreational and parkland qualities of the street environment. Urban designers should promote this approach to organizations such as SITES, NACTO, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, and WalkScore–and advocate for these objectives within funding proposals and grant applications.

Triangle Plaza in Denver serves as an urban stage for people-watching and interaction, located on an abandoned street right-of-way linking Union Station and the Pepsi Center. Anchoring the plaza’s southern edge is the ‘swing forest,’ which consists of custom-designed swings affixed to curved railroad rails.

Image Copyright: Brandon Huttenlocher photographer / Design Workshop, Inc.

Lesson 6: Look for models that have stood the test of time. While urban designers and engineers may differ on design approach or standards (lane widths, turning radii, turning movements, access drives, etc.), real-world examples are a critical communication tool for reaching consensus. Streets around the world have served as portals for recreation throughout history. Strolling, people watching, chess games, reading – these are all forms of recreation. The original design intent of many of the world’s famous boulevards and promenades was to inject a recreational function by serving as linear parks within newly developed areas of cities, sometimes dedicating 70% of the right-of-way to “recreation” as we have defined it here.

To further understand these spaces and their intent, designers can easily reference “The Boulevard Book,” and “Great Streets,” both by Allan Jacobs. Jacobs notes in “The Boulevard Book,” that streets respond to many issues that are central to urban life, including livability, mobility, safety, interest, economic opportunity, mass transit and open space. While Jacobs’ grand examples like Boulevard de Rochechouart in Paris and Las Ramblas in Barcelona offer an inspirational starting point, there is a growing catalog of examples of all scales of intervention – some simply reclaiming turn lanes to create a corner plaza space or prioritizing recreational spaces over parking in targeted areas. Other examples that may literally be built upon are often found in the local historical record. Many cities that existed before the motor age were creative in their use of street space and older photos, paintings and post cards can often serve as good references.

The Colorado Springs Downtown Parks Master Plan designed Alamo Park to overtake one row of on-street parking and a travel lane to create a pedestrian promenade and festival street, providing infrastructure for market and event booths, outdoor dining, and food truck stalls. Source: Design Workshop

We believe it is time to reclaim the street for a more comprehensively-defined set of purposes — to accommodate the diverse needs of a community including recreation and parkland. As we navigate the COVID-19 pandemic and our exercise in prioritization shifts, we should reference these precedents to make the case for measuring the area devoted to street recreation and park space within our street rights-of-way. Jacobs notes in “The Boulevard Book” that public streets should seek to serve multiple purposes, acknowledging that “not all streets can or should do so, but some can and must.” Streets have the capacity to integrate rather than divide neighborhoods and communities, and within some, the capacity exists to further city-wide or regional targets for open space and recreation. Inequities in park quality and access have always existed in communities across the U.S., but the current pandemic has further exacerbated this challenge. Streets can provide many opportunities for public reinvestment, and by providing the necessary community space needed for mental health and physical safety at relatively low costs, can thereby create a rich set of sustainable public benefits for all.

—

Authors:

Anna Laybourn, AICP is a Principal at Design Workshop, an international design studio providing landscape architecture, planning, and strategic services. Anna’s diverse experiences in community, regional, and land planning are united by a focus on people and planet. She forges the natural and social sciences in her work on parks and open space master plans, transportation infrastructure design, and development proposals.

Sara Egan, PLA, AICP, LEED AP® BD+C is an Associate at Design Workshop’s Chicago studio. Sara’s experience at the implementation scale informs the execution of her work at the strategic and regional scale, focusing largely on transportation corridors and public realm design.

Lead Image: As density increases in downtown Wheaton, Illinois the Downtown Plan identified strategic creation of new public spaces including the transformation of a section of angled parking into a permanent public plaza for outdoor dining and events. Image Copyright: Brandon Huttenlocher photographer / Design Workshop, Inc.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured

James Lentz

Seventh paragraph, this article states $180 million is spent on roads and highways, but the sourced figure is $180 billion.

Land8: Landscape Architects Network

Thanks! Corrected.