A few weeks ago, when we were all shaken awake by the Black Lives Matter movement, Black landscapes and our treatment of them as landscape architects began to occupy my mind. The very fact that it should have to take a movement of this magnitude for this topic to occupy some of our minds as designers is an issue that requires attention. I like to think that as landscape architects we have a unique role of protecting and preserving the stories and existence of those who have come before us. By genuinely understanding the culture, politics, and lives of a given community we are designing for, we get to use our skills of design and storytelling, and take part in highlighting a group of individuals and their lives on the lands that we inherit and get the opportunity to creatively. To be an active participant in what we were learning individually, I began conversations on this topic and similar issues on the Awescapes page. Received with great enthusiasm and feedback, the conversation lent itself to a survey, an extended conversation on race and landscape architecture, and the Ideas Pinup. The intention of the Ideas Pinup has been to take what we, as landscape designers and architects, are learning and unlearning about and being active participants in relearning and reshaping our design approach, with hopes that moving into the future we are more aware of our design decisions and their impacts on future generations.

It’s no small task once you begin to look at the sites we design through the lens of honoring and storytelling, yet we often don’t dedicate or have the time, the client, or the drive to be able to dive into the history of lands that we draw on. As a result, many people who have once walked on those lands are forgotten and their stories disappear into thin air. Black landscapes are important because they give us a glimpse into the stories of Black Lives that Matter, Black Lives that need to be protected, and Black Lives that have and continue to contribute so much to the American existence, culture, politics, and livelihood.

To better understand how we, as a field, are currently doing in this aspect, and how we can improve our ways going into the future, I began to look into the past, to get a sense of how landscape architecture has served historically Black landscapes and spaces. I began to realize that we often do not speak about historically Black lands, whether in our classrooms, in our conferences, or just topics of discussion, but I specifically began to wonder how many landscape architects and designers were aware of or had been educated on Seneca Village, since most everyone learns about Central Park at the very beginning of their landscape architecture education.

Conducting a short survey on Awescapes quickly revealed that from 55 participants, only 60% had heard about Seneca Village, and only 23% of them had learned through their education (77% had learned through personal research, available in the highlights section of Awescapes on Instagram). This showcases that while almost everyone within landscape architecture in America knows about Central Park, its design elements, and Fredrick Law Olmsted, in great detail, only 60% know that to create Central Park as it stands today, the first freed African American settlement, Seneca Village, at about 225 residents, was destroyed through eminent domain.

SENECA VILLAGE

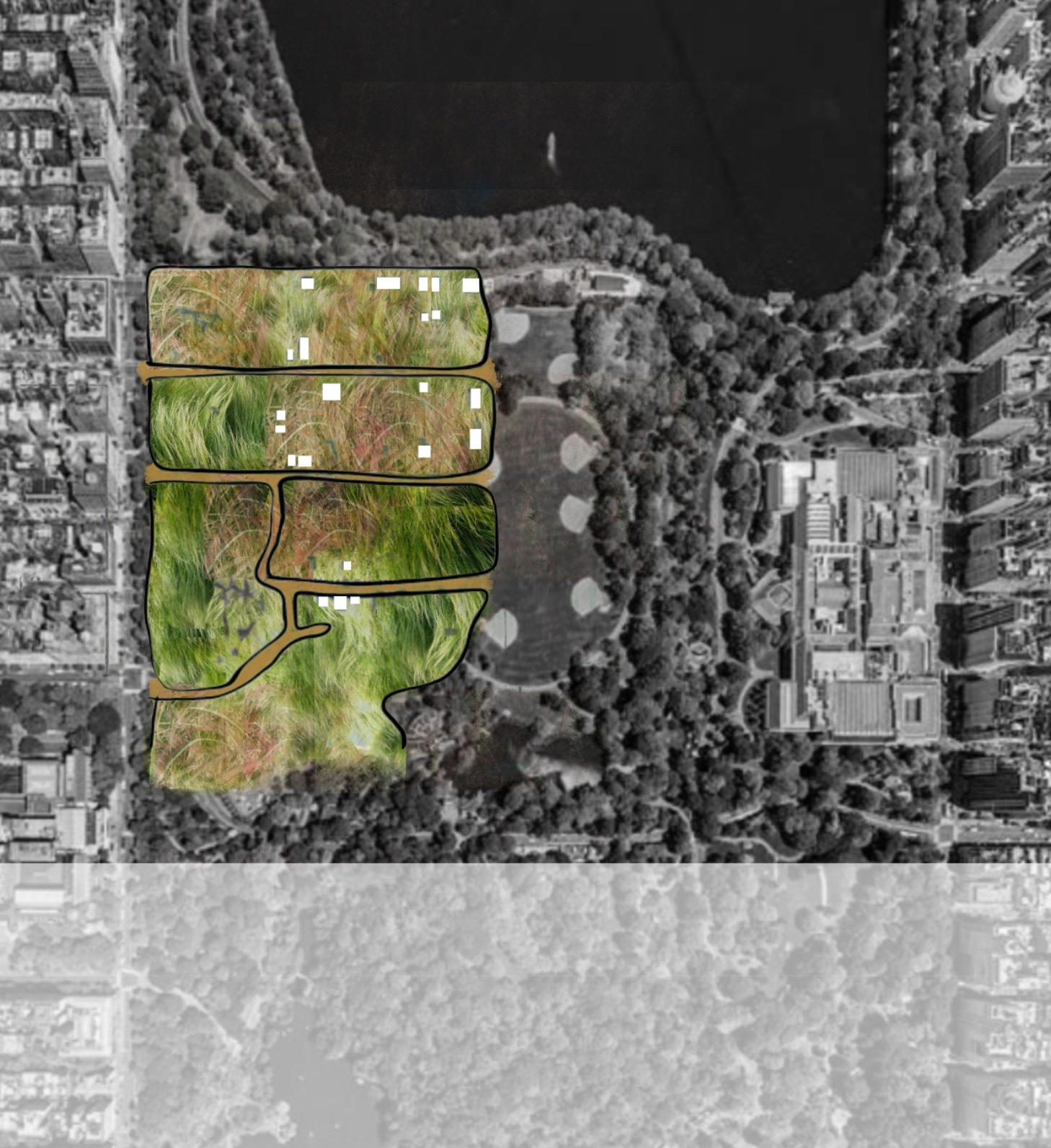

If you are unfamiliar with Seneca Village, here is a quick recap: Seneca Village was the first prominent community of African American property owners in Manhattan, with a population of roughly 225 people, two-thirds of which were the first freed African Americans. The Village, existing between 1825 and 1857, stretched from 82nd to 89th street in Upper Westside, was then taken from its residents through eminent domain to create Central Park as we know and love today.

As explained by the Central Park Conservancy, “to a modern-day visitor, the site of Seneca Village resembles much of the surrounding Park, with rolling hills, rock outcrops, and playgrounds. But what many do not realize is that this area near the Park’s West 85th Street entrance has an important history. During the first half of the 19th century, it was home to Seneca Village, a community of predominantly African-Americans, many of whom owned property.” What stands out to me most about this statement is the identification that the site of Seneca Village and its significant and rich history, yet it resembles much of the surround park, as though it’s just another few acres. In 2019, as a result of activism by nonprofit organizations to recognize Seneca Village, the Conservancy installed a temporary sign that “shares the decades of research about Seneca Village and allows visitors to discover the community in the places where they actually lived.”

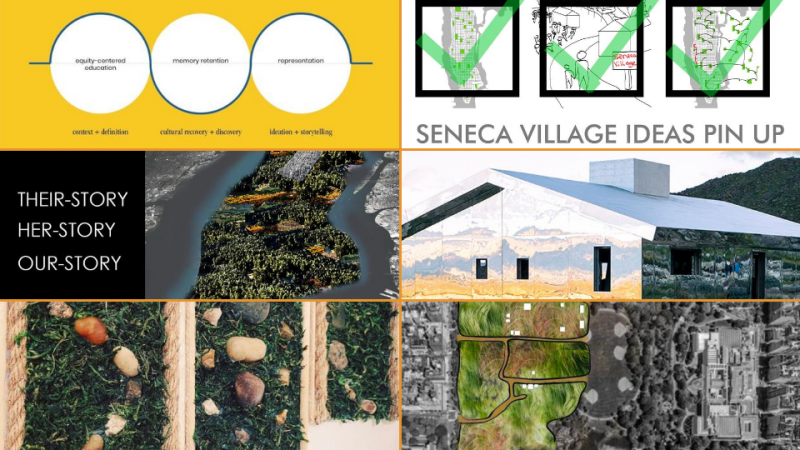

IDEAS PINUP

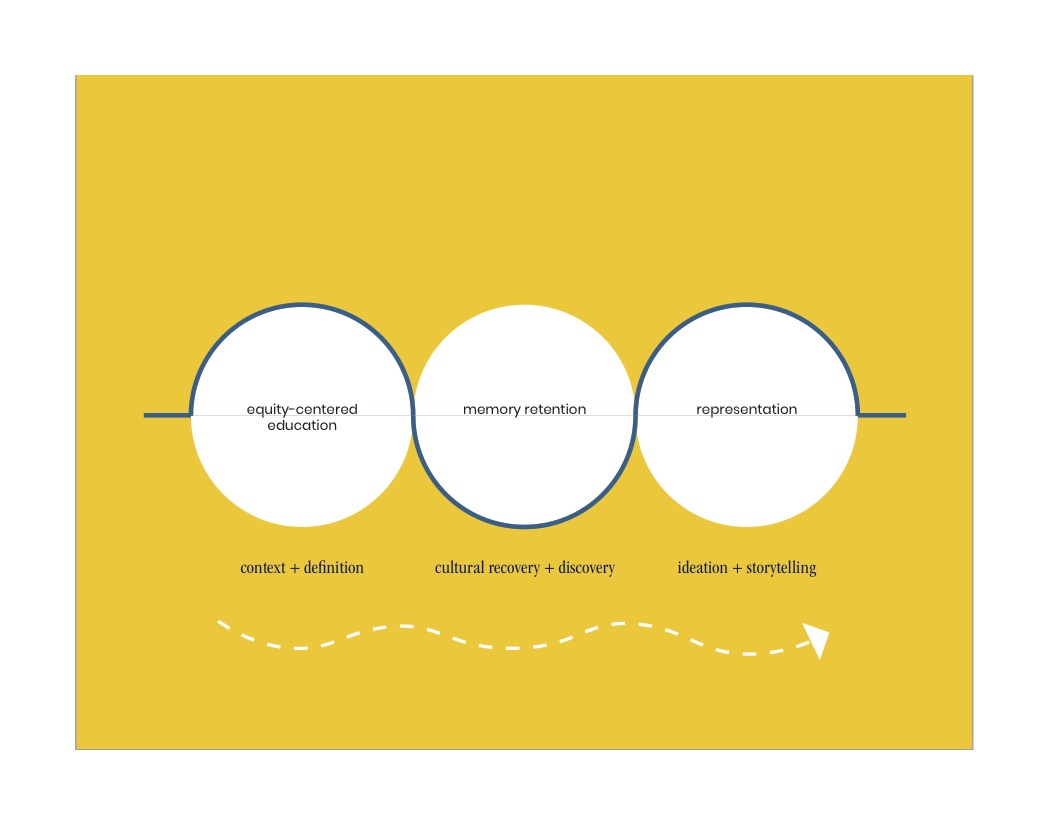

The Black Lives Matter movement taught us quickly that we must continue to learn and unlearn in order to make progress and create a better and more just future. I believe the same can and should be applied to our design thinking and approach to understand and designing sites. To be an active participant in that process within our field, the Ideas Pinup: Seneca Village invited everyone to come up with design solutions to what is a design problem. Seneca Village could have been saved, African Americans who owned land in the Village could have been thriving in their lands for the decades to come. Even now, only a few years ago when areas within original Seneca Village boundary went through a redesign, it should have begun to at least take active storytelling into consideration, but unfortunately it didn’t.

To take words into actions, landscape designers and architects submitted design ideas and elaborations exploring ways that the Park could have been designed differently, how to redesign it as a healing space, complete reconfiguration of the Park, understanding public memory, and series of installations to remind visitors of the Village and its stories. Here is a look into the diverse ideas that expand on how we could have or can still honor Seneca Village through design thinking and active participation, please see full submissions by all participants here.

Design is a powerful tool, and landscape architecture has the power to make a difference, whether it’s preserving the stories and dignity of those who have come before us, or making better decisions moving forward. I hope this post, the conversation on Seneca Village, or the Ideas Pinup has ignited your interest in beginning and continuing this discussion, and similar discussions, with your designer colleagues and friends. If you are within academia, I encourage you, if you are not already, to begin these conversations in classrooms and studios, teach everything about Central Park, not just design ideologies. Tell the entire story, not just the pretty parts.

*In collaboration with Land8, we will be hosting an online call to provide a platform for the designers to elaborate on their ideas (like a pinup!) – VIEW RECORDING >

**With expressed interest, the Ideas Pinup Seneca Village is now open indefinitely! Please send your ideas whenever you find inspiration, and they will be added to the permanent gallery that I hope will continue to be a starting point of conversations in our classrooms, offices, and discussions

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured