Water shortages are becoming more and more an ever evident occurrence in our daily lives in the western world. While underdeveloped countries have dealt with the extreme effects of droughts for decades, the Western world has escaped much of the hardship through quick fix solutions. These include damming rivers, piping water halfway across the landscape and installing more and more irrigation. Something’s gotta’ give, sooner or later. The current problem in many cities and countries worldwide is declining precipitation rates, a problem that is exacerbated by aging infrastructure. This is most evident in London, where a hose pipe ban is currently in place. The situation is so dire at the moment that the ban is being touted to be in place from now until early 2013. Other problems caused by a combination of intensive agricultural practices and climate change include soil desalinization and desertification. But worryingly, 40% of the world’s population currently faces water shortages, with water supply expected to drop by 30% per person by 2030.

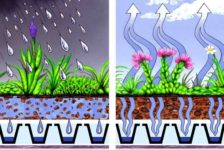

How does Landscape Architecture fit into all of this? So what’s the problem and what does this have to do with landscape architecture? Well, we are the ones who specify the lawns and planting schemes that need supplementary irrigation and fertilizers to stay in pristine condition aren’t we? A worrying fact is that there is 3 times the amount of irrigated lawns then there is irrigated corn in the US, considering there is no output from lawns, only wasted input. Irrigation and fertilizer practices are an oxymoron of a solution really, considering fertilizers raise the salinity of soil and require MORE water to dilute them and prevent a build-up of toxic levels. But the overall point that defeats irrigation and fertilizer practices is that they are not sustainable, I mean, if a plant can’t survive in a location by its own means, surely you have chosen the wrong plant for the wrong place? With the realization dawning on our profession that water will not always be abundant in our landscapes, changes in practice are necessary. Solutions? First off, right plant, right place. Better education on plant choices in our profession is needed. Native plants have an apparent advantage and are well adapted to a site’s climate, but are not always the solution. Other factors must be taken into account, such as on site micro-climates and especially in urban environments, the “Heat Island Effect”. This is where drought tolerant plants come in, native is preferred, but we mustn’t restrict ourselves. It is better to be criticized for using an exotic plant and for it to thrive than to use a native plant for “greenwashing” purposes and have it fail. This will only backfire and give bad PR for native plant strategies. Second, replacing fertilizers products with more sustainable practices. To avoid causing soil salinization and hence needing more water, we, as landscape architects, should employ techniques such as companion planting. Soil binders, nitrogen fixers, green manure and pest repelling plants can ensure that a scheme has its required nutrients and soil structure. Thirdly, if irrigation is essential, we must look at using water more efficiently. This includes using grey water from residential and commercial premises for irrigation. Rainwater harvesting is also another option, with the added benefit of managing all stormwater on site. Using potable water is wasteful, while the other options help lower costs and relive pressure on infrastructure. Practices such as these are vital when you consider that while only 3% of the Earth’s water is suitable for irrigation & consumption, only 0.03% of this available for use by humans. And finally, employing a planting philosophy that uses water efficiently and conserves it, otherwise known as Xeriscaping. A practice defined in the early 80’s in response to droughts in the American mid west, xeriscaping uses a mixture of native and drought tolerant plants and contoured landscapes to use water efficiently. It is a practice that is gaining acceptance worldwide and will become a vital element of present and future landscapes. Recommended reading: Dry-Land Gardening: A Xeriscaping Guide for Dry-Summer, Cold-Winter ClimatesThe question remains, what can landscape architects really do? BREEAM and sustainable landscape practices are great and everything, but they’re not going to reverse the problem of water shortages. While this is true, landscape architecture still has a duty as a profession to play its (vital) part in a sustainable world that is adapting to a constantly changing, emergent environment

Article written by Joe Clancy Featured image: Ev Thomas / shutterstock.com

This article was originally submitted to Landscape Architects Network

Published in Blog