Europe’s Last Plague

May 25, 1720. The Grand Saint-Antoine, a three-masted French merchant ship, sails into the port of Marseille on the southern coast of France. Its journey has been troubled: nine passengers have died since departing from Lebanon two months earlier. Following protocols designed to prevent disease outbreaks, Marseille’s health bureau orders the ship, its passengers, and its cargo of precious silks to be held in quarantine on a nearby island. In a notable breach of protocol, however, the bureau allows the early transfer of the cargo to the mainland—a fatal decision, made under pressure from silk merchants who want to bring the goods quickly to market.

June 20, 1720. A woman dies abruptly in downtown Marseille, an area of narrow streets and dense housing. She is the first victim of community transmission of the Great Plague of Marseille, a pandemic of bubonic plague caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. By the middle of August, more than one thousand individuals are dying every day. By now, the wealthiest have fled, along with many government officials. Bodies are left on the streets, and prisoners are forced to carry them toward mass graves.

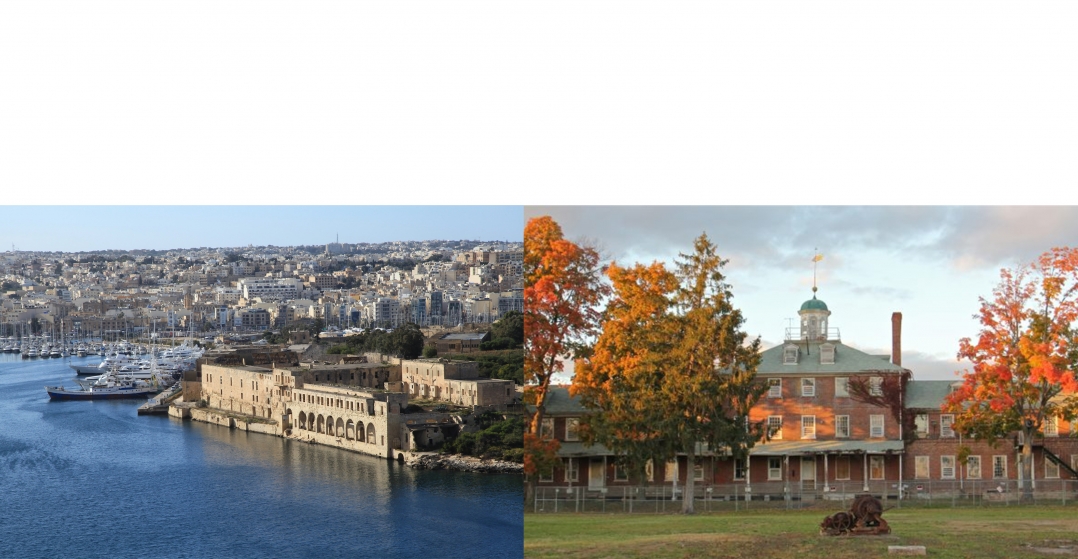

March 1721. Fearing the spread of the pandemic, King Louis XV sends thirty thousand soldiers to enforce a strict quarantine over the entire region. Fifty miles north of Marseille, he requisitions local villagers to build a seventeen-mile-long drystone wall to prevent escape. Despite these efforts, the plague kills one hundred thousand people over the course of two years: fifty thousand in Marseille—half the city’s population—and another fifty thousand in the surrounding provinces. It is Europe’s last major outbreak of plague.

The legacy of the plague in Marseille is complicated. Street names and public sculptures honor the dead. Every year the Basilica of the Sacred Heart honors the anniversary of a promise made by the city council in 1722 to hold a special mass every year, in perpetuity, if the plague spared the city. And the foundations of the drystone wall still stand to the north of the city, now branded the mur de la peste—the “plague wall”—by regional hiking guides.

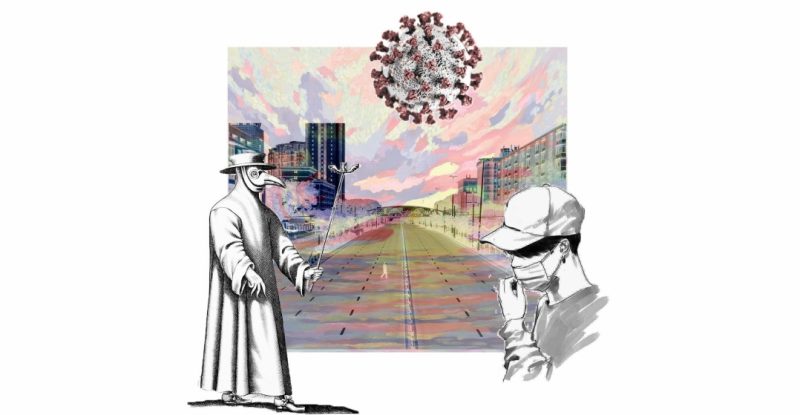

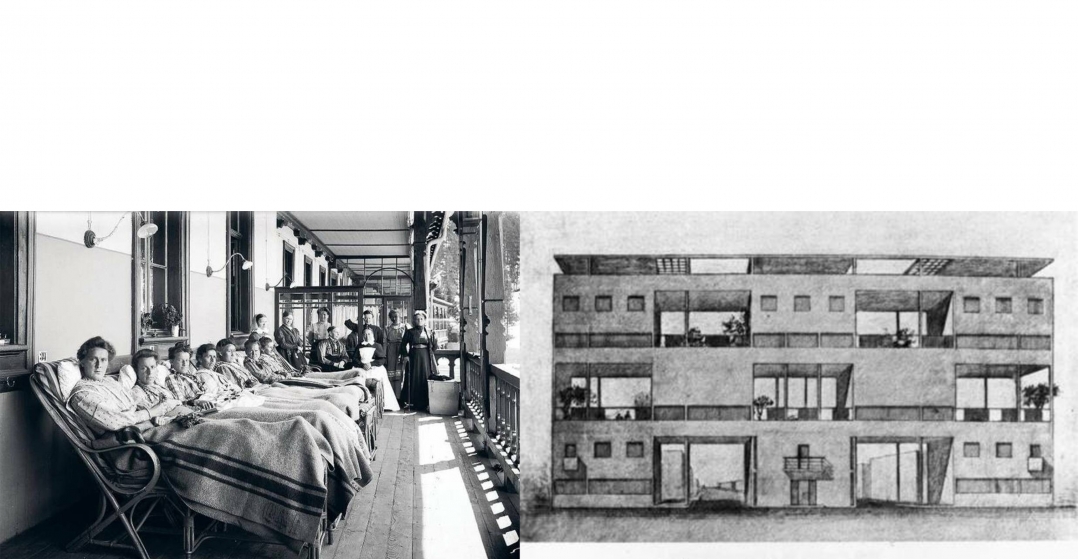

The wall and the ceremony remain as traces of a society’s attempts to restructure its relations with its environment and its diseases: the church service through an act of imagination, and the wall through the reorganization of space. Yet they betray the fact that Marseille’s greatest trauma never prompted a comprehensive reevaluation of its urban fabric: no Haussmann-like boulevards to bring fresh air and water into the dense urban core; no new sanitary practices or governance strategies; just business as usual, but with a new annual mass. The story of Marseille helps us interrogate our present situation. Beyond memorials and rhetoric, what will be the legacy of COVID-19? How will it restructure our societal narratives and the ways we manage space? How will the quality of our attention now, in the midst of crisis, shape this future?

Above, stained glass window, in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Marseille, depicting the city council’s vow to hold annual masses, in perpetuity, in hopes of being spared from the plague. Below, the mur de la peste—the “plague wall” of Louis XV.

Stories of Disease, Stories of Culture

Pandemics are ancient—as old as human culture itself. Wherever they have struck, they have challenged humans to reevaluate their relations to their environment—as well as the cultural myths that underly these relations. In the face of crisis, these myths—the stories we tell about ourselves—can act as foundations for resilience just as they can constitute sources of vulnerability.

At the “Designing the Green New Deal” conference in Philadelphia in the fall of 2019, the writer and activist Julian Brave NoiseCat spoke of the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—a five-hundred-year-old constitution that has guided its people through settler colonialism, military invasion, pandemics, and the systematic government kidnapping and reeducation of children. “Cultures are really just manuals for how we’re going to do all these things together as people. If the Haudenosaunee can maintain their Great Law against an apocalypse, against genocide, I do believe that culture, and the stories that we tell about ourselves, and the words that we use to tell these stories, are some of the most powerful things that we have.” As we sit in quarantine, it’s worth asking what COVID-19 says about our ways of inhabiting the planet—and how our stories might change in response. We wouldn’t be the first to do so: artists have long used plagues to amplify questions about what it means to be human.

In Albert Camus’s The Plague (1947), an Algerian city is walled off following the outbreak of plague. When the disease abates, the city celebrates, but the protagonist, a doctor, knows that the plague will eventually come back, because “everyone has it inside himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune.” More than a simple disease, the plague is a reminder of the fragility of the human condition.

In Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), a shepherd witnesses the progressive falling apart of human civilization due to plague. Cities, art, and society all disintegrate, leaving the shepherd to roam alone through an emptied landscape. Shelley’s is a pessimistic plague, insisting that humans are not the center of the universe, that pride comes before the fall.

In Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842), groups of nobles flee the cities—to a rural villa and a gothic abbey, respectively—to avoid disease and pass the time in celebration. Bocaccio’s youths use their quarantine as an opportunity to inspire and amuse each other with tales of humanity; Poe’s bored aristocrats come to a bloody end among the decadent trappings of their entertainment.

In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a group of educated young friends pursues an aristocratic vampire landlord through a complex network of cities, ships, trains, and properties. Stoker’s novel, and especially F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film adaptation Nosferatu, use vampirism and disease to speak of the fear of the Other—especially the Easterner—and of the spread of contagion through an increasingly globalized infrastructure.

Each of these stories imagines disease through specific spatial contexts. For Camus, walls keep the plague in; for Poe and Bocaccio, they hold it out. Shelley’s shepherd is left to wander the ruins of urban and rural life, whereas Stoker’s young professionals travel through a highly connected urban-rural landscape. These stories of disease are also stories of space, of how its management—through walls, public squares, roads, and countryside—enables life and death.

In 1721, the French painter Michel Serre depicted a scene from the Great Plague of Marseille. Dreary clouds loom over buildings that appear empty and lifeless. The city square, the heart of the public realm, is strewn with bodies, the distinction between living and dead blurred. At the center of this maelstrom, sitting calmly on a rearing horse, a city official directs the removal of corpses, a modicum of order in a portrait of devastation.

J. Robert (Bob) Wainner

I have a MAJOR problem with this entire article! The first problem is that this author lives in “Berkley, California”…..and my guess is this person’s political beliefs are extremely “Liberal”. So, you have to keep this in mind when reading this article.

All this Liberal talk about “We will have to establish a NEW Normal”…we can never go back to the way things were, before the COVID-19 virus arrived. I wish to remind this author, there is a LOT of evidence that the COVID-19 virus was “man-made” by CHINA in a LAB. This virus “might” have been an accident…but, it’s very clear that CHINA decided to weaponize it against both Europe & the U.S. people and economies!

Liberal Politicians would love to keep Americans scared, people kept in their homes, businesses closed….this is a form of CONTROL and OPPRESSION over the people. And, in this Presidential Election Year…..this is a Liberal/Democratic Party “agenda” in an attempt to destroy America’s good economy….in hopes of removing President Trump from the White House.

America is the Land of FREEDOM and LIBERTIES……If you take those away from us, AMERICA ceases to exist.

It’s almost humorous to see an article like this one coming from a California resident. Why doesn’t California focus a bit more on ALL of their problems…..out of control smog & air pollution; methods to conserve Water resources; coming up with ways to do a much better job with Forestry & Wildfire Management; resolve the out of control homelessness throughout the State; Elect Officials who could lower State Income Taxes and put those taxes to better use for the citizens of The State of California…..to name just a few of California’s many self-inflicted problems. I was actually born in Southern California and it seriously saddens me to see how California has been so poorly governed over the past 50 years…..and the State is still going down hill fast!

J. Robert (Bob) Wainner

J. Robert (Bob) Wainner

FELIX………I DISAGREE with you. NO, everything is NOT “Politics”. That was just Liberal Propaganda that was fed to you at CAL BERKLEY!!!

J. Robert (Bob) Wainner