By Corey Dodd and Tarana Hafiz

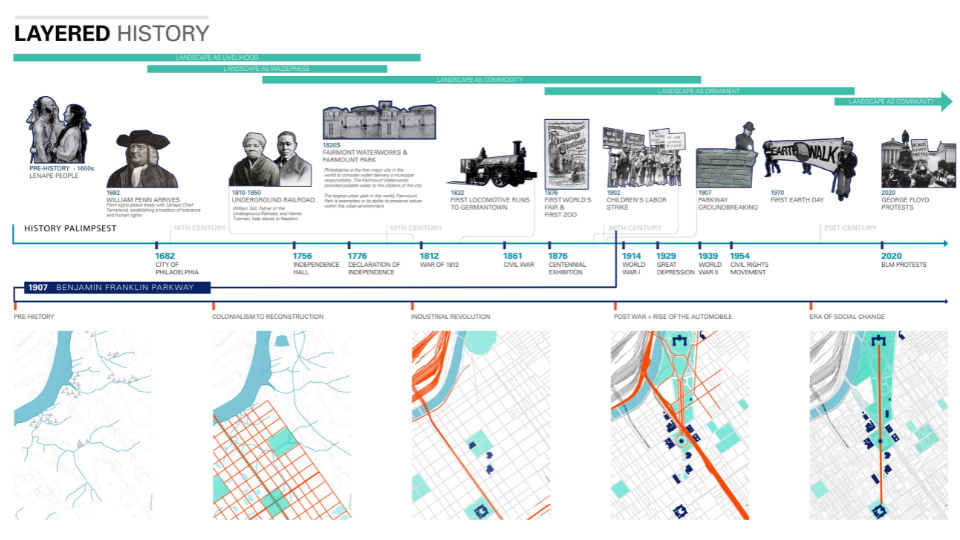

In the fall of 2021, the City of Philadelphia embarked on a project to Reimagine Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Along with other iconic, historic cities around the world, Philadelphia is following suit with reinvestment in the public realm, featuring a more pedestrian-friendly approach to the historic corridor. Today the Parkway serves as the city’s hub for cultural institutions, a venue for large- and small-scale events, a destination for exercise, play, and social activities, and as a promenade for peaceful civic demonstration. A goal of the project includes honoring the historic design intent of the Parkway which stems from the City Beautiful Movement that claimed design could not be separated from social issues and should help facilitate civic pride and engagement. Also crucial to the Parkway’s future legacy is celebrating Philadelphia’s cultural richness and diversity, and embodying the hopes and dreams of its citizens by weaving education, civic assembly and recreation in an inviting, safe space.

The reimagined Parkway will be repositioned from one that is a ceremonial thoroughfare made for the automobile, to one that reflects the hearts and voices of all Philadelphians. The community holds an integral role in the process to build a more “people-centric” space. This is an opportunity to address tough questions, and the Parkway, if designed right, has the potential to be a space for escape and expression when faced with issues of our current socioeconomic climate – an ongoing pandemic, racial and civic injustices, and challenges such as homelessness and violence. This project represents a new light and an important time where, together, we are co-creating what a free and fair public space means for Philadelphia and how it can be optimized for all people.

Image: Design Workshop

As with any major city, Philadelphia has continued to evolve since the inception of this incredible example of civic art in the Beaux-Arts style and serves a far more diverse and denser population than when it existed in 1917. Recent urbanization trends challenge the design of this grand civic space. The expansive linear streets once adept for guiding residents and visitors between the museums, artworks, and railroad stations that lined the Parkway are now dominated by commuter motorists. These multiple-lane freeways fragment the public realm by dissolving spatial definition and creating challenges for accessing the boulevard and its institutions as a pedestrian. In our conversations with the people of Philadelphia, one thing is clear – the foundation of the vision is to build a destination for people, not vehicles. By making the Parkway a place to come into, not through, we can reestablish connecting the public to the city’s immense playground.

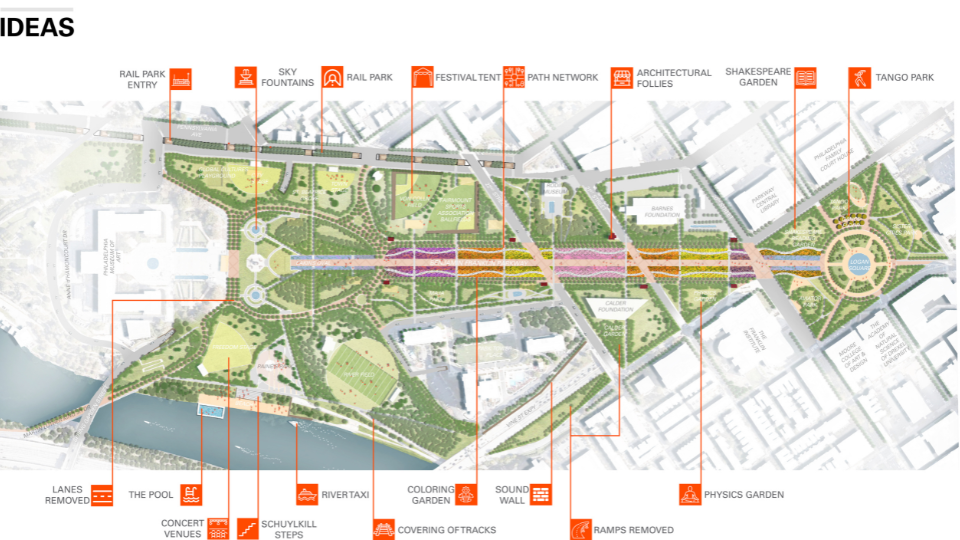

Currently, the Parkway is characterized by its edges; the edges are where it is safe to stroll or roll your way between institutions on shaded walkways. In the effort to make the parkway a holistically welcoming place and a green transect that allows a pedestrian to experience moments from Love Park to the Oval without physical or behavioral impediments, there is a need to turn the park inside out, allowing the character to expand toward the edge. Continued opportunities for public art, creation of nodes and the implementation of pocket parks or plazas will serve as connective tissues between institutions and neighborhoods. The provision of an informational center to keep users up to date on the happenings of the Parkway and direct passersby have all been reoccurring themes for amenities defined by stakeholders. The result could strengthen the central arms of the boulevard and stretch to the park’s edges. The Penn Avenue Initiative in Washington D.C., Passeig De Sant Joan Boulevard in Barcelona, and Times Square in New York are examples of public spaces that have reintroduced the notion of energizing streets by right-sizing them for people. This project provides a chance to not only learn from such precedents but truly embody the idea of a “democratic landscape” through design elements such as activity zones, symbolic art, defacto stages, widened sidewalks, welcoming gardens, and assembly spaces; essentially programs that cater to a variety of people and their backgrounds.

Image: Design Workshop

Paths and plantings are the backbones of the park, but people are its lifeblood. The people who regularly visit this public green space come for varying reasons and their presence is a welcoming attraction to others. While special events are an important aspect of the park, other programs will be developed to provide a balanced and continuous attraction to visitors, strengthening the park’s mission. Opportunities for future partnerships exist with neighborhood schools for youth engagement in public art exhibitions and outdoor learning labs. For example, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society could lead rotating cohorts to engage community members in learning and providing support to maintain Parkway plantings or a community garden space.

Reimagining Benjamin Franklin Parkway provides the prospect to face topics of healing, progress, and innovation. This can only be achieved by going directly to the community and learning from the untold stories and perspectives that will break up the monotony of this largely whitewashed history and make the historically Eurocentric space a place for all voices from diverse backgrounds to be represented. This is not just about a physical place, but a space in time – to catalyze change and have difficult, yet productive conversations around social engagement and community mobilization that speaks to a diversity of patrons. As we move through the design process, the hope is to reach the most marginalized communities of the city, constituents who rarely have a seat at the table during such a planning endeavor and co-create ideas with everyone. Creative engagement methods such as “meetings-in-a-box,” mapping techniques using Safegraph data that helps us better understand neighborhoods under-reached by the Parkway’s current programming, or social media campaigns that provide a platform for discussion and debate around a people-centric Parkway. These are all ways to build a plan that is reflective of the dreams and aspirations of Philadelphians- youth and seniors, BIPOC and white, abled and those living with a disability, advantaged and the disenfranchised.

Image: Design Workshop

Engaging citizens who currently use the Parkway in addition to those who do not but wish to use the space in the planning process is the only way to ensure the long-term sustainability of the park as an inviting, educational and economically viable place. In doing so, offerings that truly meet the desires and needs of residents and visitors who contribute to the vitality of the city will be incorporated into the reimagined design- from safe bike routes to the Schuylkill River, to pop-up kiosks for food and beverage, and multipurpose community hubs for youth activities. This iteration of the design process that relies on public inclusion is reflective of both the evolution of Philadelphia’s demographics since the park’s inception and the evolution of the process of designing public spaces. We are beyond the times when a select few determined when, how, and where changes to the spaces we all wish to enjoy and utilize are made.

This project will impact similar public realm projects with historical significance across the nation by demonstrating that success can be found in maintaining the essence of original design intent while addressing modern needs for accessibility and play. True value of a public space is found when all citizens can identify their likeness in a network of civic spaces – whether that be visually through art, through accommodations for information sharing, or in something as simple as a planting that reminds them of a family garden. These multi-faceted roles of grand pedestrian parkways are vital to the health of cities like Philadelphia because they cultivate an engaged citizenry. The ability of the Parkway to spark emotions and create memories has and will continue to be at the heart of Philadelphia’s beloved park.

—

Corey Dodd is a landscape designer based in the Raleigh studio of Design Workshop. His work centers on cultivating contextually sensitive environments that contribute to the overall well-being of communities by empowering people as placekeepers and placemakers in identifying the inherently special qualities of their public spaces through historical and cultural literacy.

Corey Dodd is a landscape designer based in the Raleigh studio of Design Workshop. His work centers on cultivating contextually sensitive environments that contribute to the overall well-being of communities by empowering people as placekeepers and placemakers in identifying the inherently special qualities of their public spaces through historical and cultural literacy.

Tarana Hafiz is a New York City native and Houston-based urban designer/planner with Design Workshop. She specializes in developing equitable communities, addressing issues faced within public spaces, and integrating outreach to garner support for impactful design.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured