10 search results for "daylighting"

If you didn't find what you were looking for try searching again.

Four Reasons Why La Rosa Daylighting Project is a Design all Cities Must Have

Article by Joanna Łaska – La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting Project, by Boffa Miskell, in Auckland, New Zealand. Auckland’s La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting project by Boffa Miskell is an outstanding example of design work that can bring us closer to nature. It embodies the very nature of ecology and sustainability, and is one of these projects that grasps ecological, cultural, and community values and brings them all together to create a space for people to enjoy and learn from.

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

Daylighting Project

1. Hard Work Always Pays Off

The La Rosa Stream project didn’t just jump from the design page to reality. It required a lot of hard work from the designers and contractors who met challenges involving design, consent, and construction. The project required the removal of 5,000 cubic meters of natural clay. The next step involved bringing up 200 meters of watercourse that had previously flowed through underground 100mm- to 1,350mm-diameter pipes – that meant that the contractors had to remove 180 meters of underground pipes. Bringing the water up was just a small part of the whole project: Once the water was up, it had to be given a natural look.

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

2. Details Make the Difference

The La Rosa project is an exquisite example of thoughtful landscape planning and superb detailing. Everything about this project seems to be carefully thought out: Every single stone placement seems to be planned, and that is what makes this design a role model for all landscape architects – for those who are less experienced and for those who have already made hundreds of projects in their career.

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

3. The Most Liveable City in the World

La Rosa is the first-ever dedicated stream daylighting project in Auckland. It is part of the city mayor’s 100 projects to make Auckland “the most liveable city in the world”. It was designed to not only restore the natural stream, but also to reuse and embody the energy in that place. The project is mostly made of natural and reused elements. However, the project also has another purpose: to bring the Auckland community together.

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

4. Learning from Nature

Despite the construction of the project being an expensive exercise, the hard work and investment will definitely pay off in the long term, as having a natural stream rather than a huge amount of underground pipes that need upgrading and maintenance is always a financial benefit. However, the project’s success is not just being calculated in numbers, but in the development of knowledge in hydrology and ecology.

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting. Photo credit: Boffa Miskell

Full Project Credits For La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting Project:

Project Name: La Rosa Reserve Stream Daylighting Design: Boffa Miskell Location: Auckland, New Zealand Date of Completion: 2012 Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network

Article by Joanna Łaska

10 Ways to Increase Biodiversity in Any Design

What is the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about biodiverse ecosystems? Probably the hard-paved, concrete, urban environment is not what you have in mind. Though cities are dominated by one species, (which I assume we are both representatives of), they are ecosystems full of opportunities. Urban environments are compositions of prospects and threats. Seizing those opportunities demands from us a new understanding of environmental protection.

Some people might ask why we should care about urban ecology if there is a vast wilderness out there. Yet studies on urban biodiversity show that it is a cause worth fighting for. If you want to know how important urban biodiversity really is, check it out here.

In this article, we summarize 10 methods that will help you create more biodiverse and environment-friendly designs.

Methods for Increasing Biodiversity in Any Design:

1. Protect, restore, mimic

This is the first and most important rule. Get to know local ecology and protect it. If you think there is nothing to protect, look at it again, and look closer. If it is an already degraded area, understand its past and check if you can restore part of what was there before. Drawing inspiration from the past will indicate what plant species to use in your design, and any systems that need renovating, such as daylighting rivers.

2. Use native species

Some may argue that the urban environment is so drastically different, that some native species may not flourish in it; it is always worth investigating. If you aim to increase biodiversity in both the plant and animal kingdoms, native species will support the richest wildlife. And always remember to avoid invasive species or any that may become invasive in your design area.

Flower meadows in the City of Cracow, Poland by Fundacja Łąka

3. Create layers

This method is only applicable in climates where layers are the natural order of growing. Although traditional lawns are one of the most popular landcover approaches, they do not provide much of a habitat for wildlife. More naturalistic planting, like flower meadows, can support butterflies, and bees. Taller tussocky grass may become home to animals that are not satisfied with turfgrass. This meta-analysis study from Germany has demonstrated that biotic factors, like vegetation structure, are extremely significant in supporting wildlife. Here you can check other arguments on whether to banish lawns or not.

4. Diversify

Ph. D Sofie Pelsmakers in her book ”The environmental design pocketbook” suggests, that to avoid disease, pests, and to support biodiversity, you should select plants from a maximum of 30% of the same family, 10% of the same genus, and 20% of the same species. If you design a larger area, you should also follow the suggestion of Tan Puay Yok from the book “Nature, Place & People: Forging Connections Through Neighbourhood Landscape Design”, to diversify types of ecosystems.

5. Do not gild the lily

Every space in the design area should be carefully thought through. However, sometimes it might be advantageous to leave a fragment for Mother Nature to design. Natural succession and preservation of natural vegetation are the most failsafe ways to incorporate all the methods outlined above to increase biodiversity.

Central Park, Manhattan, New York City by Ajay Suresh CC2.0

6. Offer food, shelter, and nesting place

We may have an influence over-designed vegetation, yet controlling other kingdoms such as invertebrates, mammals, and birds, is not so easy. Nevertheless, providing food, shelter and nesting places might be our best shot. Always support existing habitats with a respectful approach. Different species might need different methods. For example, a high green roof may attract butterflies but be inadequate for bees. House sparrows appreciate nesting 2m above the ground, while peregrine falcons need nesting sites to be more than 20m high, preferably with a good view for pigeon-pray.

Puerto de Mogan, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands by Giuseppe Milo CC2.0

7. Minimise light and noise pollution

Those two can cause psychological stress in humans, as well as in other animals. Nobody likes to live in a hectic area. Therefore, to not repel biodiverse wildlife, keep light away from their resting spots, like ponds, tall trees, and hedges. According to Ph. D Sofie Pelsmakers, light below 3lux at the ground, ideally 1 lux, is required. Avoid white and blue wavelengths.

8. Build corridors

If you followed all the previous tips, you have now quite a decent potential habitat! Now is the moment to allow animals to get to it. According to the previously mentioned meta-analysis study connectivity is one of the most significant factors influencing biodiversity. Connectivity in the matrix is crucial because otherwise, you risk fragmentation and the creation of an ‘ecological sink’ for animals to die in, without enough genetic diversity to sustain subsequent generations.

If a true corridor is not possible, try steppingstones. They might not be as successful as corridors, but they may be a good compromise of cost and ecology. A nice idea for this approach might be pocket parks.

Boston glass buildings by Xavier Häpe CC2.0

9. Reduce threats

Assuming you already considered providing shelters, another aim could be to reduce bird mortality. Birds often fly directly into the glass as they confuse reflections with reality or try to fly through the building. A lot of them die. If you want to avoid this pointless animal death, you can avoid planting new trees near the large glass surfaces and corner windows. Probably the best approach would be to not use big surfaces at all in the first 23m from the ground or use glass safe for birds. You can find other guidelines and information here.

10. Consider management

According to a recent international report, there are four management activities that you should avoid. The report reinforces the point made in method No. 3 above, that short turfgrass lawns and the simplification of habitat structure can have detrimental effects on biodiversity. Another interesting example is not being too tidy. One Australian example from 2010, demonstrated that just leaving leaf litter increased bird species richness by more than 30%. Hedgehogs and other small animals would also appreciate this technique. Lastly, it is important to consider pesticide and herbicide applications, as they usually cannot recognize “good living beings” from “bad living beings” and indiscriminately kill. By design, they reduce species-richness of plants, therefore repel animals.

Time to act on biodiversity in design

Biodiversity is reducing across the planet. It is neither the time nor the place to ignore biodiversity in our designs. Taking species diversity into account might look challenging, but even these simple methods outlined above will help. Firstly, respect what is there. Then consider diverse, native planting, that will attract animals. Then make your designed habitats as hospitable as possible with prescriptive maintenance.

Are there any other methods to increase biodiversity you would like to share with us?

—

Feature Image: Vancouver Land Bridge (Confluence Project)

Article by Agnieszka Nowacka

How Landscape Architecture Mitigates the Urban Heat Island Effect

Global temperatures are rising. This is especially felt in urban areas due to the urban heat island (UHI) effect, where temperatures can be 10oF (5.5oC) higher than the surrounding countryside. This phenomenon is due to several factors that combine to alter the local microclimate of an urban area. However, several techniques can be employed by landscape architects to help combat the local rise in temperatures, saving money, reducing global warming, and making a more pleasant environment to live and work.

In this article, we look at what the urban heat island effect is and what landscape architects can do to combat it.

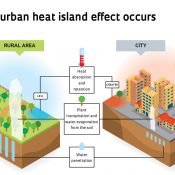

What is the Urban Heat Island Effect?

Objects of different colours reflect varying amounts of light. Surfaces with a greater albedo (or lighter colour) reflect more of the sun’s energy. Darker objects tend to absorb more radiation and therefore heat up more quickly. As our cities are usually made of darker materials like concrete and asphalt, they absorb comparatively more energy from the sun and therefore heat up more quickly than the surrounding, lighter coloured and vegetated countryside.

Cities tend to drain surface water quickly into sewers, where it is trapped, and cannot evaporate as easily. In rural areas groundwater drains through the soil and is transpired by plants. The evaporation of water in rural areas adds a cooling effect to the local climate.

Finally, things like air conditioning and vehicles add small amounts of heat to the air in cities, contributing to the UHI effect.

Mitigating the Heat Island Effect

There are various ways in which the UHI effect can be mitigated through technology and the use of landscape interventions.

Technology that Reduces the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

Reflective surfaces

One way to decrease the amount of the sun’s energy that is absorbed by a city is to use lighter coloured materials. However, light colours also create glare, which is not only annoying for city residents but can cause problems for drivers. One solution is to use lighter coloured paints on higher roofs. These are known as ‘cool roofs.’ Another technological solution is to use special reflective paints that absorb visible light while reflecting invisible light. As these paints do not reflect visible light they can be darker in colour. However, the extent to which reflecting only infrared light has on the UHI effect is still under debate, with some experts claiming that the benefits are minimal.

White roof and skylights on Las Vegas, Nev. Walmart_Walmart corp. CC2.0

-

Solar panels

Another approach is to actively use the radiation from the sun to generate electricity. Photovoltaic panels can be used to provide shade to a building, preventing the thermal mass of the building heating up, and radiating its stored heat at night.

Green Ways to Reduce the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

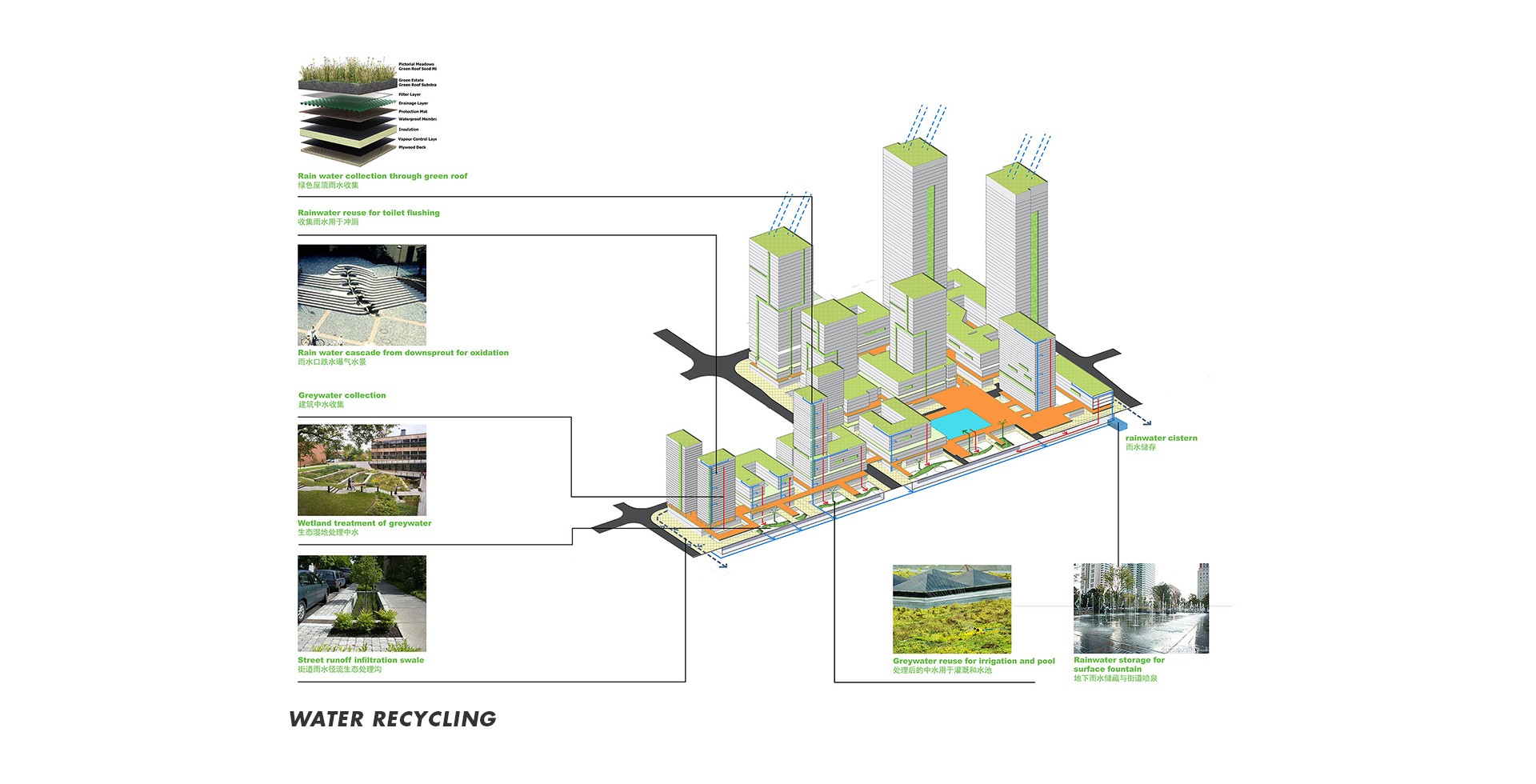

Green roofs and walls.

The benefits of green roofs on stormwater management, biodiversity, habitat creation, and building insulation are well documented. However, they also have an important role to play in mitigating the UHI effect. Not only does the higher albedo of the plants reflect more of the sun’s energy, but as the plants transpire the surrounding ambient temperature of the building is lowered through evaporative cooling. Green walls have similar effects in reflecting more light and evaporating moisture.

-

Permeable surfaces

Tests have shown that while wet, a permeable paving system of interlocking concrete blocks performed localised cooling better than impermeable surfaces. For permeable surfaces to have a significant effect on the UHI effect it is important to note that there should be regular rainfall to evaporate. Also, the depth of the water table below the surface also impacts upon the permeable paving’s cooling efficiency.

-

Green parking lots

Vegetated surfaces like green parking lots combine many of the benefits of green roofs and permeable paving. All too often parking lots are made of dark coloured, impermeable asphalt. However, by using a material like concrete Grasscrete, or porous plastic paving units, the cooling benefits of vegetation and permeability can be exploited, while still maintaining a degree of usability.

-

Urban Trees

There are several ways in which trees help in mitigating the UHI effect in a city. As tree leaves are usually lighter in colour than the surrounding urban fabric they reflect more light. Trees also affect their local atmosphere by transpiring. A large oak tree can transpire as much as 40,000 gallons (150,000 litres) per year. Street trees are particularly good at shading buildings and sidewalks, effectively filtering the amount of radiation that reaches the lower albedo surfaces.

Harvesting the Power of Water to Reduce the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

Incorporating water into the landscape

As bodies of water evaporate, they cool their environment. By increasing the surface area of any water feature in the urban landscape, the amount of evaporation is maximised. Therefore, there is a strong argument for including water in any urban landscape, whether it be a lake, pond, or daylighting an old stream that has been covered over, such as the La Rosa Daylighting Project in Auckland, New Zealand.

-

Rainwater harvesting

One of the limitations of the cooling effect of permeable paving is that when there is no rainfall to evaporate, they do not cool their environment. Traditionally, the focus on stormwater management has been to quickly discharge the peak flow into stormwater drains or encourage infiltration. However, by harvesting rainwater, storing it, and allowing it to evaporate from surfaces, not only helps to level out the peak flow of storm events, but it also extends the time permeable paving has a cooling effect.

RBC Rain Garden at the London Wetland Centre by Marathon CC2.0

-

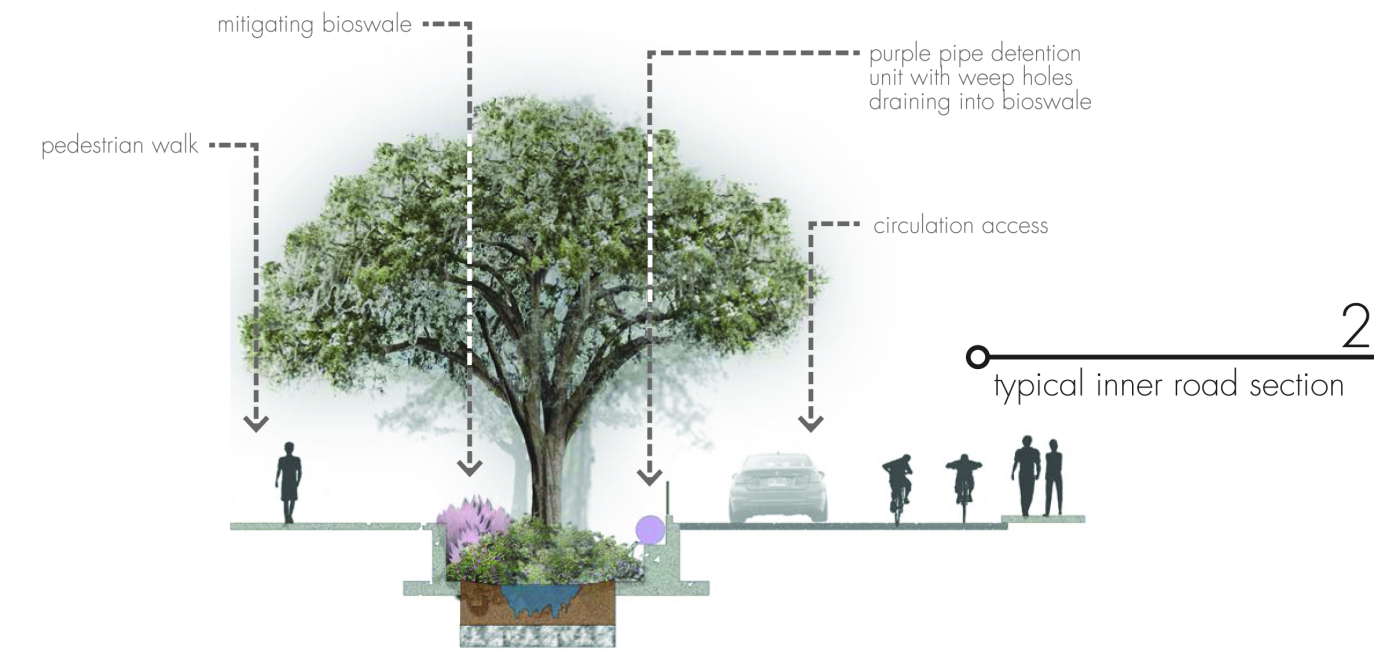

Rain gardens and swales

Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) have proven benefits for stormwater attenuation. Rain gardens and swales are forms of SUDS that collect rainwater during storm events and allow it to slowly infiltrate into the ground. As they retain the water for a period, the water has a greater time to evaporate. By including planting, rain gardens also perform evapotranspiration, cooling the air further.

Landscape Architecture Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect.

There are several ways architects and landscape architects can reduce the urban heat island effect. Through technological means, the albedo of surfaces can be increased to reflect more of the sun’s energy, thus reducing the amount of energy absorbed by buildings.

However, there are also a great many tools at the landscape architect’s disposal that can mitigate the UHI effect. By incorporating green roofs and green walls some of the sun’s energy can be reflected, rather than absorbed. By including shade producing deciduous street trees into the streetscape, sidewalks and buildings can be shaded from the sun. Permeable paving can encourage evaporative cooling at the street level, and when used in conjunction with rainwater harvesting can provide maximum cooling when it is needed most. Finally, many sustainable urban drainage system tools can be used to retain water in the landscape, providing evaporative cooling. All these measures will help reduce the ambient temperature of the local microclimate and mitigate the overall urban heat island effect.

LEAD IMAGE: Urban heat island effect by Alexandre Affonso

Banyoles Old Town Redesign Highlights the Medieval Footprint of the City

The design of open-air public spaces in cities with historical backgrounds usually borrows inspiration from the past. Periods such as the Αncient Τimes, the Renaissance, and the Μiddle Αges left strong footprints in major capitals of Europe, but these periods also left their marks in smaller towns.

Banyoles is one such small town in Catalonia where visitors feel like they are traveling back in time. So, it comes as no surprise that Miàs Arquitectes decided to bring back the town’s medieval character to the newly renovated town center. Their decision was based on the center’s location, surrounded by old buildings and architectural features with a strong past.

Miàs Arquitectes’ design references the medieval past of the city, while also striking a balance between the functional and aesthetic features. The Banyoles redesign project became one of the most successful projects the team has designed and it received several awards and recognition including the Catalonia Construction Award (2009) and Girona Area Architectural Awards (2007).

The Historical Footprint

In the 9th century, the monks of Sant Esteve Monastery excavated the land around Banyoles to create a drainage canal system, which also linked the city to Lake Banyoles. The purpose of the drainage channels was to supply the city with water from the lake and to offer flood protection for the city. The water was also used in agribusiness and pre-industrial craft works. The footprint of the canal was well maintained and can still be seen in the layout and architecture of the remaining buildings. Many of these buildings are made of travertine stone, found locally in the subsoil of the town.

The Modern Situation Downplayed the History

In modern years, the drainage channels were covered and eventually joined with the city’s sewer system. Losing its key feature, Banyoles became a deteriorated zone without charm. The urban framework of narrow sidewalks in the town center was essentially a point of cohabitation between pedestrians and vehicles with covered channels and pedestrian areas around the Central Square used as periodic parking spaces. This situation led the town authorities to search for an architectural solution that would bring the attraction back and form a significant center, combined with a more contemporary aspect.

Sculpting the Layers of the City

The Banyoles City Council commissioned Miàs Architects to redesign the center of Banyoles. As a city with a long past, the first decision was to choose which previous era should be brought back to the surface. The medieval town of Banyoles provided the most architecture, so designers decided it would be the best time period to restore. The design stated that almost all of the accessible areas should be pedestrianized, removing the old sidewalks. The removal of the old sidewalks allowed the historical layers of the town to emerge, including the remains of buildings, old canals, and tombs.

An Ode to Travertine Stone

The calcareous stone, travertine, resides in the subsoil of Banyoles and was often used in the architecture of Banyoles. With this in mind, the architects designed a pedestrian network that unites the squares of the city. The plan was based on an arrangement of successive squares, among them the ‘Plaça dels Turers’, ‘Plaça Major’ (Central Square), ‘Plaça dels estudis’ (Studies Square), ‘Plaça de la Font’ (Water Source Square), ‘Plaça del teatre’ (Theater Square), ‘Plaça de l’església Santa Maria’ (Square of the Church of Santa Maria), and the ‘Plaça del monestir’ (Monastery Square). The squares were named for the important buildings located within them, mainly museums or churches.

The architectural idea of Miàs Arquitectes ‘covers’ the city center in a travertine stone mosaic with the Central Square as its departing point and extending out to the open spaces of smaller squares. As a complete project, it looks like the ground has lifted to form the medieval houses, mysterious buildings, monuments, and churches, even though they have always been there.

Floating Over the Past

The flow of water was a key element of the city’s everyday life. The second strong movement of the project was to bring water back into the city through the irrigation canals. The existing canals that had been covered for years were exposed and new ones were created as sections to the stone ground. In some canals, the ground increases infinitely, attracting children to play, while other canals allow water to flow around the center, giving inhabitants the sense of serenity while wandering in the ‘new’ city.

The urban furniture used in the design is quite minimal, highlighting the two main features, water and stone. Wooden seats have been placed in groups, in the open spaces, creating small ‘neighborhoods’ with deciduous trees placed around them in a linear fashion. The change in the foliage of the trees creates alternating scenery through the seasons.

As the city is a fusion of historical layering, the Banyoles redesign project uses the past as a material for a contemporary public space. The logic of the architectural idea avoided the usual practice of adding one more layer to the city, and instead, turned to the daylighting of an older layer.

In the words of the architect, Josep Miàs Gifre, “We chose the same material in which all the city center is built. We break the linearity of the pedestrian paths, making cuts in their surface so the flow of water can be felt. We strongly believe that the old town will now become a sequence of paths in which the inhabitants would have the possibility to enjoy the historical center and its 12th century architecture.”

Project Information

Architect: Josep Miàs (Miàs Architects)

Project team: Silvia Brandi, Adriana Porta, Mario Blanco, Josep Puigdemont, Fausto Raposo, Mafalda Batista, Judith Segura, Sophie Lambert, Sven Holzgreve, Thomas Westerholm, Oliver Bals, Marta Cases, Julie Nicaise, Lluís A. Casanovas, Anna Mallén, Bárbara Fachada, Marco Miglioli

Completion date: 2011

Location: Banyoles – Girona – Spain

Client: Public – Banyoles City Council

Size: 18.000 m2

Budget: 4M €

Technical Architect: Albert Ribera

Engineer: Josep Masachs

Photographer: Adrià Goula

Awards: 2007, PREMIS D’ARQUITECTURA COMARQUES DE GIRONA Winner

2008, EUROPEAN PRIZE FOR URBAN PUBLIC SPACE Finalist

2008, 5th ROSA BARBA EUROPEAN LANDSCAPE PRIZE Finalist

2008, PREMIO ESPACIO PÚBLICO EUROPEO CCCB Finalist

2009, PREMI CATALUNYA CONSTRUCCIÓ Winner

2010, PREMIS FAD Finalist

All images courtesy of Adrià Goula.

10 Reasons Why Cities Should Daylight Rivers

We explore the reasons why cities should daylight rivers. Every city in the world has hidden secrets which lie beneath its tarmac, concrete or buildings. In many cities, these secrets come in one powerful form: underground rivers and streams. Some cities have recognised the potential to lift the lid off these watercourses and “Daylight” them. The results have been astonishing and have benefitted the natural, urban as well as the social environments. With this in mind, we thought we would highlight 10 reasons why more cities should do the same.

Daylight Rivers

1. Reduce Flooding Many streams and rivers in cities have been forced to go underground in an attempt to remove stormwater as quickly as possible from the urban environment. This, however, often results in a flash flood during heavy rains as the underground systems become overloaded. By daylighting, the course of water can be retained, slowed down, and diverted, while at the same time reducing the risk of blockages at choke points.

Thornton Creek, Seattle where a large paved parking lot with an underground pipe was restored to an open channel with four chambers that accommodate flood and filters sediment. Image courtesy of Peggy Gaynor, GAYNOR, Inc.

3. Boost Ecology By depriving the water of sunlight, buried watercourses become ecological deserts, devoid of any natural life. Exposing rivers or streams to daylight allows for the re-establishment of plant and animal life. See More River Related Articles:

- Extraordinary Development Re-connects City With The River Bank

- The Amazing Zhangjiagang Town River Reconstruction

- Turenscape Design Outstanding River Park

The Saw Mill River in Yonkers, New York, saw the transformation of a buried river into a natural river bed. This new green urban park is now home to 8 species of fish and numerous birds. Image courtesy of Donna Davis/Ms. Davis Photography.

5. Create Green Corridors Daylighting rivers has the potential to unlock natural beauty in the heart of the city. Areas which were once hardened and lifeless can be transformed by unveiling the water beneath and re-introducing vegetation to create a green urban corridor. 6. Reduce Urban Heat Island Effect The Urban Heat Island Effect is the condition where extreme temperatures occur in the city due to radiation from hardened surfaces. Daylighting rivers and streams in cities has the ability to dramatically moderate temperatures. Cheonggyecheon River, Seoul by SeoAhn Total Landscape transformed a six-lane highway into a green urban waterway. This transformation has not only created an active urban park but has reduced temperatures along the stream by up to 6 degree Celsius.

“Korea-Seoul-Cheonggyecheon-2008-01” by stari4ek – originally posted to Flickr as fest2-01. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons

In 2013 SCAPE landscape architects won a competition to design a master plan to daylight the Town Branch Creek in Lexington. Their proposal was called “Reveal, Clean, Carve, Connect” and sought to create site-specific interactions which would transform the inner city. Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE.

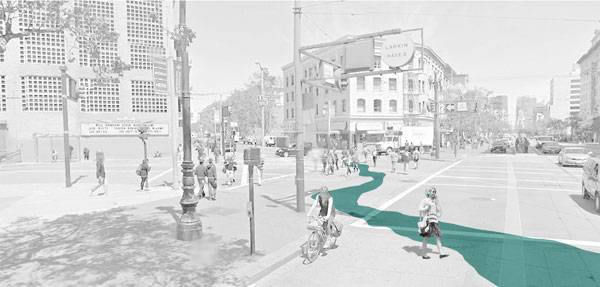

In San Francisco a project called Ghost Arroyos has begun to draw on the history of the hidden streams. While the streams haven’t yet been daylighted, their presence has been highlighted through an art installation where the watercourse has been painted onto the urban surfaces. Image courtesy of Emily Schlickman and Kristina Loring.

Recommended Reading:

- Drawing and Designing with Confidence: A Step-by-Step Guide by Mike W. Lin

- Landscape Perspective Drawing by Nicholas T. Dines

Article by Rose Buchanan Return to Homepage

EPA Announces Winners of the 2013 Campus RainWorks Challenge

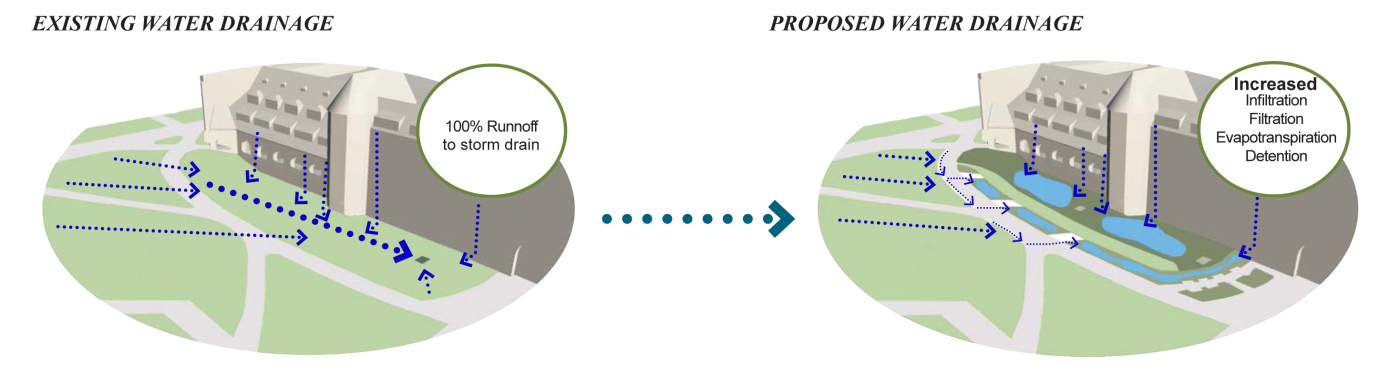

Standard urban development builds systems designed to move stormwater quickly away from where it falls. The efficiency of gutter and pipe systems allows stormwater to carry sediment, bacteria, nutrients, and even heavy metals into bodies of water. It also places more stress on natural waterways because runoff is quickly discharged into main systems, increasing peak flows. To encourage non-traditional thinking about drainage systems, the EPA has asked students to examine how green infrastructure can reduce these issues.

A seating nook designed beside a rain garden and wet meadow in a winning entry from Kansas State.

The EPA’s annual Campus RainWorks Challenge prompts university students to propose utilizing green infrastructure on their campuses. The competition aims to have students consider and promote both the functional and economic potential that green infrastructure can provide. It also strongly encourages interdisciplinary collaboration, being open to fields including landscape architecture, planning, engineering, biology, hydrology, and even economics. Each entry is judged on its effective performance, its innovation and value to campus, the level of interdisciplinary collaboration, and level of proper documentation. This April, the EPA announced winners from 84 team entries in two categories, Master Plan and Site Design.

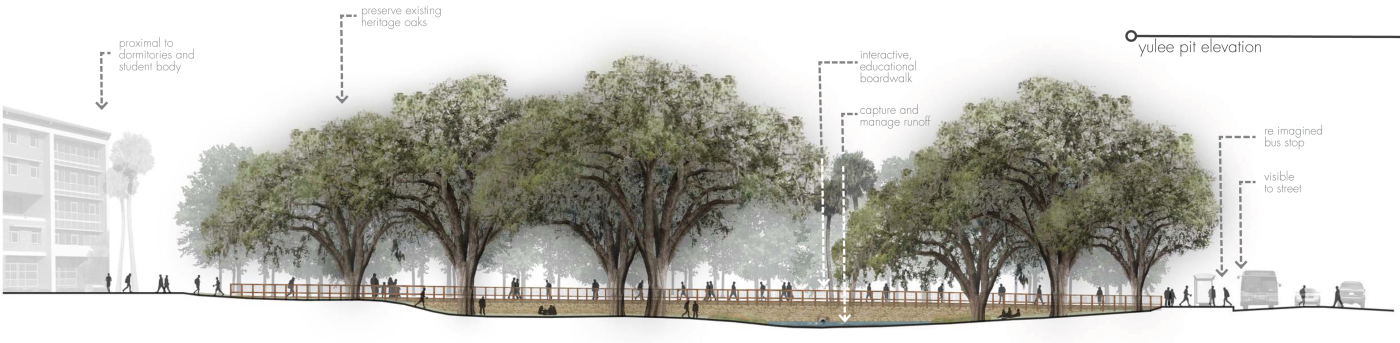

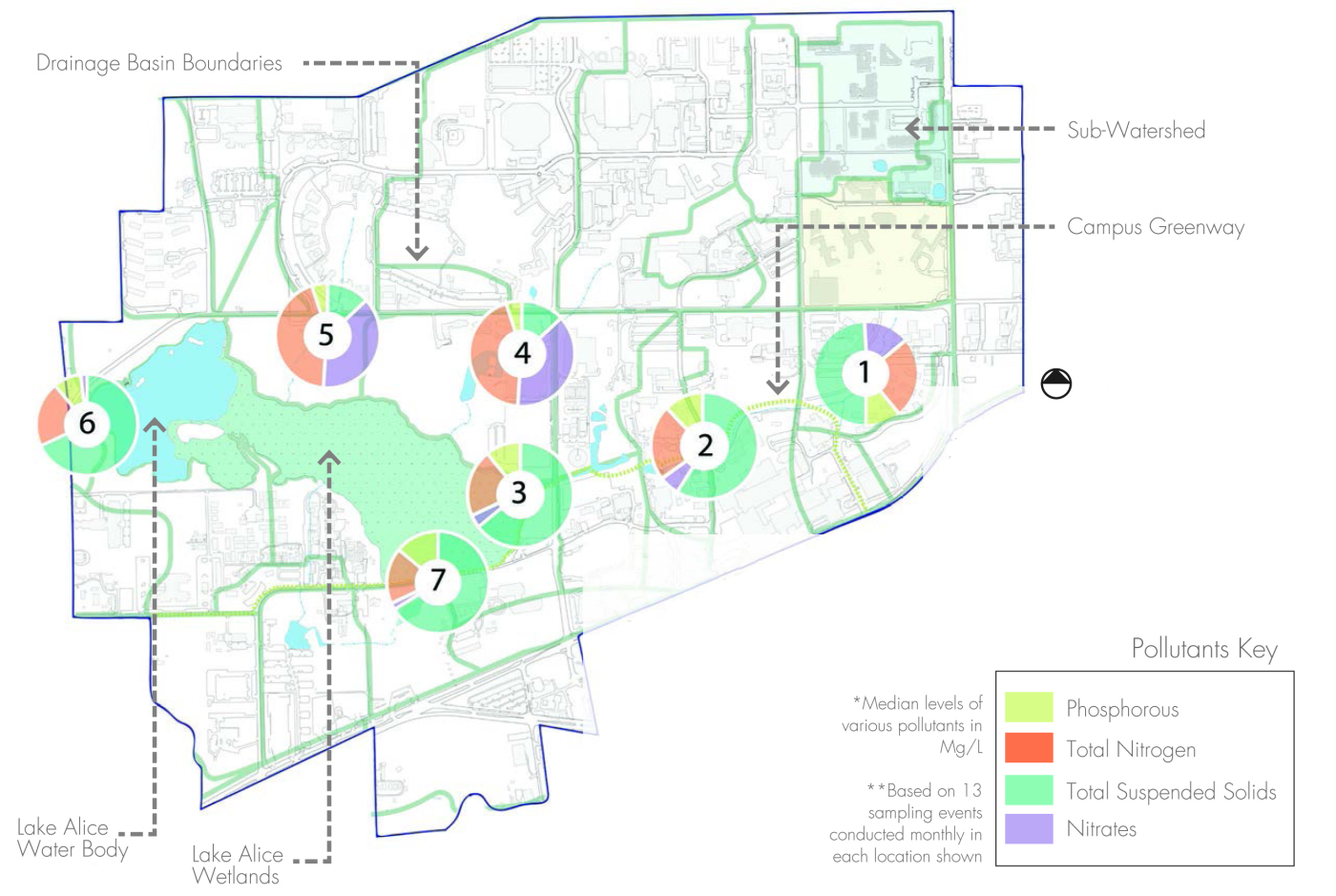

Master Plan Category | First Place: University of Florida

The University of Florida nabbed first place in the Master Plan category. The team developed a proposal which treats the stormwater produced in a 67.6 acre watershed on campus for rainfall events up to a 100 year storm. At the University of Florida, stormwater is handled through a complex network of pipes which convey the water to the south end of campus, released into natural water bodies, and ends up in Lake Alice, the original detention pond for built for campus.

Related Story: Philly Grad Creates Free Cloud-Based Stormwater Modeling Tool

The team proposed daylighting the underground stormwater infrastructure in an “artful treatment matrix”. In place of rapid conveyance systems, the team used surface-based green infrastructure to treat and slow the stormwater as preemptive pollution and flood mitigation as it moves from north to south on campus towards Lake Alice. The three-phased plan included a large bioretention pond to replace the current holding pit. Other measures include two more detention areas – one pond and a linear basin along a main thoroughfare – as well as rain gardens interspersed with playful water elements like a purple weeping pipe.

University of Florida: The map shows the focus watershed and downstream areas with significant pollution.

The plan of the Master Plan’s upper zone releases water from current infrastructure into the proposed above-ground system. The final stage of the campus stormwater detention system is shown in the lead image.

A purple pipe, which later discharges into green infrastructure, calls attention to the path of stormwater throughout campus.

Bioswales separate vehicular and pedestrian circulation. They add both functional and aesthetic value to the street.

The Yulee Pit is the final point in the proposed campus water retention and mitigation system.

Site Design Category | First Place: Kansas State University

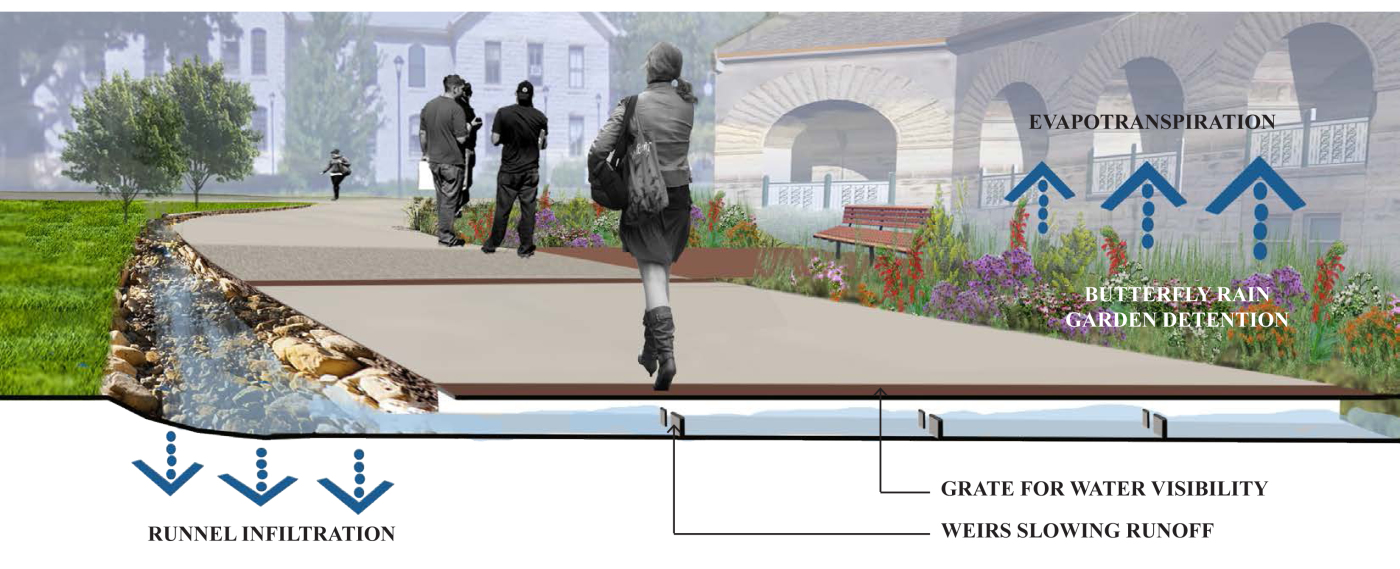

In the Site Design category, Kansas State placed first. The team responded to a $5.1 million recommendation from a consulting engineer firm to fix campus stormwater issues by enlarging the existing pipe network. The team wanted to demonstrate that the issues could be addressed through green infrastructure methods by slowing and reducing the stormwater entering the system. They focused their proposal on a strip of lawn bordering the commons next to the campus library.

Related Story: 5 Resiliency Lessons from NYC Stormwater Projects

As a highly visible part of campus, the design provides both technical performance and education. Two small, existing depressions were reworked to create a wet meadow. Combined with several small rain gardens, the site retains all the stormwater from a one year storm and 65% from a ten year storm. The team also utilized a striking combination of details to bring attention to the functional stormwater management features. Where the site borders the commons, stone runnels collect water, which is then conveyed under decorative grates across the path into the bio-retention areas. The vegetation scheme reflects a native Kansas prairie ecosystem, transitioning from wet to mesic to dry plant communities as the terrain moves above the retention zone. The native vegetation, in addition to its stormwater benefits, replaced low-functioning irrigated lawn.

Kansas State: The proposed site creates a new, more lively front for the university library facade.

While the existing site condition sends all runoff off site in pipes, the proposed design retains all the runoff produced in its watershed from a one year storm event.

Stormwater runoff is collected from the lawn and conveyed across the path to bioretention areas.

The plant palette developed by the Kansas State team reflects a sensitivity to native plant communities and topography.

To see the winning entries, as well as second place and honorable mentions, go to the EPA’s Campus RainWorks Challenge page. The 2014 call for entries has already begun. Registration closes October 3, and entries are due December 19.

All images provided by the EPA.

What Makes a Biophilic City?

Joseph Clancy, emerging expert on biophilia looks at what makes a biophilic city. To what degree must a city engage in biophilia to be classed as a “biophilic city”? Timothy Beatley describes a biophilic city as being “partly defined by the qualities and biodiversity present and designed into urban life, but also the many activities and lifestyle choices and patterns, the many opportunities residents have to learn about and be engaged directly in nature, and the local institutions and commitments expressed, for instance, in local government budgets and policies”. So how do we classify a city as a biophilic city?

According to the works of Timothy Beatley, Biophilic Cities can be indicated by the following qualities:- Biophilic cities have abundant nature in close proximity to large numbers of urbanites

Green infrastructure programs, parklets & a high percentage land cover of green space would be steps towards fulfilling this aspect of a biophilic city. New York City qualifies as a biophilic city in this regard by PlaNYC’s goal of a public green space within a 10 minute walk of every resident by 2030, while Seattle P-Patch program aims for one community garden per 2,500 city inhabitants!

The Highline is a great example of a planting scheme increasing biodiversity in an urban area; credit: shutterstock.com

- In biophilic cities, residents feel a deep affinity with the unique flora, fauna and fungi found there

Incentive, education and encouragement from city authorities are necessary to catalyze this goal. It measures not just the environmental values of inhabitants, but their knowledge of local and native species. In New Zealand, the city of Wellington also has over sixty community conservation groups! In the last two years alone, volunteer environmental groups have performed 28,000 hours of service on Wellington’s 4,000 hectares of nature reserves. While in Oslo, Norway, over 81% of inhabitants had visited the city’s surrounding forests in the last year, proving residents appreciation of the natural landscape.

- Biophilic cities are cities that provide abundant opportunities to be outside and to enjoy nature

Urbanization causes severe fragmentation of habitats and nature, with land value at a premium, resulting in little room for green space. Well connected green spaces and green corridors can counter this problem, easing accessibility for urban inhabitants. Singapore has an extensive park system, integrated by 200-kilometers of Park Connectors, in the form of elevated walkways. Oslo, Norway is perhaps the leader in this category however, with an estimated 94% of the city’s residents living within 300 meters of a park! Anchorage, Alaska has 1 mile (1.6Km) of natural walking trails per 1,000 residents. The trails are multi use and seasonal, offering everything from hiking to skiing.

- Biophilic cities are rich multisensory environments, where the sounds of nature are as appreciated as much as the visual or ocular experience

The integration of natural spaces and ecological corridors into the urban fabric can create the conditions necessary for multisensory, nature rich environments. Implementing a Noise Reduction Plan or reducing levels of vehicular transport, would create “quiet zones”, with noise levels below 50 decibels (dB). Oslo, Norway is attempting an initiative of daylighting all eight of the city’s rivers. This will form part of the Akersleva, a combined green and blue infrastructure corridor, connecting the city centre inhabitants with nature in the very heart of the city, with 14 quiet zones planned within the corridor.

Akerselva goes into tunnel at Vaterlandsparken, Vaterland / Grønland, Oslo. Credit: Helge Høifødt, CC 3.0

- Biophilic cities invest in the social and physical infrastructure that helps to bring urbanites in closer connection and understanding of nature

Investment in biophilic projects is an excellent indicator of a biophilic city. Timothy Beatley identifies 5% of a cities budget dedicated to biodiversity and at least 1 current biophilic project in operation as indicative of governance in a biophilic city. Portland, Oregon, exceeds this and has invested heavily in social & green infrastructure, with Portland having the highest parks per-capita acreage in America. While Singapore’s N’Parks have an incentive program, entitled Skyrise Greenery, for green roofs & living walls, offering up to 75% of the cost.

- Biophilic cities place importance on education about nature and biodiversity, and on providing many and varied opportunities to learn about and directly experience nature

Education can result in reinforcing positive feelings about nature and encouraging sustainable living among the general population. In Limerick City, Ireland, several environmental groups are working with the support of the city council to educate the city’s population on biodiversity and native wildlife species. Urban Tree Project and Limerick City Biodiversity Network have engaged the local population with nature, while providing guided walks, lectures and online resources to educate the city’s inhabitants on the importance of biodiversity.

- Biophilic cities take steps to actively support the conservation of global nature

With cities being the epicentre of governance, innovation, employment and population, they have a necessary role in the conservation of nature on a regional, national and international scale, given their ecological footprint and negative impacts upon the environment. Such measures include; set aside of land, designation for protected sites, the creation of a biodiversity action plan and focus on compact development. In the city of Nagoya, Japan, 10% of urban land cover is set aside to be left in an unmanaged wild state as nature preserves. Below: The Nature of Cities TRAILER While Phoenix, Arizona has taken this a step further by purchasing over 17,000 acres of natural desert for nature conservation, to help mitigate the negative effects of Phoenix’s urban sprawl. Then there is Vitoria-Gasteiz, in Basque country, encircled by a green belt to restrict encroaching development and to protect the internationally important restored wetland, the Salburua. However, the city still intends to create the Anilla Verde Interior—“the interior green belt”! These indicators focus on the protection, enhancement and introduction of nature into our cities, while encouraging interaction with nature by the city’s inhabitants through the process of environmental education and habitat restoration. With more than half of the world’s population living in urban centres devoid of nature, biophilic cities are no longer a choice. The benefits & criteria have been discussed, in my next article I will countdown the Top Ten Biophilic Cities. Recommended reading: Biophilia by Edward O. Wilson Design with Nature by Ian L. McHarg Article written by Joseph Clancy Featured image: MEC’s green roof. Credit: sookie – Flickr CC BY 2.0

This article was originally submitted to Landscape Architects Network

5 Resiliency Lessons from NYC Stormwater Projects

| Exactly eight months ago, HUD Secretary and Chair of the Sandy Rebuilding Task Force Shaun Donovan announced the Rebuild by Design competition, an “innovation and resilient design in Sandy rebuilding” collaborative with the Rockefeller Foundation and the NYU Institute for Public Knowledge. Secretary Donovan remarked that the catalyst for the competition was the recognition that the federal government “cannot fill every need.” Ideas and additional funding are expected of other institutions and that universities, community leaders, nonprofit organizations, and citizens are essential to creating solutions that work across scales and interconnected systems. |

Image credit: rebuildbydesign.org

The clock for the competition started on June 20 with the request for qualifications due July 19. The competition, which has multiple phases, will announce its finalists next month. Selected ideas will be implemented with Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery money and funding from other public as well as private partners. Each team must have multi-disciplinary expertise and have active collaborations with local and regional institutions. The competition organizers and jury are seeking buildable solutions in four categories: small to mid-size coastal communities; high density urban environments; ecological and waterbody networks; and “outside the box” proposals.

Rebuild by Design was announced eight months after Superstorm Sandy made landfall in the region. However, immediately after, and in some cases well before the storm, various actors in New York City implemented and proposed best management practices for stormwater management. Stormwater here is broadly defined as upland or coastal flooding from ocean surge and surface runoff. Government, community-based organizations, nonprofits, and citizens have engaged in activities to reduce individual, community, and city-wide exposure and vulnerability to flooding and surge events. Risk reduction activities range from new and continuing landscape construction projects to recovery policies and plans by federal, state and municipal actors to design proposals by landscape architects and other allied professionals. Innovation is a hallmark of design competitions but in addition to reinventing the wheel thinking, it is worthwhile to glean not only design, but cultural, lessons from ongoing green-blue infrastructure efforts.

Image credit: rebuildbydesign.org

In the rest of this essay, lessons from five storm-water management projects will be presented. The cases are the dune restoration in Long Beach, NY; the Sunset Park segment of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway; wet meadow restoration and rainwater catchment in Brook Park in the Bronx; the Nashville Boulevard and 116th Avenue Greenstreet in Queens; and SCAPE’s Oyster-tecture proposal for the 2010 MoMA Rising Currents exhibition. These lessons should be useful to those engaged in the Rebuild by Design competition, as well as others engaged in stormwater management efforts.

Dune restoration in Long Beach, NY

One direct landscape intervention is the dune restoration in Long Beach, NY. In this community, approximately half a million cubic yards of sand were washed away during the storm. The diminished sand dunes make the community vulnerable to even the mildest of storm events.

Dune grasses require “a significant accumulation of sand” so residents proposed to city officials that discarded Christmas trees be placed on the beach to capture blowing sand. The New York Times also reported that other Sandy-affected communities as well as storm-prone communities elsewhere (Carolinas, Louisiana, and California) have repaired dunes with this method.

The dune restoration project in Long Beach offers two lessons. First, in the aftermath of disasters, citizens are often the “first responders” according to Erika Svendsen, a social science researcher with the U.S. Forest Service. Secondly, Keith G. Tidball and colleagues argue that the restoration response is not simply one of reducing exposure and physical vulnerability, but also of developing “social-ecological resilience”, i.e. post-disaster greening activities that beget community engagement and ecological learning.

Rebuild by Design teams should develop systems that (continue to) enable communities to respond effectively to disasters. Furthermore, proposals could be designed as living documents to easily accommodate ongoing learning as well as changes in a community’s demographics and geological form.

|

| Image: Belltown P-Patch, Seattle |

Sunset Park segment of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway

Cultural perceptions of nature are another key lesson from ongoing water hazard reduction activities. According to the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative (BGI), a planning and long-term stewardship non-profit, the 14-mile, 23-segment Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway will incorporate green infrastructure strategies along much of its length.

Although BGI is the lead nonprofit for the greenway, a conceptual plan for the Sunset Park segment was commissioned by United Puerto Rican Organization of Sunset Park (UPROSE), a community-based environment, sustainable development and youth justice organization. Since culturally-appropriate design is identified as one of seven planning principles in the Conceptual Plan for a Sunset Park Greenway, “local stakeholders should be involved in the aesthetic design process for physical greenway elements so that the final product communicates a sense of identity and ownership.”

Although nature values are not specifically mentioned, given the nature of the UPROSE’s campaigns, it is likely that cultural ideas about what constitutes ecological design are embedded in its conceptual plan for the greenway. This call for culturally appropriate design mirrors Julian Agyeman’s concept of “culturally inclusive spaces” in which cultural aesthetic and use values of nature are honored while simultaneously stewarding ecological health and function.

The “look” of green infrastructure components for the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway might be different than the traditionally linear bioswale as shown in typical design schematics. Anja Claus of the Center for Humans & Nature suggests that a swale could be “a string of landscape depressions of varying shapes representing some cultural story.” Furthermore, the swale could be vegetated with plant species that provide both cultural meaning and ecological function.

|

| Image: Future site of wet meadow, Brook Park, Bronx |

Wet meadow restoration and rainwater catchment in the Bronx

The Friends of Brook Park has undertaken a restoration plan for a wet meadow and rain water catchment system along a section of the historic Mill Brook. The planning for the restoration project began long before Hurricane Sandy but claims about the project’s ability to reduce upland flooding and reduce contributions to downstream CSOs align it not only with the city’s pre-storm sustainability and green infrastructure plans but also with the post-storm rebuilding and resiliency plan.

The Brook Park project exemplifies the creative grassroots and capacity building of the Friends. When former Mayor Giuliani proposed to sell the city’s community gardens, South Bronx community groups coalesced around open space preservation. The park was created when its founders cut the fence around a local vacant lot and started an after-school program for with funding from the Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation.

The restoration plan was initiated when a neighbor showed the Friends group maps of the historic creek in 2005. The park received a grant from the U.S. Forest Service Living Memorials Project to plant trees. Currently, the restoration project is in the design and implementation phase.

Although navigating the city’s green infrastructure bureaucracy has been challenging, this step-wise process has meant that the park’s stewards have been, borrowing from Marcia McNally, caring for and feeding their own grassroots. Grassroots does not imply lack of sophistication. The design for the stormwater capture wetland system is elegant. (Although the original Brook Creek flows under the site, it will not be daylighted in the traditional sense. An impermeable layer will separate the constructed wetland and the original creek flow.)

The wetland in conceived of as three separate ponds that will be fed by precipitation that falls on the site. The other source of water for the ponds will be rainwater harvested from the roofs of 28 adjacent townhouses. Runoff from a different set of five townhouses will be used for gravity-fed irrigation. The estimated combined total rainfall from townhouse roofs and the park is 39,281 gallons during a 1” rain event and 1,571,250 gallons annually.

|

| Image: Furmanville Avenue Greenstreet, Queens |

Nashville Boulevard and 116th Avenue Greenstreet in Queens

At the Waterproofing New York symposium in March 2013, Jeannette Compton, director of the Green Infrastructure Unit of the Department of Parks and Recreation, described some of the city’s Greenstreets as “hyperfunctioning,” meaning that they perform beyond their footprint. The city’s Greenstreets program was initiated in 1996 with the Department of Transportation; the original objectives of the program were to “beautify neighborhoods, improve air quality, reduce air temperatures, and calm traffic” by vegetating impervious, unused road areas.

In 2010, the program evolved into the Green Infrastructure Unit and partnered with the Department of Environmental Protection to manage runoff and meet sewershed and water quality goals. The new Greenstreets are overdesigned to “absorb runoff from an area 10 or more times their size”.

This was illustrated at the Nashville Boulevard and 116th Avenue Greenstreet in Queens during Superstorm Sandy. Compton reported that the greenstreet received 1,200-1,300 gallons of direct rainfall and 39,000 gallons of runoff flowed into the system (surrounding storm drains were clogged with storm-generated debris).An approximate total of 40,000 gallons of water was handled by the greenstreet over the course of two to three days. Most of the water was held in the top layers soil and there was no water in the catchment basin which means the system had capacity to handle more water. The new portfolio of Greenstreets can handle routine 1” rain events as well as hurricane-level precipitation.

Image via Wikimedia

Oyster-tecture by SCAPE

Also, it is okay to be radical. Kate Orff, who heads the landscape architecture firm SCAPE, submitted Oyster-tecture, “a living reef” of oysters, mussels and eelgrass, to the MoMA Rising Currents exhibition in 2010 (one year before Hurricane Irene and two years before Superstorm Sandy). At the time, the concept of oyster-tecture was fairly radical. Although oysters were known to attenuate wave action, designing green infrastructure with oysters was not a mainstream strategy in New York in 2010, though the times have changed. Oyster reefs have even been listed as a strategy for coastal protection in the NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency report released in June 2013.

Five lessons

There are five lessons from the case studies outlined above.

- One, plans to reduce risk in coastal and upland areas should acknowledge the critical first responder role played by residents.

- Two, design solutions should function in typical and beyond anticipated storm scenarios. However, these hyper-functioning solutions should not be supersized; they should match the scale of the neighborhood.

- Three, competition participants should take inspiration from Oyster-tecture and follow their outside-the-box concepts.

- Four, community members should also pursue their creative solutions; wetlands in the Bronx are not uncanny.

- And five, don’t ignore local strategies and community planning in the push for regional solutions and master planning; the sustainability of Rebuild by Design proposals will require that local visions of nature are meaningfully incorporated into projects.

Lead Image: Current Rebuild by Design proposals via Rebuild by Design (source)

Follow Rebuild by Design at http://www.rebuildbydesign.org.

Additional photographs of Brook Park are available at Nature Park – Brook Park.

Originally published on Thursday, February 6, 2014 as “5 Lessons for Rebuild by Design from existing NYC stormwater projects” on local ecologist.

Think you can write?

So you’ve read through what we’ve got, maybe you think you could do just as good or maybe you think you could do better, here at Landscape Architects Network we’re always searching for new talent but more importantly we’re searching for individuals who have ambition and want to be part of something great. So don’t just sit there, don’t just be a critic, get typing, contact us and apply to become part of our growing writing team, make a difference, be the voice, get involved and get active. We’re waiting for you! The LA Team Check out this sample article below: Joseph Clancy, emerging expert on biophilia looks at what makes a biophilic city. To what degree must a city engage in biophilia to be classed as a “biophilic city”? Timothy Beatley describes a biophilic city as being “partly defined by the qualities and biodiversity present and designed into urban life, but also the many activities and lifestyle choices and patterns, the many opportunities residents have to learn about and be engaged directly in nature, and the local institutions and commitments expressed, for instance, in local government budgets and policies”. So how do we classify a city as a biophilic city?

According to the works of Timothy Beatley, Biophilic Cities can be indicated by the following qualities:- Biophilic cities have abundant nature in close proximity to large numbers of urbanites

Green infrastructure programs, parklets & a high percentage land cover of green space would be steps towards fulfilling this aspect of a biophilic city. New York City qualifies as a biophilic city in this regard by PlaNYC’s goal of a public green space within a 10 minute walk of every resident by 2030, while Seattle P-Patch program aims for one community garden per 2,500 city inhabitants!

The Highline is a great example of a planting scheme increasing biodiversity in an urban area; credit: shutterstock.com

- In biophilic cities, residents feel a deep affinity with the unique flora, fauna and fungi found there

Incentive, education and encouragement from city authorities are necessary to catalyze this goal. It measures not just the environmental values of inhabitants, but their knowledge of local and native species. In New Zealand, the city of Wellington also has over sixty community conservation groups! In the last two years alone, volunteer environmental groups have performed 28,000 hours of service on Wellington’s 4,000 hectares of nature reserves. While in Oslo, Norway, over 81% of inhabitants had visited the city’s surrounding forests in the last year, proving residents appreciation of the natural landscape.

- Biophilic cities are cities that provide abundant opportunities to be outside and to enjoy nature

Urbanization causes severe fragmentation of habitats and nature, with land value at a premium, resulting in little room for green space. Well connected green spaces and green corridors can counter this problem, easing accessibility for urban inhabitants. Singapore has an extensive park system, integrated by 200-kilometers of Park Connectors, in the form of elevated walkways. Oslo, Norway is perhaps the leader in this category however, with an estimated 94% of the city’s residents living within 300 meters of a park! Anchorage, Alaska has 1 mile (1.6Km) of natural walking trails per 1,000 residents. The trails are multi use and seasonal, offering everything from hiking to skiing.

- Biophilic cities are rich multisensory environments, where the sounds of nature are as appreciated as much as the visual or ocular experience

The integration of natural spaces and ecological corridors into the urban fabric can create the conditions necessary for multisensory, nature rich environments. Implementing a Noise Reduction Plan or reducing levels of vehicular transport, would create “quiet zones”, with noise levels below 50 decibels (dB). Oslo, Norway is attempting an initiative of daylighting all eight of the city’s rivers. This will form part of the Akersleva, a combined green and blue infrastructure corridor, connecting the city centre inhabitants with nature in the very heart of the city, with 14 quiet zones planned within the corridor.

Akerselva goes into tunnel at Vaterlandsparken, Vaterland / Grønland, Oslo. Credit: Helge Høifødt, CC 3.0

- Biophilic cities invest in the social and physical infrastructure that helps to bring urbanites in closer connection and understanding of nature

Investment in biophilic projects is an excellent indicator of a biophilic city. Timothy Beatley identifies 5% of a cities budget dedicated to biodiversity and at least 1 current biophilic project in operation as indicative of governance in a biophilic city. Portland, Oregon, exceeds this and has invested heavily in social & green infrastructure, with Portland having the highest parks per-capita acreage in America. While Singapore’s N’Parks have an incentive program, entitled Skyrise Greenery, for green roofs & living walls, offering up to 75% of the cost.

- Biophilic cities place importance on education about nature and biodiversity, and on providing many and varied opportunities to learn about and directly experience nature

Education can result in reinforcing positive feelings about nature and encouraging sustainable living among the general population. In Limerick City, Ireland, several environmental groups are working with the support of the city council to educate the city’s population on biodiversity and native wildlife species. Urban Tree Project and Limerick City Biodiversity Network have engaged the local population with nature, while providing guided walks, lectures and online resources to educate the city’s inhabitants on the importance of biodiversity.

- Biophilic cities take steps to actively support the conservation of global nature

With cities being the epicentre of governance, innovation, employment and population, they have a necessary role in the conservation of nature on a regional, national and international scale, given their ecological footprint and negative impacts upon the environment. Such measures include; set aside of land, designation for protected sites, the creation of a biodiversity action plan and focus on compact development. In the city of Nagoya, Japan, 10% of urban land cover is set aside to be left in an unmanaged wild state as nature preserves. Below: The Nature of Cities TRAILER While Phoenix, Arizona has taken this a step further by purchasing over 17,000 acres of natural desert for nature conservation, to help mitigate the negative effects of Phoenix’s urban sprawl. Then there is Vitoria-Gasteiz, in Basque country, encircled by a green belt to restrict encroaching development and to protect the internationally important restored wetland, the Salburua. However, the city still intends to create the Anilla Verde Interior—“the interior green belt”! These indicators focus on the protection, enhancement and introduction of nature into our cities, while encouraging interaction with nature by the city’s inhabitants through the process of environmental education and habitat restoration. With more than half of the world’s population living in urban centres devoid of nature, biophilic cities are no longer a choice. The benefits & criteria have been discussed, in my next article I will countdown the Top Ten Biophilic Cities. Recommended reading: Biophilia by Edward O. Wilson Design with Nature by Ian L. McHarg Article written by Joseph Clancy

This article was originally submitted to Landscape Architects Network