Author: Brian Barth

4 Best Places for Urban Agriculture in the United States

Our Land8 Urban Agriculture series is finally coming to a close, and for the last article in the six-part series we visit some of the latest and greatest places for urban agriculture in the United States. Click through to see all!

Gotham Greens — New York, NY

These pioneers of commercial rooftop agriculture are expanding at a phenomenal rate. Their first farm, a 15,000 square foot greenhouse on top of a warehouse in Brooklyn built in 2010, was the first of its kind in the country. Last year, they opened their second facility, a 20,000 square foot greenhouse on top of a Whole Foods Market, which is capable of producing over 200 tons of fresh greens and hydroponic tomatoes each year. Once their most recent project in Queens comes into production later this year, the three sites will be churning out nearly a million tons of produce annually on a mere 2.25 acres in the most densely populated city in the country. The success of Gotham Greens proves the potential for urban agriculture to provide for a large portion of the food needs of city dwellers.

Wheat Street Gardens — Atlanta, GA

The flagship farm of Truly Living Well Center for Natural Urban Agriculture is an inner city oasis atop the concrete slabs of a demolished housing project in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward. The brownfield site is not suitable for growing in the ground, but the concrete foundations make an ideal platform for raised beds, which cover much of the 4-acre site. Other areas are planted with fruit trees and berry bushes, which together with produce from the center’s other farms scattered about the city, supply a weekly farmer’s market on site and a year-round CSA.

Beacon Food Forest — Seattle

Seattle has always been known as a haven for urban agriculture and boasts the second largest community garden network in the country after New York City. In the last year, however, a new form of community gardening has emerged from an overgrown lot in the Beacon Hill neighborhood. It is America’s first public food forest and it will soon be open for foraging. So far two acres out of a planned seven acre park-like garden have been developed, featuring multiple layers of edible vegetation from herbs and veggies at ground level to the canopy of towering nut trees.

Growing Home – Chicago

Spread across three sites on Chicago’s south side and a fourth in nearby Marseilles, Illinois, Growing Home is dedicated to providing meaningful work to at-risk groups. Founder Les Brown, who passed away in 2005, left a legacy of service to Chicago’s homeless population, who continues to be the primary recipients of the farm’s educational and job training programs. Growing Home bears the proud distinction of being the first certified organic farm in the city of Chicago.

Images Via Gotham Greens, Truly Living Well, Beacon Food Forest, Growing Home

Part six of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Want even more urban agriculture content? Check out our new Urban Agriculture Pinterest Board!

The Tricky Business of Zoning for Urban Agriculture

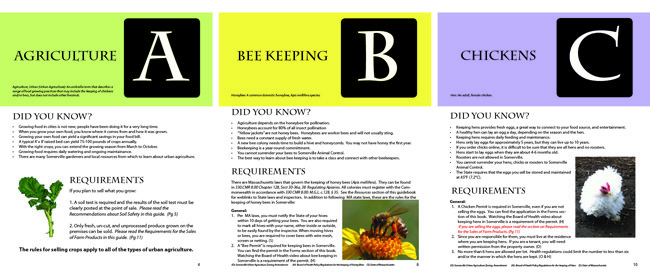

Urban agriculture is a conundrum for municipal planning agencies. The ‘Euclidean’ approach to zoning that has guided the growth of cities over the last century delineates incompatible land uses that, if not separated, could cause annoyances, health hazards and loss of real estate value. Zoning could, for example, prevent a factory from being placed in the middle of a residential neighborhood.

This type of zoning has also dictated that agricultural activities be confined to specific areas, generally on the outskirts of cities, to prevent the unpleasant sights, sounds and smells that are associated with certain types of farming operations such as concentrated feed lots or chicken houses. Many people are shocked to discover just how restrictive zoning ordinances can be in regard to food production. In some areas, front yard vegetable gardens are against the law and chickens are still illegal in many jurisdictions. The sale of produce has rarely been a permissible ‘home-based occupation’, precluding market-based urban agriculture. There is an obvious logic to the ‘separation of uses’ rationale, but the intentions behind urban agriculture are quite different from other forms of farming and it is certainly not what previous zoning ordinances concerning agriculture have been based on. Changes in land use law take a while to catch up with changes in public interest and market demand, but there are several ways that they are beginning to change to be more accommodating to urban food production.

There is an obvious logic to the ‘separation of uses’ rationale, but the intentions behind urban agriculture are quite different from other forms of farming and it is certainly not what previous zoning ordinances concerning agriculture have been based on. Changes in land use law take a while to catch up with changes in public interest and market demand, but there are several ways that they are beginning to change to be more accommodating to urban food production.

RELATED STORY: The Challenges of Urban Agriculture: Contamination, Economics, and Management (LINK)

In general, there is a trend towards allowing a mix of uses with a recognition that the overemphasis on separating residential areas from employment centers and shopping districts has contributed greatly to suburban sprawl – enemy #1 for urban planners. The key to making mixed use districts work is effective design. Municipal planning agencies impose design standards in mixed use districts to ensure that residences, office buildings, shopping centers, and even light industry can coexist side-by-side in harmony – something that landscape architects play a large role in.

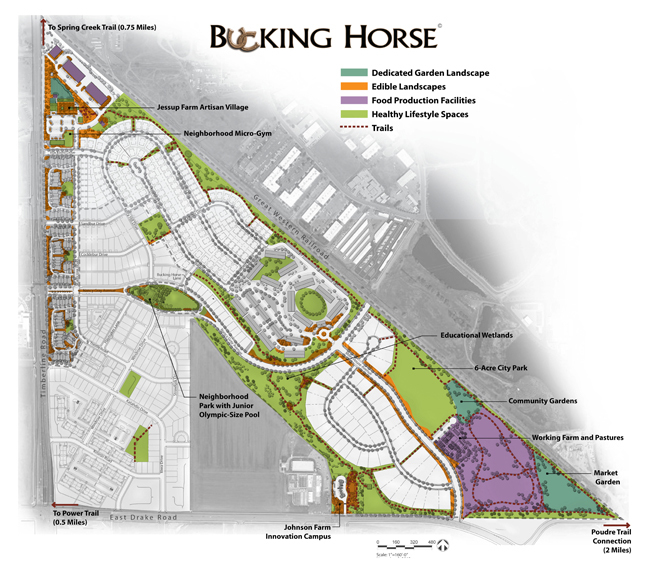

Mixed use designation favors unconventional patterns of urban development, making it one window of opportunity for urban agriculture to find its place, though there are many variations on the theme. Planned unit developments, which is essentially a mixed use district planned as a single development, are the most common. However, in principle, a landowner can petition for a zoning variance to permit agricultural uses of any property, a matter that is decided through a process of public hearings and review by the planning commission.

Mixed use designation favors unconventional patterns of urban development, making it one window of opportunity for urban agriculture to find its place, though there are many variations on the theme. Planned unit developments, which is essentially a mixed use district planned as a single development, are the most common. However, in principle, a landowner can petition for a zoning variance to permit agricultural uses of any property, a matter that is decided through a process of public hearings and review by the planning commission.

RELATED STORY: Top 4 Urban Agriculture Books for Landscape Architects

Rather than being reliant on loopholes in the existing body of land use law, many cities are now opening the door more fully to urban agriculture by adopting comprehensive zoning amendments with the express purpose of integrating it into the urban fabric. These new laws are specifically tailored the modern context of urban agriculture, spelling out exactly what types of agricultural activity are allowed where and rules for the way they are designed and operated.

In cities like Atlanta Boston, Seattle, Chicago, Minneapolis, Buffalo, Portland, San Francisco and scores of others, the local government has recognized the value of urban agriculture to make their community prosper and are using their regulatory powers to embrace and incentivize it. Landscape architects are used to following the rules of zoning and design standards in the communities where they work and now the same process can be followed for designing food-producing landscapes, taking some of ambiguity out of the process and helping designers know that they are on solid legal ground.

In cities like Atlanta Boston, Seattle, Chicago, Minneapolis, Buffalo, Portland, San Francisco and scores of others, the local government has recognized the value of urban agriculture to make their community prosper and are using their regulatory powers to embrace and incentivize it. Landscape architects are used to following the rules of zoning and design standards in the communities where they work and now the same process can be followed for designing food-producing landscapes, taking some of ambiguity out of the process and helping designers know that they are on solid legal ground.

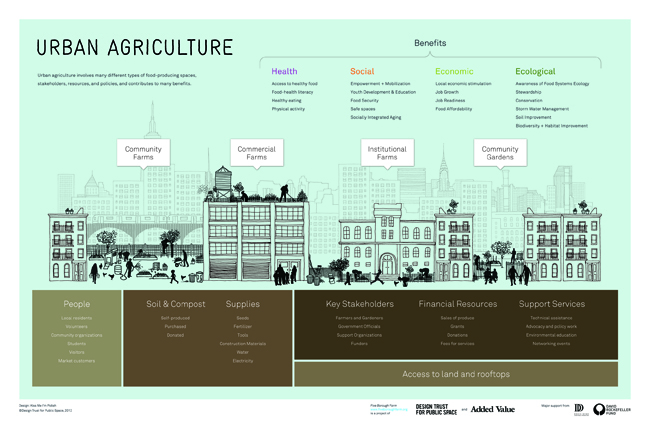

Images Via City of Somerville, Design Trust for Public Space, Georgia Organics

Part five of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Want even more urban agriculture content? Check out our new Urban Agriculture Pinterest Board!

The Challenges of Urban Agriculture: Contamination, Economics, and Management

In many ways, urban growers have the odds stacked against them, especially when compared to rural farmers. Yet, there are increasingly more examples of successful urban farming. Much of this is due to the contributions of landscape architects, who have much to offer in guiding urban agriculture towards a strong civic institution. In this post today, however, we will identify the main challenges to urban agriculture and how to remedy them.

Soil Contamination

One of the first steps needed to assess a site’s potential for food production is to have a soil test conducted. Farmers do this to determine what sort of soil amendments are needed for a particular crop, but in an urban context, the first concern is whether or not the soil is safe for food production. Toxic metals that are taken up into plant tissues can then be absorbed by the body when the plants are consumed. Lead is the most common contaminant and so, it is generally recommended that only soils with 300 parts per million or less be used for food production.

If the soil is unsuitable for growing in, the site can still be used for food production. Soilless, hydroponic methods are one option, but it is also possible to import clean topsoil and use it in raised beds. In the latter case, it is necessary to use a geotextile membrane and or clay barrier to prevent the roots from penetrating the contaminated soil. Phase one environmental assessments are needed for the reuse of most urban properties, whether for agricultural purpose or otherwise, so the particular implications for food production can be assessed as part of the process by a qualified environmental professional. The EPA has published a useful guide entitled Brownfields and Urban Agriculture that is a good starting point for understanding the issue.

RELATED STORY: Love Your Soil: What I Learned from ASLA 2013

Economics

Unless the most sophisticated methods of aquaponic (fish and vegetable) production are used, it is difficult for agriculture to provide the same return on investment in developing urban land as building residences, retail districts or other typical urban uses. Thus, food production is generally an accessory to one of these other uses, much like landscaping and parks — they contribute indirectly to the value of real estate by making the places where we live and work more enjoyable.

RELATED STORY: Putting a Price on Design: What is the Value of Public Space?

Food-producing landscapes generally have higher operating costs, as they are inherently high maintenance. However, the typical notion of landscape maintenance as a line item in the annual budget is not entirely appropriate in this context. These are working landscapes, meaning that the ‘maintenance’ activities of weeding, tending and harvesting are what fulfills the purpose of the design. The point is that landscape architects must work with their clients to devise successful programming for urban agriculture sites that will make ‘maintenance’ a built-in part of the project.

Management

If the site has a primarily educational purpose, proceeds from hosting classes and workshops can pay a master gardener or farmer to oversee the property. If the site is an amenity to a residential development, the HOA fees have to be structured to pay for the operational costs. In some cases, an individual may be given free access to the land in exchange for running their own farm on it, selling the produce they grow and running it like any other business. The landowner benefits by having the land used productively — and in a way that equates to a value-adding amenity — and the farmer benefits from the low rent and the close proximity to markets for their produce.

Landscape architects may not need to be involved in brokering all these arrangements, but the more they involve themselves in the overall process of making urban agriculture a viable endeavor, the more it will serve to make the landscape a focal point in the urban agenda.

Images via Wikimedia, Wikipedia.de, Bellisimo, LizzyPhoto

Part four of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Want even more urban agriculture content? Check out our new Urban Agriculture Pinterest Board!

Food-Producing Landscapes: Principles of Design

Food producing landscapes are more controversial than your typical landscape project. As mentioned in a previous post, urban gardens often trigger a sense of environmental stewardship from people, but successful design is key to public acceptance. Urban agriculture is an umbrella term for the many different contexts of food production that occur outside the typical context of rural farms — food gardens for residential properties, community gardens and market scale farms to name a few — each of which has very different user needs. However, a common set of principles can help guide the design process for any of them.

Aesthetics

1) Use hardscape features to create aesthetic definition.

The clean lines of paths, patios, fences, raised beds, retaining walls, arbors, trellises and pergolas can all be used to create order out what can sometimes be a chaotic and cluttered plantscape. Fruit trees espaliered along a rigid structure (i.e. wood or wires) or a turning a hillside into a terraced vineyard are examples.

2) Maximize ornamental characteristics of edibles.

The aesthetics of edibles have much to do with how they are trained, pruned and cared for. A well-pruned fruit tree or grapevine can be truly stunning. However, some edibles have much higher aesthetic qualities than others, making them good candidates for high profile locations in the landscape. These include shrubs like blueberries and pomegranates; vines such as grapes and kiwis; trees like Asian persimmons and apricots; and vegetables such as rainbow chard, colored lettuces and eggplant.

RELATED STORY: Downtown Detroit Springs to Life with Lafayette Greens

3) Choose an appropriate aesthetic motif.

Food producing landscapes lend themselves to informal styles. They are intended to be entered and worked in, more than viewed. Thus, sleek modernist or minimalist approaches are generally not the way to go; a ‘workshop’ garden environment highlighted with natural stone and post and beam structures of rough-sawn timbers or weathered iron is a better fit.

Function

4) Treat the soil and plantscape as a living system.

Incorporate nitrogen-fixing groundcovers and hedges to help replace some of the nitrogen lost in the harvest and maximize the use of free-flowering perennials (rosemary, bee balm, lavender, yarrow, etc.) to attract and harbor the beneficial insects that help keep pest populations in check. Water features should be in the form of pond and wetlands for amphibian habitat (another form of pest control), rather than sterile fountains.

5) Integrate outdoor dining/gathering spaces.

Urban agriculture is about the cycle from food to plate, making it important to design for events and celebrations. Pizza ovens, outdoor kitchens, picnic tables and room for crowds are design elements to consider.

RELATED STORY: Why Landscape Architects Stopped Specifying Edible Plants (And Why They Have Started Again)

6) Plan for the unique functional requirements of food-producing landscapes.

Storage for tools and equipment, compost facilities, specialized irrigation systems, greenhouses, livestock quarters, processing areas and farmstands are typical components of ‘working’ landscapes that are slightly different than what typically falls under the purview of landscape architecture. They are all relatively simple to design in and of themselves, but putting them together into a cohesive, functional plan can require a lot of homework on the part of the designer.

7) Think vertically.

Urban agriculture is about maximizing food production in small spaces. From training vines on fences, walls and other support structures to layering edibles in the canopy, shrub and ground level plantings and exploring the use of greenhouse aquaponics systems, the potential to increase yield is largely up to the ingenuity of the designer.

Intangibles

8) Utilize interpretive elements to engage users.

Signage can be a very tacky design feature, but it in the case of edible landscapes it can really help the public to engage with what they are seeing. In addition, the creative use of food- and agriculture-themed symbolic elements — artwork, repurposed farm implements or stylized irrigation channels, for example — can go a long way toward creating food-producing landscapes that are rich with meaning. Urban agriculture is as much about the connection to food as it is about growing food.

9) Collaborate with specialists when needed.

Landscape architects are used to hiring sub-consultants like civil engineers and lighting designers, but a different set of specialists are in order when designing urban agriculture sites. The list in #6 above hints at some of the areas where this may come up, but there are also technical applications like aquaculture and hydroponics where the assistance of a specialist will almost certainly be in order.

10) Mitigate liabilities with barriers, signage and management strategies.

Safety in regards to things like bee hives and farm implements is crucial on urban farms, which may need to be secured after hours for these reasons. There is also liability in inviting people to eat what is planted and landscape architects have to work with their clients to create physical interventions or other means to prevent unintended negative consequences.

Images via Ken Weikal

Part three of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Want even more urban agriculture content? Check out our new Urban Agriculture Pinterest Board!

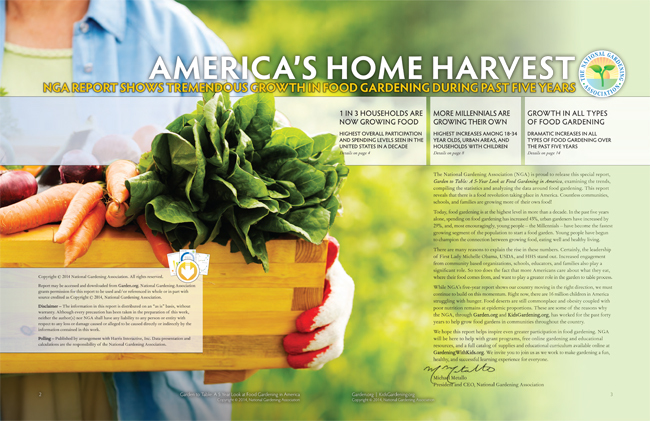

The Beauty of Food: Gardens As Placemakers

According to a recent study by the National Gardening Association, more than 1 in 3 American households now grow a portion of the food they consume — a 17 percent increase over the last 5 years alone. For the 18 to 34 age group, the statistics show a staggering 63 percent increase in food gardening in the same time period. The popularity of food gardening has led the practice out of the realm of a backyard hobby, and into the popular public realm, where it is now an important subject for landscape architects to attend to. Food gardening has become a marketing phenomenon that benefits the profession, but it also gets at the root of what landscape architecture is about: stewarding the relationship between humans and the environment.

Architect and urban planner Andres Duany has described food gardens as the new “social condenser.” He believes that the Great Recession caused a fundamental shift in cultural values where consumerism has less primacy as a driver of decision-making at a household level. Instead of mass consumerism as the venue for social interaction and community building, Duany says that food — its cultivation, harvest and enjoyment — is coming to define the public realm in America.

The ‘diseases of excess’ and other health epidemics that stem from the sedentary lifestyle and industrial style of agriculture that predominates in developed countries has led us to realize the tremendous benefits of locally-grown and naturally produced food. Urban agriculture addresses issues of public health, the environment and urban decay in one package. The practice transcends cultural, class and religious lines, making it a natural fit as a community centerpiece that people from all walks of life can support.

RELATED STORY: 5 Urban Agriculture Films to Get your Hands Dirty

Food production engages people with the landscape in a very different way than a typical park, front yard, urban plaza, streetscape or other domain typically designed by landscape architects. Instead of just enjoying the way a place looks, we are drawn into the environment through smells, flavors and curiosity about the journey from seed to fork. The landscape ceases to be a static backdrop for life and is transformed into a source of sustenance, not just physically, but spiritually and emotionally. Spending a few hours a week working the soil, tending to plants and nurturing forth a harvest is a priceless form of therapy for urbanites accustomed to a routine of commuting, working in an office and buying all their food in grocery stores.

In his book, Garden Cities: Theory and Practice of Agrarian Urbanism, Duany describes the way land use is being altered by this paradigm shift and lays out a vision for incorporating food production across the ‘urban transect’ from the suburban fringe to the downtown core. How much production will actually supplant consumption in urban areas remains to be seen. But there is ample evidence for the value of community gardens, city farms and urban homesteading in bringing people together and creating that elusive, difficult to define, but incredibly magical quality that we call ‘a sense of place’ — the feeling that all landscape architects hope to nurture in the places they work.

Images via Flickr, National Gardening Association and Ken Duret Photography

Part two of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Want even more urban agriculture content? Check out our new Urban Agriculture Pinterest Board!

Why Landscape Architects Stopped Specifying Edible Plants (And Why They Have Started Again)

In the 150 years that landscape architecture has been formally recognized as a profession, there has existed a gulf of separation between our discipline and agriculture. Even though plants, soil, and people are fundamental to each field, the former focuses on aesthetics and the structural functions of human settlements (drainage, access and circulation, integration with the built environment, etc.), while the latter is centered on the process of cultivating edible species for consumption. Recently, however, there are signs of integration between the two disciplines and landscape architects are now being challenged to adopt new methods to mitigate the discord between them.

Lafayette Greens Community Garden in Detroit, MI via Land8

In many ways, environments designed by landscape architects are the antithesis of the utilitarian landscapes designed and managed by farmers. As industrialization and urbanization progressed in the 19th century, agriculture was increasingly viewed as an occupation of lower class and uneducated people–city people often considered the work beneath them. While the local food and urban agriculture movements have started to turn that notion on its head in recent years, there are still major barriers for landscape architects in designing productive landscapes. Here’s why:

Management

A ‘crop’ makes an urban landscape more complicated to manage and maintain. Landscape architects are reliant on the landscape maintenance industry to makes sure that what they design develops as it was intended over time, but maintenance companies are generally not geared to care for edibles, which require specialized horticultural knowledge to succeed. This also adds to the operating cost of a productive landscape, though in theory this can be offset by income from the harvest. There is also the issue of fruit drop and other ‘messy’ habits of edible plants that landscape architects are trained to steer away from.

Liability

Landscape architecture is a highly regulated profession charged with protecting the health, safety and welfare of the public through the design of the outdoor environment. Landscape architects are taught to avoid specifying trees like pecans and walnuts near any sort of hardscaping, as their fallen nuts are like marbles on a sidewalk and can create a hazard for pedestrians that landscape architects are then potentially liable for. Including edibles in the landscape presumes that people are invited to harvest them, but what if someone gets sick? What if a child climbs a tree to harvest an apple and falls? If an edible landscape is extended to include bees, chickens, fish, goats or other livestock, these concerns are amplified even more. The protocols for landscape architects to navigate these design challenges are not clearly defined, which makes urban agriculture seem like a pursuit laden with risk.

RELATED STORY: Urban Agriculture: 8 Landscape Architecture Firms Leading the Way

Aesthetics

There is a common perception in the general public that edible gardens lack aesthetic beauty. In turn, many landscape architects are reticent to push the envelope for fear of backlash from their clients. It is true that many edibles, especially annual vegetables, can have a rangy and unkempt appearance, particularly toward the end of the growing season. There are also fewer options for choosing just the right colors, textures and forms in edible plant material than there are with the tremendous array of ornamentals that breeders have developed. In general, edibles are contrary to the notion of the ‘architecture’ part of landscape architecture, which implies a relatively static appearance compared the dynamic nature of food gardens.

Despite the complications of designing food-producing landscapes, there is now tremendous public interest in urban agriculture. People value the many benefits of healthy, local food and are hungry for the experience of cultivating and harvesting. Urban agriculture is becoming an institution and landscape architects are increasingly called upon to design aspects of these environments. Over the next five weeks, we will explore the ins and outs of designing productive landscapes and, in the process, explore strategies for overcoming the historic rationale for not using edible species.

Part one of a six-part series on urban agriculture

Images Via Trinity Avenue Farm and Wikipedia

NYC’s High Line Park Celebrates 5th Anniversary

When Frederick Law Olmsted unveiled his plans for Central Park in 1858, the young profession of landscape architecture made its debut onto the world stage. Few projects since then have made such an impact on the meaning of parkland until the opening of the High Line five years ago this month.

The 1.45-mile linear park (1 mile completed to date) has literally ‘elevated’ the concept of integrating cities and nature to mainstream status. Where Olmsted established the notion of a municipal park system to serve the needs of city dwellers to enjoy the outdoors, James Corner and his cohorts have proved that the natural and built environment can co-exist on an even more intimate basis.

This seamless meshing of architecture and nature has long been a vision of landscape architects, but it took the pro-urban sustainability agenda of ex-mayor Bloomberg, the remarkable creativity of the design team and the recognition by the community that pulled together a project to demonstrate this principle in a meaningful and lasting way to a global audience.

The High Line story goes back to 1934 when it was built to replace the existing street level freight line running through New York’s industrial core on the Lower West Side. By elevating the railway, conflicts with vehicular and pedestrian traffic would be eliminated and the rail structure could be integrated directly with the factories and food processing plants that relied on it.

The vertical expansion of urban infrastructure made sense to city planners 80 years ago and the idea has now been transposed to another context: greenspace. Instead of delivering timber, iron ore, produce and livestock to be processed into commodities for distribution to the world, the re-purposed High Line moves New Yorkers to and from a network of condos, office buildings, shops, restaurants, galleries and event venues along a green swath of hanging gardens and spreads the vision of pedestrian-dominated cityscapes to the world.

Beginning in the 1950s, the predominance of interstate trucking in the freight industry drove the High Line into obsolescence by the early 80s. The plants that colonized the gravel bed of the abandoned tracks later became design inspiration in its reincarnation as a park. Left to its own devices, nature always creeps into cities in an attempt to initiate the process of natural succession that landscape architects must take stewardship of.

Rather than wiping the slate clean and imposing sterile new infrastructure, the High Line is a prime example of working with the forces of nature and harnessing their ability to improve environmental quality and the quality of human life. It is an expression of the sentiments behind green rooftops, living walls and vertical farms manifested artfully and eloquently in New York City, a global hub for leading innovation and culture. The High Line has helped boost landscape architecture from relative obscurity to one of the leading practices increasingly looked to for solutions to the biggest challenges of the 21st century.

Friends of the High Line celebrated the 5th anniversary of the High Line yesterday at the Pie In the Sky event that offered free pie and lemonade all day. You can join in the celebration of this momentous occasion by attending their tours, events, and the highly anticipated 2014 Summer Party on the High Line kickoff later this month.

Images Via Wikipedia