Author: Stephanie Roa

Conflict Wood [Video]

The use of tropical hardwood lumber, such as ipe, in construction is damaging the world’s ecosystems at an alarming rate. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Austin, Texas, Zac Tolbert, a licensed landscape architect and Business Development Representative at Delta Lumber & Millworks, outlined the detrimental environmental impacts of specifying tropical hardwoods and the sustainable alternatives available. As a call to action, Tolbert urged design professionals to be stewards of nature and lead the building and construction industry to a sustainable future – starting with eliminating the use of tropical hardwoods in their projects.

While wood is considered a renewable resource, standard harvesting practices such as clear-cutting, in which large expanses of forests are cleared, do not allow true renewal of the resource because harvesting outpaces renewal. This practice is resulting in a vast amount of deforestation, the destruction of valuable habitat, and the displacement of indigenous peoples. A 2014 Greenpeace investigation of logging in the Amazon rainforest determined that the Amazon is disappearing at an alarming rate of one acre per second, resulting in an 18% loss in the last 30 years. The study also estimated that in Pará, one of Brazil’s main logging regions, 78 percent of hardwood lumber is harvested illegally.

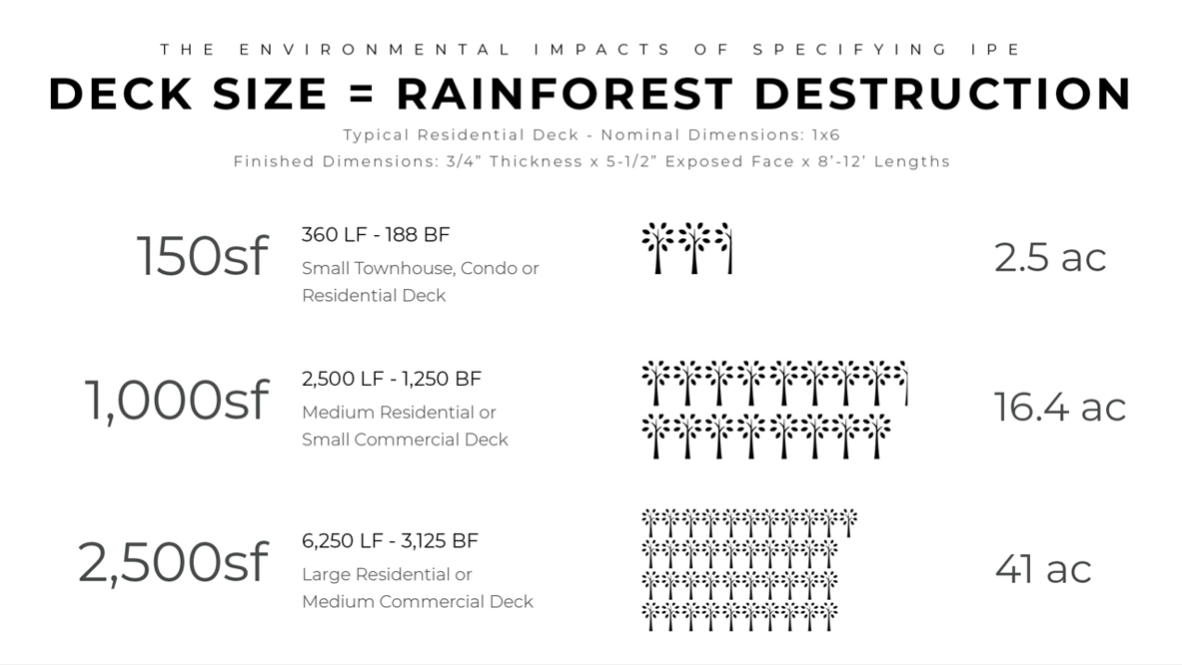

Tropical hardwoods are so durable and decay-resistant that they appear to be the ideal material, yet the environmental impacts of using such hardwoods – even those certified by the Forest Stewardship Council – are well-documented, threatening the most critical ecosystems of our planet. Tropical hardwoods are sourced from highly sensitive regions and often retrieved through rainforest deforestation or illegal logging practices. Furthermore, despite seemingly desirable hardness, their slow-growing nature (growing merely 0.5-0.7 CM in DBH per year for a 100 year maturity rate) and narrow form makes them a poor timber species, while their susceptibility to significant movement and shrinkage are a major liability concern. Due to this, harvesting ipe is highly wasteful, with an estimated 85% of ipe timber wasted during logging. Tolbert estimates that just a 150 square foot ipe wood deck with 8-foot long boards results in 2.5 acres of rainforest destruction.

Tolbert’s message is clear: stop trading in rainforest for luxury. Fortunately, alternatives do exist – and their durability and resistance to decay outperform that of tropical hardwoods. In the last decade, we’ve seen a significant improvement in wood modification technologies come to the U.S. market. These technologies use physical, biological, or chemical processes to produce property improvements in softwoods and U.S. hardwoods. If you want the strength of tropical hardwoods without enabling further tropical forest degradation, modified wood is the perfect alternative.

Thermal Modification

Thermal modification uses heat to remove organic compounds from the wood cells, so it will not absorb water, expand, contract, or provide nourishment for insects or fungi. The high heat produces a naturally durable wood that is permanently resistant to water, insects, and decay. Because the wood is not absorbing chemicals to be treated, but rather removing moisture, the wood is lightweight. Thermally modified lumber is also more dimensionally stable because it is less susceptible to cupping and warping. The wood has increased heat resistance and weather resistance as well. When properly maintained, it will not chip, rot, or warp over the years. Many products offered in this category are rated for 20 or 25 years of exterior use. Thermory, a thermally-modified wood manufacturer, believes that they can be part of the solution to illegal logging and rapid climate change by offering an alternative to rainforest wood with better performance.

Polymerized

Kebonized lumber is impregnated with extracts from plant biobase and cured to polymerize the wood at the molecular level, which reduces shrinking and swelling by nearly 50% while significantly increasing its density. Developed in Norway, Kebony is the main manufacturer of polymerized lumber, using a patented process to enhance the properties of sustainably harvested softwood, giving Kebony premium hardwood characteristics while remaining environmentally friendly and sustainable. Kebony wood also provides a high level of safety as the wood does not splinter and contains no toxins or chemicals, while maintaining a rich brown color throughout that naturally patinas over time. With a 30-year warranty, Kebony is a beautiful alternative to traditional tropical hardwoods.

Acetylated Wood

Acetylation is subjecting a softwood to a vinegar, which turns it into a hardwood by preventing the cells in the wood from being able to absorb water. Treated in the Netherlands, Accoya is the main acetylated wood supplier to the United States. Accoya timber has been modified by a process called acetylation, which increases its durability while enabling it to resist rot and stay strong. The acetylation process uses acetic anhydride and heat to modify wood’s composition, reducing the wood’s ability to absorb water and rending the wood more dimensionally stable and durable. Made using fast growing, sustainably forested radiata pine, Accoya is a non-toxic, biodegradable product that is 100% recyclable. With a 50 year above ground warranty and a 25 year warranty in ground or freshwater, Accoya provides long-lasting guarantee.

Wood modification technologies have made a historical shift in the availability of products that can outperform tropical hardwoods while causing no harm to the environment in the process. As landscape architects and specifiers of wood decking and site furnishing, Tolbert reminds us to be conscious in our product selection. Together, we can control the demand of illegally harvested, unsustainable woods by eliminating the use of them in our designs.

—

This video was filmed on June 25, 2019 in Austin, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

The Icon: From Concept to Reality [Video]

Iconic elements in the landscape – whether sculpture, public art, or branded graphics – accentuate the experience of a place. These “icons” become identifiers that capture the character of a place and act as a physical interpretation of a development’s brand. However, sometimes the intention of such placemaking icons can fall short, as ideas conceptualized early-on in the design visioning process are not fully realized.

How can designers ensure an initial design vision is carried through to implementation? To answer this question, Alex Ramirez, Office Director at Design Workshop’s Houston office, formed a research group with his fellow coworkers as part of Design Workshop’s Emerging Leaders Group* program. During his presentation at the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Houston, Texas, Ramirez, spoke about his team’s process and their findings.

Joined by a shared interest in placemaking “icons”, the research group endeavored to identify the necessary steps to successfully integrate such elements into their projects. Ramirez’s team began by brainstorming developments that have iconic elements and researching the design teams behind these projects. Once firms were identified, the team scheduled informal interview with members of each firm to understand the successes and shortcomings of their process.

Through these conversations, Ramirez’s team was able to distill the steps and procedures needed to get an iconic element built successfully, including when to engage an artist, what materials to consider in construction, and what programming requirements to discuss with the client. As their final product, the team created a step-by-step diagram to be referenced by the design staff at Design Workshop on future projects, ensuring the right steps are taken throughout the planning and development process.

In closing, Ramirez encouraged his fellow design professionals to always remain open and willing to ask questions, reminding the audience that “vulnerability breeds innovation”. In order to achieve their goal, Ramirez’s team needed to recognize their knowledge gap and be willing to request advice from experts on the topic.

*To facilitate thought leadership and meaningful research among young staff members, Design Workshop created the Emerging Leaders Group, which brings staff together over a topic of shared interest. The program has generated a number of noteworthy resources for the firm, including the publication “Landscape Architecture Documentation Standards: Principles, Guidelines, and Best Practices” which received an ASLA Professional Honor Award in 2016.

—

This video was filmed on June 26, 2019 in Houston, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

What Automation Means for Landscape Architecture Practice [Video]

We are in an era of digital transformation. The emergence of new technologies is rapidly transforming the way we approach design, with firms utilizing computer software more heavily than ever before. Does this mean the jobs of landscape architects are soon to be replaced by automation? Probably not, but it will challenge us to do things differently. Formerly of Clark Condon at the time of this video and now as Senior Associate at TBG Partners, self-proclaimed “tech nerd” Chris Gentile put it, “In order to maintain relevance, we must adapt.”

At the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Houston, TX, Gentile explains why he has embraced automation, not only for its efficiency, but also because it frees up time for more creativity in the design process. Recognizing the benefits, TBG Partners is investing in automation technologies to improve design workflow, drive better decision making, and gain a competitive edge. I caught up with Gentile recently to see how he, as Digital Technology Manager, is leveraging automation and what advice he has for others.

Describe your role as Digital Technology Manager at TBG Partners and how you became interested in digital automation.

[CG] My current role at TBG as their Design Technology Manager reflects the investment TBG is making in technology. Design Technology is an emergent field in architecture, let alone being talked about in landscape architecture. It’s a risk journey, but I’m excited for what’s ahead. Firms that are dedicating these roles understand how they can leverage discoveries in technology to expand their portfolio to include more complex and rewarding work. TBG is forging that path.

I help navigate the firm through its digital landscape. I typically work with focused, cross-functional teams to discover and explore new technologies and how they can make us better. I support the goals of these teams by developing an improved user experience with tools and workflows operating across multiple platforms.

My interest in automation matured from my curiosity in technology. I never settled for the status quo and it frustrated me to do things inefficiently. As I mentioned in the Land8x8 talk, I had that voice saying “there’s got to be an easier way”. I took the path of doing the hard thing once – automating the task – rather than doing it the “easy” way a hundred times.

In your presentation, you encourage landscape architects to embrace digital automation. How has automation changed your approach to design and what opportunities will automation provide the profession?

[CG] I leverage automation more and more on every project I work on. It was real-world experimentation that eventually matured to something formal and eventually transformed the entire production workflow. It started simple with project-specific scripts but grew quickly to be dynamic and applicable for any project. There was a lot of effort involved to make that happen.

From my exposure to programming, my approach to design is more computational and rooted in systems thinking. I detach myself from the actual form of an object and focus on crafting the idea of how objects are managed and how they interact with each other. I am often surprised by the solutions; things I never would have thought of using traditional methods.

Automation provides professionals more time to think critically rather than spending their time on laborious, button-pushing tasks. Especially for young designers that are positioned to burden such roles, automation can allow them to fast-track their professional development as landscape architects.

Now that so many software choices are available to landscape architects, how do these new tools change what landscape architects do?

[CG] There’s a lot out there, and with landscape architecture lacking a majority in the AEC industry, we’re at the mercy of tools developed for other disciplines. As with our role in the design, we typically act as the middle man between many of them. We need to be aware of the platforms architects and engineers are using, how they fit in with the way we work and ensure interoperability amongst the many platforms that are being used.

BIM is requiring us to fit into a common data environment where this data sharing is critical to downstream workflows. The greater dimensions of BIM are aspirational for landscape architects now, but it’s where we need to be aiming to be relevant in the future. Landscape architects are behind the curve compared to what architects and engineers are doing today when it comes to BIM – that shouldn’t be news to anyone.

How might technology drive better design?

[CG] I love debating this question because technology doesn’t drive better design – that’s the responsibility of the designer to provide quality or value. Earl Broussard, TBG’s outspoken founder, says technology allows us to make mistakes faster and process things quicker. That processing part is what drives better design; the technology just allows it to happen. At the end of the day, what ends up on paper is a human decision.

What efficiencies have you discovered in automating the documentation process?

[CG] Documentation is best suited for automation, it’s a whole lot of work with fairly consistent procedures. One example I can share is a tool I developed in CAD to assist with grading – not to do grading, but to assist. You still have to know how to grade and all the constraints associated with it.

The traditional method for grading is manual – you plot out a plan, get your scale, calculator, and coffee then start grading. If there’s a grade bust, you go back and find another solution. In Houston, grading can be tricky because it’s so flat; even a small inaccuracy on your calculations can compound and cause problems. It’s one of the most iterative processes in our scope of work.

So to expedite this process, I built this tool inside CAD that follows the same logic I would on paper but with the greater precision of CAD and the calculations were automatically computed avoiding the human and precision errors that exist in the manual process. The tool prompts you between each input to find the missing variable in the slope formula, then allows you to interpolate. I used it every time I graded.

The misunderstanding people have with automation is they think it does the whole job – it doesn’t; it can’t think for you. The grading logic in this example is guided by the user; the tool just makes it easier to get the job done.

Chris Gentile

Have you discovered any barriers that inhibit integrating automation into practice?

[CG] Plenty! As I mentioned in the previous answer, there’s a gap in understanding what automation is. There’s the fear that associates automation with deskilling. From the previous example, this fear was having designers not knowing how to grade. Communicating the greater outcome or opportunity of automation is key. To borrow Earl’s antidote, this tool will allow us to make mistakes faster and process things quicker.

Duration is another barrier – turning a one or two day task into a 20-minute step doesn’t happen overnight. There is a lot of discovery and failure in process optimization. The hard part is to find where to start because it can be overwhelming. For me, I have to be able to get my arms around the larger workflow before seeing ways to make it better and how that optimization fits into the greater design process.

Similarly, firms need to take optimization seriously – it shouldn’t be treated as a side project. All firms want efficiency, but not all firms are willing to commit non-billable time to it – you have to take that leap of faith and make the financial investment.

What are some basic steps every landscape architecture firm can take to better incorporate technology into their design and implementation process?

[CG] I’ll share what TBG’s CTO, Greg Nichols, told me: celebrate technology – test things, break things, learn things. Technology touches all parts of your business operation. If you’re thinking about it as just a CAD tool, you’re not thinking of it right.

For me, I treat my projects as if they’re startups – that’s the entrepreneurial mindset in me I guess. These tools have the same uncertainty of success, so developing and assessing their value with the same scrutiny tends to steer them towards being successful.

The first step is knowing where you are today – establish a baseline. What’s your measuring stick? Make sure these measures can be clearly understood, provoke action, and that the data is transparent. Subjective measures are hard to gauge success with.

Next, create a feedback loop. With anything new, you’re assuming people will change their behavior in the way they use it. How are you going to validate the tool is being used as you intended? From what you learn, tune the engine – make tweaks, and test new ideas.

Learning is key in the process and failure is a common learning moment when you develop anything new, so don’t be afraid to fail. Much of what we do can and should be automated. Today, our design medium is more complex than ever, yet we’re still treating it like pen and paper – there’s got to be an easier way to do this.

—

This video was filmed on June 26, 2019 in Houston, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Evoking Soul in Landscape Architecture [Video]

There has been a trend in landscape architecture to measure the success of a project using research and quantified data. However, to Christine Ten Eyck, founding principal of Ten Eyck Landscape Architects (TELA), evaluating the success of a project extends beyond quantifiable metrics and measurable outcomes. Ten Eyck defines successful projects as places designed with “soul” – those that people connect to on a deeper, more meaningful level. Soul – the inspiration, feeling, emotion, passion, spirit and energy of place – is that added sense of surprise and delight that brings meaning to a space. When you design a landscape with soul, every detail has a purpose and the use of texture, vegetation, and water form a dialog between beauty and functionality. During her presentation at the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Austin, TX, Ten Eyck reflected on those projects throughout her career that evoke soul.

From private residences to public parks to university campuses, TELA has a vast portfolio, tied together through a sensitivity to place. Based in Austin, Texas since 2007, and previously in Phoenix, Arizona, their projects respond to local context, celebrate native ecologies, promote water conservation, and utilize local materials to create enriching, high-performance landscapes that address pressing global issues such as drought, climate mitigation, and aging infrastructure. Through place-based landscape architecture, Ten Eyck strives not only to address these complex, locally-specific environmental challenges, but also to create places that connect people with their surroundings, foster human healing, and, of course, evoke soul.

Steele Indian School Park; Image: Place Landscape Architecture

Steele Indian School Park is a 72-acre public park in central Phoenix that leverages the site’s somber yet sacred history to create a historically-immersive urban park experience. Formerly the Phoenix Indian School, a boarding school founded in 1891 as part of the federal “assimilation” policy that sought to re-educate and culturally assimilate Native American children, the park design honors the site’s Native American history while celebrating its contemporary context. Originally used to suppress their tribal traditions and identities, the site now celebrates the individuality of the Indian identity, educating visitors on the rich history of the region.

Many of the design elements reflect Native American concepts of life, earth, and the universe. The park design includes an extensive network of paths, gardens, amphitheaters, lawns and recreation fields, and a series of interconnected water features that recall Phoenix’s history as the ‘City of Gardens’. Featuring a sunken spiraling walkway, the 15-acre Entry Garden – made of recycled concrete slabs from the paths on which Native American schoolchildren once walked – serves as an entry monument and modern-day labyrinth meant for contemplation and meditation. Visitors can decompress as they gradually descend, surrounded by the beauty of native desert plants adorning the path, until they meet the central water cistern. Etched into the concrete around the cistern is a Native American poem that explains the design theme of the park – one of several poems inscribed throughout the garden. On a recent visit, Ten Eyck witnessed a Native American family blessing their newborn child in the cistern, a tribute to the project’s successful attempt to reclaim the space for Native American celebration and tradition.

Kingsbury Commons; Image: Ten Eyck Landscape Architecture

Ten Eyck hopes to have the same success at Downtown Austin’s Kingsbury Commons, a 12-acre revitalization project that aims to catalyze the redevelopment of one of the city’s oldest public parks, Pease Park. Kingsbury Commons will be a new gateway to Pease Park, serving as a welcoming front door to the residents of this rapidly growing city. As the recreational heart and cultural soul of Pease Park, Kingsbury Commons will celebrate the park’s rich history and existing natural features, while integrating fresh, new elements to position the park for a sustainable future.

Kingsbury Commons; Image: Ten Eyck Landscape Architecture

Winding throughout Kingsbury Commons will be a low limestone ribbon wall, winding throughout the entire lower seven-acres of the park at varying heights, acting at times as a wall, seat, step, gateway, and interpretive element. Through community outreach, the design team sought input on the history, environment, and geology of the parkland and then coupled it with input from scientists, historians, and other local experts to create the language for the interpretative ribbon. Throughout the ribbon, text and prints will tell the story of Pease Park, forming personal connections to the significant stories and meanings inherent in the space. By folding this interpretive element into the natural environment, TELA aims to preserve and enhance the naturalistic feel of the park, while instilling a deep community connection that inspires future generations.

—

This video was filmed on June 25, 2019 in Austin, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Creating Binge-Worthy Nature: Rediscovering How Children Play in Nature [Video]

When you think back on your happiest childhood memories, you probably think about playing outside. Those long summer nights camping in the backyard, catching fireflies, and climbing trees are among my most vivid adolescent memories. Not only did these experiences create happy memories, more and more studies show that they provided countless mental and physical health benefits too. Nature creates a unique sense of wonder for kids that no other environment can provide. However, in part due to the influx of technology, there has been a recent shift in how children spend their free time, often replacing outdoor time with screen time. The average American child is said to spend 4 to 7 minutes a day in unstructured play outdoors, and over 7 hours a day in front of a screen. How can we create “binge worthy” play environments that encourage outdoor play and expose children to the benefits of nature? During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Houston, TX, Meade Mitchell, Principal at TBG Partners’ Houston office, shared how his firm is rethinking play environments to change this downward trend and reconnect children to nature.

Recent studies have exposed a myriad of benefits that both children and adults receive by spending time outdoors, proving that there are real physical, mental, and social benefits to outdoor play. Kids who play outside are healthier, perform better academically, and have higher self-esteem and lower levels of stress. They also tend to be more creative, more social and cooperative with others, and feel better connected to nature. Direct exposure to nature is essential for healthy childhood development. Moreover, kids who play outside have a healthier adult life, resulting in a longer life span. Unfortunately, children’s exposure to nature is plummeting, and as children spend less time playing outdoors, many are missing out on these benefits.

Image: TBG Partners

Research from the National Trust shows that children are playing outside for an average of just over 4 hours each week, compared to their parents’ generation who spent an average of 8.2 hours outdoors per week. The hours spent outside playing in local parks, exploring the woods, and building forts have been mostly replaced by playing video games and watching television. We have traded green time for screen time — and it has had a serious impact on our kids’ well-being. In 2005, author Richard Louv brought the detrimental impacts of decreased childhood exposure to nature into the public’s eye with his book Last Child in the Woods, where he coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” to highlight the health costs of children’s isolation from the natural world.

As a father of four children, Mitchell has witnessed first-hand the generational change in children’s relationship with the great outdoors. As a landscape architect, Mitchell believes that he has the responsibility to change the statistics and encourage kids to play outside. To accomplish this, he needed to learn how to entice children to the outdoors and keep them entertained for longer. He needed to make the little time kids spend outside count, and endeavored to saturate play spaces with experiences that activate all senses.

As a solution, Mitchell suggests designers go beyond specifying traditional prefabricated plastic play structures and turn to nature play, which encourages active engagement with the natural environment. Mitchell asserts that even the most elaborately designed play structures of metal and plastic do not compete with immersive natural environments. Nature play experiences often include features like real wooden logs and boulders for kids to balance and climb on, sand patches or sticks for building, native plants for critter explorations, and direct access to water to watch sunbathing turtles and skip rocks. By incorporating the surrounding landscape and vegetation, nature play brings nature to children’s daily outdoor play and learning environments. Mitchell aims to combine exploration, whimsy, and education into unforgettable destinations that connect children to the natural world.

To make great nature play spaces, TBG Partners uses five areas of consideration: responsible risk taking, authentic nature (i.e. responsive to local context), productive engagement, discovery, and inclusivity. Inclusion, Mitchell notes, encompasses more than just accessibility – it also includes sensory experiences and considerations such as the play preferences of introverts and extroverts. Loose parts are often a part of nature play, inviting imagination as children combine, move, and manipulate parts. Unstructured play allows kids to interact meaningfully with their surroundings. They can think more freely, design their own activities, and approach the world in inventive ways. By providing play equipment that ranges in level of ability, children are able to attempt risks as they gain familiarity with the space, building confidence as they achieve new skills.

Believing that nature play should extend outside of playground environments, Mitchell has been taking this type of curiosity for the natural world and bringing it to the design of neighborhood parks and other green spaces. For example, Wetland Park, the signature park in the Riverstone master planned community in Sugar Land, TX, includes a mud pie kitchen, a pond with rock throwing targets, a bridge with no handrails to make it easier to watch aquatic life, logs and natural wood placed in the ponds for aquatic habitat, and a pathway of partly submerged rocks to encourage wet feet. Kids can feel the dirt, get in the water, dig in the mud, taste the cherry trees, and be immersed in nature. These types of naturalistic amenities encourage interactions and active engagement with nature, and allow children to truly feel they are a part of the environment.

The first years of a child’s experiences set the trend for the rest of their lives. As landscape architects, we have the obligation to design authentic, immersive play environments that not only benefit a child’s development, but also instill a respect and empathy for nature. By doing so, we will help inspire a conservation-minded ethos that can shape future attitudes towards stewardship, ensuring a positive future for our profession and our planet.

—

This video was filmed on June 26, 2019 in Houston, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Feeling the Weather [Video]

The weather affects us every day, but rarely receives the attention it deserves. Often relegated to small talk conversation, we downplay the many ways weather influences our daily life, culture, and health. The weather – the day-to-day state of the atmosphere generally perceived as a combination of temperature, humidity, precipitation, cloudiness, visibility, and wind – is a moment in time. However, when we move beyond a single weather event and study the weather of a place averaged over time, a pattern can be established. The climate, or the pattern of weather moments, is not as easy to perceive, but greatly affects ecosystems and communities around the world.

Falon Mihalic, founder of landscape architecture and public art firm Falon Land Studio, seeks to give form to this invisible force that impacts our lives and shapes the landscape of our communities. Using visual art, Mihalic aims to connect the weather to our changing climate in ways that spark dialogue with the public. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Houston, TX, Mihalic shared examples of her firm’s built and speculative work to walk the audience through the “why” and “how” of feeling the weather.

The weather brings out many feelings, ranging from poetic, sublime, strange, dramatic, or even tremendous. To depict the fleeting, often intangible feelings of weather, Mihalic combines art and technology, presenting climate research in a legible and accessible form. As a landscape architect, Mihalic understands the effects weather has on the landscape, often tasked with providing creative and innovative design solutions for climate challenges such as increasing precipitation, drought, and heat stress. As an artist, Mihalic attempts to translate this knowledge in a way that resonates with the public and inspires societal change.

One such project, Color Cloud, is a site-specific public art installation that celebrates the unique skyscape over Houston. Made of polychrome mesh, the installation was inspired by the breathtaking beauty of the Houston summertime storm clouds. This immersive, colorful public art installation serves as a gateway into the experience of cloud-gazing in the city. In addition to the artwork, Mihalic’s firm created a crowd-sourced map depicting the best local places for cloud-gazing. This temporary project got the neighborhood thinking about and celebrating the natural beauty of their environment.

Color Cloud; Image: Falon Land Studio, LLC

At a similar neighborhood scale, Climate Pulse is a weather-responsive light sculpture that incorporates technology to depict local changes in temperature and humidity. Sited in Houston’s Emancipation Park, this temporary installation was designed as a parametric sculpture with responsive lighting integrated into the structure. Using an algorithm that translated temperature data into colors, the sculpture emits a glow of color based on ambient temperature. At high humidity levels, the lights sparkle to warn of impending rain, bringing attention to the changing weather and climate patterns of the site.

Bayou Beacon aims to depict weather data and climate impacts on a regional scale. The Buffalo Bayou is the main river flowing through the center of Houston, Texas. The bayou has experienced many major flooding events, including Hurricane Harvey in 2017 where extensive rainfall brought the bayou to record high water levels. The surrounding communities are greatly impacted by storm surges, but their vulnerability is not always perceived. Utilizing real-time data, the art installation will showcase the rise and fall of water levels, expressing the Buffalo Bayou as a shifting, dynamic system. This prototype intends to bring the bayou’s water levels into the public eye, forcing viewers to confront the reality and urgency of sea level rise in their community.

Climate change makes us more vulnerable to heat stress, poor air quality, and certain diseases. However, the effects of the changing environment on our human health are often invisible, and therefore easily forgotten. From Invisible to Visible is a project aimed at making air quality legible in the built environment. Mihalic’s team is currently developing prototypes of an air quality monitoring device that provides real-time air quality information to the public. By making the invisible problem of poor air quality visible to the public, the project aims to build social capacity and raise awareness on climate issues.

Through her work, Mihalic seeks to take the wonder embodied in the weather and translate it into something expressive that brings users into direct conversation with the future. Artists and landscape architects play an important role in building climate literacy and community resilience. Mihalic calls her fellow colleagues to bring the topic of the weather out of the realm of small talk and onto a larger societal platform.

—

This video was filmed on June 26, 2019 in Houston, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium Goes Virtual: Part 2

This year’s annual LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium showcased leading-edge thinking in landscape architecture to address a breadth of pressing issues. During this two-part virtual event, the six 2019-2020 LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership recipients presented their projects as the culmination of their year-long fellowship. The symposium is a celebration of the fellows’ journey to develop their leadership capacity and work on ideas that have the potential to create positive and profound change in the profession, the environment, and humanity.

< RELATED: LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium Goes Virtual: Part 1 >

Established in 2016, the Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership was created to “foster transformational leadership capacity and support innovations to advance the field of landscape architecture”. This $25,000 fellowship is an opportunity for professionals to dedicate the equivalent of 3 months’ time over the course of one year to a proposed project that has the potential to bring positive change and expand the discipline’s impact. The funds provide mid career and senior-level landscape architects the ability to think deeply, reflect, research, explore, create, test, and develop their ideas into action. In addition to the funds, the LAF Fellows receive project support through facilitated discussions, critiques, mentorship, and explorations of transformational leadership that occur during three 3-day residencies in Washington, DC, as well as monthly conference calls.

Like many recent events, the symposium saw a change of format this year and was hosted virtually. This is just one of the ways in which the coronavirus pandemic is expected to impact the landscape architecture profession. While quarantine has illustrated the importance of public space, it has also reminding us that access and treatment within these spaces in unequal. In a joint statement prepared by the 2019-2020 cohort, the Fellows recognize the systemic racism rooted in landscapes, and the progress to be made toward addressing urban inequity, stating: “Watching these events unfold, it became clear that the discourse in landscape architecture must change; that our work has too often been complicit in the marginalization and oppression of black and brown lives. It is up to us to imagine new futures, to dismantle oppressive power structures, and embrace our differences.”

In this moment of crisis, the urgency of the Fellow’s research topics have become even more apparent. As past LAF President Cindy Sanders stated, “Now, of all times, is not the time to stop programs that supports innovation and leadership development. The events of the last few months have only underscored our collective need for transformational leaders who can take us through these difficulties to a more sustainable, equitable, and just world.” This symposium provides a platform to bring important conversations to broader audiences and bring about much-needed societal change.

This online event was broken into two sessions, each day featuring presentations from three of the Fellows. The second session featured fellows Nick Jabs, Associate at PORT Urbanism, Pierre Bélanger, landscape architect and founder of the Landscape Infrastructure Lab, and Hans Baumann, an independent practicing landscape architect.

Nick Jabs – Working Landscapes and the Middle American City

In the design profession, there is lack of critical engagement with Middle American cities. Neither entirely rural or urban, the identity of these “smaller out-of-the-way towns” are often ignored, however their viability is critical and currently in danger. Fellow Nick Jabs set out to explore this often overlooked section of America in an effort to better understand the driving forces that have, and may in the future, shape its physical and cultural landscapes. In his presentation, Working Landscapes and the Middle American City, Jabs explores the past and present condition of Middle American cities through the evolution and intersection of their working landscapes.

Jabs’ research explores the shape of Middle America throughout time, and how the buildings, landscapes, and manufacturing infrastructure have changed along with it. Through a timeline of historical settlements, resource extraction, trade, transportation, and factory production, Jabs outlines the milestones that catalyzed change for the region. He argues that change, either in growth or decline, of post-colonial Middle American cities can consistently be linked back to the extraction and processing of natural resources or manufacturing. As he states, “The dual interwinding projects of capitalism and colonization manifests through manufacturing have shaped and reshaped the physical and perceived identity of Middle America, and especially the form of it is cities.”

Just as manufacturing has shaped and reshaped Middle America, so will our current climate crisis affect the future development of this region. Jabs argues that, due to their history, these communities are uniquely positioned to lead a low-carbon future, stating: “These communities not only have the natural, infrastructural, and physical capacities to make this happen. They have the cultural legacy as well. The very things that have defined the identity of Middle America are the necessary point-of-departure to make this transition.” He envisions a future in which Middle America is the engine for delivering the promises of the Green New Deal, providing decarbonization, justice, and jobs. The Green New Deal policy proposal would provide substantial investment in manufacturing and clean energy systems, places emphasis on bringing environmental, racial, and economic justice to vulnerable communities, and aims to meet 2030 and 2050 carbon goals. If enacted, we could witness a transformation of the region from one predicated on an extractive, destructive paradigm to one that is reciprocal and productive, with an interconnected relationship between the workers, the work being done, and the environment.

The identity and structure of this region has been shaped many times in the past, and it can be shaped again. In a final call-to-action, Jabs pronounces: “It is up to us – through our priorities, our budgets, our activism, and votes – to determine that future.”

Pierre Belanger – Landscape as Foundation for Revolution and Resistance

As landscape architects, we are stewards of the land. But whose lands we are on, and who are we accountable to? When we consider that the land in the U.S. and Canada was obtained through treaties with Indian tribes and acknowledge the history of these reservation lands lost to white development based on broken promises, we come to realize that we are accountable to the histories and legacies of those lands. Fellow Pierre Belanger provided a deeply moving and provocative presentation, Landscape as Foundation for Revolution and Resistance, that considers this question, opening a lens on the past to better understand the extreme climate of oppression and inequalities today. Presented in the form of spoken word, Belanger shares a letter he wrote to the editor of Landscape Architecture Magazine, Brad McKee, critically questioning the professional establishment and academic institution’s unwillingness to address matters of diversity, history, and legacy in landscape architecture.

Belanger proclaims that now is the time for the profession to confront its legacy rooted in dispossession, domination, and exploitation. “Our under-education of white supremacy, the inhumanity of design, and the injustice of the environment, our negligence, ignorance and silence are monumental,” he asserts. In order to clarify who we are as a profession and what our field represents, we must participate in a critical deep dialog and come to terms with histories of slavery and legacies of racism in the U.S. Landscape architects must decide if they want to champion change by engaging in deep dialogues about spatial injustice and racial erasure to rise up against legacies of white supremacy and dismantle settler colonialism. To work closer to the communities that we are accountable to, Belanger started a non-profit organization, OPEN SYSTEMS, and, with his co-founders, drafted a 38-point Deign Manifesto, continuing his mission to reclaim landscape, land, and life.

Hans Baumann – Immaterial Outcomes: Tribal Sovereignty and Design Collaboration at the Salton Sea

How would our understanding of the land change if landscape architects engaged more regularly with tribal communities? Tribal communities represent an incredibly diverse resource for understanding the places that we live and work, and yet we as design professionals do not acknowledge their expertise. Several of the 2019-2020 Fellows chose to research topics related to marginalized communities and tribal lands. However, Fellow Hans Baumann is the only to have immersed himself in a long-term collaboration with tribal members. In his presentation, Immaterial Outcomes: Tribal Sovereignty and Design Collaboration at the Salton Sea, Baumman reflects on his collaboration with the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians of Southern California, sharing how landscape can act as a medium between design methodology and Indigenous knowledge. His work illustrates why landscape architects must engage with North America’s diverse tribal peoples, especially during the current era of unprecedented ecological change.

The tribal lands of the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians surround the Salton Sea, the largest body of water in the state of California. Once a freshwater lake seen as a place of livelihood, the water quality has declined in recent years largely due to agricultural dumping, and the result is a shrinking, increasingly saline waterbody. Efforts are being made to better protect the quality of this important water resource, and Torres-Martinez is eager to take an active role in restoration efforts. As the largest private landowner in and around the Salton Sea in the lower Coachella Valley, the tribal community has a cultural connection to this unique ecosystem, however Baumman discovered that only 2.3% of maps in “Salton Sea Atlas” make reference to the Cahuilla peoples, tribal land holdings, or tribal reservations – effectively erasing the community’s ties to the region.

While this is very much an ecological issue, it is much more personal for the tribal community. And, while the tribe’s connection has been largely ignored to-date, their long-standing relationship to the land offers an important perspective. Baumann suggests that these cultural and ecological issues are interdependent and is working to bring the cultural perceptions to the maps and representational frameworks. In the Fall of 2017, Baumann met with the community’s tribal government, suggesting an inclusive approach to the Salton Sea crisis – one that emphasizes the community’s personal and cultural connections to the water. A partnership has since been formed, developed through a series of community workshops led by artists and culture bearers in the tribe and supported through a youth apprenticeship. Baumann’s role is to support the development of ideas in the community workshops and to facilitate continuity over the life of the project.

As an outsider, Baumann has learned much about the process of working with tribal communities, emphasizing that this work should not follow a linear process. Relationship building and trust is critical, and factors such as deadlines can turn relationships into transactions. Through this partnership, Baumann has concluded that we must dismantle the thinking and assumptions that exist in the field of landscape architecture that has historically isolated us from these tribal allies. We must reframe our role and understand that we are entering a long term process of listening and consensus-building. In conclusion, he states: “This is not a call for us to lead the way. What it is is a call for us to step aside; to make space; and to find the interest and capacity to support the work being done by tribal governments and tribal peoples now, in the present.“

—

Presentations from Part 2 of the 2020 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium can be viewed on the LAF website. Those seeking continuing education credits can earn 1.0 PDH (LA CES/HSW) following successful completion of a short quiz.

LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium Goes Virtual: Part 1

This year’s annual LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium showcased leading-edge thinking in landscape architecture to address a breadth of pressing issues. During this two-part virtual event, the six 2019-2020 LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership recipients presented their projects as the culmination of their year-long fellowship. The symposium is a celebration of the fellows’ journey to develop their leadership capacity and work on ideas that have the potential to create positive and profound change in the profession, the environment, and humanity.

< RELATED: LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium Goes Virtual: Part 2 >

Established in 2016, the Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership was created to “foster transformational leadership capacity and support innovations to advance the field of landscape architecture”. This $25,000 fellowship is an opportunity for professionals to dedicate the equivalent of 3 months’ time over the course of one year to a proposed project that has the potential to bring positive change and expand the discipline’s impact. The funds provide mid-career and senior-level landscape architects the ability to think deeply, reflect, research, explore, create, test, and develop their ideas into action. In addition to the funds, the LAF Fellows receive project support through facilitated discussions, critiques, mentorship, and explorations of transformational leadership that occur during three 3-day residencies in Washington, DC, as well as monthly conference calls.

Like many recent events, the symposium saw a change of format this year and was hosted virtually. This is just one of the ways in which the coronavirus pandemic is expected to impact the landscape architecture profession. While quarantine has illustrated the importance of public space, it has also reminding us that access and treatment within these spaces in unequal. In a joint statement prepared by the 2019-2020 cohort, the Fellows recognize the systemic racism rooted in landscapes, and the progress to be made toward addressing urban inequity, stating: “Watching these events unfold, it became clear that the discourse in landscape architecture must change; that our work has too often been complicit in the marginalization and oppression of black and brown lives. It is up to us to imagine new futures, to dismantle oppressive power structures, and embrace our differences.”

In this moment of crisis, the urgency of the Fellow’s research topics have become even more apparent. As past LAF President Cindy Sanders stated, “Now, of all times, is not the time to stop programs that supports innovation and leadership development. The events of the last few months have only underscored our collective need for transformational leaders who can take us through these difficulties to a more sustainable, equitable, and just world.” This symposium provides a platform to bring important conversations to broader audiences and bring about much-needed societal change.

This online event was broken into two sessions, each day featuring presentations from three of the Fellows. The first session featured fellows Jeffrey Hou, Professor of Landscape Architecture and Director of Urban Commons Lab at University of Washington, Liz Camuti, Landscape Designer at SCAPE, and Diana Fernandez, Associate at Sasaki.

Jeff Hou – Design as Activism: Educating for Social Change

Facing environmental and social crises on a global scale, how can landscape architecture education prepare students to become changemakers in meeting these challenges? Fellow Jeff Hou sought to answer this question in his presentation Design as Activism: Educating for Social Change, in which he presented a framework of actions to reposition and transform landscape architecture education for social change. Using design as a vehicle for change, the profession of landscape architecture has the capacity to make a more meaningful contribution to society in terms of equity, justice, and resilience. To grow our collective capacity and build future leaders, Hou suggests we need to better integrate design activism into the educational curriculum.

In his research, Hou explored the different expressions of design activism, the skills and knowledge needed for practicing it, and the actions needed to integrate it into curriculum. Working alongside his students at University of Washington and receiving input from a network of university program leaders and practitioners across the county, Hou created a 50-page document titled “Design As Activism: A Framework for Actions in Landscape Architecture Education”. The document outlines a series of principles to guide actions that programs can take to integrate design activism into their curriculum. As Hou states, “Each of these actions represent an opportunity to transform the way we teach and the way we learn, to expand the skills and knowledge of our future professionals, and to recognize the power of design in bringing about change.” Calling on us all to make this transformation happen, Hou plans to distribute the documents to universities around the country and seek endorsements from leaders.

Liz Camuti – Un-Checking the Boxes: Learning to Read Between the Lines of Climate Resilience RFPs

Although socially and economically marginalized communities are the first to be affected by climate change, their voices are often some of the first to be ignored. Fellow Liz Camuti invites us to think differently about resiliency planning and our capacity as landscape architects to give voice to vulnerable communities. Using the resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles – a sliver of island 80 miles southwest of New Orleans – as a case study, Camuti’s work, titled Un-Checking the Boxes: Learning to Read Between the Lines of Climate Resilience RFPs, questions: 1) how criteria for a “successful” project might evolve through a different form of RFP, and 2) how designers can adapt their roles to break cycles of erasure and control that have shaped environmental history in Louisiana.

The residents of the Isle de Jean Charles are Louisiana’s first climate refugees. The historic homeland to the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe, this primarily American Indian community has lost 98% of its land due to rising sea levels, saltwater intrusion, and subsidence in just two generations. In 2002, seeing the need to relocate this community to safer ground inland, the US Amy Corps of Engineers identified a new site where the community could rebuild and began planning for resettlement. But the majority of residents and tribal leaders from Isle de Jean Charles did not want to relocate due to their culture’s close ties to the land. Despite the extensive design and planning process, many residents feel that the new plans do not reflect the goals and objectives that the community had for themselves. While many hoped this resettlement would provide a blueprint for the future as rising seas are projected to advance upon more low-lying communities, it is clear that the project did not understand the true cost of relocation.

In her research, Camuti delved into this project’s Request for Proposal (RFP) document and the resultant design process to understand why a well-intended design solution failed to meet community needs. Unfortunately, parameters set forth in RFP documents are often not reflective of the structures and traditions of the communities said projects seek to assist. Engagement is often limited to reducing conflict instead of investing in authentic collaboration, leaning into tensions, and wholeheartedly seeking community support. Camuti proposes a re-thinking of how landscape architects review and respond to RFPs, re-evaluating how RFPs define client, cost, scale and time, public participation, and cultural history. She asserts that we need to go beyond “checking the boxes” to address the true challenges unique to each community. As Camuti states, “We have the capacity to develop more creative ways of reading between the lines of RFPs in order to truly serve communities.”

Diana Fernandez – Heterogeneous Futures: Design-Thinking Alternatives for Anthropologically and Ecologically Diverse Landscapes

By definition, public space belongs to the people – to all of them. But how people experience space is very different depending on their identity and public spaces often fall short from meeting the goal of welcoming people of every age, gender, race, income, or sexual orientation. As Fellow Diana Fernandez explains in her presentation, public space has historically been built by a hegemonic discourse, excluding the lived experiences of marginalized communities. As landscape architects, Fernandez believes we need to increase the pathways for these voices to be heard. In her research, titled Heterogeneous Futures: Design-Thinking Alternatives for Anthropologically and Ecologically Diverse Landscapes, Fernandez seeks to ensure public landscapes reflect the multiculturalism of the people that inhabit them.

In the U.S., the shaping of public spaces has been historically determined by institutionalized requirements and power structures, prioritizing Euro-centric principles of design and intentionally restricting “undesirable” populations, such as the homeless or skateboarders. These practices have continued to plague and perpetuate injustice and inequality in the public realm. Fernandez’ research builds on the current movement of landscape architecture toward incorporating social, cultural, and linguistic knowledge as critical aspects of the design process. By focusing on community-defined design excellence and allowing the community to define beauty, we can create spaces that are more resilient and representative of communities of all backgrounds.

Heterogeneity is a term often used to describe the resilience of ecological or biological systems. The diverse qualities of heterogeneous landscapes enable them to thrive when exposed to outside forces, such as natural disasters, environmental change, and pandemics. Asserting that we need embrace heterogeneity as a landscape process, Fernandez identifies key indicators for designers to practice in the design process. By adjusting our state of consciousness, we can make space for learning, unlearning, healing, and acceptance of differences in public space. For more information about her research, visit Fernandez’ website, Heterogeneous Futures.

_____

Presentations from Part 1 of the 2020 LAF Innovation + Leadership Symposium can be viewed on the LAF website. Those seeking continuing education credits can earn 1.0 PDH (LA CES/HSW) following successful completion of a short quiz.

The Aesthetic of Proof [Video]

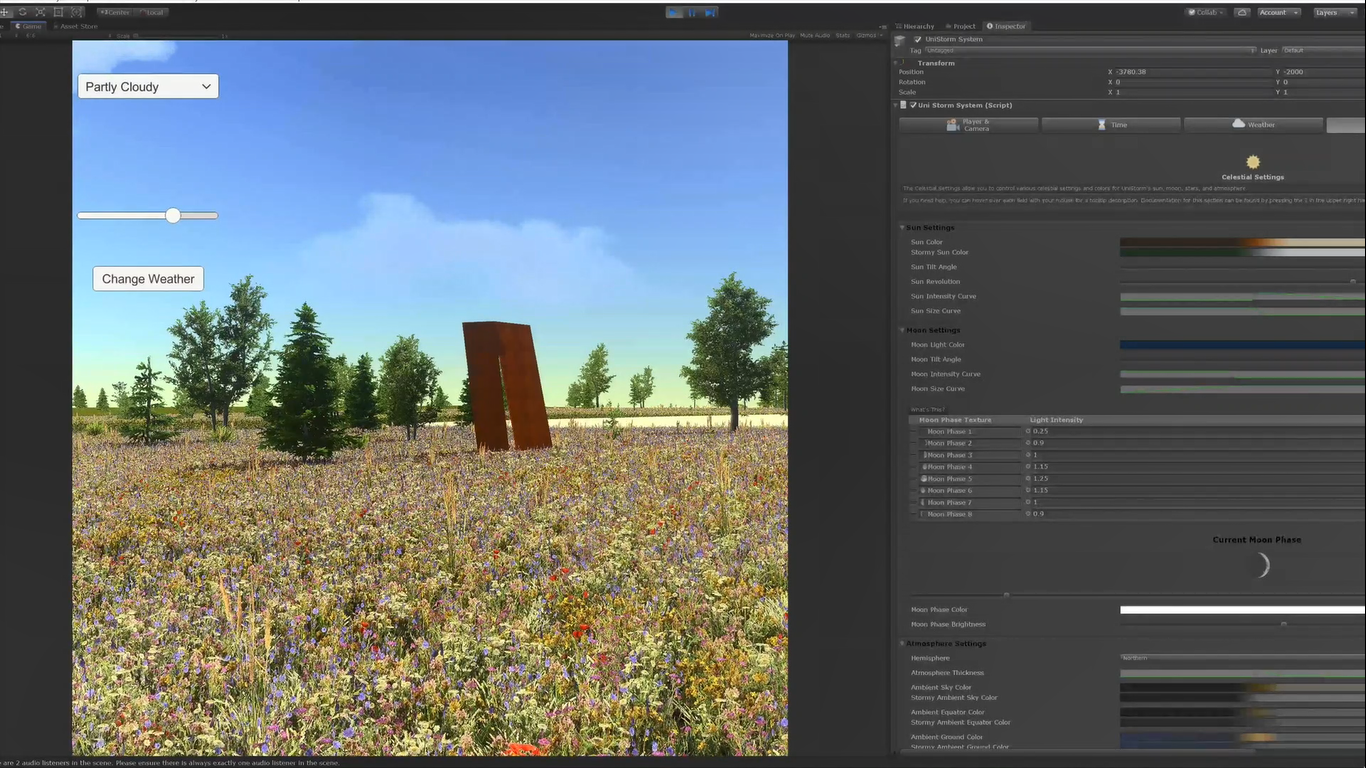

As designers, we are constantly seeking new tools and strategies to better express our design vision. Technological advances have enhanced our visualization capabilities dramatically over the years, from hand-drawn perspectives to photo-realistic renderings and 3D digital models. Yet, much of what makes a landscape unique – the feelings, smells, and sounds of the natural environment – are not being communicated in our graphics. Andrew Sargeant, landscape designer and visualization specialist for Lionheart Places LLC, believes that augmented reality and virtual reality (VR) provide greater potential than all previous rendered visualizations of landscapes. During his presentation at the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Austin, TX, Sargeant shared why he believes immersive technology is the future of landscape representation.

A pioneer of design technology in the field of landscape architecture, Sargeant is keenly interested in developing innovative ways to visualize the design work of landscape architects. From site analysis to design iteration to client communication, immersive technology has a lot to offer the discipline. Currently, the sensory factors we experience in landscapes – sounds, scents, and the feeling of warmth or wind – are missing from our visual representations. Our graphics do not effectively show all of the potential experiences and temporal qualities of designed landscapes, often misrepresenting the key characteristics that make a space special or unique. Immersive technologies provide a more realistic experience, allowing users to more fully interact with a design and experience the changing seasons. As Sargeant states: “A picture is worth a thousand words, but an experience is worth much more.” With VR and augmented reality, designers are able to provide clients and community stakeholders with interactive experiences of designed landscapes.

The Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) recognized the potential this technology has to advance the profession by selecting Sargeant as recipient of the 2018-2019 LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership. This yearlong program is intended to develop ideas that have the potential to create positive and profound change in the profession, environment, and humanity. During his fellowship, Sargeant endeavored to discover the latest visualization tools and explore the possibilities immersive technology can provide to the profession.

Disillusioned by the “sunny day” renderings, which do not show the lived experiences and experiential qualities of the landscape, Sargeant began exploring how to use VR to bring landscape representations to life. Utilizing video game design engine Unity, Saergent explored the capabilities of this software to gain a better understanding of the challenges, considerations, and successes of immersive technology. While the software has a steep learning curve, he was able to successfully integrate this tool into his practice. During his presentation, Sargeant shared an example of a project east of Austin adjacent to the Colorado River, susceptible to rising flood waters. Because of the site’s unique location, the design solution needed to address rising tides and accommodate change. Sargeant utilized immersive technology to depict the site during a 100-year storm surge, complete with the visual and auditory stimulants of heavy rain and booming thunder. By demonstrating the experiential qualities of the site, Sargeant was able to show how immersive technologies foster a sense of authentic human experience.

Sargeant believes the adoption of immersive technology will give landscape architects a competitive edge, and inspire new ways to think and design. To encourage the spread of immersive technology, Sargeant is actively working to successfully integrate immersive technology within professional practice and academia. He hopes that these solutions can be made available for all to use in the design of and advocacy for public space.

Follow Andrew Sargeant on Twitter and Instagram @bydesigndrew

—

This video was filmed on June 25, 2019 in Austin, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Plant Stuffing [Video]

From urban farming to forest bathing, there has been a growing desire to connect with the natural world. In an effort to bring nature to urban settings, some landscape architects are turning away from conventional horticultural practices, where plants are organized in orderly rows and treated as separate, distinct clumps, in favor of a freer aesthetic that reflects the wildness of nature and is attuned to ecology. During her presentation at the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Austin, TX, Jennifer Orr, a founding principal of Studio Balcones, discussed the importance of designing “wild” landscapes in the public realm to help restore ecological diversity in urban settings. Orr advocates for crafting landscapes that work with nature instead of trying to control it. This plant-driven approach for public landscapes aims to reconnect people with larger natural systems.

To achieve the performance goals of today, plants must do a whole lot more than just be ornamental. They must provide wildlife habitat and food, filter stormwater runoff, support biodiversity, enrich soils, cleanse air, reduce the heat island effect, and improve mental health WHILE making spaces more beautiful. Achieving these broader ecological goals requires an understanding of how plants fit together. Naturalistic design takes cues from nature, organizing plants the way nature does, in richly layered, diverse communities. Plants are fit together in ecological combinations and arranged in an intermingled style, bleeding into each other. This plant-rich design approach yields multi-purpose, beautiful landscapes that support biodiversity.

Orr is not the only landscape architect calling for a revolution in planting design. The naturalistic movement originated in the Netherlands over 30 years ago, with famous garden designer Piet Oudolf at the forefront of the movement. More recently, projects like the High Line in New York City and Chicago’s Laurie Garden (both designed in collaboration with Piet Oudolf) have brought this type of planting aesthetic to urban environments, launching the public awareness and popularity of naturalistic planting design. Intended to be ever-changing, dynamic, and emotion-laden landscapes, these places make us reconsider the role of landscapes in public spaces.

As described by Tony Spencer in an article on his blog, The New Perennialist, naturalistic plantings are composed of a series of interwoven plant layers together forming a community, abstracting the patterns and relationships found in nature. He writes: “Particular attention is paid to how each plant grows from the roots on down—whether it clumps or runs, and how well it responds to stress and competition. Every detail of a given plant’s habit provides a clue into how well it plays with others and what ecological niches it can fill”.

Image: Studio Balcones

Mastering this art requires a deep horticultural knowledge and an understanding of the intricate relationships between plants. Fortunately, as popularity grows, so too have resources and publications to master this design aesthetic, including Nigel Dunnett’s Naturalistic Planting Design: The Essential Guide (2019), Claudia West and Thomas Rainer’s book Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes (2016), and Wild by Design: Strategies for Creating Life-Enhancing Landscapes (2016) by Margie Ruddick.

So, how can we actualize the power of plants to more effectively drive ecological function in our towns and cities? In urban environments, where space is at a premium, Orr suggests “plant stuffing”, or planting as many plants in as many spaces as possible, to underscore the importance of plant layering and variety.

This type of “wild” planting design is often perceived as messy or formless, leading to concerns over maintenance. Orr asserts that we should embrace the messiness of nature, while also understanding that there is a right balance to strike in naturalistic planting design. Designs should interpret nature, but also be legible. To achieve this balance, selecting the right plants – plants that are adapted to the soil and climate of a specific site – is key. If done correctly, this planting approach actually requires less labor over time, avoiding the typical maintenance burdens of watering, mulching, spraying, and pruning.

Orr encourages designers to experiment with the naturalistic planting style, see what examples of best practices are out there, and discover the beauty of gardening in a naturalistic style. By harnessing the power of plants, we as landscape architects are able to create resilient, memorable, and vibrant landscapes.

—

This video was filmed on June 25, 2019 in Austin, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Altering Human Habits [Video]

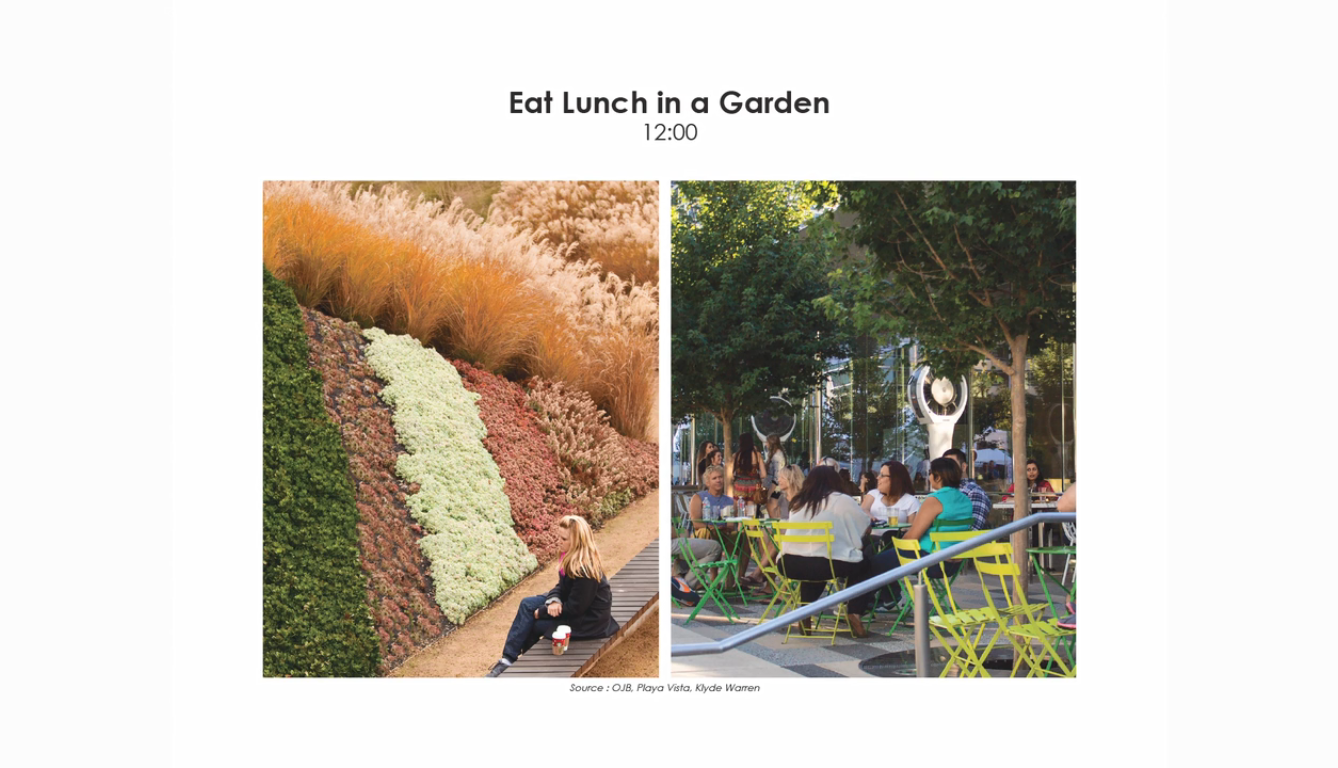

Spending time outside not only makes us feel healthier, it also impacts our long-term wellbeing. Studies have shown that people with high exposure to green spaces yield significant physical and mental health benefits. Yet, most of us do not prioritize outdoor activity in our daily lives. According to the EPA, the average American spends 93% of their time indoors, leaving very little time for outdoor activity each day. To promote human wellbeing, we need to alter our daily routine to accommodate outdoor activity. In her presentation at the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Houston, TX, Cynthia Dehlavi, Senior Research and Design Associate at OJB Landscape Architecture, shared how landscape architects can use design to influence human habits and increase people’s daily exposure to green space.

During her presentation, Dehlavi walked participants through a meditative experience to demonstrate the effects that our surroundings can have on our bodies. Research has shown that an indoor, sedentary lifestyle impacts your mood, causes fatigue, disrupts your sleep cycle, and even increases your chance of catching an infection. This has a tremendous effect on our bodies including eye strain from staring at a screen, back pain from a hunched seating posture, and lung disease from poor air quality. Conversely, spending time outdoors provides measurable health benefits, including reducing stress and anxiety, improving concentration, and strengthening your immunity. Dehlavi recognized that landscapes can fulfill many of our bodies’ needs. Motivated by a desire to help others receive the restorative health benefits nature provides, Dehlavi began to consider how she as a landscape architect can use design to influence individuals to make positive changes to their daily routine and pursue a healthier lifestyle. Here are a few ways Dahlavi and her team at OJB are using design to shift human behavior and promote wellbeing:

Bike or Walk to Work

More than 85% of workers drive to the office every day. For many of us, this daily commute feels like a chore, but it could be an untapped opportunity to fit outdoor time into your day. Changing your mode of transportation from vehicle to foot or bicycle can reap huge health benefits. Not only is your physical health improved, studies have also shown evidence that productivity and positivity are increased when people change their behavior to active commuting. To promote an active commute, landscape architects are working with cities and towns to implement more pedestrian and cyclist friendly practices, such as dedicated paths or protected bike lanes and bicycle rentals.

Take Breaks

Since the average person spends 12+ hours a day sitting – i.e. at their desk, behind the wheel, or in front of the TV screen – taking breaks is essential. However, one study has shown that only one in three workers actually step away from their desk to take lunch. While skipping your lunch break may seem beneficial to completing a deadline, it actually reduces your productivity and deteriorates your mental state. Without taking adequate breaks, overall work performance begins to suffer. While finding time for a break can be challenging, it has shown to increase productivity, improve mental well-being, boost creativity, and encourage healthy habits such as a healthy lunch, exercise, or meditation. To encourage movement throughout the day, landscape architects are teaming with office building developers to provide both active and passive outdoor amenity spaces including walking trails, picnic benches, and gardens.

Take It Outside

While the benefits of being outside are well-established, 65% of employees say that their work is the reason that they don’t get outside as much as they would like. Studies have shown that employees with a view of nature perceive lower levels of job stress and higher levels of job satisfaction. To capitalize on these benefits, employers are starting to integrate the outdoors into the workday. Companies are re-imagining their office space to bring the outdoors in, opting for natural light, fresh air, and indoor plants or natural building materials. In addition, with remote work technologies, it’s easier than ever to take your work outside or hold outdoor meetings. Landscape architects are working with clients to provide outdoor workstations.

While Dehlavi is motivated by the desire to improve wellbeing, she also acknowledges that encouraging an increase in people’s daily outdoor activity will also benefit the profession of landscape architecture. She states: “If we change the culture from only being outside 7% of the day to 20% or more, then there is more demand for high-quality landscapes.” By altering people’s daily routine, we can increase the need and demand for better outdoor living, working, and relaxing spaces. Dehlavi encourages landscape architects to be better advocates of human wellbeing, designing spaces that allow for a shift in human behavior and increase daily exposure to green space.

—

This video was filmed on June 26, 2019 in Houston, TX as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

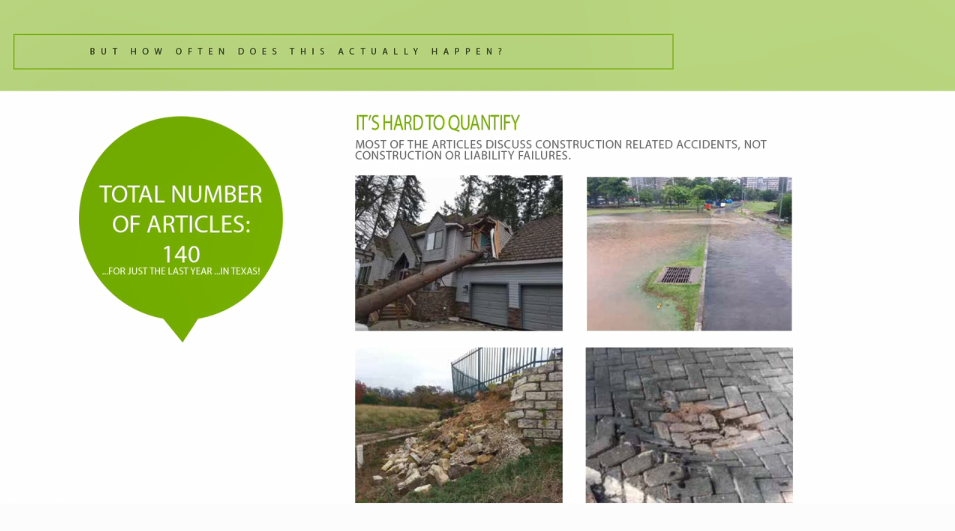

Managing Risk [Video]

The work of landscape architects work involves complex decisions and responsibilities — detailing and designing projects, observing construction, achieving owner satisfaction, and ensuring the health, safety, and welfare of the public. Landscape architects are subject to professional liability as a direct result of the higher expectations placed on us due to our specialized education and training. When a project doesn’t go according to plan, owners can file lawsuits against the design firm. Risk are inherent in the landscape architecture profession, but we rarely talk about it. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Austin, TX, Marissa McKinney, Principal at Austin-based landscape architecture firm Coleman & Associates, discussed the many ways in which design professionals expose themselves to legal liability and how design firms can mitigate risk.

Analyze Risk

Risk management should begin before a contract is even signed. To reduce unforeseen problems, it is important to identify potential risks early on, and analyze the risk’s potential impact and its likelihood of occurring. Before taking on a new project type or working with a new client, as yourself “is it worth the risk?”. By planning a risk response and implementing it, you avoid, minimize, and/or accept the risk.

Set Owner Expectations

Professional liability claims are often a result of a failure to manage expectations. A well-written contract is the first step to reduce liability, and is the best way to set both parties’ expectations on a project. It sets a clear understanding between the client and designer of the landscape architect’s scope of work, and the quality and timing of the final product. A contract allows both parties to clearly document their mutual understanding for project requirements and obligations, which should reduce the likelihood of a later dispute. Poorly written contracts and ambiguous language can expose firms to unintended risks. While standard contract forms, such as those provided by ASLA, are a useful first step, getting legal review of standard contracts is another important assurance.

Communication is Key

When unexpected schedule delays or cost overruns occur, communication to the client is key. Lack of communication may result in a big – and often costly – surprise later for the client. Make sure that the contract details all the terms of your work – including deliverables, deadlines, and pay rates – so both parties have everything in writing. If a project’s scope changes or you take on more responsibilities, it’s a good idea to modify and re-sign the contract so that these changes are spelled out and can be covered should something go awry. Regularly check in with the client throughout the project so that you can manage expectations and stay aware of new or shifting priorities. Be proactive by taking and distributing comprehensive meeting notes and getting direction in writing to prevent disputes later on.

Practice Standard of Care

Although landscape architects strive for perfection in their work, errors happen. Most mistakes are caused by the complexity of the design coupled with human limitations – i.e. a code requirement might be over-looked or dimension miscalculated. By using the standard of care clause, professionals can protect themselves from liability if the issue of negligence should arise. Under this standard, the design professional is held to use the same degree of care as is ordinarily practices by other reasonably competent landscape architects. The standard of care sets realistic expectations; however, it is typically the responsibility of the landscape architect to perform quality control of their drawings, ensure drawings are properly coordinated between consultants, and review bidding documents for compliance with client instructions, regulatory code, and other requirements. However, landscape architects routinely do not guarantee construction outcomes because they are not capable of making those guarantees come true.

Reduce Responsibility

Much of the risk occurs during construction. A landscape architect’s approach to construction administration can greatly affect risk exposure and its outcomes. Contractors are your first line of dense in flagging potential errors. Encourage them to ask about suspected errors and omissions and respond quickly to their requests to set a pace for a constructive dialogue in the future. The landscape architect should also conduct site visits to ensure construction quality. Should potentially costly decisions need to be made, reduce liability by allowing the client to make those hard decisions. Unfortunately, the design firm is not always contracted to perform construction observation services, or an exhausted fee limits their ability to control liabilities. For this reason, clear expectations and an understanding of responsibility are again vital.

Depending on the contract language, the landscape architecture practice can be held liable for the negligence of contractors or sub-consultants working on a project. Even if you’ve detailed and specified suitable materials, there is no guarantee that the construction project manager will follow your instructions or that you will be made aware of substitutions. If there are flaws in the finished product due to construction mistakes, the owner could sue the landscape architect for negligence and hold them liable for damages. Similarly, McKinney shares an example of a practitioner who included the structural engineer’s mark-ups of a retaining wall within their landscape architecture drawings. When the wall failed, the client held the landscape architect responsible despite the mistake being caused by the sub-consultant. It is important that you avoid accepting responsibility for other people’s negligent acts. One way to do so is through the use of an indemnity clause. Indemnity is an agreement to assume a specific liability in the event of a loss, shifting risk from one party to another.

Emerging / Specialized Risks

Today, landscape architecture projects are expected to mitigate climate change and respond to a host of constantly evolving future variables. As projects become more complicated and require specialized expertise to achieve desired environmental outcomes, the risk landscape architects face is heightened. Similarly, complicated projects require more customized details and increase liability. Practitioners should expect proper compensation for taking on such risks, while also protecting themselves from undue liability by ensuring they are up-to-date on latest practices, curating a sub-consultant team of knowledgeable experts, and managing client expectations.

Liability Insurance