Gentrification is a term that emerged in the mid-1960s to explain the demographic and social changes that some neighborhoods in the London were experiencing. Since then, a vast number of articles and essays on urban transformation have sought to explain this phenomenon.

In this article, we shall explore how to detect areas that are likely to be affected by this process, how to identify those that are already being affected and how to prevent this from happening to preserve heterogeneity, social inclusion, and sustainability in our cities.

But what exactly is gentrification?

The word gentrification coming from the English syllable “gentry”, refers to the British rural nobility. Gentrification was originally coined to describe the emergence of middle-to-higher-income social groups in neighborhoods that led to the displacement of the working classes that originally inhabited these areas. This resulted in a loss of local identity and fragmentation of the community. However, gentrification is no longer restricted to urban centers or first-world metropolises. As Jason Hackworth and Neil Smith wrote in their essay titled ‘The Changing State of Gentrification’: “Gentrification is the leading edge of the urbanization of human evolution‘.

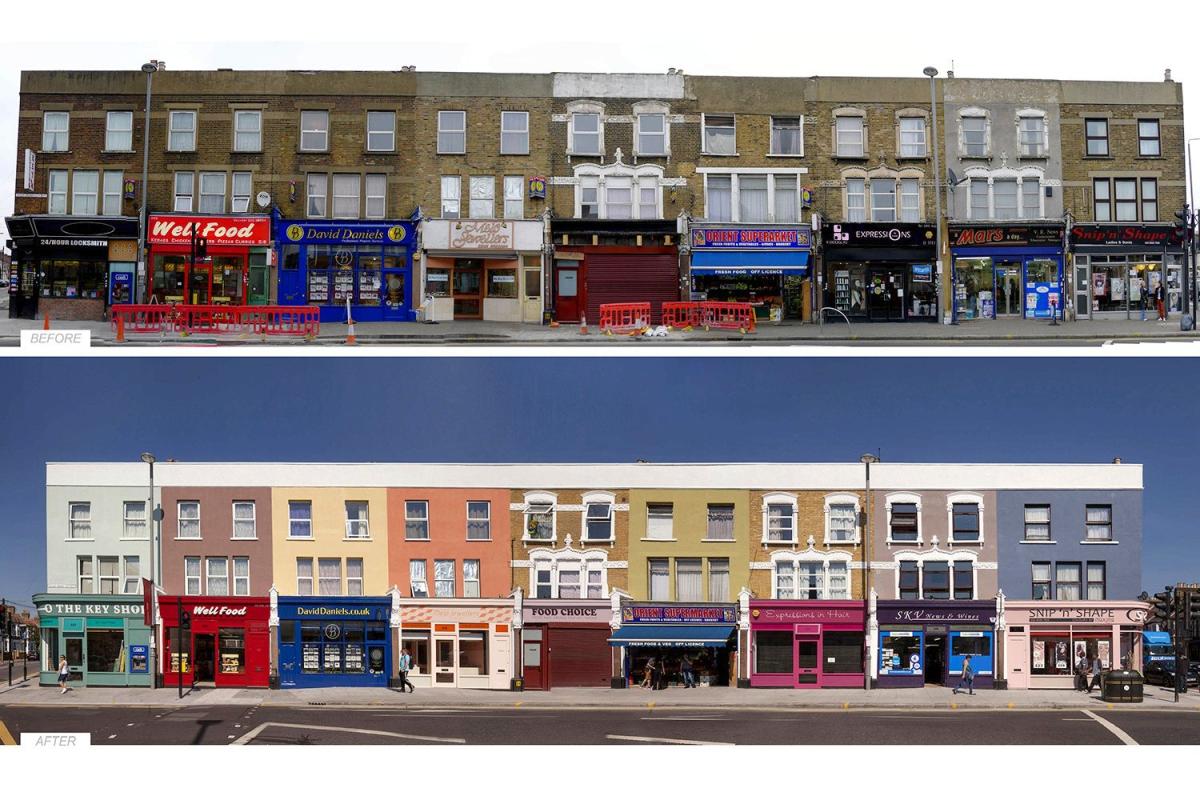

Leyton High Road, in Waltham Forest, London. was given a makeover before the 2012 London Olympics.

The globalization of gentrification.

The Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman coined with the term “Liquid Modernity” which refers to a phenomenon that leads to the creation of egalitarian consumption patterns, a loss of cultural diversity, and an uprooting of identity. In this paradigm of a lack of personal commitment to long-term local goals, there is a contradiction between the search for freedom, the desire for change and the fear of not knowing what will happen.

The ephemerality of current values that were highlighted the global economic crisis in 2007 and the ongoing environmental and migration crisis can be understood to be a particularly western perspective problem. Historic values and traditions are undermined, generating a false identity that temporarily binds these communities but is built on weak foundations, causing uprooting of populations.

Carnaby Street, London, 1982 and present day

As we can see in this image, the traditional local shops in London’s Carnaby Street have been replaced by international corporate companies resulting in a neighborhood that lacks a strong local identity and affordability.

Fortunately, the notion of ‘use and throw away’ that consumerism has given us is changing into new movements. A responsible action considering the global trend towards urbanization and the effects of climate change with proposals such as promoting the circular economy can add value and improve the sustainability of the neighborhood. Thus, globalization is one key precipitator of gentrification.

Tips for identifying areas susceptible to gentrification.

- Dwellings are usually small, and the rent prices are low.

- The profile of the inhabitants is low income, usually without higher education.

- Urban decay. Existence of a general degradation of the neighborhood and it’s infrastructure.

- Proximity to other areas with higher rental values.

Although each area has its unique circumstances, these broad factors can mark the potential for financial speculation that drives property prices, pushing out existing populations through increases in rent, inflated offers for their properties, or as a result of the rise of the cost of living. This marks a phase of expulsion, investment, and marketing.

Protest against gentrification and displacement on trail 606 in Chicago in 2016. Photo by Tyler Lariviere.

The demand for more green spaces by the inhabitants of Chicago sparked the idea of reusing an abandoned railroad line as a linear park. The 606 (named after the Chicago ZIP Code prefix), was opened in 2015, with community support and consultation forming part of the design process. They wanted a path for people who lived there. Given the recent economic crisis, no one expected home prices to rise. However, the investment in the area leads to increased interest from investors and higher earners, leading to a degree of gentrification. But important lessons were learned, and steps have been taken to mitigate this, including a recent push for affordable housing in the area. The experience gained is being applied to other parks projects in Chicago.

Tips for detecting gentrification as an ongoing process.

- Galleries and small arts and crafts shops appear. Artists are often the first to arrive attracted by historic architecture and low prices.

- Plans to improve public transport and connectivity.

- Real estate demand increases sharply.

- The number of international retail outlets increases.

- Gradually, the social shape of the neighborhood changes to a demographic of higher earners.

- Investment of green areas, public spaces, and road lighting.

- Crime rates fall.

- Tourism increases. Entire buildings are converted into holiday rental apartments.

The 606 Trail by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates.

Tips for avoiding gentrification.

It is important to be aware and consider the responsibility that comes with urban intervention and its social impact. Every urban planning project must involve the local community and contemplate the area in relation to its context, seeking a socio-economic balance in a sensible and measured way and never as economic policy.

Practical steps that can be undertaken to minimize gentrification:

- Detect the situation in time. What’s going on? Who needs to be involved? Which is the most vulnerable population? Talk to neighbors and stakeholders.

- Turn problems into goals. Establish a list of neighborhood issues and possible solutions in conjunction with the local community.

- Develop an action plan. Consider the resources available. Involve the community and consider their skills. Integrate these into existing policies, plans, and programs.

- Measure the results of these interventions including quality of life.

The Mission neighborhood in San Francisco has always been a neighborhood of immigrants and minorities. In the 1980s it became a hub for the LGBTQ+ community, being a marginal but inclusive area. Now, because of a range of factors including, a rise in population and the attractive (and relatively affordable) Victorian houses in the neighborhood, there has been an expulsion of current residents due to the increasing rental prices.

Street mural on the mission district in San Francisco

However, residents are still struggling with art, community, and activism to preserve the cultural environment of the minorities who reside there, seeking social justice, and resisting the financial interests north of Market Street. They have been able to take advantage of their problems with activities such as the creation of tours where local artists explain the history of the neighborhood in murals. The quality of the streets has improved, and citizen security is ensured by social control.

It is important to keep in mind that it is not about looking to blame social groups that move in because of their economic advantage or deride artists who open shops attracted by low rents. What is troubling is the distribution of land ownership, land speculation, and the vulnerability of the population exploited in favor of financial gains. The rest are consequences. As designers, we are committed to creating spaces that solve the needs of their end-users, with the greatest possible satisfaction and the best possible user experience.

Can landscape architecture and urban design solve the problems of gentrification

Careful planning of green spaces in consultation with the community, for example, can avoid a pocket park from becoming an attractor for gentrification, while adding positive effects to the health and well-being of the existing local residents.

While urban design and landscape architecture may not be able to entirely solve the problem of gentrification, as designers of cities, we can make sure that our projects do not compound the issues of disenfranchisement of minority and vulnerable communities, loss of local identity, and increased land speculation that can lead to gentrification.

—

Article by Ana Muñoz

Lead image by Jack William Heckey

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured