Working together with more experienced designers on site is a one of the most effective ways for new designers to build knowledge quickly.

Landscape architects are expected to know a lot about a lot. Ecology, social dynamics, construction detailing, CAD/Adobe/BIM? That’s just a one-hand list we all spin through in a few years at design school. However, once we emerge into practice – the expectations are still there, but the knowledge-building gets more haphazard.

In practice? Carol knows how bidding processes work and who to call at each department of the city to get permits moving. Imani can estimate slope percentages without pulling out a tape measure. Chris is the plant person. You’ve all seen it.

Individual designers having specialist expertise is great – but too much fragmentation in a design organization’s knowledge base creates problems for individual designers, projects, and businesses.

Lack of clear knowledge management practices creates intergenerational frustration. Experienced designers complain about younger designers not knowing how to do things. If there’s no clear path to building skills and positioning yourself for advancement, young designers aren’t empowered to mature and grow as professionals. Failure to share all of the necessary information results in wasted design time and unnecessary revisions. Knowledge silos make businesses highly vulnerable to staff turnover.

How might a landscape architecture studio build their knowledge assets intentionally? Looking for a structure of how to approach this topic, I asked ChatGPT to define knowledge management:

“Knowledge management refers to the process of capturing, organizing, storing, sharing, and applying an organization’s collective knowledge and information to achieve its goals and objectives. It involves the systematic management of both explicit knowledge (information that can be documented, stored, and shared) and tacit knowledge (intangible insights, experiences, and expertise held by individuals)”

What would it look like for a landscape architecture practice to fulfill these five components of a knowledge management process? Let’s go:

CAPTURING

EXPLICIT KNOWLEDGE

Design professionals are accustomed to capturing explicit knowledge. Especially when it comes to project-related information, we’ve got this down. Gather base information. Research the history of the site. Document site conditions with photos and videos. Take clear notes with deliverables and responsibilities during client meetings. You’ve got this one.

IMPLICIT KNOWLEDGE

When it comes to implicit knowledge, most designers’ glasses fog up. We all respect the seasoned professional who just seems to know what to do regardless of the situation. How do you transmit this breadth of experience in an effective way?

One practice for transmittal of implicit knowledge is to schedule regular Learning-In-Action sessions involving more- and less-experienced designers. I’ll go into this in detail in the “sharing” section at the end of the article.

You can also turn implicit knowledge into explicit knowledge by creating templates, workflows, and checklists. Figure out the steps that an experienced designer goes through in considering common design situations. Perhaps it’s configuring a site plan for a specific parcel and pro forma. What information does that designer gather? What steps do they take to get to a final result? Forcing your experienced designers to be explicit about what they’re considering – and attempting to document the mental models/workflows that they’re bringing to bear on the situation – will improve their processes as well as making their implicit knowledge available to other team members. Maybe the documented workflow won’t yield entirely the same result, but if it can get a younger team member 90% of the way there – that’s a huge improvement on floundering in the dark.

ORGANIZING

FILE STRUCTURE

How often do your team members struggle with finding the information they need? If the answer is anything more frequent than “rarely” – improve your file structure.

Map out your most common workflows and talk to your team: where are the common issues, areas of conflict and confusion? Every office, studio, and firm operates a little different depending on major project types and workflows. Your file organization should reflect what’s important to your organization. One popular method for thinking about structuring knowledge is Tiago Forte’s PARA – Projects, Areas, Resources, Archive. Looking at how Forte structures information may help you figure out a more effective system for your organization.

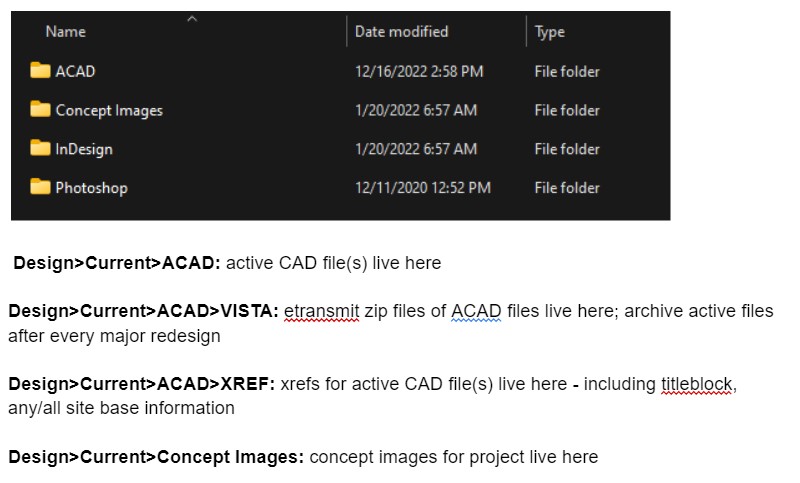

Establish clear guidelines for what goes where within your file structure – maintain a reference as part of your training materials.

LIBRARIES

As a project manager, I’m always trying to identify the annoying tasks that we do over and over again. What are the things that waste our time? Building libraries of preferred design elements is an easy way to reduce unnecessary time. Some examples of libraries to consider include:

Details Libraries – establish standard details sheets and libraries of details. If these standard components are pre-approved by project managers, you’ll have major components of construction documents ready to go.

Image Libraries – build libraries of imagery of inspiration, materials, detailing, and plants. The more of these are pulled from your projects and area of specialty, the better. You can make sure these fit principals’ and project managers’ preferences – that way entry and mid level designers are starting with materials that fit the studio’s style.

Topic Libraries – when you’ve gathered research for a specific topic, make sure that information is available and easy to access for other design team members in the future. Build databases of relevant articles/charts/references for your studio’s common topics. Including small summary documents and office best practices based on research is also an easy way to make knowledge accessible across teams.

STORING

DIGITAL DOCUMENT RETENTION

Yes, much knowledge is stored in your staff’s brains. But the majority of easily reproducible information in any organization is stored digitally. As licensed professionals, landscape architects are required to maintain client records for a period of at least several years – exact duration depends on jurisdiction. Check with your insurance company and state policy experts to understand the duration requirements that affect you. Have a clear office policy about document retention. Follow it.

As part of your document retention policy, work with your IT to understand when, where, and how your office’s digital information is backed up. Understand what happens if someone accidentally deletes something – or file corruption occurs. Redundant backups are essential – typical best practices are to have backups to at least 2 independent locations. The Theory and Craft of Digital Preservation (see Further) has good guidelines to discuss with your IT and ensure your digital information is appropriately stored.

SHARING

PROJECT-SPECIFIC

Do you have a regular practice of sharing information about projects? Schedule kickoff meetings at the beginning of projects with all involved team members to share parameters and establish common expectations. Open communication at the beginning of a project can help set up everyone involved for success. Clearly communicating priorities and expectations help production-oriented designers do work that better reflects that project’s intent. The more individual team members are equipped with the information that they need to make decisions, the happier you’ll be as a project manager. Identify critical paths and decisions to make sure you have the design documents necessary to support client decisions at the next ship point.

TRAINING MATERIALS

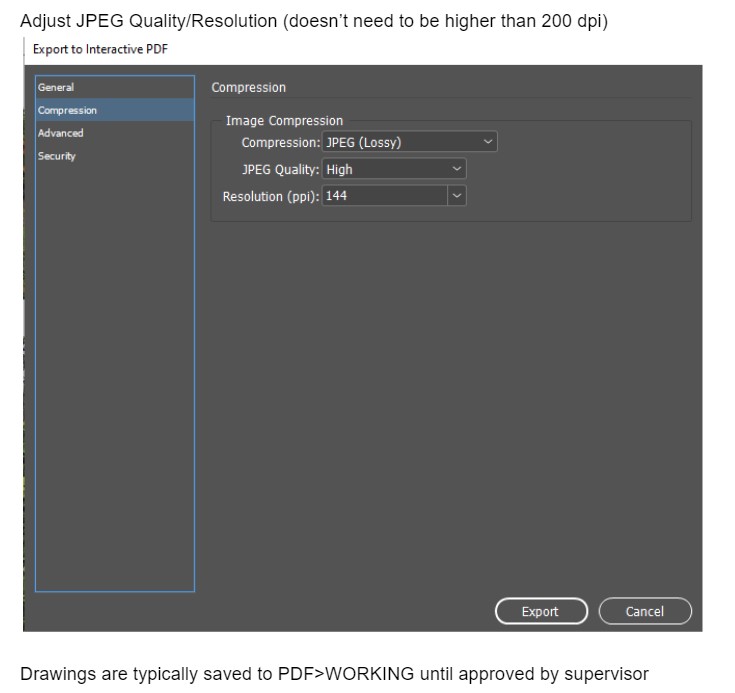

One of the biggest hurdles to entry at any firm is the learning curve. Entry periods are tough for any businesses – and new employees. Figure out training resources that will give new team members autonomy over their learning. Our studio has an onboarding/processes document with step-by-step instructions (with screenshots) for all of our primary workflows. This also allows new designers to check back if they’ve already been walked through a procedure and don’t recall the exact steps. Despite having created the majority of the document, I find myself referencing it sometimes for infrequent tasks – like how to load a plot style on a new machine in AutoCAD or what our principal’s preferred naming system is for downloading site visit photos.

Rather than thinking about creating these training materials as a gargantuan effort that takes away from billable hours, integrate creating this kind of a document while you’re going about the process of a project. It’s easy enough to screenshot and record step-by-step-instructions when you’re already going through a workflow. Do one common task at a time and you’ll soon have a good record of your studio’s preferences ready to share with new hires – as well as ensuring consistency of workflows with your existing team.

Training materials should include specific guidelines for preferred procedures and settings – these should also be easy to search and reference for later use.

SKILLS-BASED SHARING

Establish regular appointments for open learning together as an organization. I’ve heard of some studios who regularly read and discuss self-development or business books. Our studio schedules regular lunch-&-learns where a team member showcases a new workflow that they’re developed or some standard procedure that we’re exploring. As a hybrid team (some remote, some in-person), establishing these points has been helpful and effective. We may not physically be around a table, but we bond around the virtual hearth. Designers can ask for a lunch-n-learn about a topic or workflow they feel uncertain about. Or, they can show off something they’ve been experimenting with – like incorporating Midjourney image generation into render workflows. We haven’t gotten this far yet, but you could video record these sessions and add them to your office library so everyone can reference them in the future.

Drawing together – whether with work spread out on a physical table or across a digital interface – is an effective way of transferring implicit knowledge between team members.

APPLYING

LEARNING-IN-ACTION

We’ve all watched an hour-long youtube training video and emerged at the end with zero information absorption. By contrast, one of the most effective ways of transmitting information is learning-in-action – a process described in detail by Donald Schon in The Reflective Practitioner (see below). Learning-in-action involves a coaching process where 2 or more people work through design problems together. This type of working-through a situation together is especially useful for transmitting implicit knowledge between more- and less-experienced designers.

Scheduling regular times to work through problems together helps make these types of learning situations happen. Especially in working with fully remote team members, I have found that committing to screen sharing and working together – drawing back and forth – is one of the most effective ways to transmit both explicit and implicit design knowledge.

BEYOND THE OFFICE

Becoming known as a thought leader in your community can help position your business (and landscape architecture as a profession) as go-to professionals for action. Many landscape architects are active members of development, planning, and ecology/nature groups – organizations whose interests ally with our profession. Think a little more broadly: who can you collaborate with who may share common interests that aren’t so obvious? Talk to your local gamer and tech groups – they are often fascinated by the potential of collaborating with designers to bring their skills into the physical world. Can you share your work and knowledge with local politicians? What about your regional media and tourism industry? Start on social media, if that’s easier, then build on those connections. Being an expert in public will help build your personal reputation as well as advancing our profession.

FURTHER

As you build a knowledge management strategy for your organization, spend some time with the following 2 texts:

The Reflective Practitioner, (1983) Donald Schön – Old, yes, but still around for a reason: this text presents useful frameworks for understanding how people learn through designing. Especially good for thinking through how to pass on implicit knowledge in day-to-day practice.

The Theory and Craft of Digital Preservation, (2018) Trevor Owens – The intended audience for this book is information professionals and archivists, however it’s the clearest guide that I’ve found for thinking about knowledge management. This book will give you the keys to communicating your team’s needs with IT professionals and making sure your knowledge management practices are working for your organization.

I’ve framed this piece from the perspective of a project manager since people in positions of power have the strongest ability to change their organization’s knowledge management processes. However, if you’re an entry- or mid-level designer, thinking about these practices will help you more effectively ask for what you need to do your job – and position you for stepping into leadership roles. Regardless of your current position, implement the knowledge management strategies presented in this piece, think-with these two texts, and you’ll be on the way to a stronger, smarter, better-informed team.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured

![Beyond Our Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Research and Design for Health [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/coco-alarcon-224x150.png)