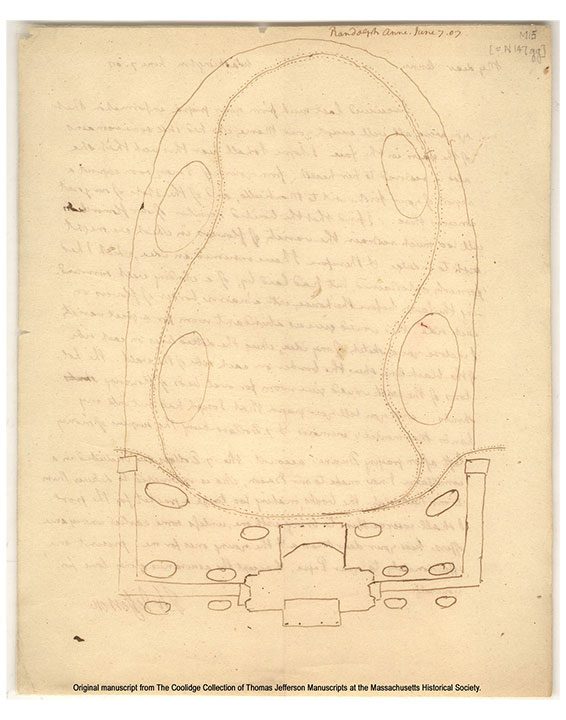

America has an obsession with lush, green manicured lawns. Thomas Jefferson introduced lawns to Monticello after spending five years abroad and taking note of the large, neatly groomed, green swaths at various estates, such as Versailles. At that time, lawns became a symbol of stateliness and wealth due to the demand of resources required for upkeep. Lawns did not become a homesite fixture to the middle class until well after the Civil War. Fredrick Law Olmstead’s public park movement is partially credited with the explosion of lawns into suburban America. Many of the first east coast master planned communities were modeled after parks with shared and individual green spaces. The federal housing boom after World War II further propelled lawns into the mainstream. Homes were built away from the street to provide room for yards as a way to attract homebuyers by mimicking the established homesteads of the upper middle class.

As time went on, the phenomenon of manicured lawns continued to spread on a wide scale as suburban commercial and residential developments boomed. In 2005, it was estimated that lawns covered 63,000 square miles of the United States (roughly the size of Texas). The resources required to sustain these lawns poses potentially devastating environmental impacts. Every year, lawns consume 200 trillion gallons of water. More than 70 million pounds of fertilizer and pesticides are applied resulting in nonpoint pollution in our waterways, and 200 million gallons of gas are used for maintenance, accounting for an EPA estimated 25%-40% of all nonvehicular gasoline emissions. Additionally, manicured lawns are very narrow ecosystems offering virtually no habitat for varying plants, pollinators, birds, or other wildlife.

A MOVE TOWARDS NO-MOW

Fortunately, Americans seem ready for a change. Sustainability is no longer an industry buzz word, and its meaning and principles have been adopted into everyday vernacular. People are continuously becoming more aware of the effects of climate change and the environmental impact of their decisions. Home owners and developers are starting to realize the economic and environmental advantages of transitioning from traditional, regularly maintained lawns to no-mow landscapes. Municipalities and institutions are also converting some of their vast green spaces into no-mow landscapes to reap the benefits of less frequent maintenance.

Image: Clark Condon

No-mow landscapes, traditionally, can be categorized three ways: 1) uncut turf grass that is left to grow wild; 2) naturalized landscapes where lawns are replaced with climate friendly, native, noninvasive grasses and wildflowers; 3) edible landscapes where vegetables and fruit bearing trees are cultivated to replace portions of turf. The National Gardening Association estimates that one in three homes currently supplement their staple foods through home gardens. A fourth option to consider is developing reforestation areas consisting of larger groupings of trees of varying sizes, spacing, and species that consolidate the ground plane into a pine straw or shredded hardwood mulch bed eliminating the turf typically occupying the space between trees. These varying landscapes can offer a textural and colorful aesthetic that cannot be achieved with a manicured lawn.

BIODIVERSITY

A manicured lawn typically consists of only one species of turf grass. Fertilizers and pesticides are used to cultivate the turf to ensure that the targeted grass species is allowed to flourish, while other herbaceous plants and insects are choked out. A no-mow solution of native grasses and wildflowers tremendously increase the biodiversity of the landscape. Native grasses provide habitat for small mammals and ground birds, such as Killdeer and Quail, while wildflowers help reintroduce pollinators like Monarch butterflies and bees, which are currently in global decline. More insects are present, providing food to support wildlife while adding nutrients and aeration to the soil. Reforestation landscapes introduce additional types of small mammals and nesting birds. A more diverse plant selection equates to greater biodiversity in the ecosystem.

Image: Clark Condon

BELOW THE GROUND

Native soils are not intended to support a singular species. Native meadows support plants that are acclimated to the existing soil type. Taproot plants may be prevalent to loosen soils that have high compaction, where plants with more fibrous roots systems dominate loose soils that are susceptible to erosion. No-mow landscapes should utilize plant species that are suited for the existing soil types. Some native grasses may actually have much of their structure below the ground. These hairnet root systems mitigate erosion by stabilizing the soil, increasing water infiltration, and reducing the sediment loss from runoff, improving water quality. These deep root systems also make the plants more drought tolerant, allowing for less watering as these landscapes mature.

Image: Clark Condon

Different plants also carry different nutrients. A diversity of decomposing plant material helps keep the soil fertile and friable. Allowing no-mow landscapes to grow their complete life cycle or just higher prior to cutting them, you are increasing the organic matter being returned to the soil. An additional benefit of allowing these landscapes to mature is that the plants come to seed. This coupled with the additional organic matter eventually makes these regenerative, self-sustaining landscapes.

ECONOMICS AND MAINTENANCE

No-mow landscapes may cost slightly more to install than a traditionally seeded lawn and are not maintenance free. In some instances, the initial maintenance (when establishing a landscape from bare ground) may be more labor intensive than a traditional lawn. This is due to the mechanical weeding needed to ensure the landscape is not overrun with undesirable or invasive plant material and required overseeding to ensure establishment. However, economic and environmental benefits are realized long term. Mowing frequency of no-mow landscapes can be as little as two to three times per year as opposed to up to 44 times per year for traditional lawns in the Houston area. When installed on a large scale, the reduction of energy and resources can be substantial.

Image: Clark Condon

Water savings can be realized instantly with the installation of a no-mow landscape. The initial water requirements for a native grass and wildflower landscape are 25% less than a traditional turf installation. The watering requirements for turf does not wane as the grass matures. Constant watering is required to keep the lush, green appearance. However, an established no-mow landscape may only require supplemental watering, up to ten times per year, to ensure survivability and promote wildflower blooming. Smart irrigation controllers can be utilized to monitor soil moisture and provide watering when it is only necessary.

No-mow landscapes are not going to replace manicured lawns in their entirety, but the ecological benefits cannot be discounted. These differing approaches can be implemented at varying scales that complement the overall aesthetics and functionality of the landscape. The reduction in resources required to maintain a no-mow landscape is real and makes sense, both environmentally and economically.

Published in Blog, Cover Story, Featured

Scott Douglas

This article is missing one major detail about maintenance… Maintaining a no mow planting, especially one with a lot of plant diversity (meadow), requires an educated horticulturist to perform that maintenance. The people maintaining these spaces will have to know what was planted there, what “blew-in” that can remain and what will take over and needs to be removed. The people doing traditional “mow, blow, go” maintenance will most likely lack the knowledge base to do that. This will mean that maintenance is more expensive, as you have to pay more for someone with a degree and/or significant experience to perform the work.

I work at a facility with a well established meadow and it is a constant maintenance battle to keep invasive plants in check. I’d estimate the man-hours are the same if not higher than a turf area and require way more skill than someone riding around on a mower. We can put just about anyone on a mower, but identifying which plants to remove is a different story. Maintenance in these spaces may not be weekly, but they come in big chunks throughout the growing season as different unwanted plants show themselves, often when they begin to flower.

I’m not arguing against reclaiming underutilized turf areas, but I feel like everyone glosses over the true maintenance requirements of these wilder plantings. There was a time when being a “Gardener” was held in high regard, it is time to return that level of status for the people who maintain our built environments.