Author: Win Phyo

Celebrating the 2020 LAF Olmsted Scholars

As we bid farewell to the unforgettable year of 2020, it seems like the right time to reflect on my experience of being a part of the jury for Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) Olmsted Scholars Program. Reflection has certainly been the common theme of our lives as the world’s pandemic shakes us out of our spheres of comfort and normality. We asked more questions than we ever had about our lives regarding our internal and external environments. For the Olmsted Scholar nominees, this may be a part of their experience as they write their 1,000 word submissions.

Each year, LAF asks the following questions as the first part of the essay submissions:

– Describe your personal development and how it has influenced your direction and vision for the future?

– Discuss how you see your role in advancing sustainable planning and design and fostering human and societal benefits.

The program has now reached its 13th year and the integrity of this cause is palpable even from across the globe. Sitting in my home in the UK, I joined my fellow jurors in April and May as we debated and reasoned.

A total of 85 Olmsted Scholars were recognised in 2020. Of these, there were six national finalists (three undergraduate and three graduate students) and two national winners (one undergraduate and one graduate students) – all of whom are recipients of an award and part of a larger community of LAF Olmsted Scholars, going back 13 years! The following paragraphs are only some of the stories from both of this year’s winners and from only three of the finalists.

I have come to an understanding that the foundation for influence and leadership in this profession come from the unique and common stories we each hold and, like an alchemist, transform our stories into something practical and tangible that we can share with the rest of the world.

“Who Am I?”

David Hooper, this year’s undergraduate national winner, spent his former years before studying Landscape Architecture as a photojournalist in the Navy. The deep social connections that stemmed from recording humanity across the globe through his camera became something he valued. He witnessed the power of creativity to transform lives. This ultimately led him to view the interconnectivity of not only being a landscape architect, but also the contributions and achievements he could make through his lens of experience and perspective.

Lys Divine Ndemeye, the graduate national winner, was born in Burundi before moving to Niger and settling in Edmonton. All of these moves from very distinctive places allowed her to see and experience a place being reflective of the systems of political power, social, economical, climatic and cultural complexities: “Unfortunately, I am faced with Landscape Architecture’s frequent exclusion of African and Indigenous cultural landscapes and design ethos.”

Aaron Lewis, one of the undergraduate finalists, formed a relationship with his bike that took his 15-year-old self to football practices, weightlifting sessions, and trips to the supermarket. He grounds these early life experiences and living with his grandparents as a fortunate source of stability – to have been given access to resources, within a childhood reality of being part of a marginalised group.

Audrey Wilke, another undergraduate finalist, shares her vulnerable moments of shame and embarrassment to be in school with dyslexia. Over time, her connection to this part of her weakness became a source of strength as she learned about the unique qualities. As a person with dyslexia, she learned about her strong spatial reasoning, powerful creative thoughts, and insightful connections, which ultimately led to landscape architecture.

Martin Egan, one of the graduate finalists, reveals his concerns for public spaces to provide emotional security and social acceptance, whilst raising awareness of the LGBTQ+ community. A physical attack at a young age changed his perspective and experience of open spaces.

“How Can I Give Back?”

In the second part of the essay, LAF asks the nominees how they would use the funds if they were to win.

With the prize money of $15,000, David plans to study horticultural therapy before seeking to design a curriculum and program that will provide veterans with non-traditional therapy to heal their trauma of war and conflict. He states, “by acting to heal, one is healed.” The program intends to provide veterans with practical skills that can also present employment opportunities.

Lys, with the $25,000 prize money, hopes to promote landscape architecture to Indigenous and African descent youths to “make the future of the profession more apt to design and advocate for the diverse communities we serve.”

By living in marginalised communities, similar to the one he grew up in, Aaron wishes to build case studies of socially equitable developments.

Audrey outlines a best practices guide for truly accessible landscape design, created by the disability community.

Lastly, what would a public space that has full awareness, acceptance and provides a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community look like? Martin hopes to uncover this through a two-day symposium that explores just that.

The graduate finalists received a $5,000 award and undergraduate finalists received a $3,000 award. Although this shows only a snapshot of the 2020 Olmsted Scholars, these examples and stories demonstrate how the profession of landscape architecture and our seemingly small to large contributions can be built from our own personal experiences and personal development. Throughout this process, I found myself brimming with inspiration and smiling with hope and courage. No, I don’t fear the disappearance of such a niche profession that is landscape architecture. I admire the diversity of the representations we have.

The stories of these individuals demonstrate that we are much more than the work we do in our profession. Our personal stories and accounts are not something to hide and stow away in a dark empty closet but to be given the light of perspective, logic, reasoning and practicality.

LAF states that this program is to recognize and support students with exceptional leadership potential who are using ideas, influence, communication, service and leadership to advance sustainable planning and design and foster human and societal benefits.

By empowering ourselves with our stories, we each can take a stronger leadership role and bring more fulfilment to the people, wildlife, and the environment we serve.

Maybe you will be your university’s nominee for the LAF Olmsted Scholars Program next year. Maybe you will reflect on what experiences brought you into the profession. Maybe you will decide to leave a small imprint of your own story in the next project you do, even if no one else can see it.

Learn more: www.lafoundation.org/olmsted

Humanitarianism + Landscape Architecture: Crisis, Commotion and Collaboration

Mapping the Crisis

The world’s first modern atlas emerged in 1570. Nearly 450 years later, Professor Richard Weller, chair of Landscape Architecture at University of Pennsylvania, and his team produced “Atlas for the End of the World”. Atlas for the End of the World uses cartology (mapmaking) to show the world’s situations in the context of issues faced by humanity in the 21st century.

Whilst Weller’s research screams to the viewers of the urgency of a changing world, often it doesn’t become a priority until it becomes critical. [Cue Humanitarianism]. The term “humanitarism” can be as ambiguous as “landscape architecture” because it is perceived to be very broad and difficult to exactly define for many.

The purpose of Humanitarianism is deeply rooted in the following:

- deal with problems in conflict situations of displacement and loss of livelihoods;

- prevent and strengthen preparedness when crises and natural disasters occur;

- alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity during and after such situations.

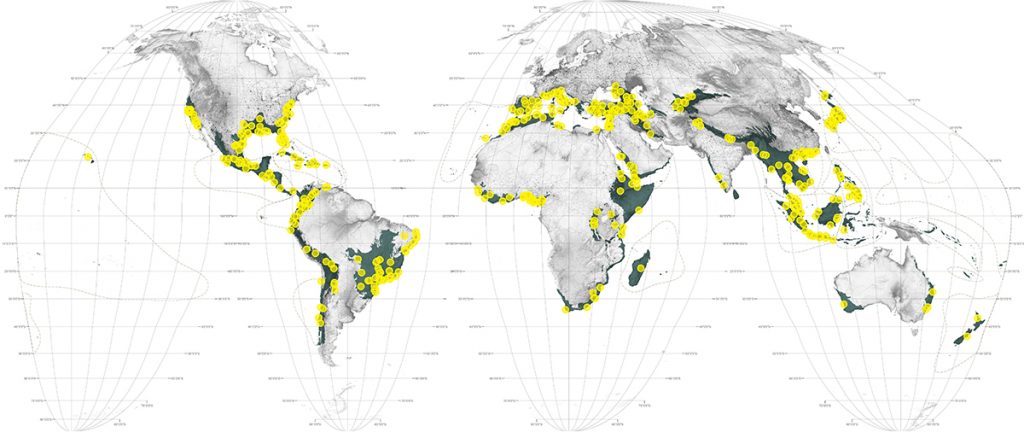

Hotspot Cities are cities of 300,000 or more people that are projected to sprawl into remnant habitat in the world’s biological hotspots. © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com

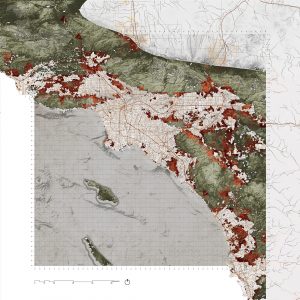

Hotspot City in detail- Los Angeles in US © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com.

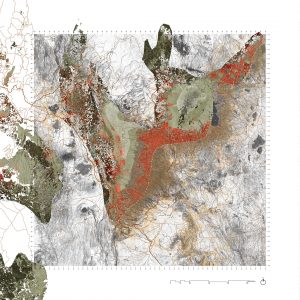

Hotspot City in detail- Nairobi in Kenya © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com

The Moral Dilemma

But why would landscape architects get involved? The Humanitarian Landscape Collective states in their vision statement that landscape architecture has “a professional and moral duty to help vulnerable communities.” Likewise, the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) in their updated Declaration for Concern puts forward that “humanity’s common ground is the landscape itself…that serve a higher purpose of social and ecological justice.” Here comes the moral dilemma – surely, if there is a need to do so as we face rapid urbanization, changing climate, and escalating consumption of Earth’s finite resources, landscape architects should get involved in some capacity?

The System Thinkers

There is an ongoing discussion, which exists outside of the humanitarian context for the need of landscape architects to help create an alternate future. The point here is the same. LAF comments that most humanitarian work has a spatial aspect that can benefit from a unique perspective of landscape architects as “systems thinkers trained to design for natural resources, natural processes and people.” Public health, environmental psychology, sociology, food systems… these are the few aspects in which landscape plays a part of either the main benefactor, the binding agent, or simply part of the cast in the creation of a holistically functioning environment.

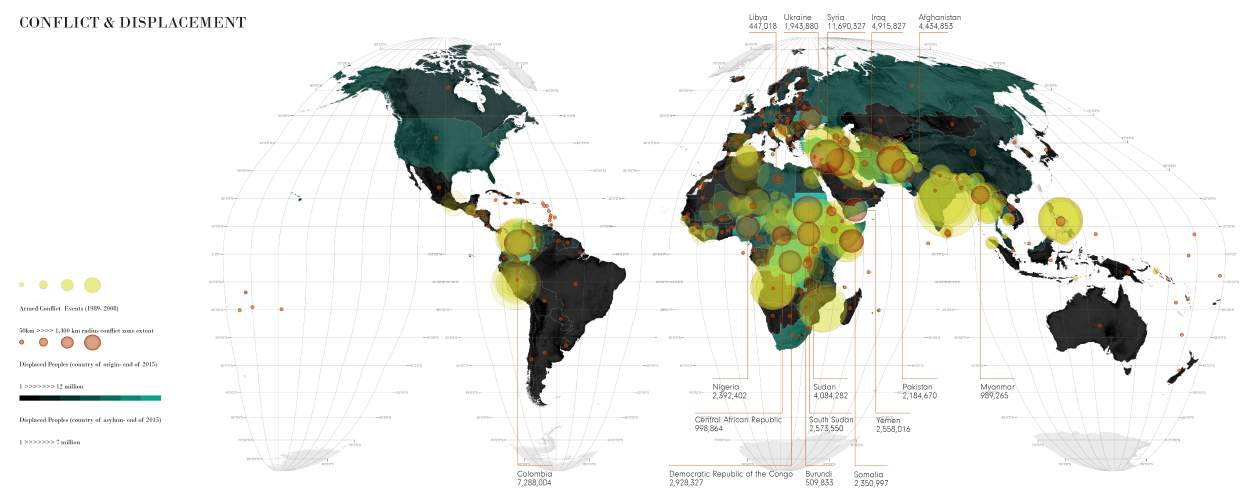

Map showing displacement of people due to conflict © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com

The Seed Sowers

There are already a bunch of system thinkers sowing the seeds to consider our avenues of assistance. The previously mentioned Humanitarian Landscape Collective, based in London, is currently building knowledge and relationships with other professionals to further identify the role of landscape architects in humanitarian work. The International Federation of Landscape Architects hosts a group called Landscape Architects Without Borders on Facebook that engage in interesting news amongst peers.

Likewise, LAF has seen an increasing interest in international and nonprofit work from students and emerging leaders. Their Olmsted Scholars Program, an annual leadership recognition program for landscape architecture students, has had many humanitarian-focused proposals amongst winners and finalists:

“This year, our graduate National Olmsted Scholar Areti Athanasopoulos and finalist Grace Mitchell Tada each proposed to build on their previous work by investigating and developing frameworks for the design of refugee camp and migrant center landscapes.

In 2018, graduate winner Liz Camuti’s proposal involved researching new forms of socio-ecological infrastructure for isolated populations threatened by climate change and extreme weather, while undergraduate winner Karina Ramos wanted to create a physical plan for the growth and development of an emerging town in Peru to guide the processes of informal urbanization…” (LAF)

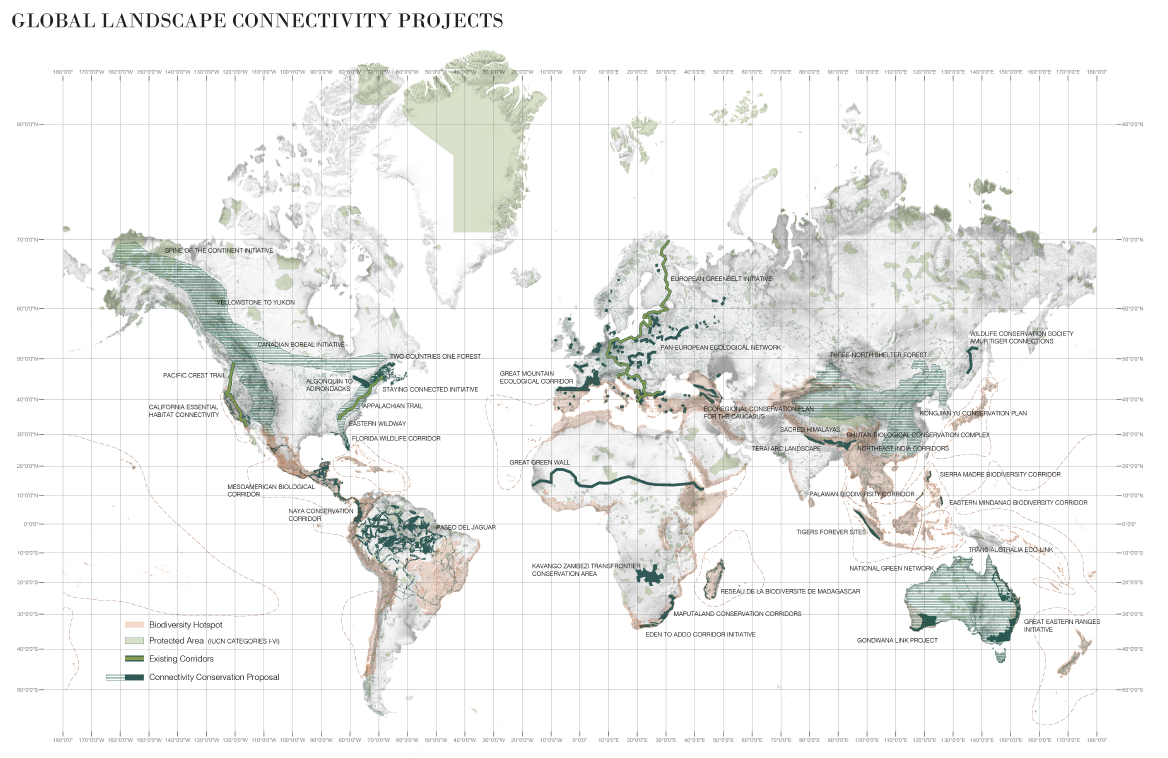

Map shows the proposed and partially constructed large scale landscape connectivity projects across the world, such as restoration, re-wilding projects and provision of public amenity. © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com.

Their $25,000 Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership has also notably led to start up of non-profit organisation Critical Places, that aims to work with people and governments to address critical issues in India, such as water scarcity and waste management.

Marriage of Humanitarianism and Landscape Architecture

Whilst the seed sowers continue to explore and re-define the parallel vagueness of language that exist when landscape architecture and humanitarianism come together, they are going to come to face the inevitable challenges.

LAF points out that the holistic nature of landscape architecture approach might be at odds with how humanitarian work is done, which is a reactionary response to a crisis to address human needs as quickly and efficiently as possible. Thus the long-term impacts and ecological needs can get lost in this scramble:

“The different power actors, goals, and funding sources are commonly isolated, which makes it difficult to address issues in a holistic manner. This is an enormous challenge, but may be all the more reason why landscape architects should get involved.” (LAF)

So What Now?

We once discovered that the world was not flat, and with Weller’s cartology, another revelation is created of the world’s current land use and urbanisation situation. It does feel as though landscape architects are starting to deal with the crisis, creating commotions, and achieving collaborations. And the collaboration really extends to creating relationships with the people that need it during the crisis, to maintain, if not, bring back their human dignity over the course that the crisis occurs.

The inevitable challenges are also deeply rooted in the moral dilemma we face and as such, asking ourselves for the reason of getting involved. Whilst landscape architects as “system thinkers” have the prerequisite skills, humanitarian work isn’t about creating a ministry of do-gooders for welfare and social change. It’s about creating an ecosystem that capitalises on the idealists and campaigners who want to help without building a culture of individual saviourism.

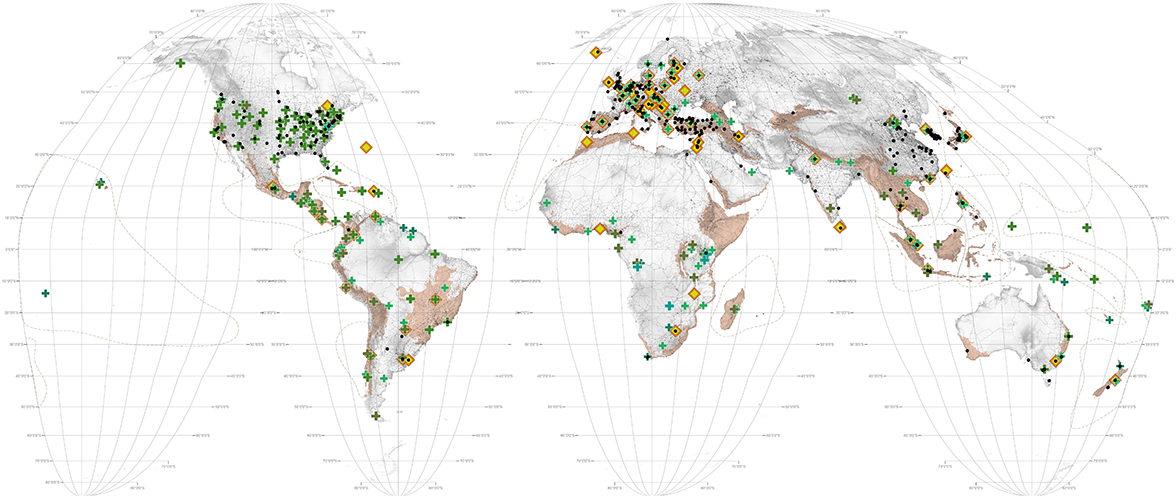

Map indicates location of landscape architectural education programs and big international non-government organisations in the world. It shows that global conservation movement has established evenly in the manner that landscape architecture has not – there is a disconnection between where the subject is taught and where it is most needed from a biodiversity perspective. © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com.

—

Lead Image: © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World, http://atlas-for-the-end-of-the-world.com

We would be interested to hear your thoughts – do you think there is scope for landscape architects to be involved in this type of work? What aspects should be given the most efforts? Where do you see any challenges arising as the profession gets involved?

Bangkok Is Sinking and Here Is the Solution

Just as New York has Central Park, Bangkok has just received its lungs of the City – the Chulalongkorn Centenary Park, the first sizeable green infrastructure project, which has been designed for the city to face the inevitable realities of climate change. We teamed up with the landscape architects of the project, Landprocess, to tell this story in an intimately visual way. Through a series of infographics, maps, diagrams and visualisations, we will be demonstrating the seemingly looming climatic uncertainties of Bangkok and the solutions that Chulalongkorn Centenary Park provides to mitigate these issues.

1. Chulalongkorn Centenary Park (Image: Landprocess)

How is Bangkok sinking?

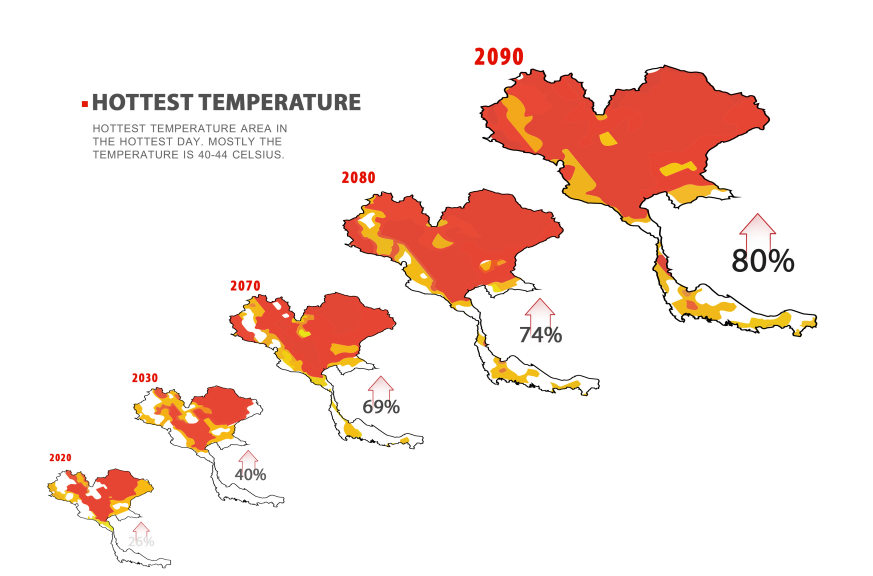

The inevitable reality feels like a distant fate until we explore the figures. Bangkok is not how it used to be and Figure 1 shows the creeping grey fingers of urban development that is eating away the agricultural land. This is a grey city with a lack of outdoor public space. Once upon a time, in the 1900s, the agriculture land absorbed the seasonal flooding and cycles of the monsoon rain. Today, the heavy construction process and designs have not explored ways to deal with climate change. Bangkok is a popular city that is rapidly developing and relies on hard landscape designs.

2a. Chulalongkorn Centenary Park (Image: Landprocess)

2b. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

2c. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

3. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

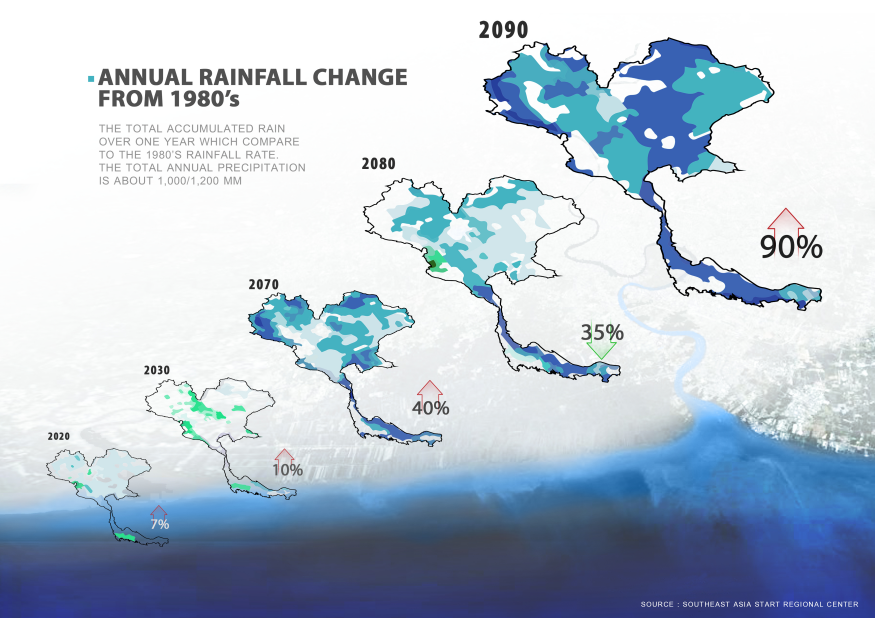

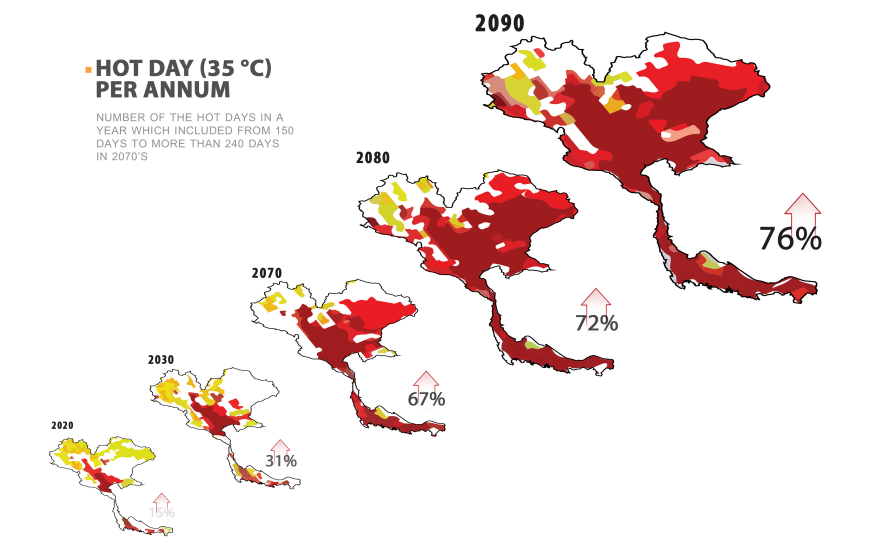

Unfortunately, we are telling the same sad story that most of the major cities in Asia are facing today. This reliance on hard landscape designs have created a city with urban heat island effect and one that is very thirsty for more green spaces and water management solutions. This poses a threat and Bangkok has experienced increased flooding and rising temperatures. For example, the percentage increase of the total accumulated rain over a year, since the 1980s, is expected to increase by 7% in 2020, and by 2090, this will further increase by 90% (see figure 2). That is within the lifetime of the young children of today! Moreover, being at sea level, there is an increasing list of threats from rising seas, storm surge, heavy seasonal and monsoon rain. And as figure 3 shows, there is no permeability for the excess water with an increasing amount of hard landscape.

4. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

5. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

The reality is that Bangkok is slowly and silently sinking. The need for resilient and protective design for today and the future is an essential solution for the city.

The Green Oasis

Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park is located in a major university campus in central Bangkok. As the name suggests, it was 100 years ago that the University was founded and for this celebration, the university has given this commercial area, which connects the campus to the city, to serve as a public park.

Bangkok’s reclaim to its historic waterscape urbanism is becoming more of a reality. The park then becomes an important and shared piece of green infrastructure with pedestrian and bicycle transport links and areas that perform ecological functions. The university’s symbol is the rain tree, which gives a basis for a strong conceptual and literal notion of the tree roots absorbing the water, meandering and reaching out into the city to create a green oasis once more.

Landprocess – Changing Bangkok’s cityscape one site at a time

Landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom is the founder of Landprocess, a design firm dedicated to tackle resilient issues and protect the vulnerable communities from troubling climate change events. Her and her team are advocates for bridging the environmental and social needs, and Kotchakorn also founded Porous City Network, a landscape architecture social enterprise working to increase urban resilience in Southeast Asian cities. Along with the Chulalongkorn Centenary Park, Landprocess has also created productive public green spaces along the floodplain and coastal areas of the city.

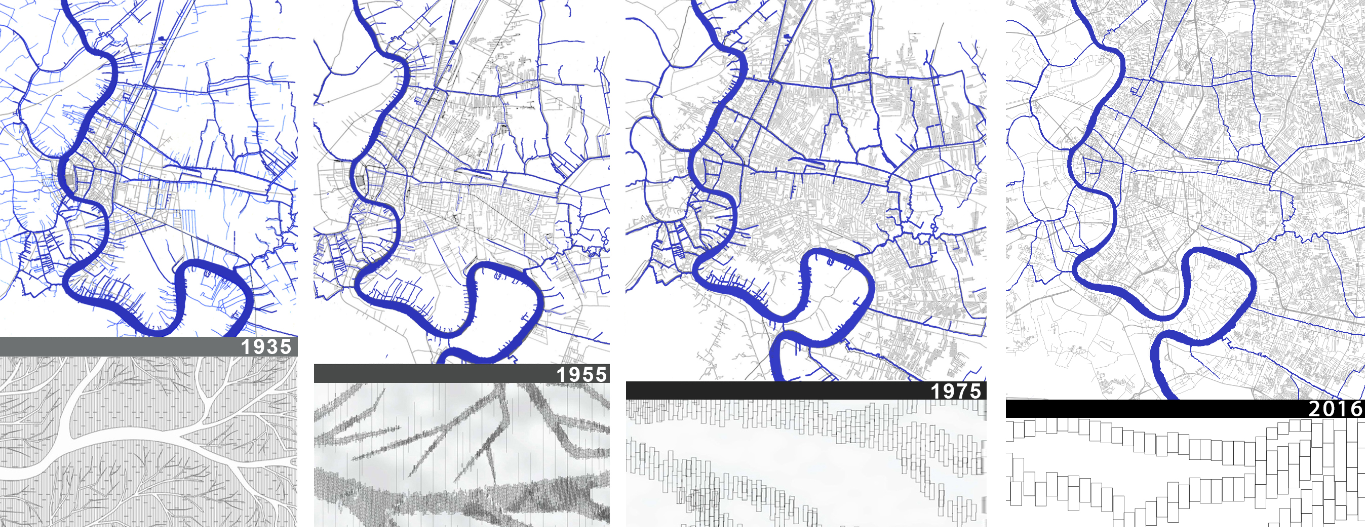

A True City Park

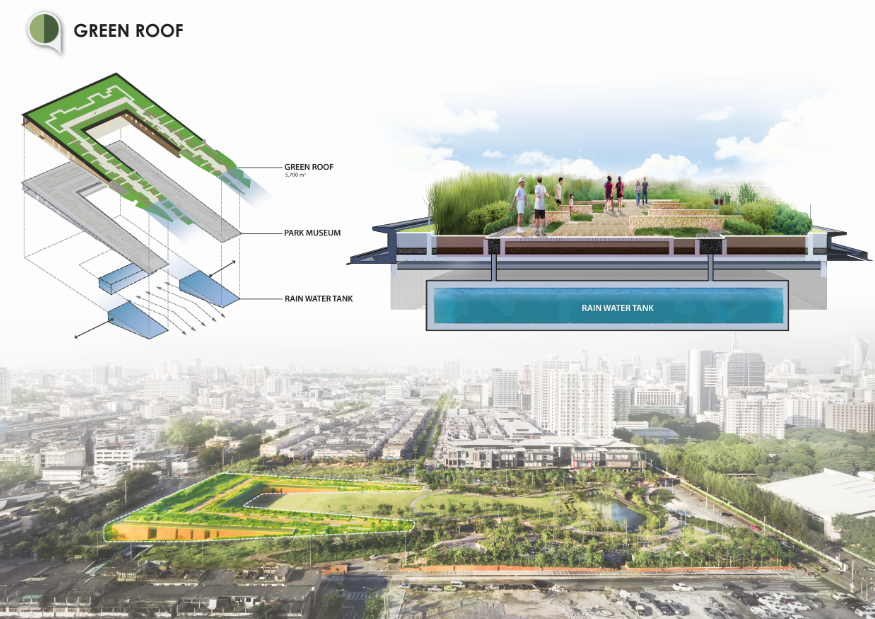

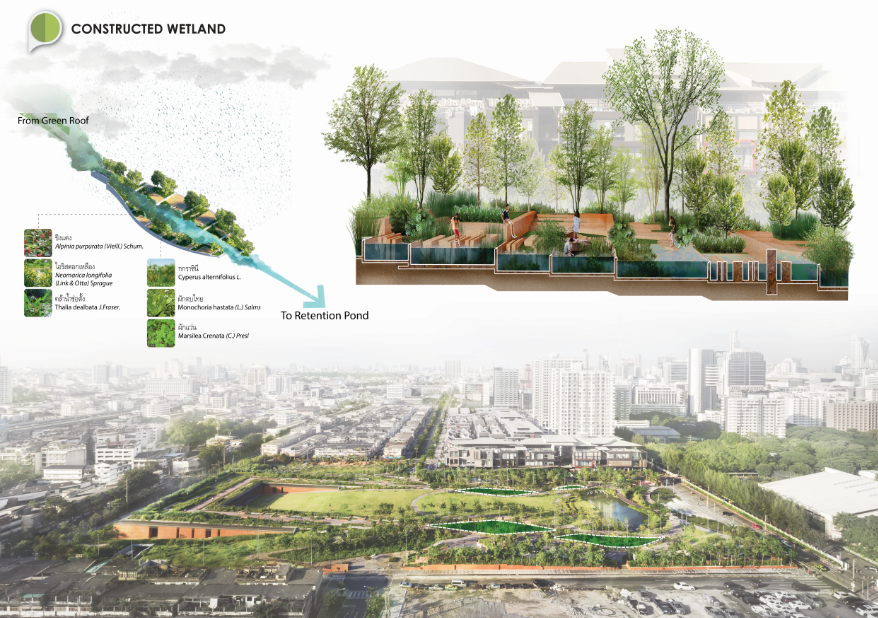

The park is a system that absorbs and control water and provides a green, shady, climatic relief for everyone. The size of the park is about 5ha with a 1.3km green avenue. In order to provide proper water treatment function, there are components that make up the park’s water treatment system. It starts at the highest point, the green roof. Planted with native grasses and low maintenance weeds, they help to absorb water, which is stored in the rain tanks below. The overflow drains to the constructed wetlands, which are along the park’s sloped inclined plane. Features of the wetland are weirs and ponds where the water is cleaned thoroughly before reading to the lowest point of the park: the retention pond.

The retention pond completes the water circulation with the idea that during the dry season, water will be pumped up from the pond to replenish the ponds of the wetlands or irrigation of the plants. The water treatment system also collects water from surrounding neighbourhoods for cleansing and usage for both the park and the neighbourhoods. Interactive water treatment bikes, when ridden, will create movement and introduce more oxygen into the water. This of course will educate and inspire the public.

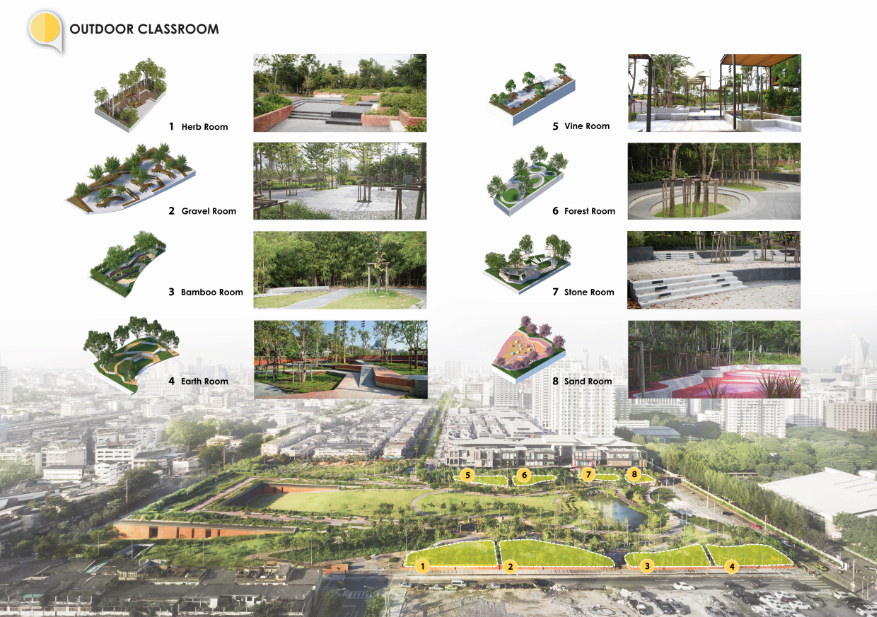

In addition, there are eight landscape rooms, which embody different spatial arrangements and qualities of outdoor classrooms, including programs such as a herb garden, an amphitheatre, meditation walk and reading area.

6. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

7. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

8. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

9. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

10. Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park (Image: Landprocess)

The project highlights some of the most critical situations we will face in cities. Not every city will be able to afford a large space for a park like Chulalongkorn Cenetary Park but there are many other creative solutions, such as sustainable drainage system (SuDS) solutions like swales, retention ponds, pocket parks, urban farming, urban forests, canal restorations and many more.

Sustainability has been a widespread topic over the last ten years and we are heading to the days of resiliency and creating more resilient designs to enable our cities to cope with these changes. Urban sprawl is inevitable and it is predicted that the number of people living in cities will continue to rise. How we handle this is up to us.

If you want to find out more information on how cities can transition from grey to green infrastructure network, head over to Porouscity.org.

Why Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost

Instagram: Wandering Landscape Architect

There is a “Wandering Landscape Architect” currently making a splash in the Instagram scene. If there is a slight anonymity about the page, it is done so intentionally. The creator behind the page is landscape architecture graduate, Emily Sutherland. Having traveled thus far to 18 countries, Emily decided to create a profile on the visually stimulating social media platform three years ago. She recalls, “I’ve always visited many places, and I had so many pictures but never knew what to do with them. So I decided to create this page as a way of storing them for my own reference and to have record of where I’ve been.”

Since then, the Wandering Landscape Architect page has been gaining momentum. In a world of filters, there is a strong sense of authenticity and reality in her pictures. In this interview feature, this wandering graduate talks about the inspiration behind her travels, taking the leap of journeying and feeding it all back into her work.

The Inspiration

“Natural landscapes is the driving factor,” Emily admits. Being originally from the Lake District, England’s largest and mountainous National Park, this is not surprising.

View over Lake Windermere from Troutbeck, 2017 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Lake Windermere from Loughrigg © Wandering Landscape Architect

Stubaiblick Viewing Platform, Neustift, Austria, 2017 © Wandering Landscape Architect

She has just come back from her solo trip to Asia, visiting seven countries in total.

ES: “When I was between Universities, I went on a trip to Thailand and I always knew I wanted to go back.”

Krabi Elephant Sanctuary, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

From idyllic pocket parks of Japan to tea plantations of Malaysia, her childhood journeys have expanded into bigger and further ventures to search for inspiration.

BOH Tea Plantation, Cameron Highlands, Malaysia, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Miyajima Park, Japan, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

ES: “I felt like I got to know Bali and Vietnam best just because I stayed there much longer (seven weeks each), which I think is a big part of liking somewhere. With Vietnam, I started from the south and slowly worked my way up to the north.”

Water Temple, Bali, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Indeed, her journeys have a twist and her profile describes her “wandering the globe in search of inspiration.” Part of this process is to soak in the atmosphere.

ES: “Gardens by the Bay, for instance, I went to everyday for about three days in a row and probably spent more time there than the average person would. I can happily sit and watch the world go by.”

Super Trees at Gardens by the Bay, Grant Associates © Wandering Landscape Architect

As organised as her page may look, Emily takes a loose approach in translating the visual content. She is quick to point out, “I don’t think it’s a travel account and I try not to edit my photos too much. I don’t photoshop them. I might up the saturation and exposure, but I never change the image.”

Cloud Dome at Gardens by the Bay, 2018, Grant Associates © Wandering Landscape Architect

She adds, “I try to do it as soon as possible so that it’s still relevant but I don’t force a too strict schedule on myself.” As a result, her images seem tangible and within reach. It is this philosophy that makes the Wandering Landscape Architect page one of the most realistic and authentic pages on this social media platform.

Restaurant Garden, Hoi An, Vietnam, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

ES: “As it has grown, I’ve liked the social side of it. From other landscape architects and travelers, you find out things. It is actually a social world.”

This inspiration is displayed for different groups of people from not just Landscape Architects but also travelers and Emily’s nearest and dearest. Most of us can relate when she remarks, “None of my friends know what we do!” Certainly, as her page has grown, it has become an accessible tool for the public to see the projects designed by landscape architects.

ES: “I have some friends that follow it and said they had never realised that this is the kind of work I do.”

There’s not enough done to get our profession understood in terms of what we do and using social media hopefully will become more common. Some companies have picked up on its importance but I would push it a lot more. – Emily Sutherland

The Journeys

When speaking about doing the journeys as a solo female, Emily openly shares her experience in creating a community through staying in Hostels, making new friends and looking out for one another.

ES: “It was a bit daunting at times, I’m not going to lie! But I am a pretty sensible person. I was always with a group of people and rarely on my own.”

Ha Giang Pass, Northern Vietnam/China Border, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Ha Giang Pass, Northern Vietnam, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Travelling as a solo landscape architect is a different story and Emily points out another relatable point.

ES: “When I would go visit a landscape, I would like to spend a longer time there and enjoy it longer than most people would.”

Creating communities of her own along the way hasn’t led Emily to remain closed off and her trips have also been about connecting with communities.

ES: “When I first arrived in Bali, I did some conservation work, and I worked in a sea turtle conservation organised by local people and volunteers and got a chance to speak to them, see their point of view, and how they used the land. That was probably when I got to know the locals the best.”

Turtle Sanctuary, Release Day, Nusa Penida, Bali, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

The experience has also raised her environmental awareness as she recalls, “We also did a lot of beach cleanup. We would clean the beach everyday and find the same amount of plastic each day. It was quite eye opening.”

Her wandering journeys are kept as flexible as her Instagram posts.

ES: “I would normally go to a recommended place while keeping a flexible schedule and once there, I would research projects nearby. For example, I would ask people if there are any nice gardens. Quite often, I would stumble across special places, especially in Asia where there isn’t much publicity.”

Abandoned Waterpark Hue, Vietnam, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

ES: “I am glad I didn’t book much because most of the travelers I met didn’t book much either and we went with the flow. That meant I could stay somewhere longer if I liked it. If I didn’t, I could leave and I would try to get cheaper plane and bus fare and let that dictate a lot of my trips while keeping the cost down.”

She confesses that she wasn’t always like this and that travelling taught her to go with the flow. Her wandering trips also led Emily to certain key projects along the way such as visiting Singapore to see Gardens by the Bay or going to Japan to see some Japanese gardens.

Souvenir Shop Garden, Miyajima, Japan, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

The Work

Indeed, our widespread professional field allows us to find inspiration in almost every place we travel and ultimately for Emily, her ventures have paused for now to enable her to do some saving and gain further work experience. She’s no stranger to the workplace, having worked across the different stages of work from planning to construction, she has a realistic view.

ES: “There’s so much to learn and you realise how much you didn’t know until you start working. In this day and age, people don’t just have one job, they can be in multiple roles. Our profession may be a bit slow on the take of that because we have quite a lot of traditionally-minded people, and at times it might not be geared up for part time work or flexible schedules. It’s interesting. But it is inconsistent work and we need money, so you have to be consistent! Certainly it is still something I am figuring out.”

Chelsea Flower Show, Cloudy Bay Garden by Sam Ovens © Wandering Landscape Architect

She enthusiastically talks about her student research to design for homeless people as her Masters thesis.

ES: “I did my thesis on homeless people in the landscape and I had the opportunity to interview a lot of vulnerable people. It was called ‘Homeless People and the City.’ You see a lot about defensible architecture these days and we explored ways to help homeless people, including speaking to them about how they used the space, why they pick the areas where they sleep, what they need immediately, what are they lacking, types of lighting that’s best for them, etc.”

Her dream project?

ES: “Community led, high level master-planning of a deprived community with unlimited funds because we are in an imaginary world of course! That’s the dream.”

Suica’s Penguin Park, Tokyo, Japan, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Suica’s Penguin Park, Tokyo, Japan, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

Eventually, it becomes clear that her ultimate goal is far more complex than she had anticipated, which is essentially to integrate into one job, a space for: pushing for public engagement and awareness within the profession, running a practice which creates designs for communities that need it rather than want it, and continuing practical knowledge and inspiration! Certainly, this is a loaded mission and the conversation turns to millennial generation’s approach to job seeking.

ES: “Our generation asks what can this company do for us rather than the company saying what we can do for them. We kind of switch it around. We are probably fussy about where we work! In London, people seem to move around a lot more between practices. There is less loyalty to a company almost. You don’t hear of people staying somewhere for 30/40 years, I don’t know why that is but I do find it interesting. The fact that I was at my last practice for two and a half years, they thought was quite a small amount of time.”

Emily encompasses a fine balance of the inspired, relatable, and practical adventurer and no doubt we can find ourselves in the snippets of her experience and thoughts. Undoubtedly, the journey hasn’t ended for her. The current step is to find a job, which will enable her to save and travel to more places. She is keen to take more short trips in between working life and, in her true wandering style, is keeping these plans flexible.

Kokyo Higashi Gyoen Gardens, Tokyo, Japan, 2018 © Wandering Landscape Architect

The Wandering Landscape Architect page is not only a source of public outreach, but also a reminder that there are wonders to be found in incidental and planned journeys. It is also a celebration of the work of landscape architects whose profession can most times be so subtle that its importance is overlooked.

If you want to know where the Wandering Landscape Architect journeys to next and to add a pinch of inspiration to your day, follow her on Instagram at Wandering Landscape Architect.

Podcasts in the Spotlight: 10 Brilliant Shows for Design Enthusiasts

In 2017, 112 million Americans listened to a podcast and 42 million listen to a podcast on a weekly basis. This amounts to 15% of the total US population, which is five times more than weekly visits made to the movies.

“When you talk, you are only repeating what you already know. But if you listen, you may learn something NEW.” – Dalai Lama

The reason why podcasts are so popular is because most of us want to learn new things and broaden our knowledge base. They are the 21st century’s offline radio. Podcasts can be a great tool for landscape architects to keep track of current trends and topics, feed new vocabulary to your brain, or give you a deeper perspective of the world.

Next time you are doing research for a project you should take 30 minutes out of your day, possibly on your commute to work, to listen to one of the podcasts listed below, they just might help you connect the ideas and make better-informed decisions.

1. 99% Invisible

This highly commended podcast is all about unnoticed architecture and design. While not directly related to landscape architecture, it will teach you about the history and information for things that shape our world, such as how air conditioning was invented or what research tells us about creative scientists and artists. It is basically a fact bomb for the curious. The shortest episode available is only seven minutes long and the longest is 30 minutes.

In a recent episode, 99% Invisible teamed up with VOX to create a visual podcast that talks about biomimicry and how designers should be bringing biologists to the table for the purpose of solving complex human problems.

Recommended Episode: “Biomimicry”

2. Infinite Earth Radio

This podcast is dedicated to exploring one of the trendiest and most important issues of our time — sustainability. Every week, there are 30-minute interviews with forward-thinking individuals who are actively taking part in building smarter, more sustainable, and equitable communities. They stem from government officials and local organizations to savvy businesspeople. If you are dedicated to this topic, you will be blown away by the wide range of directions each takes.

Recommended Episode: “Authentic Community Engagement in Gentrifying Communities”

3. The Sod Show

Hosted by horticulturist Peter Donegan, the SodShow Garden podcast host interviews several personalities across the industry. The 30-minute interactive episodes are very informative for tips and tricks on garden design. You will also find the podcast entertaining and moving.

Recommended Episode: “Live, Salt Lake City: Fritz Kollmann, Red Butte Garden. Thyme and Place”

4. Common Edge

This podcast is brought to you by the non-profit Common Edge to connect architecture and design to the public that it is meant to serve. Each episode lasts around 30 to 50 minutes and reports on public engagement in planning and design of the built environment. If you are interested in sociology and design, this would be it.

Recommended Episode: “Landscape Architecture in the Age of Climate Change”

Image courtesy of Local Office Landscape Architecture

5. The Landscape Architect Podcast

This podcast connects the voices of landscape architecture and hosts interview prominent landscape architects of our time. Each episode is a pleasant listen, recorded with stories, intentions, and impacts of contemporary landscape architecture. The lengths of each episode vary from 20 to 55 minutes. If you want to know the thoughts and ideas behind the minds of leaders in landscape architecture, this is a great starting point!

Recommended Episode: “Feng shui and Landscape Architecture”

6. Homeland Lab

Here is a topic that we do not normally come across in our daily lives: what is the profound relationship between homelessness and public space? The podcast explores the spatial manifestation of homelessness on the landscape and features politicians, designers, public space managers, and researchers to help foster better spatial strategies for everyone. Each episode length varies from 30 minutes to an hour.

Recommended Episode: “Reflections 1”

7. In Defense of Plants

For the plant geeks inside us, if you want a more technical, science-related podcast, this is it! The knowledgeable host tells stories about the smallest duckweed to the tallest redwood, sharing his love for plants as we take a peek inside the botanical world.

Recommended Episode: “For the Love of Growing Plants”

8. The Urbanist

As the name suggests, this podcast is dedicated to cities and all things related to our urban environment. The weekly show, with each episode lasting 30-minutes in length, talks about what makes cities work or fail. The episodes are fascinating and give a global perspective by covering major cities such as Rio, London, and Dubai. We also get an insight to current innovative solutions that are trying to tackle urban problems.

Recommended Episode: “Land reclamation and prizes”

Image courtesy of Heatherwick Studio

9. Placemakers

From a global perspective with The Urbanist to a communal perspective, Placemakers zooms into the stories of people that are shaping the community that they live in by solving complex issues from the bottom up. This podcast is very real and has a strong “Power to the People” feeling. Each episode ranges from about 20 to 30 minutes in length.

Recommended Episode: “The Greatest Misallocation of Resources in the History of the World”

10. Remarkable Objects

Remarkable Objects is an outstanding podcast that looks at the intersection between natural landscape and urban design and how they both shape one another. With an average running time of 20 minutes, the episode topics are advanced in thinking. They include interviews that explore how including nature in our cities will create a more beneficial future for all.

Recommended Episode: “Quantifying the Landscape”

View Remarkable Objects recaps: land8.com/podcasts

BONUS: America Adapts – The Climate Change Podcast

Land8 has promoted this podcast previously, which hosts some of the most innovative and leading adaptation thinkers in the country to talk about how we as a society should adapt to climate change. The host of the podcast made a special trip to the ASLA Meeting + EXPO in Los Angeles. Listen below to hear his insights and takeaways from meeting with many in the landscape architecture profession and industry.

Recommended Episode: “Landscape Architects Adapt to Climate Change”

The podcasts listed above are a testament to smart technology becoming a positive source of influence. Within a relatively short amount of time, you can connect with community activists bringing important changes to their neighborhoods, learn about equitable development from a Professor at the University of Southern California, hear a landscape architect speak about design of commemorative landscapes, and so much more! We are interested to hear what you think about our recommendations.

Lead image: Elizabeth Quay in Perth, Australia courtesy of Peter Bennetts

This Beautiful Model District is Raising the Quality of the Residential Market in China

Development in China is known to happen very quickly. Imagine the intensity of the design process from project conception to construction, which amplifies the importance of getting it right within a small time frame. Vanke Huafu Mansion Model District has done just that. Vanke Mansion Real Estate’s brand is one that promotes elegance and zen spirit of traditional Chinese mansions in a contemporary manner. The design direction was not only to design the low-density high quality residential development itself but also, more importantly, to design the main entrance area of a future residential community and the sales center within the ancient Chinese capital of Xi’an. Resolving practical issues of circulation satisfy the residents and visitors to the sales center. As the saying “You never get a second chance to make a good first impression” goes, the designers had a heavy task at hand.

What Makes Up the Zen Spirit of This Place?

There are many ways to approach this curiosity, but in this context we can pick up a sense of quiet rhythm. If a place could resemble the soft tones of a piano, this would be it. Users are led down to this quietness through a sequential approach. Circulation is divided via a series of courtyards, carefully arranged to take them down from a loud urban surrounding to a tranquil community area, transitioning from this bustling urban town to an exalted mansion.

This zen spirit is also represented through sculptures. The stone sculptures, which we will come to discuss later, add an earthy element to the place. They are solid-grounded and rooted so majestically that the place further radiates an inner peaceful quality.

Following the Traditional Ways

In the ancient times, common people lived in houses that shared one or two courtyards. Houses with three courtyards only belonged to nobles. To create this rich and majestic sense, the design follows the three courtyard tradition. This provides a grand entrance, bringing a sense of ritual. However, a courtyard atmosphere is also very communal and can be interpreted as a welcoming return to one’s home. The Gate, one of the three courtyards, is a luxury mansion with a repeated gateway entrance. The Courtyard, the second of the three, has a square water pool that reflects the sky and clouds.

The last courtyard, Mountain Hall, includes a 25-piece yellow sandstone mountain sculpture on a mirror of flowing water representing a metaphorical concept of Qinling Mountains.

Qinling Mountains sit adjacently to the south of Xi’an City. The notorious mountainous region, also known as the “Szechuan Alps,” create a natural boundary that divide the northern and southern parts of China, which brings more significance to this sculptural reference.

Around the doorway just after the courtyard series is a smaller courtyard for the marketing suite, which is used to showcase the district. This space, in particular, has been divided into several pieces. As it currently lacks activity, the area will be used for marketing but from abandoning the traditional vacant lawn design, it becomes a multi-functional space.

Thinking Ahead…

The first model house or “Outdoor Sanhao Mansion” is located after the courtyards. Being the furthest away from the urban town and as the last space, Sanhao Mansion is truly serene in nature and provides an exemplary outdoor space for future development.

The scale of the external area is designed to even ensure that the grass area can be mowed comfortably, including satisfying the requirements for a cultural gallery function for the future community. In order to strengthen the zen musicality within the courtyard, the designers have replaced traditional community planting with a floating evergreen planting pool, made out of a curved aluminum board. A group of mountain-cloud themed sculptures also sit within the middle.

A Subtle Kind of Beauty

There is a sense of purity and innocence within the project because a subtle language of poetic design starts to be formed by the materials and the rhythmic layout. An example is the “cloud” and “mountain” stone sculpture that is combined with the effect of fog and lighting to create a sensory experience.

You can catch the trunk and narrow branches of the young trees casting patterned shadows on the vertical and horizontal elements that narrate the transient beauty of nature and its cycles.

It is exciting to see the emergence of residential development of this quality — one that is contextually well considered and brings forward the design of outdoor areas to the forefront of the overall scheme. The clever conception of the project is building the sales center (a model home to allow prospective buyers to explore the design of home) first with exemplary spaces. This sets the standard and the notorious rhythmic tone for the future housing area.

The artistic sculptural quality of the scheme also contributes a charming layer of aesthetics that is not usually associated with residential developments. This is what makes it unique. This project makes the perfect “first impression” that is so important in today’s design world.

Project Information

Project Name: True Love, Vanke Huafu Mansion Model District

Project Address: No.4 Heyanqu Road, South Park Road, Xi’an City, Shanxi Province

Project Area: 5000 ㎡

Date: March, 2017

Completed Date: July, 2017

Developer: Vanke Real Estate

Design Firm: FLO Landscape Design Company

Design Team: Kai Fu, Lei Guo, Lixing Pan, Shiqian Luo, Jianhao Sun, Xiaoyin Wang, Shuyi Zhang

All images courtesy of FLO Landscape Design Company.

Garden Designers and Landscape Architects: Resolving the Identity Crisis

We explore the key differences between a garden designer and a landscape architect. When is a garden designer a landscape architect/designer? Are they rivals or are they on par? This article is mainly inspired by conversations I have had with those outside the profession, unfamiliar with the scope of work of a landscape architect. Landscape architects/designers often get confused with garden designers, however the questions that are being asked above are not the right ones. This is not a written piece on comparison of skill or qualifications, but meant to address the right questions and consider the importance of answering them. Behold, the following paragraphs will resolve this identity crisis by revisiting the root definitions and exploring the fundamental aspects, context, and history in how this confusion started.

What Defines a Garden?

One way of seeking definitions is by examining what makes up a “garden” and a “landscape”— what are the fundamental prerequisites and what does it mean to work within these contexts? How would you define a garden? Here are a couple of definitions from the web:

- An enclosed piece of ground devoted to the cultivation of flowers, fruit or vegetables (Oxford Dictionary)

- A piece of ground adjoining a house, used for growing flowers, fruit, or vegetables (Collins English Dictionary)

Hilgard Garden in Berkeley, California. Credit: Mary Barensfeld Architecture

The common elements that frame both definitions are: a garden has boundaries and that involves the act of cultivation. “An enclosed piece of ground” suggests that a garden has distinct limits to space. The intervention is very apparent and without human intervention, gardens would ultimately revert back to landscape.

In a poetic way, for something to be considered a garden, there has to be a gardener and there is often the creation of an idealized other space, separated by its boundaries from the existing (or wider) landscape. Designing a garden can, most positively, often get away with this.

The Winton Beauty of Mathematics Garden in Chelsea, London. Credit: Nick Bailey

What Defines a Landscape?

Landscape has looser limits where boundaries are concerned and often there are no distinct limits at all. A landscape is essentially already there. Landscape design is clearly the design of the landscape, right?

In essence, landscape design involves the act of intervening (be it subtle or radical) and the qualities of the existing landscape are always the starting point of design.

There is one very simple definition of landscape, which I resort to use every single time:

“anything that is not in a building.”

By this definition, a garden can be defined as a smaller proportion of the bigger landscape. However, garden design, in its own right, is not a branch of landscape design or vice versa. With this view, landscape design can be considered as an umbrella profession with coverage to a range of areas of expertise. Like in medicine or law, landscape architecture covers landscape planning, environmental impact assessment, landscape character analysis, strategic master planning, etc.

Central Park is the most visited park in the United States. Credit: Rob Boudon via CC BY NC-SA 2.0

Consider the following points of how landscape design can vary from garden design.

- Scale: Landscape design covers projects that are generally of a larger size

- Context: Gardens are normally associated with a building but landscapes do not need to be

- Boundaries: the boundaries of a landscape are often blurred in comparison to a garden with defined boundaries

- Activity: There is an element of tending to gardens, which can apply to landscape in terms of management and maintenance, but is often a less important element.

- Audience: Due to landscape design projects varying in scale and context, a designed landscape must accommodate a larger and varied mass of people. For example, projects range from parks, campuses, cemeteries, commercial centers, resorts, transportation facilities, waterfront developments, plazas, and other projects that help define a community.

The High Line is among the most Instagrammed places in the world. Credit: David Berkowitz via CC BY 2.0

The History of Gardening

Forest gardening is the oldest form of gardening from prehistoric times, which began as a method of securing food in tropical areas where useful edible plants were identified and grown in successive layers to create a woodland habitat over time. Then, enclosure of outdoor space began around 10,000 BC, mainly perhaps to keep the animals away.

Within established civilizations, wealthy people began creating aesthetic gardens. Egyptian tomb paintings suggest that they had lotus ponds and symmetrical arrangements of acacias and palms; Persia was also said to have paradise gardens. The wealthiest Romans also built extensive villa gardens and water features. Meanwhile, the 4th century AD saw the rise of Asian garden traditions such as Zen gardens. In Europe, the successive years gave rise to changes from Italian Renaissance gardens in the 16th century to romantic cottage-inspired to wild gardening in the 19th century and modernism in the 20th century.

Gardens of Versailles by André Le Nôtre exemplifying the French formal garden style, popular in Europe until the 18th century. Credit: Kimberly Vardeman via CC BY 2.0

The Landscapes of Today

Today, part of designing a landscape involves designing a lifestyle and tackling bigger issues that revolve around the concerns of modern life. In the 21st century, we are full with environmental consciousness and sustainable practices, for example green roofs and rainwater harvesting, which are becoming more widely practiced.

Waverley Gate Roof Garden in Edinburgh, Scotland. Credit: Jo Hanley

Concepts such as tactical urbanism and placemaking are also something landscape designers can get involved with to help shape local and city-wide neighborhoods and gardening spaces. Moreover, there are landscape designers that are now working with medical professionals to help reduce stress, boost immunity, and promote physical activity.

Today, a landscape may not even incorporate plants. It is surrounding where we live, it can perform different tasks or simply be there to provide rest, while enjoying its forms and shapes — although they have not originated from plant material.

PARK(ing) Day 2016 at Sendlinger Straße in Munich. Credit: Michaila Kühnemann

What’s the Big Deal?

Overall, from the explorations above, the area of overlap between garden and landscape design is not as large as you might first think. Historical advancements show the evolvement of what was in the past considered garden design, which has evolved from human intervention with the landscape for production and with wealth into aesthetic purposes. Times have changed to develop these practices into a wholesome perception of landscape design that now starts to understand systems and biological components on a larger scale.

So, a few questions remain. Does landscape design provide a training — or a state of mind — for a more widely applicable skill set? If so, how can the profession market itself to be taken more seriously and more widely? Perhaps I should leave it to the rest of you to figure this one out.

Recommended Reading:

- Award Winning Small Garden Design by Win Phyo

- 30 Reasons Why Landscape Architecture is More Important Than You Think by Lidija Šuster

- Top 10 Landscape Architecture Projects 2016 by Win Phyo

Featured image: Gravetye Manor Gardens by William Robinson | West Sussex, England | Gravetye Manor | 2014

Landscape Design Software – Which is Best?

We investigate which landscape design software should be on your radar if you want to use the best program out there. Are you a techy person, interested in using design software? Want to stay on top of the landscape architecture game? Here at LAN (Landscape Architects Network), we have offered several articles that dive deeply into this subject: Ashley Penn has given us the essential guide to a range of landscape design software options to suit any budget and writer Paul McAtomney has also given the low-down on some of the top 3D modeling software. The following list is of the top landscape design software programs that you should definitely be using or at least trying out throughout your student life and professional career. We will take you through the best options, used by some of the top companies, from initial line drawings to renderings to making final edits and finally, the layout.

The Best Landscape Design Software

1. AutoCAD

Let’s start off with landscape design software that has never left the top trending list: AutoCAD. We have all used AutoCAD from our beginner student years, right through into our professional careers. It is a versatile program that can be used as a stepping-stone to 3D modeling software like SketchUp. In fact, transporting AutoCAD line drawings into SketchUp to produce simple and quick 3D models has always been a dependable and efficient technique. WATCH >>> The SketchUp Connection Process between AutoCAD and SketchUp for Landscape Architecture Design

2. Vectorworks Landmark

There has always been a debate between the preference of using Vectorworks or AutoCAD. If you have used both, you can let us know what you think of the two options. Vectorworks may not be the industry standard but it has been growing in popularity in many landscape companies. This is due to its versatility and ease of use, which allows you to work in 2D and 3D, as well as having industry-specific features like a parking tool or even its own plant database. If you try this out, you won’t be missing out as there are options to import and export drawings from other programs such as AutoCAD, SketchUp and 3ds Max. WATCH >>> GSG – Vectorworks Landmark 2016 – Introduction

3. Adobe Illustrator

Adobe has brought out many software options that are great for the landscape profession. Adobe Illustrator is a great one for line works; for example, you can easily edit the separate lines on a PDF drawing, which you import into the program, as well as exporting it for other programs like AutoCAD. Likewise, you can make beautiful diagrams, maps and other graphics such as infographics using this program. WATCH >>> Creating A Map With Illustrator – Drawing a river with a variable width

4. Sketchup

Sketchup is another one of the popular and useful tools that has been used worldwide in many design professions including landscape architecture, since it came out in 2000. It is a versatile 3D modeling landscape design software with many plug-ins that allow its users to turn their initial simple 3D models into cool, crazy and beautiful works of art. WATCH >>> landscape architects, garden design – sketchup

5. Lumion

Widely used in some of the larger multi-disciplinary firms, Lumion is a popular program amongst architects. It is also becoming commonly recognized in the landscape architecture world as a 3D rendering program that is easy to learn, whilst producing fantastic results. You can check out this article that explains how this landscape design software can help bring your design ideas to life. WATCH >>> Lumion 6.0 Launch Trailer

6. Autodesk 3ds Max

3ds Max is used in the industry to produce professional and realistic 3D renderings and animations. It is one of the more challenging programs to master but it is a highly regarded landscape design software. Although it is a high-end product that is mainly used in professional environments, for the techy landscape architects out there, it is a worthwhile program to learn. WATCH >>> landscape design making by 3d max and Render by lumion

7. Rhino

Rhino is part AutoCAD, part 3D modeling and part illustrator software that can be used to create beautiful line work for quick 3D graphics. With an even cleaner finish than SketchUp, there are many tutorials out there that can give you the tools you need to achieve a clean 3D model. WATCH >>> Modeling a landscape in Rhino 5

8. Autodesk Revit

Revit is still relatively uncommon in some of the smaller firms but the bigger multi-disciplinary firms are using the software as the popularity of BIM (Building Information Modeling) increases. The software is not tailored particularly well for our industry but it can be used to create great terrain models or detail works. It allows the flexibility of working in plans, sections and 3D visuals all in one go and can provide more information than AutoCAD. If you are interested, there are many tutorials that can get you started. WATCH >>> Siteworks for Revit

9 . Adobe Photoshop

What would we do without Adobe Photoshop? This is another versatile and high-quality-image producing software that is used by many landscape architects. From an amateur to a pro user, there are many tutorials that allow you to create sleek renderings. Indeed, this program is a popular choice to make final renderings and touch-ups. WATCH >>> Sketchup to Photoshop: quick rendering tutorial

10. Adobe InDesign

As part of the Adobe software range, Adobe InDesign has been a true classic, a reliable “go-to” program that commonly used for laying out projects. From booklets to large presentation sheets, we have yet to find something else that achieves the same outcome as elegantly as InDesign. It is also an easy software to learn. WATCH >>> ARCHITECTURE PORTFOLIO TUTORIAL: ADDING TEXT

From the classics to the new ones growing in popularity, we definitely recommend you try out some of these fantastic software programs, if you haven’t already. Sometimes, whilst working in industry, it is just about having knowledge in the right software programs, being able to adapt and jump between them to produce nice drawings at the quickest speed. If you have used some of these options already, do share with us about your experience. Do you have a favorite? What do you use the program for?

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Bayer

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs