The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) recently announced the winners of its annual awards program, honoring the best of the best (at least in the juries’ opinions) in both professional and student work. My guess is the glossy, beautifully photographed images showing built work designed by professionals attract the most attention. But for me, even though I appreciate design eye candy as much as anyone, my focus inevitably shifts to the planning and analysis category and, in particular, the student work, because it is here, in the unrealized work, that we catch a glimpse of where things are headed or, perhaps, should be headed.

The planning award winners include a waterfront makeover for Seattle, a couple of major urban improvement projects in China, a cool proposal for incorporating public art to ameliorate the dreadful monotony of the sprawling corridor through Atlanta, and, most exciting to me, a next step in the planning for the revitalization of the Los Angeles River in LA, which by now seems to have been in the works for forever.

Image: Mia + Lehrer Associates

That project, led by the Los Angeles-based landscape architecture firm, Mia Lehrer + Associates, is another example of how “green urbanism” is catching on in major US cities – a trend that has been amped up by very real examples of the effects of climate change such as “Superstorm” Sandy. More of these types of projects will undoubtedly be seen in this category in the next couple of years, likely coming from recent initiatives such as the Rebuild by Design competition. Time will tell how much of this planning and analysis actually gets translated into built work in the future, but it is fun to look at in the meantime.

Along that same line, since the student awards are even that much further removed from the restraints of reality, they are often more intriguing. With titles such as Dredge City: Sediment Catalysis, Natural Water as Cultural Water / A 30 Year Plan for Wabash River Corridor in Lafayette, Re-transforming Landscape at the Arroyo Seco Confluence, and METABOLIC CHANGE: Coastal Patterns of Human Settlement and Material Flow, it is not too hard to see that broad, environmental, climate-related issues are resonating with students today.

Image: Daniel (Zhicheng) Xu, Purdue

It would be wrong to assume that these (or any) award winners portray the breadth of what is being taught, and should not be interpreted as such. However, these projects do become the standard bearers for quality work being produced by landscape architecture programs – as self-selected by faculty and students, and then as recognized by a jury. The big takeaways for me from the student awards are:

Idealism is alive and well.

Nearly every awarded project conveys the optimistic surety that ecologically responsible design and planning can vastly improve both human and natural conditions. Although most of the human part of that equation is sadly lost amid all of the data and snazzy graphics, I am far more willing to let it slide here than I would be with professional awards. The important thing, as I see it, is that these students are deeply engaged in, and apparently energized by, the realization that there is an unbreakable connection between people and landscape – whether urban, rural, cultural or natural – that can be either for the betterment or detriment of both. Landscape architects, they have learned, can play a critical role in determining which will be the case.

The inevitable problem with this kind of idealism is that it can have a tough time holding its own against the hard force of reality. Students leaving school with ambitions of saving the world can become discouraged by the ho-hum tedium of life as an entry-level grunt. Because of this, teachers and employers should equally shoulder the burden of preparing students for potential disappointment, while allowing them to maintain their ideals, even through the mundane, as they work their way toward making a real difference.

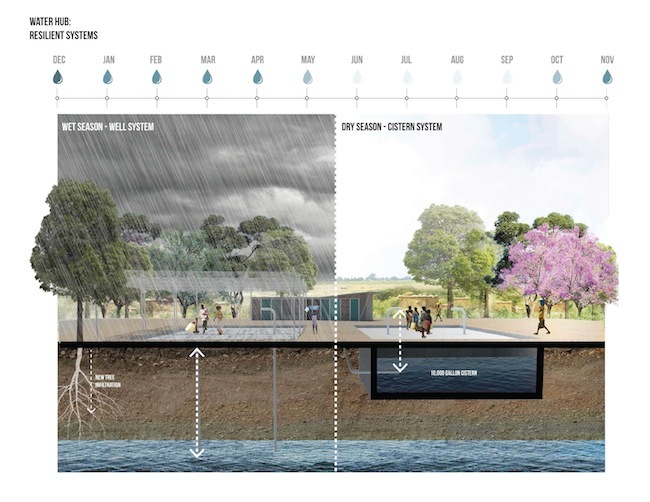

Image: Leonardo Robleto Costante, PENN

Water rules.

With a few exceptions, water is the big focus with the student winners. This is not surprising, really. Landscape architects have been pushing their qualifications as being the best to deal with the ecological, human and aesthetic aspects of water and stormwater management for a long time, lately under the guise of “green infrastructure.” The visceral impacts left behind by Hurricanes Katrina, Ike, and Sandy, along with other types of increasingly intense storms, continuing widespread drought, and sea level rise, have fueled this interest and made water a logical subject of focus. That’s a good thing. The challenge I see, however, comes with making sure the experiential aspect of place-making does not get lost among the detailed complexities inherent in ecology and climatology. I fear this may already be happening on some level, as:

Traditional, design-based landscape architecture has gone AWOL.

Small scale, site-specific design has been nearly impossible to find in the student award winners over the past few years. This does not necessarily mean this work is not getting done, just that it is not considered the most award-worthy. Which is fair. Since much of this work is driven by the research and interests of faculty striving to keep their classes relevant, more cutting edge subject matter naturally takes some priority. Students are obviously being pushed to think critically about contemporary, big picture things, but are they learning how their conceptual solutions might ultimately be implemented? I hope so, since landscape architecture is still a profession rooted in design and construction, and a big part of the value landscape architects bring is their ability to get things built.

Which brings me back to the eye candy. When you compare what wins for student and planning awards versus the built project winners – in this case a cemetery, a section of the High Line, a corporate campus, a waterfront park, residences and a garden, among other projects – it is like night and day. The source of this disconnect is not about any lost sense of idealism; it is about what clients are willing to pay for (and how well it photographs). Until they get built, fantastic and important work, such as Lehrer’s project for the Los Angeles River, remains merely plans on paper.

The fact that something is the right thing to do does not mean it will necessarily get done. That does not mean we stop trying, or stop awarding vision.

Mark Hough Bio:

Mark is the campus landscape architect at Duke University. He has been involved in all aspects of planning and design on the Olmsted Brothers’ designed campus since 2000. Outside of Duke, he writes and lectures on topics such as cities, campuses, the environment and cultural landscapes. He is a frequent contributor to Landscape Architecture Magazine and has written for other publications such as Places Journal, Chronicle of Higher Education, and College Planning and Management, along with a regular blog post for the urban design website Planetizen. In 2011, Mark was awarded the Bradford Williams Medal, for recognition of excellence in writing about landscape. Contact him at Twitter: @mharrisonhough.

This article first appeared in Planetizen. All images via ASLA Awards, lead image by Matthew Moffit, PSU.