“I find that pulling out pens, pencils, and tracing paper and sketching, especially in meetings, changes the mood and the design experience for others in the room in a very noticeable way. The sound of a pencil swishing across the paper, the movements of the arms, people watching something interesting being made with the simplest of tools – it injects fun into the atmosphere, and credibility for the person holding the pencil.”

Richard, I’d like to begin this interview with the 25 year-old question: Do hand-drawing skills have any relevance in the landscape design office of the 21st century?

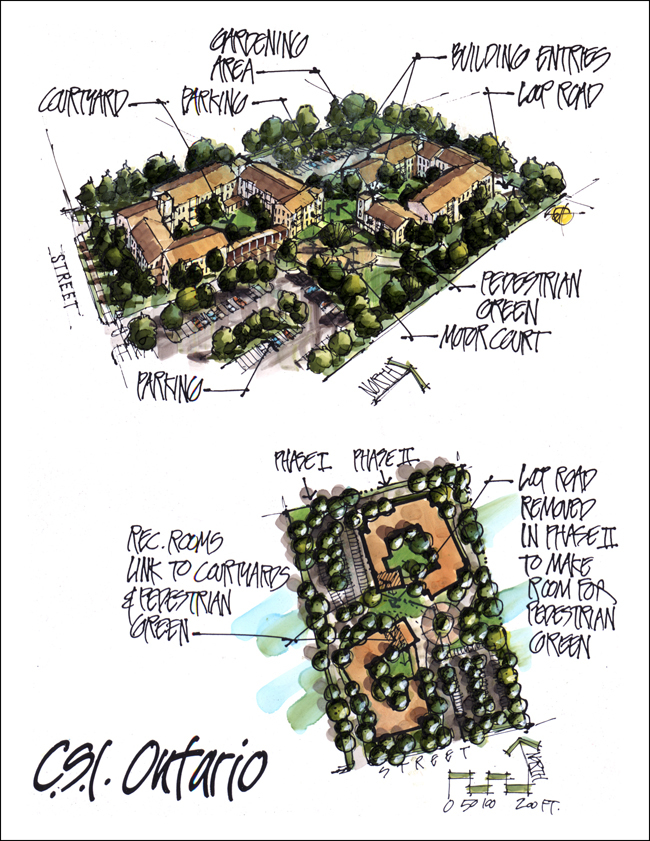

Yes, for specific reasons. The first reason is production. There are times in the design process, especially early on, when a sketch is hands down the quickest way to develop or present an idea.

The second reason is how a client relates to a sketch or hand rendering. These kinds of graphics express artistry, and they inject fun into the design process. We can overlook how important this is. A client’s perception of value is to a large degree based on emotion. In my experience, hand sketches and renderings elicit a different kind of emotional response from a client, as compared to a computer rendering. Their eyes light up in a different way. There’s more interest, more enthusiasm.

The third reason is credibility. When we sketch, we stand out artistically from those who rely on computers to express their ideas. I’ve seen this play out in many meetings. When a designer can draw, that designer is perceived differently. It’s assumed, even if only subconsciously, that he or she must also have good design skills. Of course this may or may not be true, but it’s the first impression that I’m talking about here. And that impression is key.

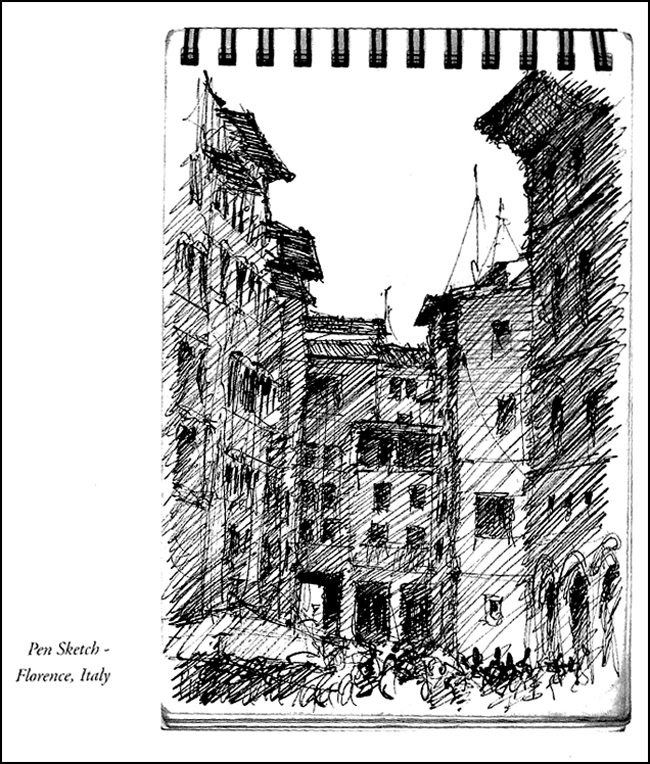

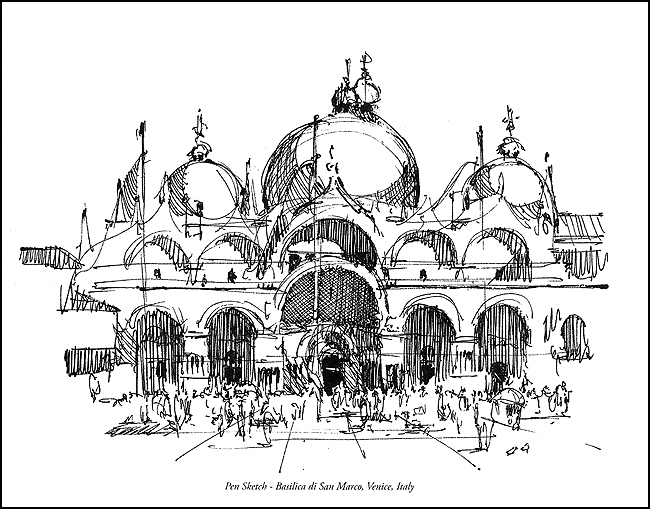

The fourth reason, and I believe this to be the most important reason that drawing will continue to be relevant, is it directly develops our own abilities to see and think. Personally, I’ve gained more from observational sketching, sketching from life, than any other activity. It was by doing this kind of sketching that I developed an acute sensitivity to composition, shape, gesture, tonal value, and texture–a sensitivity that helps me to be a better designer. Although it gets little attention in school and in many offices, I’ve found it to be one of the most valuable habits that a designer can adopt. I’m sure that we’ll get into this more during the interview.

So you’re optimistic about its continued necessity and importance?

Absolutely. There are plenty of clients today that value and desire artistry as part of what we do as landscape architects. And there will be offices that serve that clientele with a service that is more personal and artistic. When every firm uses the same software and delivers a product that looks more or less the same, from the clients’ perspective, the main difference comes down to who can do the work for the least price. Instead, I’d rather be focusing on how we can stand out.

How does the ability to quickly sketch out ideas affect the design process?

It gets the designer thinking about how a space will look and feel in three dimensions. It also impacts how others experience and participate in the design process.

First, when we design solely in plan-view, our tendencies are to produce a design that looks interesting from how we’re currently looking at it – from above. But, this doesn’t necessarily translate to a good three dimensional design. I was lucky enough to learn this lesson right out of school. A Landscape Architect mentor shared with me some photographs of a built landscape that he had designed that looked absolutely exquisite. He then showed me what that same design looked like as a site plan–it looked like nothing! I learned that plans and three dimensional spaces were two very different things. From that day forward, I sketched in 3D throughout the design process.

Also, I find that pulling out pens, pencils, and tracing paper and sketching, especially in meetings, changes the mood, the design experience, for others in the room in a very noticeable way. The sound of a pencil swishing across the paper, the movements of the arms, people watching something interesting being made with the simplest of tools – it injects fun into the atmosphere (and credibility for the person holding the pencil). Drawing invites participation in a very different way than when a group is looking at a 3D computer model on a screen. Freehand sketches don’t look polished or complete. They’re rough thoughts, suggestions, on paper. These kinds of drawings remind everyone in the room that we’re making something together. Using simple tools to make the sketches reinforces this point.

As a side note, I’ve come to appreciate the fun of these experiences. The joy of making something. The craft of it. When I was younger, I was laser-focused on the end product–the submittal, the approval, the built project. I now lose myself in each moment of the creative process. These creative experiences are what attracted me to a career in the arts in the first place.

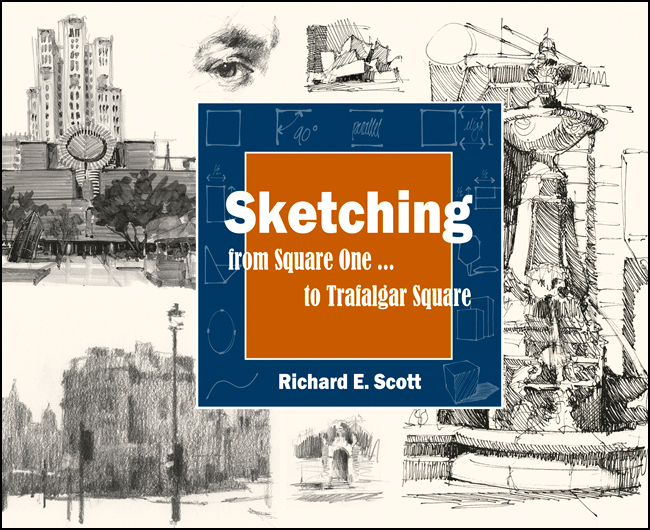

In your book Sketching: from Square One to Trafalgar Square, there is a chapter entitled Emotional Response, where you speak of a “compelling motive”. In this chapter there is a discussion about the emotion, reaction, and editing process involved in deciding on the content of a drawing. How does this exercise of self-examination while sketching help one to become a more informed designer in general, and a more informed landscape designer in particular?

You learn how to connect more personally with a subject matter, and how to evaluate what is most meaningful in that subject matter. By going through this kind of self-examination process, we develop our own personal opinion on a subject or a project.

It’s this opinion that guides every decision, every action. Based on our own opinion, we emphasize those things that we believe matter most, we deemphasize those things that we believe matter less, and we remove those things that we believe are irrelevant. When we sketch, we gain direct experience with this kind of self-examination process. We develop thinking skills, not just drawing skills. And it’s our thinking skills that are of value to a client or employer.

In the book, you passionately encourage travel as a way of immersing oneself in the act of being completely present in a particular place and time. Can you tell us more about that and how that quality of awareness relates to the act of sketching?

Your sketchbook is a record of what you notice. What you notice depends on your level of awareness. Sketching is an effective and fun way to sharpen your awareness. The better your awareness, the more sensitive a designer you will be.This kind of awareness is not accessed by simply looking around you with your eyes wide open. It requires that you actively participate in the experience. It’s in the process of sketching your environment that subtle qualities slowly reveal themselves to you. You become a better seer.

Just as playing a musical instrument will sharpen your ear for music and sound, sketching your environment will sharpen your ability to recognize compelling compositions, shapes, tonal values, and textures. There’s no question that a concert violinist experiences sound and music in a very different way from me, which is to say that she hears things that I don’t. Think about that. She hears things that I don’t, even though we’re in the same room. The same is true for how we see the world around us. When you sketch, you will see and notice things that you didn’t see before. Sketch each day for fifteen minutes, and in six months you’ll be impressed by how differently you see the world. This change can and should impact how you design and solve problems. But, even if it didn’t, it would still be worth your time because you would notice more – your moment to moment experience would be richer. What could be more important than that?

Last thing, although travel is important in broadening one’s perspective, and therefore choices, it’s not necessary to travel to gain access to a higher level of awareness. Simply open a sketchbook and immerse yourself in the place and moment you’re in right now.

How is your sketching style reflected in your landscape design philosophy? In other words, does your particular design philosophy relate in a conscious way to your sketching style or vice-versa?

Sketching has improved my awareness and appreciation of composition. And I’ve found that composition is one of the most difficult things to learn or teach in the arts. I’m not sure it can really be taught at all. But it can be picked up through experience. It’s through direct experiences, like sketching, that one develops a sensitivity to it.

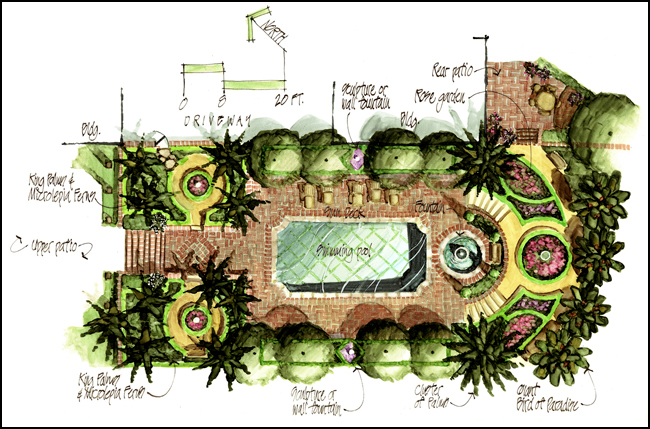

My own sensitivity to composition impacts how I design landscapes. I look at every object, a tree, a terrace, a building wall, a doorway, a furnishing, and so on, as an abstract shape. Each shape that is introduced into the design must harmonize with the exiting shapes (the larger context). By this I mean that the “new” shape should be placed and configured in such a way that it makes the surrounding, existing shapes look better. It’s my opinion that most options will not make the overall composition better, but worse. My job as a designer is to find those relatively few options that improve the look and function of the whole.

When one does a good job with this, the new shapes harmonize so well with the existing shapes, that it’s hard to imagine it any other way. And when it’s built, it looks like it’s always been there.

Have you “always” been able to draw well?

I’ve had the impulse to want to draw since I was a child. Because of that impulse, I practiced a lot. Any ‘talent’ that people felt I had was simply a result of practice. I think that anyone reading this interview likely shares that impulse, even if they haven’t yet acted on it. When it comes to drawing, effort matters more than talent. It boils down to committing a portion of each day to sketching. Fifteen minutes each day, no matter what, is a great target to start with. The reader can find additional tips on my sketching website.

In the conclusion of Sketching: from Square One to Trafalgar Square, you describe the sketching experience in terms often used to describe the practice of meditation. What do you see as some of their more important commonalities?

Raising your awareness and, as a result, having a richer experience of day to day life can be experienced through both practices. Being less judgmental is another experience that can be learned through both. In sketching this means being aware when your mind criticizes your own work—a common experience when you’re learning, or are a perfectionist. In my book, I discuss how to shift your attention from what you see on the pages of your sketchbook to what is happening inside your own mind. This approach is critical to getting the most out of the experience, and generating the enthusiasm to keep at it.

In answering your question though, what really comes to mind is the inability of words to really describe either experience, and what can be gained by doing them. Awareness, seeing, and sketching are all words that seem easy to grasp, but these words really don’t connect with what the actual experiences feel like. The journey is very different from the map.

Experiencing them is the only way to learn or understand them. In adding these habits to our lives, we find that the greatest benefit, the greatest reward, is not in anything we produce, per se. It’s the subjective experience we carry around in our heads from moment to moment. Through practices such as meditation and sketching, life becomes richer, and we feel a deeper connection to the world that we’re a part of.

Can you tell us about that first job where your drawing skills were instrumental in helping you land the gig, and also how your story might be applied to today’s job seekers?

I got my first job in landscape architecture solely because I could draw. I was a year out of high school and was lucky enough to see a wanted ad in the local paper. I didn’t even know what landscape architects did. I showed them my drawings and was hired. I think I made six or seven dollars an hour at the beginning, and was thrilled to be making money for the first time by drawing. I was in heaven. After a few days on the job, I knew I’d found what I wanted to do for a living. I’ll forever be indebted to them for that first opportunity in the profession.

Drawing continues to be a sought-after skill today, even though it’s rarer than it used to be. And I think that employers who are designers at heart will always appreciate a person who has a love for drawing. I say this because the sensitivity, the creativity, and craftsmanship that one gains through drawing can very much benefit an office. I have a landscape architect friend who recently told me a story about some interviews that he conducted with students for an internship opportunity. The first one who pulled out a pencil in the interview got the job.

Since 2008, how has your business strategy evolved in order for you to stay afloat in the landscape profession?

My strategy is in offering a range of different services, and being continually mindful of why I’m hired to deliver those services.

As a landscape architect, I feel that the advantage I bring to a project is my ability to see (learned through sketching), and a willingness to listen (and ask many questions). To my mind, it comes down to applying those two skills again and again to better serve a client. I never forget that.

As an architectural illustrator, I feel the reason I gain work is my enthusiasm with working with other designers, and my love for producing compelling imagery. I do everything from quick concept sketches, to illustrative plans, to refined watercolor renderings. Wearing these different hats, designer and illustrator, means that each week is different, which I like. They also inform and enrich one another.

I also teach workshops, produce artwork, and sell books. All of these activities produces different streams of revenue, and all have a common theme: to add beauty to the world, and to help others do the same. Each morning, I wake up enthused by what I get to do each day, and appreciate what a privilege it is to make a living in the arts.

As a longtime educator, you’ve inspired countless design students to draw. Are there particular designers or artists whose drawings inspire you?

For years I’ve drawn inspiration from Lawrence Halprin, Roberto Burle Marx, and Laurie Olin, because they were landscape architects that successfully applied sketching and art to their design processes.

I also look to animation for inspiration. Each time Disney or Pixar produces an animated feature, they also release a book about the process of making the film, usually called “The Art of fill in the movie title.” You can’t believe how much usable information can be found in these books, and applied to what we do. And it’s inspiring to see how artists and designers at cutting edge companies like Pixar continue to freehand sketch today to design and develop scenes and characters.

As for artists, John Singer Sargent has made the biggest impact on my illustration and artwork. There’s a new book on him called “John Singer Sargent Watercolors.” A great go-to source for daily inspiration.

So in closing Richard, is there a particular up-coming project, or something “on the boards” that you would care to share with us?

I’m working on some designs for estates right now in Bel Air, Malibu, and Montecito. I enjoy this kind of work because I get to be involved in every aspect of the design and building process…from concept sketches to grading and drainage, to construction details. Back at the studio, I’m doing some watercolor renderings for architects and landscape architects that I work with. I also have a graphics workshop in the planning stages at UNLV, and I’m planning some graphics workshops later this year in Pasadena.

Richard E. Scott is a licensed landscape architect, architectural illustrator, watercolorist, and teacher.

Richard E. Scott’s new book, “Sketching: from Square One to Trafalgar Square” can be purchased at www.sketchingfromsquareone.com or amazon. You can learn about his graphics workshops at www.graphicsteacher.com. To contact Richard about conducting a workshop at your office or school, or to inquire about hiring Richard to produce sketches or renderings for your office, he can be reached at richard@graphicsteacher.com.

All images courtesy Richard E. Scott.

Lead photo of Richard by William Wray.

Thanks to Kim Rhoads for #s 7 & 8.

Published in Blog

Brandon Reed, CVO, ASLA / Rooftop and Urban Designer / Landscape Architect

Richard Scott is the real deal! I know him both professionally and personally and I can attest to his great character as a person, artist, and educator. I have taken every one of his graphic workshops and he has been a huge inspiration and influence on my graphic presentation and ability! I own his new book and its on my list of most influential sketch books for our profession and sketching in general….You won’t find a more talented professional and person anywhere.

Mitch Howard

Brandon – Well put. I was just working on a concise description of Richard’s personal sincerity and passion for his work, and you nailed it. The Real Deal. Thanks.