In one of my previous posts, I took a look at the promise of Vectorworks software for landscape architecture. I was impressed by the host of features the software has to offer through its multiple platforms: basic 2D/3D modeling with Fundamentals, landscape-specific tools with Landmark, and slick output with Renderworks. On top of these, the software utilizes a BIM approach to improve understanding of design decisions and coordination with related professionals in order to better steer final outcomes. It is aiming to place tools in the hands of landscape architects to design and interact on the same level as our architect counterparts. I have spent a fair number of hours learning Vectorworks and getting used to how it handles in order to assess how well the software delivers. The article contains a large amount of information, so to view a particular topic use the navigational structure below.

Basic Modeling – File structure | 3D Considerations | File Sharing

BIM Functionality – Implementation | Grading | Smart Objects | Planting | Irrigation | Drainage | Worksheets

Output – Construction Documentation | Rendering

What’s New to Vectorworks 2017

A well developed model can quickly be utilized to create plans, construction details, and photo-realistic renderings. Image credit: Nicholas Buesking

The first essential aspect of the program is 2D drafting and 3D modeling. Vectorworks behaves like a mashup of Rhinoceros and Sketchup. Vectorworks is tool-based like SketchUp rather than command-based like AutoCAD or Rhino. The available tools provide simple geometry creation for efficient drafting, yet there are a host of tools that enable highly complex and accurate shapes. Objects are each assigned a layer and a class. “Classes” act like AutoCAD’s layers while “layers” are a meta-structure that help separate overlapping aspects of the design, such as hardscape, site grading, and planting. The dual system allows for powerful control of visibility in a 3-dimensional model; however, establishing and following a strict layer/class protocol is essential because without management the file can become cluttered, requiring tedious post hoc correction. One Vectorworks user related that designers in his office dislike working in their coworkers’ files because each handles the layer/class system differently. This is not a problem with Vectorworks itself, but an issue inherent in any drafting program, amplified by the dual system. In its favor, Vectorworks attempts to help manage the issue by auto-classing a number of objects, such as dimensions or plug-in object components.

The program handles 3D space fluidly, if not always intuitively. Each layer is assigned an elevation on which objects are placed as default but can be moved. Locations of objects on the Z axis are stored in relation to the layer elevation, which can lead to confusing jumps in geometry when changing an object to a different layer. Vectorworks employs a clever use of “working planes” to override default elevations and constrain geometry creation intuitively. For example, in a top or side view Vectorworks drafts only on the visible plane based on a snapped starting point. Additionally, the program has zoom and x-ray functions to provide greater precision when acquiring snap points. Together, these eliminate many of the frustrations in other 3D modeling programs caused by the time consuming process of selecting the correct snap point by navigating the model. On the other hand, objects buried below others can become extremely difficult to select, especially when they align with another object. Vectorworks supplies no easy way to select overlapping objects through an object selection window, like the ones found in AutoCAD and Rhino. Likewise, Vectorworks does not have a typical isolation mode, though you can control the view and editability of non-active layers and classes. These settings can be preserved in a “saved view” for quick toggling between commonly needed layer/class settings. The ability to isolate several classes quickly to perform specific tasks and then restore the previous visibility state would be a nice feature but Vectorworks’ other visibility features limit the need.

A strength of Vectorworks’ modeling interface is that there are frequently multiple ways to create objects based on a user’s natural workflow. For example, hardscape objects can be created via drawing the geometry directly with the Hardscape Tool or converted from an existing polygon drawn during the concept phase. Unfortunately, the result is a large number of tools that are not always in intuitive locations. In fact, one of my biggest frustrations as I learned to use Vectorworks was the number of tool choices and their configuration. Important options can be buried within contextual tool palettes or hidden in tool settings. The information embedded into each object and different tool options can make troubleshooting difficult.

Vectorworks allows for project files to be shared easily with other offices and disciplines. It can be exported to a DWG or DXF file for coordination with civil engineers or architects, and Vectorworks 2017 can now import files directly from a Revit format. Feedback that I have heard from users has been that the process is painless as long as the workflow is coordinated. In the case of an engineer, it generally means drafting from the coordinate system the engineer is using so that the model will import into the expected place and not require shifting upon receipt.

Overall, once you understand the interface, have a good file management protocol, and have the right resources at your fingertips, modeling becomes a smooth process. The basic drafting tools, however, are by no means what makes Vectorworks stand out. Rather, it is its impressive array of ever-growing BIM tools geared towards landscape architecture.

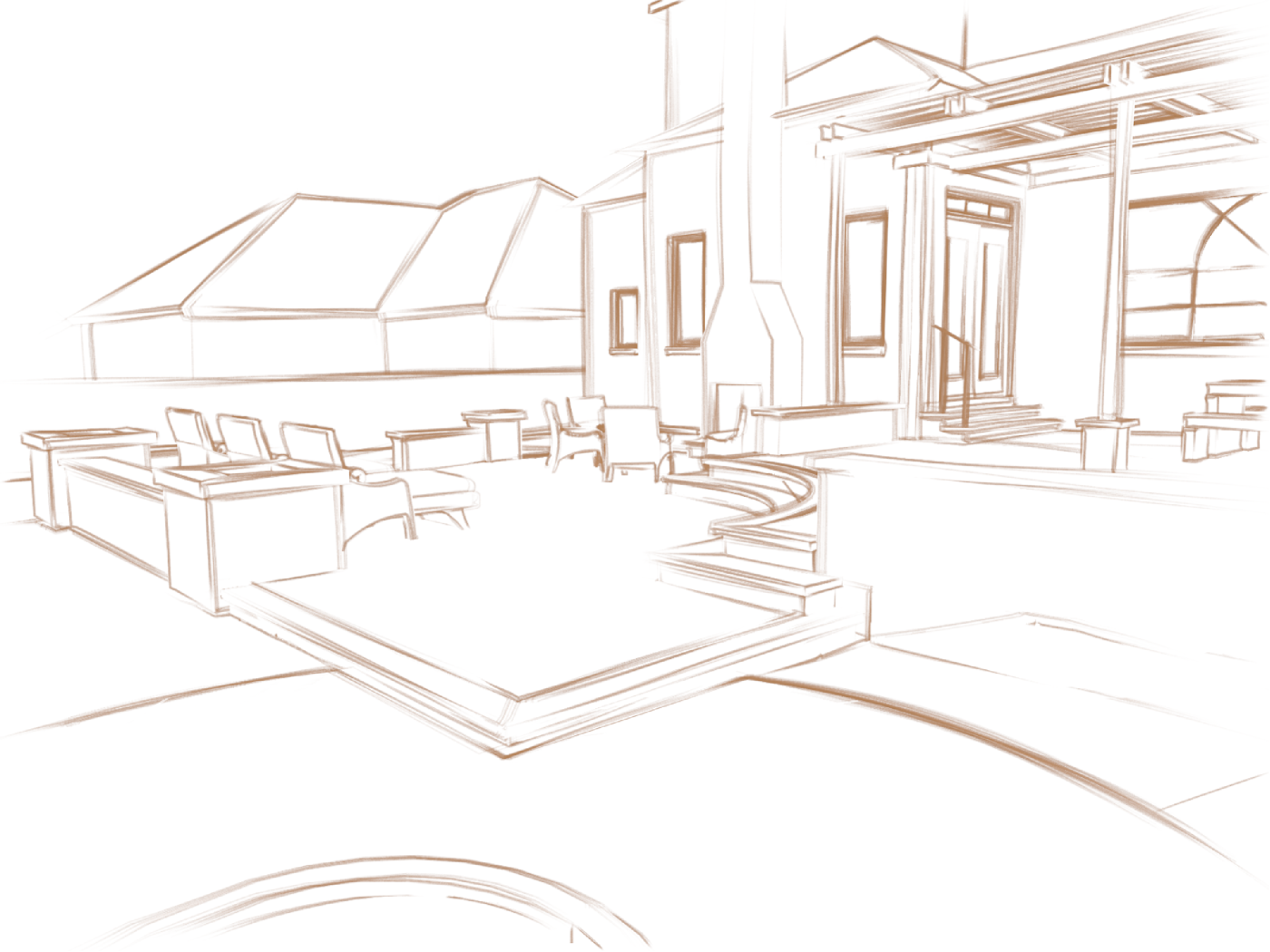

Sketch style renderings are great for conceptual-level presentations, giving the client a vision of the proposed design without being too detailed or too regimented. Image credit: Nicholas Buesking

Working in a 3D workspace with BIM data means resource investment. At initial implementation, creation of a company-wide database of drawing templates and resources libraries, which include plant objects, textures, render styles, and other symbols is imperative. While it may sound daunting, a number of practitioners with whom I have spoken indicated that, between Vectorworks’ existing resources and the ease of implementing new custom resources, adopting Vectorworks did not cause a major disruption in the company’s production. Additionally, more resource investment is required to establish an existing model at the start of each project; however, between a rich resource library and Vectorworks’ BIM capabilities, projects can be run more efficiently with greater control over design goals and product.

One of the most essential aspects of Vectorworks’ BIM functionality is its grading tools. Through a series of elevational source data inputs, Vectorworks constructs an existing digital terrain model (DTM) complete with interpolated contours, labels, and flow arrows. Generating the existing terrain data is easy. Three dimensional points or contours from a survey can be imported into Vectorworks from a host of file formats, or the data can be entered manually from field notes. During the design process, parametric site modifiers can be inserted and classified as “proposed” to affect the DTM. The modifier tools Vectorworks offers provides functionality that reflects the needs of designing a site. Contours provide the most standard approach but are nonetheless effective. Pads are extremely useful for creating sloped or non-sloped planar surfaces and is also integrated into the Hardscape Tool. There is an option to create retaining edges around pads for terraces and walls. Most of these tools function smoothly, but a few are cumbersome, requiring important data to be set only after object creation through the use of drop down menus and input fields.

Due to the nature of inputs the DTM receives and the need to interpolate, proposed grading plans can initially lack smoothness, with contours taking on a disjointed appearance. This may be an issue with the underlying calculation metric of the program, but I suspect much of it is a factor of the specific modifier inputs to which the DTM must respond. As a result, the grading plan may need refinement in order to deliver the level of artistry landscape architects desire. At the moment, Vectorworks does not provide an organic site modeling tool, such as SketchUp’s plugin sandbox, for such refinement. The Vectorworks team has confirmed that they are working to develop a more fluid process of interactive terrain modeling at the wish of Vectorworks users. We should expect to see that wish granted soon. For now, utilizing the contour tool to overwrite and smooth the auto-generated proposed contours is the best method. Because the site model is a part of the BIM workflow, it tracks both existing and proposed conditions, which allows for a real-time understanding of cut and fill needs. Bryan Goff, director of Design + Sciences for Grey Leaf Design, Inc. and long-time Vectorworks user, said that his company used Vectorworks’ cut/fill capabilities on a large residential project in Minnesota to move over 7,000 cubic yards of soil successfully on site without hauling away or importing any soil.

To complement the site model, Vectorworks has a host of smart objects. Smart objects contain information and editability far beyond the standard object in Vectorworks. The foremost is the Hardscape Tool. From it, surfaces such as patios, walkways, and gravel pads can be created. Some users even use it for sod. They can be given styles to detail base, leveling course, and pavements. Oddly, however, the styles are difficult to find and edit, and they are not integrated with other hardscape settings such as rendering options. Hardscape textures can be problematic too, conflicting with the site model if the hardscape object is used as a site modifier unless another smart object is generated to control appearance. Both these issues are advanced use of the software, but they fall within the workflow of effective BIM process and output. Another common tool is walls. They can be assigned particular assemblies, which is useful for landscape walls, building walls, and even foundations. Walls can also be stepped at the top and bottom to accommodate changes in grade. Unfortunately, horizontal-based objects such as coping and foundations cannot currently be combined with the main wall. They must be created as separate objects. Similarly, the stair tool provides a large range of functionality and control over stair objects, but there are limitations. The tool cannot support one to two riser steps nor can it create curved/L-shaped steps. In these cases, non-smart objects must be created.

Because plant objects have a 2D and 3D component to them, all that is required to move the 2D planting plan into a 3D representation is switching into a perspective view. Masses of plants can be given a more natural look with an automatic rotation option, which was not implemented in this rendering. Image credit: Nicholas Buesking

Another important category is the planting tools. Planting tools are the most common set of landscape tools found in other software packages. Vectorworks’ planting tools perform like a well-oiled machine. They allow you to place singular plants, rows, clusters, or groups of plants. One tool creates landscape areas that can contain multiple species, useful for specifying seeding mixes. Placed plants are automatically sent to the surface of the DTM. All of the parameters used when placing plants are stored and can be modified after creation so changes in design require only quick adjustments rather than laborious re-drawing. Once in the model, plants can be replaced either individually or as an entire species. Existing trees can be placed with embedded data such as species, size, label, current condition, and removal/protection instructions. Auto-generated classes in the plant symbols such as fill, bloom color, interior linework, and outline provide a high level of control over the 2D display of the plants. Tags for the plants are automatically generated and can be easily organized through a specialized distribution tool. The plant schedule can be generated with a single click. Every plant object has a 2D shape, a 3D visualization, and source data associated with it. Vectorworks comes with a pre-packaged set of 168 configured species-specific plant symbols and even more generic symbols. Vectorworks also has an extensive database from which to draw information during new plant object creation, which simplifies the process of creating a fully-developed plant object. Once developed, an office’s library of plants will remain relatively stable, with only periodic updating required.

With Vectorworks 2017, the company is showcasing its commitment to upgrading the landscape aspect of its BIM functionality. It is premiering an irrigation toolset within the Landmark module. Its capabilities include zone planning, water budgeting, hardware and pipe placement, coverage mapping, and flow calculations. Vectorworks worked closely with many of the industry-standard manufacturers to provide real specs on hardware. Bryan Goff raved about these new tools, saying, “Irrigation tools in Vectorworks 2017 offer the easiest, fastest, most accurate system I have worked with, giving us a MASSIVE competitive advantage in the market.” I do not doubt these tools will require refinement, but they promise to be a boon to anyone who deals with irrigation design due to their integration into the BIM workflow.

The new irrigation component of Landmark is an exciting addition to the landscape BIM toolset of Vectorworks.

One key functionality that is notably missing from Vectorworks is drainage design as it is a huge aspect of landscape architecture. Resources for specific hardware such as catchment basins are available, but Vectorworks does not have specific tools to deal with drain tile layout and design. The Vectorworks team has indicated that its users have not yet indicated a strong desire for such a module. As a result, drainage design must be adapted to a low level of BIM functionality, with simple objects representing drainage structures. Alternatively, a few plug-in products exist to address civil-oriented needs, including sewer and water lines.

The key of BIM is to use the data residing in the model to create a deeper, more accurate understanding of the design. Vectorworks uses worksheets to organize, analyze, and visualize the information collected within the model. They are spreadsheets that operate similar to Excel documents, but they have the advantage of linking to data directly in the model rather than need manual input. A worksheet can be saved and later imported into another document for instant use. Some standard applications of worksheets are plant schedules, cost estimates, ordinance requirements, watershed analysis, and cut/fill calculations. Though I have only cursorily used worksheets, other Vectorworks users have stressed that they work extremely well and can be as complicated or simple as desired. One commented that the only limitation to them seems to be the user’s own imagination. My biggest concern with worksheets is that in some cases, such as green space tabulation or watershed analysis, the creation of additional objects not constrained to the rest of the design model is required. If changes are made to the design, these objects must likewise be altered in order to keep the worksheet output accurate. In the end, it comes down to user responsibility for ensuring all aspects of the model are updated. Notably, this process is still more efficient than manual recalculation.

The layer/class system with auto-classing allows for great control over model visibility, allowing conceptual plans to construction documents to reside in the same drawing without becoming impossible to navigate. Image credit: Nicholas Buesking

Sophisticated modeling and intelligent data handling is all well and good, but being able to deliver a crisp finished product is an essential aspect of the software. There are two areas of output on which I want to focus: design documentation and rendering.

When it comes to producing construction documents, I have mixed feelings about Vectorworks’ interface. Drawing sheets are treated as part of the layer system. The system works sensibly with all of the objects on a sheet being drawn on that sheet’s dedicated layer, though class differentiation is still allowed. Each sheet is named (i.e. LS-1) and titled (i.e. Planting Plan) and can be based on a template, allowing users to import a saved title block. The document has overall information that can be updated on any sheet and pushed through to other title blocks, and each title block has information tied to the specifics of the sheet itself. Vectorworks also has an Issue Manager tool to manage sheet numbers, record data, titles, and issue notes through a single dialog for the entire sheet set. One fantastic thing that Vectorworks does is to link some labels to information in the document. For example, detail callouts and section cuts can be linked to viewports (drawings) in the file. It the title or sheet number of the viewport changes, so does the callout. Annotations like drawing titles and dimensions can be grouped with the viewport. It is useful for maintaining the integrity of a single drawing, but it restricts the ability to align elements between drawings efficiently. You can also edit the model from a viewport. Unlike AutoCAD, you never need to worry about disturbing the view since scale and pan/crop are set separately. Finally, I found that annotation styles, with the exception of dimension standards, can be difficult to control because the current style is not always immediately apparent. While it has some great features, to me Vectorworks’ documentation system was its least exciting element.

Night rendering using Renderworks. Fire image texture has a “glow” reflection to produce the low level lighting shown. It is the same option that must be manually turned off to achieve correct lighting of plant objects. Image credit: Nicholas Buesking

Vectorworks has a specific platform, Renderworks, for handling 3D rendering. It is a powerful engine that delivers comparable results to other heavy-hitting industry standards like V-Ray and Lumion. It comes fully integrated into the Vectorworks package, so textures and appearances can be developed throughout the modeling process. The range of lighting, camera, texture, and other detailed options give a high degree of control over the final rendered outcome whether indoor or outdoor. Navigating available textures and selecting appropriate ones can be tricky, as the resource browser can get cluttered with a large number of files especially plant objects, and drop down menus for class and render options display only text. The new Resource Manager introduced in 2017 should alleviate these problems since it includes greater control over file structure and provides a search function. The biggest issue I found with rendering landscapes in Vectorworks is that pre-developed plant objects generally provide their own light. It makes daytime renderings more vibrant but is problematic for nighttime renderings. The “glow” setting can be turned off, but it is not feasible to toggle these settings between scenes. Renderworks does not support animations, so if such a product is desired it does require exporting to another program like Cinema 4D or Lumion.

Another feature of Renderworks is that it hosts a package of modifiable “artistic” styles. These stylizations mainly render linework and color fills and are especially good for conceptual images. They can elevate a drawing past a stiff CAD drawing and give it the quality of a hand-sketched illustration. It is a good way to provide visualizations without needing to fully develop a model for photo-realistic renders. Overall, Renderworks performs excellently in its versatile range of capabilities.

Vectorworks 2017 was just released mid-September. Here’s a brief overview of some of its new features and improvements:

- Irrigation Tools – See the above section and video

- Railing and Fence Tool – A significant upgrade to a high functioning BIM tool that allows the customization of railing profiles, post placement, and other fencing and railing details.

- Updated Planting Tools – Improvements include multi-depth hedges and landscape area upgrades

- Resource Manager – A major overhaul of the previous “resource browser” which integrates resources on local drives, network drives, and online sources in an organizable, searchable interface.

- Web View and Virtual Reality – Models can now be viewed with portable or desktop devices for a first-person perspective of designs without any need for additional software

- A host of other new features and improvements

Watch the short video on the VR viewing feature Vectorworks now offers. It’s an awesome way to help clients understand the design!

One of the things that has impressed me most about Vectorworks is that the company is constantly improving old tools and creating new ones. Stephen Schrader, associate landscape architect at Holcombe Norton Partners, Inc., says that he has seen Vectorworks’ BIM landscape tools improve greatly in functionality since the time he first started using the software. I have also continually heard from the entire Vectorworks team—engineers and executives alike—that they are constantly focusing on what the users want and need to improve their workflow. Though I have my critiques, Vectorworks’ BIM tools perform well, and the program is conducive to creating a streamlined set of products, from conceptual design through to documentation. As such, Vectorworks delivers on its promise to provide landscape architects with relevant BIM tools. Due to the company’s value of constant improvement, I have confidence that the tools it provides for landscape architects will only advance in the years to come.

Lead image credit: Vectorworks, Inc.

Published in Blog