Author: Jolma Architects

How Landscape Architecture and Urban Design Can Reduce Crime

Crime is a perennial problem facing many inner-city areas. Antisocial behaviour and crime are major factors affecting urban decay, property prices, and quality of life. In this article, we investigate how landscape architecture and urban design can mitigate, reduce, and control crime in the urban environment.

Crime vs antisocial behaviour

Crime can relatively easily be defined as acts contrary to the governing law of that area. For example, the same act of recreational smoking of marijuana is legal in the US state of Massachusetts but is currently illegal in the state of New Jersey. Antisocial behaviour, on the other hand, is less easily defined. The Home Office in the UK recognises that the definition of anti-social behaviour is influenced by context, location, community tolerance, and quality of life expectations. The UK government has adopted the following definition: ‘Acting in a manner that caused or was likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress to one or more persons, not of the same household as (the defendant).’ (Crime and Disorder Act 1998). Therefore, antisocial behaviour can range from the somewhat innocuous acts of ‘loitering’ or ‘hanging around’ through littering and vandalism, right up to intimidation, sexual harassment and violent crime.

The problem

While public open space is recognised as having positive impacts on local residents, research by CABE Space indicates that community groups estimate that 31% of parks suffer from unacceptably high levels of vandalism and behaviour related problems.

ASLA 2016 General Design Award of Excellence. Underpass Park, Toronto, ON, Canada / PFS Studio with The Planning Partnership – bottom-left images PFS Studio right image Tom Arban

Inclusive and safe

Antisocial behaviour can particularly affect women and children. For example, the Guardian reports that 43% of women aged between 18 and 34 had experienced sexual harassment in public spaces. We know that when we design spaces to be welcoming to women and girls, then those spaces will be occupied by more people in general. The UN has published guidelines for creating spaces that are safe for women and girls. Key points include:

- Easy access to and from the location

- Easy movement within the location

- Good lighting

- Easy-to-read signs

- General visibility of the entire space, free from hiding places

- Includes mixed

- Provisions for different seasons

- Provisions for young children and the elderly (because women are often carers)

- Access to clean, secure, easily accessible toilet facilities

The process of creating safe spaces for people who identify as female results in spaces that are safe for all. The guidelines from the UN are very similar to those proposed in the Safer Design Guidelines for Victoria, in Australia. These guidelines emphasise the importance of good visibility and visual connection.

Bad solutions for preventing crime in the city

Visibility is a key factor for designing out crime. A study by the College of Policing notes that while Closed-circuit television (CCTV) has been proven to reduce premeditated crime, there is no discernible effect on spontaneous antisocial behaviour and opportunistic crime. CABE Space raises concerns that ‘adopting …CCTV and …without considering the overall design and care of public space will result in the creation of ugly, oppressive environments that can foster greater social problems.’ So, adopting CCTV as a cost-effective means of controlling behaviour can encourage poorly designed spaces, without necessarily mediating violent and opportunistic crime.

Green Man Lane (before and after) by Conran and Partners. Left Jim Stephenson, clickclickjim, Right JZA Photography

Better solutions for preventing crime in public open spaces

A good way to decrease crime and antisocial behaviour is to increase visibility. One of the best methods to do this is through natural or informal surveillance. Natural surveillance refers to the concept of increasing visibility between places and user groups.

For example, a damming 2007 report into the Green Man Lane area of West Ealing in London pointed to problems either exacerbated or caused by the architecture of the area. The local authority took a proactive approach. Architects Conran and Partners used the principles of ‘‘Secured by Design’ to design out the multiple escape routes, aerial walkways, and open access undercrofts that disconnected users from each other and replaced them with more traditional streets that have greater natural surveillance from passing traffic, other pedestrians, and homes that front the street. Research shows that homes designed to the Secured by Design principles have a 50% lower risk of burglary, while car crime can drop by 25%.

Green Man Lane by Conran & Partners ; copyright Rydon

Spaces that are designed for people to spend time in should be defensible (i.e. seating areas should have good visibility so that the users feel they can see potential threats coming). They should also be sheltered enough so that they do not feel danger can sneak up on them. Nodal spaces that are designed with prospect refuge in mind are generally more attractive to users.

Good access and circulation at all levels increase safety. A study has shown how projects like The 606 in Chicago, which includes an elevated greenway, can reduce crime in adjacent neighbourhoods. The New York Times notes that The Highline also experiences lower than average crime. Access should be legible and easy to follow without the need for signage. It should also include multiple routes to give users choice and make it harder for criminals to predict potential victims’ movements.

The High Line_Diller Scofidio + Renfro

The 24-hour economy reducing night time crime

Urban designers can not only boost the economy by creating cities that are used around the clock, but can also reduce night time crime at the same time. Since 2012, violent crime in Sydney has been reduced through focusing on the night time economy. Increasing the diverse mix of functions, such as cafes, 24-hour gyms, and shops, increase pedestrian movement and natural surveillance.

Strategic change to challenge antisocial behaviour and crime

These principles are now being adopted at a strategic level. The City of Los Angeles has invested $25,000 in publishing ‘Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design’ (CPTED) guidelines and training staff in how to assist developers and built environment professionals design better environments that discourage crime. The programme aims to ensure all residents are safe, whether they live in luxury apartments or affordable housing.

Prague evening economy CC0

The key takeaways for using landscape architecture and urban design to prevent crime

Principles such as ‘Secure by Design’ and ‘Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design’ include many strategies that may seem common sense to landscape architects and urban designers. However, with pressures from budget, client expectations, and existing conditions, these principles can easily get lost. Some key issues to consider include:

- Making sure the space is well connected

- Create clear and legible circulation that is instinctive

- Diversify route options for users

- Ensure sidewalks and paths are wide enough to accommodate double pushchairs/strollers so that caregivers and families feel welcome

- Making nodal spaces that are defensible

- Providing a good mix of functions and considering including 24-hour services

- Increasing visibility by keeping planting clear of major sightlines and not creating hidden spaces with low-level planting

- Careful consideration of lighting

- Providing clear signage so that users always know where they are and how to get out

- Budgeting for good maintenance so that spaces feel well cared for and that acts of vandalism are quickly dealt with

By considering all the above tools for creating safer spaces we can reduce crime in our built environment. What other measures do you use in your designs? Do you have any particular success stories you would like to share with us?

—

Lead image: Athens night time economy CC0

Article written by Ashley D Penn with research by Emanuela Roascio

Future Housing Solutions for Evolving Cities

In an increasingly technological age, we are seeing many high-tech innovations invade our homes. Devices are becoming more and more intelligent, allowing us to alter the temperature, humidity, and lighting of our homes at the click of an app or suggestion of a voice command. The city is evolving with many innovations that improve the sustainability of the urban fabric and health of the citizens. However, there has been little advance in the design and methods of construction of housing since the Second World War. In this article, we look at innovative new solutions to housing that can provide comfortable and sustainable living in an evolving city.

Innovations in Materials

There have been many innovations in building materials in recent years, such as strong, fire resistant Cross Laminate Timber (CLT), self-healing bio-concrete, artificial spider silk, 3D printed graphene, and of course the much publicised Tesla Solar Roof. All these materials and products will revolutionize the lifecycle of a building from making it stronger and more resistant to damage to increasing sustainability through electricity generation and reduced maintenance. However, there has been little evolution in the form and function of the housing stock.

Cross Laminate Timber by Oregon Department of Forestry CC2.0

The Current Situation of Housing and the City

Tesla’s Solar Roof tiles exemplify the current trend for providing innovative technological solutions while reinforcing the design status quo. Not only are the tiles manufactured to look like traditional materials, but they are often shown installed on housing that appears to not have evolved in design for the last 50 years or so. There have been some advances in the form of housing with projects such as the world’s first inhabited 3D printed home in Nantes, France. Francky Trichet of Nantes Council notes that, “For 2,000 years there hasn’t been a change in the paradigm of the construction process. We wanted to sweep this whole construction process away.” Building via 3D printing allowed researchers at Nantes University to not only save 20% on construction costs (compared to building a similar building from traditional methods) but also to use forms such as curved walls that would be difficult to achieve by traditional means.

An Evolving City

The number of people living together has fallen in recent years with the average household size in the USA in 1960 containing 3.3 people, dropping to 2.5 people in 2010. Figures for the UK show that in 2011, the average household stood at just 2.1 people. Research by the General Lifestyle Survey 2011 indicates that there has been a significant increase in single person occupied dwellings: “The proportion of adults living alone has almost doubled in the last 40 years, between 1973 and 2011 (9% and 16%)”. Meanwhile, UNESCO predicts that from 1950 to 2030, the percentage of people living in urban centres worldwide will have increased from 30% to over 60%. This figure increases to over 80% of the population of more developed regions living in urban centres by 2030.

Cities are evolving and adapting to reflect the changing needs of their citizens. The use of autonomous vehicles is expected to increase dramatically in the future. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is impacting on street design, parking facilities, sustainable transport, and zoning.

As urban populations increase, cities are predicted to become denser. If current trends persist, the recent decrease in private car ownership will be amplified, with autonomous vehicle car sharing and walking becoming driving factors in urban design.

The Markthal from the West at dusk by MVRDV

©Ossip van Duivenbode

Future Housing Solutions

With increasing urban densification, pressures on land-use will increase. There will be an increase in mixed-use development not only at the block level but also in individual buildings. Projects like Market Hall in Rotterdam MVRDV, Cloud City by Union of Architects of Kazakhstan, in Singapore, and VINE by Marchetto Higgins Stieve in Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, and Sukupolvienkortteli in Finland by Arkkitehtitoimisto Hedman & Matomäki exemplify this mixed-use approach with recreation, retail, and service uses, such as day-care facilities included in the building.

With the rise in individually occupied dwellings and increased pressures on square meterage, communal functions within developments will increase. Buildings such as The Bartlett in Arlington, VA, USA by Torti Gallas and Partners features many shared facilities such as communal gathering spaces, gyms, gardens and dog parks, a bar, and private access to the Whole Foods store and coffee shop on the ground level.

Sukupolvienkortteli by Arkkitehtitoimisto Hedman & Matomäki Oy

Economics and Flexibility in Future Housing

Wage stagnation and increased housing prices mean the traditional model of owner-occupier housing is being challenged. Today, architects are designing residential units that are flexible so that as families expand, they can increase their living space within their current building without needing to move to another area. Superlofts is a project that creates buildings where the outer shell is built independently of the inner flexible units. Residents have a high degree of autonomy in choosing how their apartments develop and can adapt and increase their dwellings as needs arise. At an individual family home scale, buildings such as Unifamiliar, by architects Rafael Arana Parodi, Carlos Suasnabar Martínez, Amed Aguilar Chunga, and Santiago Nieto Valladares is a flexible housing unit with a central core of kitchen and bathroom facilities that can have a number of additional rooms added to it as the family grows.

Superlofts Houthavens Interior by Isabel Nabuurs

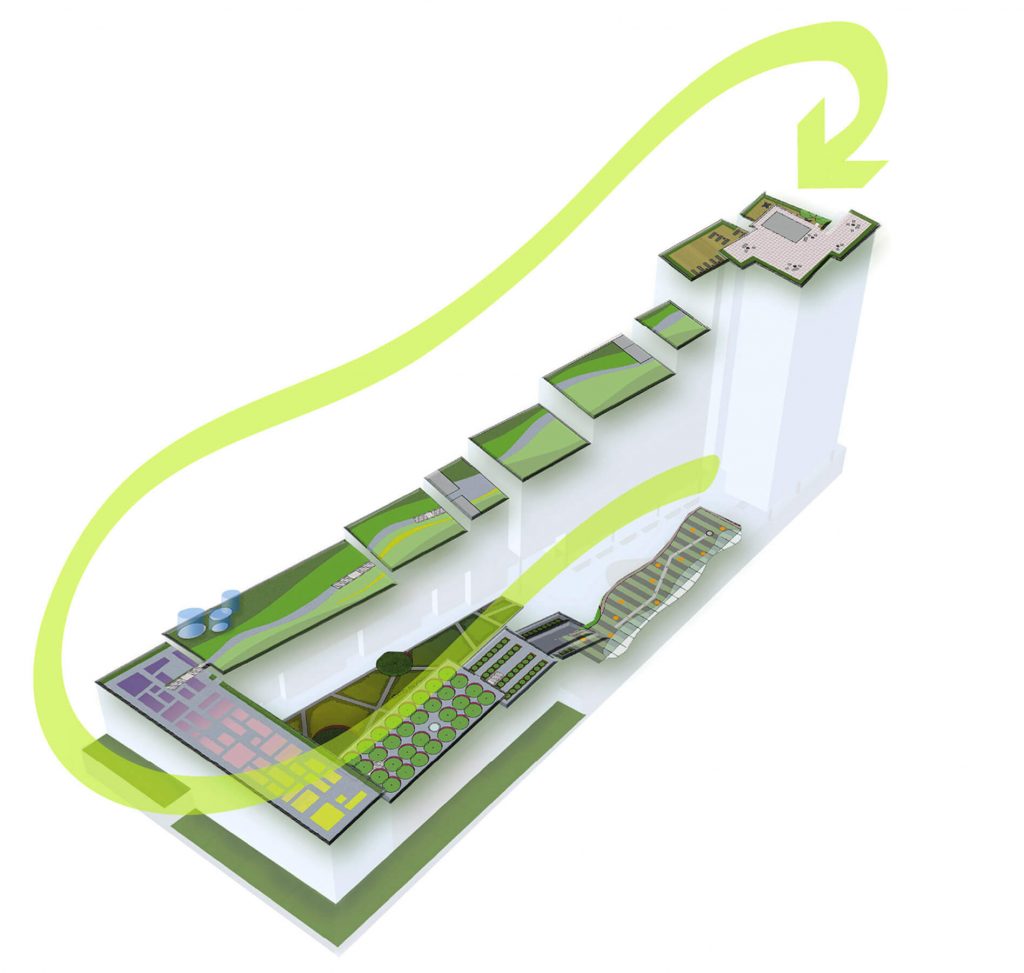

Shared Outdoor Spaces

There is a current trend for the decentralization of urban green space. With many new districts tending towards many smaller pocket parks, over one larger centralized park. The same trend is also true of semi-private and communal green spaces in mixed-use developments. Projects like Via Verde by Grimshaw Architects and Dattner Architects incorporates the defining feature of a 40,000 square foot (3,700 m2) garden that winds its way through the development, including roof terraces and shared fruit trees, encouraging healthy living.

Vie Verde by Grimshaw Architects and Dattner Architects

Future Housing Developments

Increased population, rapid urbanisation, and changes in lifestyle mean that there is increased pressure on our urban centres to become denser and provide a greater variety of functions at an increasingly local scale. Aspirations for greater sustainability require our cities to adapt to a less car-centric viewpoint with a greater emphasis on local living and walkability. Future housing solutions need to be flexible and adaptable in order to cope with these increasing pressures. New technologies allow our homes to be smarter. However, developments in housing design have only just begun to catch up with these influences. By including flexibility, adaptability, an increase in communal spaces, and increased shared green open spaces, we can meet the needs of future generations in an evolving city.

—

Lead Image: Future Housing Solutions for Evolving Cities CC0.0

Why Use Empathic Design in Landscape Architecture?

Empathic design in landscape architecture

In this article, we look at what empathic design is, and how this approach can lead to better design solutions. We are joined by international architect Moshe Katz, who shares his thoughts and experience on using empathy in the design process.

What is empathy and empathic design?

Empathy refers to the ability to see the world through the eyes of another and understand their needs, desires, and thinking. Empathy is also key to understanding the inherent properties of natural systems beyond the ecosystem services they may provide. Designers can use this empathic ability to better understand stakeholders and the end users of their spaces, to create better solutions that meet their needs, while remaining respectful of the intrinsic qualities of the natural resources of the site.

Empathy vs Sympathy

Empathy and sympathy are two related concepts. Sympathy is associated with feelings of pity, where the observer recognises the situation of the subject, but from a perspective outside of that experience. This can lead to interpretations of superiority. However, empathy places the observer in the viewpoint of the subject without external judgement.

Using human empathy in design

The international design company, IDEO.org, have produced The Human-Centered Design Toolkit which sets out how seemingly intractable problems can be overcome by a human-centric design approach. The theory describes how solutions to design problems may be sourced from the very people that the problems affect most. IDEO has published the Field Guide to Human-Centric Design, which is available as a free download on their website. In the guide, the authors discuss how empathy is key to understanding the design challenges faced in any project. They argue that a traditional approach to trying to solve problems such as inequality and poverty has disregarded empathy. By metaphorically placing themselves in the shoes of those they are designing for, designers will have a greater insight into how to solves such problems and see things from a fresh perspective. Empathic design can also challenge preconceived ideas and outmoded ways of thinking, bringing innovative ideas and solutions.

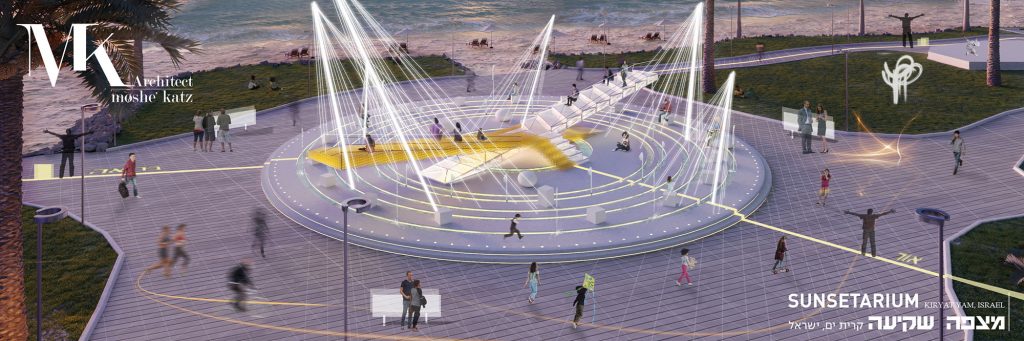

Sunsetarium by Moshe Katz

Using environmental empathy in design

Moshe Katz uses empathy as a tool for analysing the environment, human needs, and society. “The goal of the empathic designer is not to change people, but let them be who they are, free, use their maximal potentials in their surroundings.” He believes that the key to using empathy in design is ‘love’ (an approach he has developed over time): “The first tool one must acquire is an interior process of falling in love with the planning environment and people.“ He notes that this process takes away the designer’s ego, control, and need to change. Katz asks himself the question “what does this place, or this person dream to be?”

Moshe Katz’ project Sunsetarium, was born out of “a higher sensation of empathy and love towards nature and people.”He has created a shared space in Haifa, Israel, that encourages people to come together to observe the sunset and “to meet, to communicate, to be a part of the community through a natural experience- we are all an audience of a show, together.”

His approach began with “...the love of nature, the love of people, became a design approach, leading to a new form of analysis- what is special here? What does the sun dream to be? What do the people dream to be? That form of looking at things- created new design principles- leading to an ‘outside the box’ solution- an urban meeting place as a sunsetarium.”

See the video below for an introduction to Moshe Katz’ design approach.

Tips and tricks to get into the empathic design mindset

- Define your target

Make sure at an early stage the whole design team knows for whom the design is intended: all the user groups, individuals, interested parties, and stakeholders. Empathy can only be employed when the designer knows who to empathise with. - Widen your net

Good design should be inclusive. By consulting with a broad range of stakeholders, from the mainstream to those with more outlying opinions and minority groups, a greater empathy can be fostered. Some extremist points of view may be valid or founded in genuine grievances or scepticism. - Be inspired

Fully engage in public and client consultation, as well as site analysis. By getting to know and understand the stakeholders, designers can find inspiration for design solutions that might not otherwise present themselves. - Immersion

Empathy can be difficult to develop. By immersing oneself in the culture of those the space seeks to serve, landscape architects can foster greater empathy. - Get to know your team

Understanding the skills and approaches of your team can have positive effects on the design process. Often in design, differences of opinion can arise. Taking an empathic approach can help resolve disputes, come to greater understandings, and innovate new solutions. - Communication

Having empathy means being able to understand other people and how they communicate. It may be appropriate to alter how the design and consultation is communicated depending on the target audience. - Intuition

Taking an empathic approach can allow instinctive intuition to flourish. This can be exploited during the concept and ideation phases of the design process to inspire innovative solutions. - Roleplay

When empathy is difficult to foster, it can be useful to role-play different scenarios as different users or stakeholders. This will help a designer to explore issues from outside their immediate perspective. - Practise empathy

A 2013 study published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that humans are naturally good at empathising. However, due to personal experiences, we can lose this innate ability over time. The good news is that empathy can be increased through practice. Due to the neuroplasticity of the brain (and particularly the supramarginal gyrus which governs empathy), humans can get better at empathising through practising empathy. Therefore it stands to reason that the more designers practice empathic design, the better they will become at it.

Sunsetarium by Moshe Katz

Lessons in empathic design

Empathic design relies on a designer being able to see things from another’s perspective. By practising empathic design, landscape architects can create spaces that better serve their target audience. This involves an approach to the site, users, and stakeholder engagement that is open, intuitive, and unbiased by preconceived judgements and intentions. By practising the 9 steps above, a designer can increase the level of empathy in the design process, and thus reach innovative solutions that truly solve design problems.

Credits:

Article co-written by Ashley D Penn, Jolma Architects, and Moshe Katz, Architect – Artist.

Moshe is an international architect and artist specialising in the critical stages of conceptual project development, architectural primary design, strategic planning, and urban branding.

Lead image: Sunsetarium by Moshe Katz

Pocket Parks as Urban Acupuncture

In traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture refers to the insertion of fine needles into specific parts of the human body with the aim of treating a range of symptoms. In a similar way, urban acupuncture refers to the theory of manipulating the urban fabric on a small scale to affect greater socio-environmental impacts. In this article, we look at how pocket parks might be used as an urban acupuncture tool.

Urban acupuncture

The phrase ‘urban acupuncture’ was first coined by the Spanish architect and city planner Manuel de Solà, and was later popularised by Finnish architect Marco Casagrande. Key to the theory is understanding the city as a holistic whole, more like a living being than a collection of dissident phenomena. Urban acupuncture theory proposes that problems within the city can be alleviated through small interventions at specific localised sites. Sites are selected through an integrated approach of data gathering, community involvement, and site analysis. Once selected, interventions are designed and implemented to enable greater impacts on the surrounding areas and wider afield throughout the city. One common misapprehension about urban acupuncture is that sites and interventions must always be small. Tiago Olivera of Arup argues that one of the most important features of urban acupuncture is that the intervention should be swift. Quick to implement, and quick to alleviate the stresses on the city. Another important feature of urban acupuncture is that it should follow a ‘bottom-up’ approach. Many larger-scale interventions take a long time to implement, take up vast swathes of land, and cost great sums. Often local residents can feel that these grand plans are forced upon them. The opposition to the proposed garden bridge in London by Heatherwick Studios demonstrates the level of hostility a top-down approach to planning can bring.

Pocket parks

Pocket parks are small-scale parks or gardens that provide green space for local residents, close to where they live or work. Key features of pocket parks include their small scale, community focus, and location (check out Land8’s 7 Top Pocket Parks: Small Spaces With a Huge Impact for examples). Location is of the utmost importance to the success of pocket parks. Ideally, residents shouldn’t have to walk more than 5-10 minutes to reach their nearest pocket park. They should also be located at nodal spaces, where local public transport links, roads, footpaths and greenways, and local services such as shops come together.

Paley Park New York by Aleksandr Zykov CC2.0

Pocket parks as urban acupuncture

Pocket parks offer opportunities for urban acupuncture due to their scale and relatively low installation costs. Providing large green recreational spaces can be expensive for a local authority. However, pocket parks that utilize derelict land can cost as little $150,000. There are often a number of funding bodies that can help a local community realize a pocket park.

The greening of derelict land can have impressive results for the social and cultural well-being of residents. Research from the University of Pennsylvania revealed that when vacant plots were greened, residents in low-income neighbourhoods reported “significant decreases” in feelings of depression, and lower cholesterol levels. The study even noted a significant reduction in gun crime in the area surrounding the interventions. In these cases, the interventions were minimal, often just cleaning up the lot and laying it to grass at an average cost of $1,500.

When considered as urban acupuncture, pocket parks can lead to investment and regeneration in an area. Architect Jamie Lerner notes that quick (and even temporary) interventions such as pocket parks can demonstrate how other interventions can be implemented. He points to Paley Park in New York City as an example of how a well-implemented pocket park can lead to urban regeneration. He also notes that pocket parks can alter the course of local planning, often stimulating other interventions including investment in green infrastructure such as urban greenways.

Sitting on an empty lot in central Taipei, Cicada by Casagrande Laboratory is an urban acupuncture intervention that comprises a grassy open space with a woven bamboo cocoon measuring 34 meters (112 feet) long. The intervention intends to create a conversation between modern man, the city of Taipei, and the reality of nature. Although the intervention ticks the boxes of being small and locally focused, the real key to the success of interventions such as this is the fluidity of the program. The site and structure can be used for a number of community activities, most notably as a lounge for the local university students.

Cicada_night_interior_Marco_Casagrande_by

Pocket parks and urban regeneration

There have been several studies suggesting that the implementation of pocket parks has positive effects on property values. For example, one 1973 study noted that properties immediately facing a park had on average a 23% greater value than that one block away. More recent studies point to the importance of the quality of the park in increasing property value.

One possible criticism of using pocket parks as urban acupuncture could be that the urban regeneration it fosters can contribute to gentrification. Gentrification is the term used to describe the displacement of low-income residents by those of higher income. With an increase in property values comes an increase in rents. This is often associated with urban regeneration, or where previously affordable, but less desirable areas become more fashionable. This has been evidenced in areas of Manhattan facing the High Line.

High Line Park – New York City – July 09 by David Berkowitz CC2.0

Balancing pocket parks and urban regeneration

Pocket parks are an ideal tool to consider in urban acupuncture. Quick and cheap to implement, they can have positive effects on the health and well-being of the local residents, encourage entrepreneurship through pop-up shops and services, and have positive effects on property values. Key to their success seems to be in the careful consideration of their placement and use, and a community participatory ‘bottom-up’ approach. This is one of the tenets of good urban acupuncture. It seems successful projects are not the headline-grabbing big scale or expensive projects, but the small-scale, quick to implement, projects of low cost but high value.

—

Article written by Ashley D Penn with research by Valeria Currò

Lead Image: needlecrowd.com

How Landscape Architecture Mitigates the Urban Heat Island Effect

Global temperatures are rising. This is especially felt in urban areas due to the urban heat island (UHI) effect, where temperatures can be 10oF (5.5oC) higher than the surrounding countryside. This phenomenon is due to several factors that combine to alter the local microclimate of an urban area. However, several techniques can be employed by landscape architects to help combat the local rise in temperatures, saving money, reducing global warming, and making a more pleasant environment to live and work.

In this article, we look at what the urban heat island effect is and what landscape architects can do to combat it.

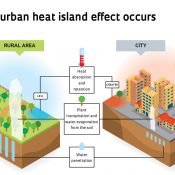

What is the Urban Heat Island Effect?

Objects of different colours reflect varying amounts of light. Surfaces with a greater albedo (or lighter colour) reflect more of the sun’s energy. Darker objects tend to absorb more radiation and therefore heat up more quickly. As our cities are usually made of darker materials like concrete and asphalt, they absorb comparatively more energy from the sun and therefore heat up more quickly than the surrounding, lighter coloured and vegetated countryside.

Cities tend to drain surface water quickly into sewers, where it is trapped, and cannot evaporate as easily. In rural areas groundwater drains through the soil and is transpired by plants. The evaporation of water in rural areas adds a cooling effect to the local climate.

Finally, things like air conditioning and vehicles add small amounts of heat to the air in cities, contributing to the UHI effect.

Mitigating the Heat Island Effect

There are various ways in which the UHI effect can be mitigated through technology and the use of landscape interventions.

Technology that Reduces the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

Reflective surfaces

One way to decrease the amount of the sun’s energy that is absorbed by a city is to use lighter coloured materials. However, light colours also create glare, which is not only annoying for city residents but can cause problems for drivers. One solution is to use lighter coloured paints on higher roofs. These are known as ‘cool roofs.’ Another technological solution is to use special reflective paints that absorb visible light while reflecting invisible light. As these paints do not reflect visible light they can be darker in colour. However, the extent to which reflecting only infrared light has on the UHI effect is still under debate, with some experts claiming that the benefits are minimal.

White roof and skylights on Las Vegas, Nev. Walmart_Walmart corp. CC2.0

-

Solar panels

Another approach is to actively use the radiation from the sun to generate electricity. Photovoltaic panels can be used to provide shade to a building, preventing the thermal mass of the building heating up, and radiating its stored heat at night.

Green Ways to Reduce the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

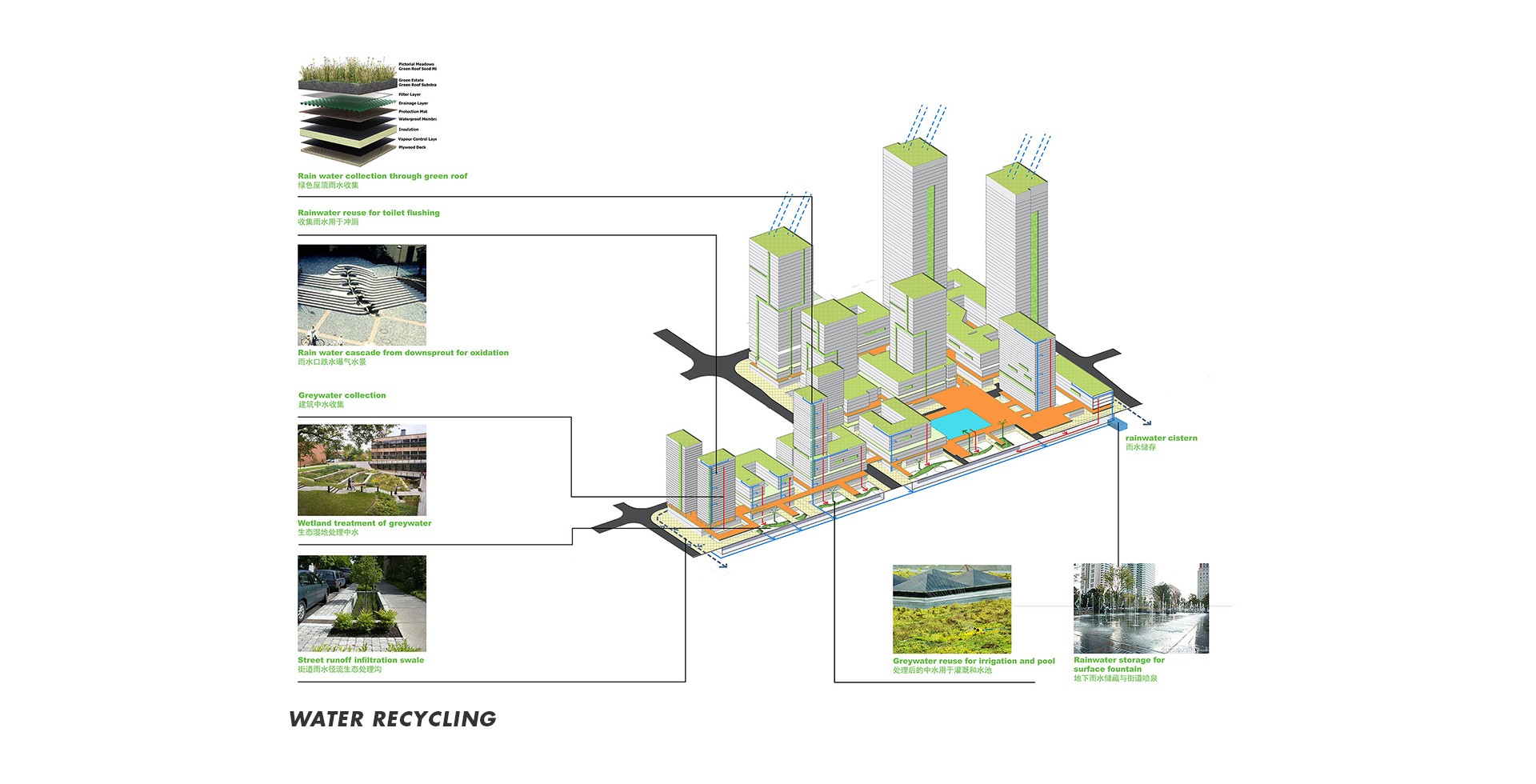

Green roofs and walls.

The benefits of green roofs on stormwater management, biodiversity, habitat creation, and building insulation are well documented. However, they also have an important role to play in mitigating the UHI effect. Not only does the higher albedo of the plants reflect more of the sun’s energy, but as the plants transpire the surrounding ambient temperature of the building is lowered through evaporative cooling. Green walls have similar effects in reflecting more light and evaporating moisture.

-

Permeable surfaces

Tests have shown that while wet, a permeable paving system of interlocking concrete blocks performed localised cooling better than impermeable surfaces. For permeable surfaces to have a significant effect on the UHI effect it is important to note that there should be regular rainfall to evaporate. Also, the depth of the water table below the surface also impacts upon the permeable paving’s cooling efficiency.

-

Green parking lots

Vegetated surfaces like green parking lots combine many of the benefits of green roofs and permeable paving. All too often parking lots are made of dark coloured, impermeable asphalt. However, by using a material like concrete Grasscrete, or porous plastic paving units, the cooling benefits of vegetation and permeability can be exploited, while still maintaining a degree of usability.

-

Urban Trees

There are several ways in which trees help in mitigating the UHI effect in a city. As tree leaves are usually lighter in colour than the surrounding urban fabric they reflect more light. Trees also affect their local atmosphere by transpiring. A large oak tree can transpire as much as 40,000 gallons (150,000 litres) per year. Street trees are particularly good at shading buildings and sidewalks, effectively filtering the amount of radiation that reaches the lower albedo surfaces.

Harvesting the Power of Water to Reduce the Urban Heat Island Effect

-

Incorporating water into the landscape

As bodies of water evaporate, they cool their environment. By increasing the surface area of any water feature in the urban landscape, the amount of evaporation is maximised. Therefore, there is a strong argument for including water in any urban landscape, whether it be a lake, pond, or daylighting an old stream that has been covered over, such as the La Rosa Daylighting Project in Auckland, New Zealand.

-

Rainwater harvesting

One of the limitations of the cooling effect of permeable paving is that when there is no rainfall to evaporate, they do not cool their environment. Traditionally, the focus on stormwater management has been to quickly discharge the peak flow into stormwater drains or encourage infiltration. However, by harvesting rainwater, storing it, and allowing it to evaporate from surfaces, not only helps to level out the peak flow of storm events, but it also extends the time permeable paving has a cooling effect.

RBC Rain Garden at the London Wetland Centre by Marathon CC2.0

-

Rain gardens and swales

Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) have proven benefits for stormwater attenuation. Rain gardens and swales are forms of SUDS that collect rainwater during storm events and allow it to slowly infiltrate into the ground. As they retain the water for a period, the water has a greater time to evaporate. By including planting, rain gardens also perform evapotranspiration, cooling the air further.

Landscape Architecture Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect.

There are several ways architects and landscape architects can reduce the urban heat island effect. Through technological means, the albedo of surfaces can be increased to reflect more of the sun’s energy, thus reducing the amount of energy absorbed by buildings.

However, there are also a great many tools at the landscape architect’s disposal that can mitigate the UHI effect. By incorporating green roofs and green walls some of the sun’s energy can be reflected, rather than absorbed. By including shade producing deciduous street trees into the streetscape, sidewalks and buildings can be shaded from the sun. Permeable paving can encourage evaporative cooling at the street level, and when used in conjunction with rainwater harvesting can provide maximum cooling when it is needed most. Finally, many sustainable urban drainage system tools can be used to retain water in the landscape, providing evaporative cooling. All these measures will help reduce the ambient temperature of the local microclimate and mitigate the overall urban heat island effect.

LEAD IMAGE: Urban heat island effect by Alexandre Affonso

Landscape Architecture in Walkable Cities

For too long the city has been designed for cars. Pedestrians can often feel like second-class citizens, as cities are much easier to drive into than walk through. Recently, built environment professionals have been advocating improving the quality of our built environment by making cities easier to navigate by foot. In this article, we look at how landscape architects are especially well qualified to implement walkability in our cities and how landscape architecture can improve the quality of our walkable urban environment.

Walk and Walkability

A simple definition of a walkable city or neighbourhood is one that is enticing to pedestrians, encouraging walking over other forms of transport. Professionally, the term covers several phenomena. In her 2015 paper ‘What is a Walkable Place? The Walkability Debate in Urban Design’, Ann Forsyth of Harvard University identifies three definitions of walkability in common use today:

-

Means or conditions

The means by which cities can be walkable i.e. compact, traversable, physically enticing, and safe

-

Outcomes and performance

Making places lively and sociable and inducing exercise

-

A proxy for better urban places

A focus on how walkability can provide holistic solutions to a variety of urban problems.

The Benefits of Walkable Cities

Walkable environments come with a host of health, social, and economic, benefits. For example, walkable neighbourhoods can positively impact the health of their residents by reducing blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes, and improving mental and cognitive functions. Walkable cities can improve neighbourhood cohesion through increasing social interactions. Locally, walkable neighbourhoods provide better environments for living such as cleaner air, lower levels of traffic noise, and fewer road traffic accidents. Globally, the resulting reduction in motor vehicles reduces CO2, CO, and N2O emissions.

On a personal level, walkable neighbourhoods have the capacity to positively impact upon an individual’s finances. Personal car ownership can account for up to 20% of a person’s income. Not paying for parking costs can also add up over a year. At a community and national level, healthier people rely less on public healthcare, thus reducing the burden on public expenditure. The walkability of a neighbourhood also has positive impacts on crime and urban decay, as well as being a reliable predictor of higher housing valuations.

How Landscape Architecture Impacts Walkability

At a strategic level, things like urban density and traffic planning play a pivotal role in the walkability of a city. Many of the Top Ten Walkable Cities have great infrastructure for walking. If people can safely walk from home to work and to the shops, then they will. However, the means by which pedestrians navigate their city falls within the remit of landscape architecture.

Key to encouraging walking in the city is making the environment inviting for pedestrians. This means making routes that are attractive, functional, and safe. Several landscape interventions can assist in meeting these aims.

Vancouver by Lissandra-Melo-

-

Street Trees for Safety

Street trees can slow vehicular traffic by an average of 7-8 mph (11-13 kph). By incorporating trees into the streetscape at a density of one per 15-20 feet (4.5 m – 6 m), not only does the local environment benefit from the well-known effects of reduced heat island effect and power consumption, and improved stormwater management; but also, streets become safer. A 2006 study by Kathleen L. Wolf notes that street trees resulted in reductions in traffic accidents of around 45%.

-

Pocket Parks

The inclusion of well-designed pocket parks may seem like an obvious aid to increase the walkability of neighbourhoods, but their placement and distances between them need careful consideration.

In walkable neighbourhoods, several small pocket parks encourage walking through their accessibility by foot. The National Recreation and Park Association recommends placing pocket parks within a five to ten-minute walk of its users. This translates to a maximum interval distance of not greater than 1.2 miles or 2 kilometres between parks. Pocket parks should be placed along well design routes and be designed with site specificity in mind. They may take the form of urban squares, green parks, community gardens, or community orchards. They should be placed at nodal spaces and be supported with surrounding mixed-use development.

-

Linear parks and urban greenways

There have been some famous examples of linear parks retrofitted to existing infrastructure in recent history, notably the infamous Highline and Promenade Plantée. This trend for linear parks has been picked up in projects including, The Green Line in New York and The Meadoway in Toronto. The Madrid Rio project by West 8 and MRIO arquitectos goes even further and integrates large linear green spaces like Salón de Pinos and relocating a major road and parking underground to accommodate the Avenida de Portugal, a vibrant new public open space.

Urban Greenways

In terms of walkability the often-underappreciated smaller sibling of the linear park, the urban greenway, has much to offer. Urban greenways provide many of the same benefits of linear parks, but on a smaller, and often more affordable scale. One of the main benefits of greenways over linear parks is that they take up less space. Much like pocket parks, urban greenways can facilitate walking at a local scale, provided they connect with useful nodal spaces that are not too far from each other. One key consideration when designing greenways is visibility and safety. Chuck Flink, founder of Greenways Incorporated urges that, although greenways have a lower than average crime rate, they should be designed so that users feel safe. He suggests regular exit/entry points to not only increase connectivity, but also the feeling of safety as users have regular ‘escape routes’. Visibility lines should be kept clear by the careful consideration of planting, preventing places that people can hide in.

All Walks of Life

Walkable cities have numerous social, economic, and health benefits. At the strategic level, increasing density and mixed-use development, and placing an emphasis on the pedestrian can facilitate walkability in a city.

Landscape architects can make a substantial impact on the walkability of neighbourhoods through the inclusion of well-designed green infrastructure. A carefully considered tree-lined streetscape can calm traffic, improve aesthetics, and provide a safe environment for pedestrians. Well placed pocket parks can act as attractors, encouraging people to walk from place to place. Linear parks and urban greenways provide physical structure for walking, as well as a more attractive option than travelling by vehicle. The key to successful implementation of any of these is good site-specific design and integration with the surrounding urban fabric.

—

LEAD IMAGE: Pedestrians by Free-Photos CC00

How Autonomous Vehicles are Influencing Urban Design

The rise in autonomous vehicles is happening faster than many people think. NVIDIA CEO, Jensen Huang, says that fully automated vehicles will be on our roads by 2022, while Scott Keogh, Head of Audi America has promised that Audi would have its first self-driving cars ready to purchase by as early as 2020.

So, with the rapid acceleration of the autonomous vehicle (AV) market, what are the main challenges we face as urban designers? And how will autonomous vehicles affect the urban fabric of our cities?

Towards a New Autopia?

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, our urban and suburban environments have been primarily designed for private car use. However, there has been a recent reduction in the ownership of private vehicles. Thanks to on-demand ridesharing services like Uber and Lyft, and specific vehicle demand management policies.

Drivers of change

The reduced number of vehicles on our roads has already begun to shape the fabric of the city. Projects like Berges de Seine Paris and Rhone River Bank Lyon show how spaces in the city that were once dominated by the automobile can be converted to public open spaces that serve the city and its inhabitants.

Berges_du_Rhone_Pont_Guillotiere by ThomasBigot

This is a trend set to continue. As any technology (and its associated manufacturing techniques) develops it becomes cheaper. This will drive the demand for AVs as more consumers and companies will be able to afford the technology. Some experts predict that sales of AVs will pass 33 million a year by 2040 (representing one-quarter of all car sales).

Rethink (a think tank focused on the future of technology) believes that private car ownership will reduce in favour of on-demand services where massive fleets of AVs are owned by private companies. However, the recent tragic events of Uber’s fatal autonomous vehicle accident has spread skepticism among the media.

Finally, the policy on how AVs may be driven in our cities is somewhat behind the technology and implementation. The Global Survey of Autonomous Vehicle Regulations notes that only 33 US states have legislation covering self-driving cars on public roads, and other countries like the UK, Netherlands and Sweden only have fully enacted legislation covering the testing of autonomous vehicles. Many other countries have no legal framework covering AVs.

Updating the hardware to meet new software

If by 2030 some 25% of cars on the road will be AVs, we should be adapting our cities now to accommodate this change and preparing for the time when all cars will be autonomous.

Currently, AVs use LiDAR to scan the road ahead. This technology is best at reading the road ahead at between 100-200 m. However, by incorporating roadside sensors along the length of a road, information about road condition, weather, and unexpected events can be relayed to all cars simultaneously. It is likely we shall need to accommodate some form of sensing equipment along our streets in the future. A key challenge is how this is incorporated into the streetscape and could mean the difference between an ugly retro-fitted solution, and a properly integrated system that augments the built environment.

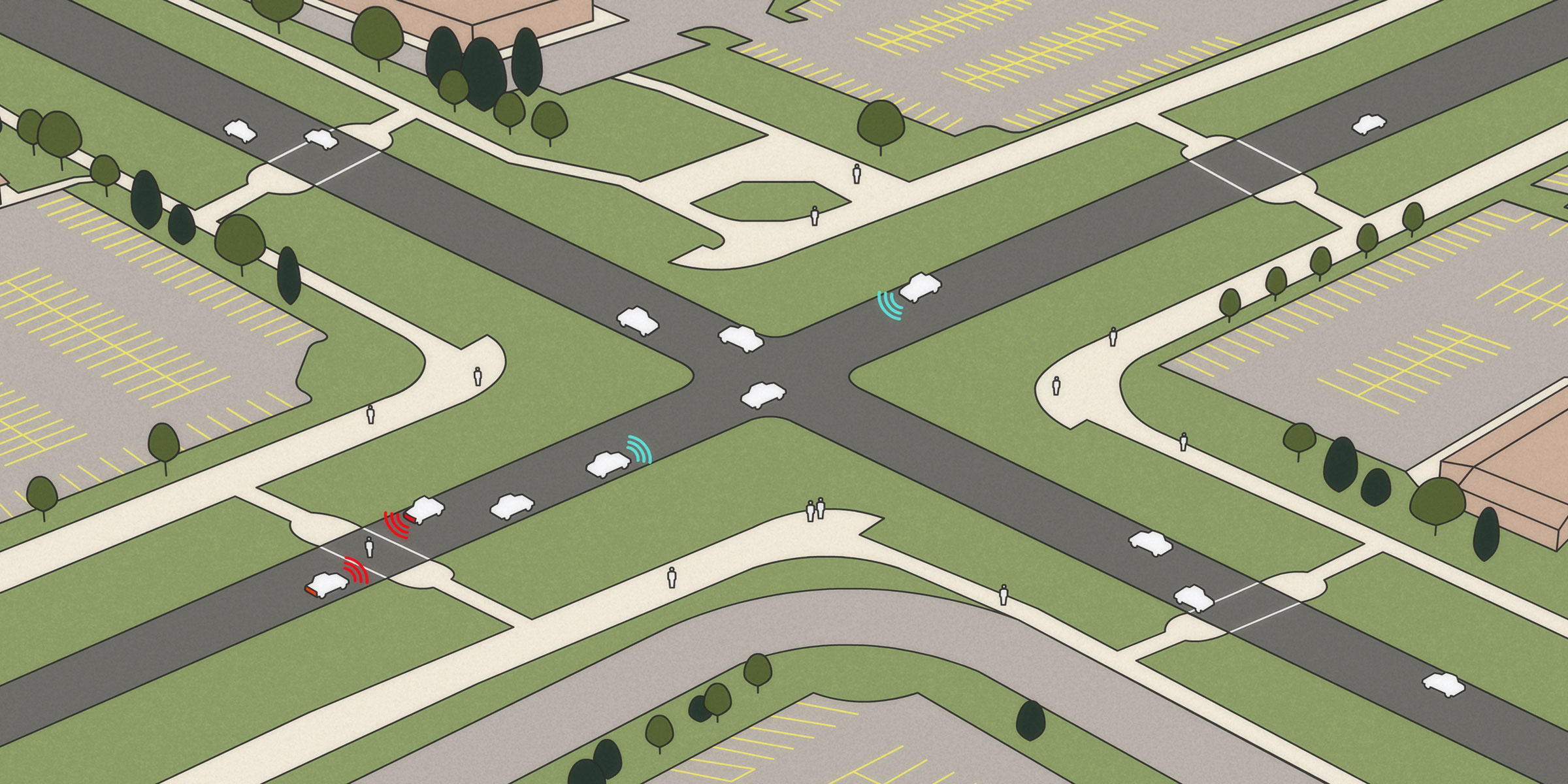

Image courtesy of Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. (SEH®) http://www.sehinc.com

One benefit of better connected AVs is the opportunity to give higher priority to pedestrians. The present car-centric design of our cities means that pedestrians are forced to walk to the nearest road junction or underpass to safely cross the road. With cars being driven by computers with faster reaction times, truly shared surfaces can be used throughout the city. A walkable city with a more attractive environment for pedestrians can have dramatic effects including lower crime, physically and mentally healthier citizens, and increased property prices.

With reduced numbers of cars comes reduced spatial requirements. Even if numbers of cars do not fall dramatically, some experts predict that efficiencies in automating traffic flows mean vehicles will be able to drive at higher densities. Roads will, therefore, be able to be narrower, with fewer lanes. In existing urban areas this means wider sidewalks that can accommodate other functions such as linear parks, sustainable urban drainage systems and dedicated drone delivery lanes.

When 100% of vehicles are self-driving, there will no longer be a need for vehicular road signage and traffic lights. This presents an opportunity to de-clutter our streetscapes and come up with innovative new solutions to allow AVs to communicate with each other. Pedestrian wayfinding will remain a consideration, but without the need to display signage for motorists, we can rethink how people navigate the city.

Parks instead of parking

The use of shared on-demand vehicles will reduce the redundancy of cars as they are in use for longer periods of time. Real-time relaying of information directly to AVs will reduce the time spent searching for parking places. Self-driving cars will be able to drop off their passengers at their destination, and then leave to either pick up a new passenger or find a centralized parking and charging location. The reduction in localized car parking facilities will free up more space in the city for parks such as at Tongva Park in Santa Monica by James Corner Field Operations.

On a smaller scale, the reduced ownership of cars will result in private homes not requiring dedicated garages and driveways. This will affect housing design allowing for the development of a higher density within cities and the suburbs.

Future cities

For the last 60 years or so, the private car has dominated urban design. But the rise in autonomous vehicles presents some unique challenges and opportunities to reassess how our cities are designed.

The increase in on-demand driverless vehicles will result in more space in our cities for green infrastructure. Areas that were once dominated by localized parking lots can be converted into pocket parks. Wide boulevards and urban highways can be repurposed into pleasant greenways. Roads can become narrower, allowing for better sustainable urban drainage systems and blue infrastructure. Higher priority can be given to pedestrians in truly walkable cities that will benefit our mental and physical health.

The technology behind autonomous vehicles is progressing at a fast pace. While policy and infrastructure design might be slightly behind the technological advances, it is time designers started to think about the changes that will come and plan for a future in which the car is no longer.

—

Lead Image: Hämeenlinnanväylä kaupunkibulevardina by Mikko Uro c. Helsinki City

8 Ways AI is Shaping the City

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is a buzz word that is currently taking the world by storm. AI has infiltrated almost every sector and is being used to create better products and services. But what exactly is AI, and how might it effect urban design? What are the potential benefits and things designers need to consider for the future? In this article we look at some of the ways AI is already influencing the city and examine what impacts these may have on our profession in the future.

What is Artificial intelligence?

Artificial intelligence is the term used to describe how machines can be trained to learn from experience using data analysis and advanced algorithms to better achieve specific goals. Although the term was originally coined as early as 1956, AI has become increasingly popular in recent years with advancements in information technology and data gathering.

1. Artificial Intelligence Will Change Street Design

Autonomous or self-driving cars are already a reality. Finnish firm VTT has developed a fully autonomous vehicle called Marilyn that uses LiDAR to ‘see’ through adverse weather conditions like fog and snow to detect and avoid pedestrians in the road. Artificial intelligence is used to process information gathered from sensors and share this information with other vehicles in an interconnected network.

This advancement in urban navigation will result in less congestion in our cities. It will also be possible to design safer shared surfaces where vehicles and pedestrians can coexist without incident. Self-driving cars are likely to amplify the current trend in reduced car ownership. Think tank Rethink predicts that by as early as 2030 ‘95% of U.S. passenger miles traveled will be served by on-demand autonomous electric vehicles’ reducing the need for personal car ownership. This will result in an overall reduction in the number of vehicles on our roads, meaning that streets will be able to be narrower, with fewer lanes.

Image courtesy of Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. (SEH®). http://www.sehinc.com/

2. Autonomous Vehicles will Alter the Fabric of our Cities.

‘On-demand’ autonomous vehicles will enable users to hail a car whenever they need using an Uber style service. This means that parking facilities can be centralised, reducing the need for local parking lots and on-street parking. These redundant parking lots may make way for pocket parks, urban greenways and redevelopment opportunities.

3. Energy Efficiency

Perhaps one of the more obvious ways in which AI can impact the city is through quick and smart analysis of data to enable energy efficiencies. For example, UK based firm Vivacity is using AI to develop more sustainable traffic management through better, automatic, traffic light sequencing. IBMIBM‘s Watson Internet of Things and Echelon Corp. have got together to develop an innovative intelligent LED streetlight control system called Lumewave. Utilising Watson’s ‘cognitive computing system that learns from experience’, the system will use both real-time data gathered from sensors within the light fittings, as well as external sources such as news and weather to intelligently adjust lighting levels as needed.

4. Automated Planning

One of the key benefits of AI is its ability to process large amounts of data quickly an efficiently. This has great implications for policy and spatial planning. For example, advanced computer simulations can better predict urban flooding, helping to identify opportunities for development, and minimise flood risk. AI allows designers, policy makers, and politicians to gather data about public realm usage to make better decisions regarding resource allocation and spatial planning. In the future, Ai will also enable designers to run virtual computer simulations of their proposals to analyse their efficiencies and help design out conflicts, crime, and antisocial behaviour.

5. Predict and Mitigate Urban Decay

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University have developed an AI system that is able to predict urban decay in five American cities. By showing groups of people 1.6 million pairs of photos of urban environments taken several years apart and asking them questions about their preferences for these environments, the AI system was able to predict which urban environments would fare better in the future, and which would decay. Interestingly, the research identified that higher levels of education and access to business districts were a better predictor of the success of neighbourhoods than either income or house prices

MIT Creative Commons CC0

6. Increase Opportunities for Recreation

A possibly contentious issue is AI’s role in the workplace. Some experts predict that in the short-to-medium term AI may allow for greater automation of tasks, thus reducing the number of hours humans need to spend in work. This reduction in work time and increase in leisure time will result in a reduced demand for office space in the city and increase demand for leisure facilities including parks and urban green spaces

7. Augmenting the City

In 2016 the phenomenon of Pokémon Go swept the globe. This augmented reality (AR) game saw peak users of over 19 million worldwide, all of whom were out in the city visiting Pokestops and Gyms; many of which were located in parks and other green spaces. The application of AR can impact upon how people use the city, with companies already offering AR apps to help explore urban environments. The data generated from this can also be processed by AI and used to analyse patterns of behaviour in the city and influence the positioning and nature of urban infrastructure. In the future it may be possible for designers to create spaces that can host an almost infinite number of designs, as each user experiences an individual (augmented) reality of a space

8. Smart Solutions, Smart City

AI plays a key role in the Smart City concept. Many municipalities are starting to adopt the concept of Smart City in their governance. This involves data gathering and processing to assist in improving cities and making efficiencies through experimentation and innovation. For example, in the city of Hangzhou in China the local government developed the concept of ‘City Brain’ to use AI to create a smart neural network across the city to analyse and process data from a variety of sources including social media and water supply. The results lead to changes that reduced crime, congestion, and fewer road accidents.

AI in the future

Artificial intelligence is already being implemented in areas as diverse as autonomous vehicles, virtual planning, and augmented reality to improve our cities. In the future AI will further unlock the potential to process vast amounts of data quickly, to make better spatial planning and design decisions. If you are currently using AI in your work, or plan on adopting AI to help develop specific solutions, we would love to hear about it in the comments section below.

- 1

- 2