Author: Land8: Landscape Architects Network

How to Design Out Crime with Landscape Architecture

Is it possible to design out crime with landscape architecture? We take a closer look at what can be done. It is a well-known fact that the role of landscape architecture goes far beyond aesthetics. Creating functional and dynamic spaces, improving access to the outdoors, making streets and squares more friendly for the disabled, and inspiring sustainable measures in a city are but a few of the many opportunities this field has to offer. But did you know that landscape architecture helps in fighting crime, too?

From “Eyes Upon the Streets” to Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Design has always been associated with security and safety in terms of natural conditions such as fire, flooding, and all kinds of unavoidable happenings. But the understanding of how the shaping of open spaces can help in reducing or increasing crime didn’t begin until the early 1960s.

The front cover of “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”.

Lighting for Nocturnal Safety

As Jacobs had highlighted in her book, good public lighting enhances vision and therefore reassures individuals at night. Thus, in a landscape architecture project, lighting shouldn’t be used solely for the purpose of making the pathways visible, but also to improve the visibility of the surroundings in the dark, when crimes usually take place. The aim is not to overuse lights and turn night into day; a creative use of lighting technology can keep outdoor spaces well lit without losing their natural nocturnal feel.

How a Dazzling Lighting Scheme Design Transformed a Dark City Center. Photo Credit: Torico Square by b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos, Teruel, Spain

Good Visibility

Improving visibility is not only about putting up good lights. Paths and corners that do not provide good visibility conjure a feeling of uncertainty. It is therefore the task of landscape architecture to create outdoor spaces that avoid total isolation. While semi-secluded spaces such as secret gardens are often desirable, playing with levels can make the formation of partially enclosed spaces still possible while maintaining the needed safety. The park of André Citroën in Paris is a good example of that, as a series of visually detached gardens was shaped while still being visually accessible from the elevated bridges and other higher spots of the park.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Aerial view of Parc André Citroën. Credit: Andrew Duthie, CC 2.0

Social Control

The “eyes upon the streets” contribute in reducing crime. In an active street or public space, the victim of a crime will not find himself short of rescue and assistance. But how can landscape architecture make a space more active?

The outdoor gym in a modern community park in Kildebjerg Ry, Denmark. Photo credit: Mikkel Frost

The truth is that design can very much influence the way individuals approach a certain place. If it is inviting and leaves room for activities, it will not end up being abandoned. The outdoor gym in a modern community park in Kildebjerg Ry, Denmark showcases how new opportunities can turn a park into a more vibrant and used place.

Avoidance of a Sense of Neglect

A park or square with unmaintained plantings and broken paving does not only repel users, it also invites crime because it suggests that the space is devoid of human activity and therefore an easy target. Making landscape elements look neat and taken care of can aid in preventing the space from becoming a target of criminal behavior. Plaza De La Luna in Madrid, Spain, illustrates how the materials chosen for designing a space can avert vandalism in order to keep a public space appealing for visitors. Rusted CorTEN steel — a material which is very hard to glue or paint on — was used for the refurbishing of the square.

Plaza de la Luna by Brut Deluxe and Ben Busche Architects.

Good Connection Between Public and Private

In his theory of defensible space, Oscar Newman mentions the juxtaposition of public and private spaces as an effective means of natural surveillance. A good communication between architecture and landscape architecture is crucial for an efficient level of security. The design of buildings should maximize the visible connection with the outside through windows and transparent material. In an attempt to improve the feeling of subjective safety in the housing project Frauen-Werk-Stadt in Vienna, Austria, stairways and passages have been separated from the outdoors with transparent glass. This is an effective measure that promotes surveillance.

Photograph taken by: Dalia Zein

Realize That Different Users Have Different Needs

Studies conducted by geographers and planners starting in the 1980s have shown that women are more likely to avoid access to public space than men for reasons of safety, although women are attacked more often in their own homes rather than outside. This fact requires landscape architects to be aware of how the design of a space can affect different users. Safe Cities program is an UN-Habitat initiative that conducts participatory walks with women in certain neighborhoods to identify unsafe places and how to change them with the consideration of the women’s ideas. WATCH: Because I am a Girl Urban Programme: Delhi Documentary

The only downside is that it is really difficult to measure whether a new design really does help reduce crime, as many assaults go unreported. On the other hand, the popularity of a place either increases or decreases with a new design, and that is already one big step that landscape architecture can make to keep crime away.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Dalia Zein Return to Homepage

Designed for the Future | Book Review

A book review of “Designed for the Future: 80 Practical Ideas for a Sustainable World” by Jared Green. In Designed for the Future, Jared Green tackles the topic of contemporary design ideas that are creating a more sustainable world. The format of the book is a direct result of his approach to research for the publication. In asking eighty designers, landscape architects, planners, and engineers what they believed was moving the allied design professions to a more sustainable future, he compiled eighty ideas and project case studies which are featured in the book. Green starts the dialogue about the need for green and environmentally conscious design with professionals and then transfers that to a reader friendly format appealing to a wide audience. Not only is the book a useful tool for project ideas but it is also a strong starting point for case study research as it provides a concise yet in depth project snapshot of each idea. The work is a summary of cutting edge, innovative, creative, and technologically advanced ideas designers are deploying today for a more sustainable tomorrow.

Front cover of Designed for the Future.

Designed for the Future

Judge a Book by its Cover

The comfortable size of the book makes it appealing to stash on a bookcase at home, on a desk, or in a bag for traveling. Graphically, the cover is appealing and establishes a design language that is carried throughout the book, from front to headings to subheadings to back. More successfully, the excerpt on the back cover is but a few sentences, followed by a three-column list of names, instead of an overbearing, multi-paragraph synopsis. The list names 80 global leaders in sustainable design, including architects, landscape architects, journalists, urban planners, environmental leaders, and artists, who all share their insights and philosophies within the book. First impressions are strong, as this is a well-packaged book that is easy to leaf through.

Page-by-Page Overview

The book is a compilation of 80 ideas offered up by those 80 sustainable design leaders, each with a one-page write-up and supporting images. For a casual reader or someone looking for quick inspiration, this is a great book to flip through. Since the explanations are short, the reader can learn a wealth of information about a topic or project in just a few minutes.

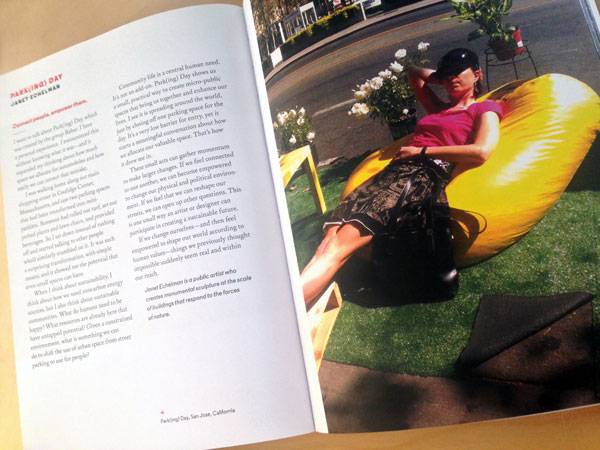

Inside Designed for the Future. Photo credit: Rachel Kruse

The Format

The format of this book makes it easy for the reader to digest information and know what to expect on the next page. Each project or idea is given a name (example: The High Line), followed by a designer (example: Jeff Shumaker.) Before the multi-paragraph project description, there is a tagline in red that grabs the reader’s attention (example: suspend disbelief and see the potential). With that information and a supporting image or collage of photos to the right, readers gain a quick understanding of the idea being presented. In the case of The High Line example, Jared Green explains the history of the project, tells how it came to fruition, speaks to the public-private partnerships that made the project a reality, and emphasizes how collaboration was influential in making the idea a reality.

Inside Designed for the Future. Photo credit: Rachel Kruse

About The Author

Jared Green may be a familiar name to landscape architects in the online publication realm, as he is the editor of “The Dirt,” a blog produced by the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). As Senior Communications Manager for ASLA, he researches, interviews, and writes on a variety of topics including apps for landscape architects, the impact of infrastructure and cities and general project reviews.

Inside Designed for the Future. Photo credit: Rachel Kruse

Why Should You Get This Book?

“Designed for the Future” is well written and easy to read, appealing to a wide variety of designers, both professionals and students. The ideas are refreshing, the information is specific without bogging down the reader with too much technical language, and the photos are eye catching. This would be a great book for a student in the design field or someone outside of the design world looking for an introduction to all that architects, landscape architects, urban planners, and environmentalists study. A comment about a specific project can be taken into a broader sense in saying that the goal of this book is to “form a new language of sustainability that is beautiful and legible to everyone.” If you love this book, check out these other book reviews:

- Drawing for Landscape Architecture

- Detail in Contemporary Landscape Architecture

- Visual Communications For Landscape Architecture

Pick up your copy of Designed for the Future today!

Review by Rachel Kruse Return to Homepage

5 Best Ways to Increase Biodiversity in Urban Landscapes

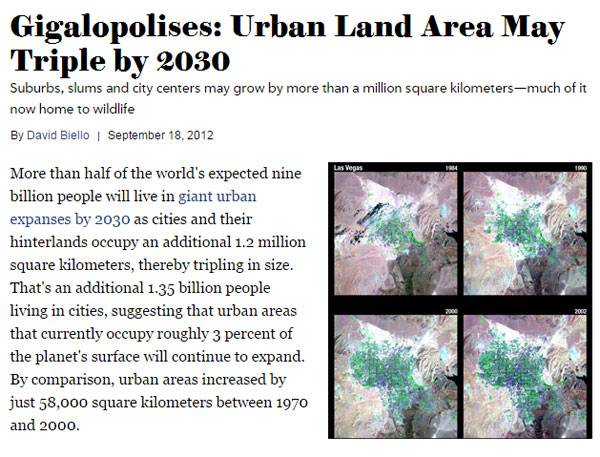

A look at 5 ways to increase biodiversity in urban landscapes and embrace nature into our designs. Biodiversity — the diversity of life in a habitat or ecosystem — is a sure sign of the health of that habitat or ecosystem. A diverse array of bacteria, insects, birds, mammals etc. makes a system more robust and able to withstand stress. Diversity, in this case, has a few layers; the number of varied species within an ecosystem, the number of individuals within a species and genetic diversity within the species (Rottle & Yocom). It means more than having lots of butterflies in the garden in spring; healthy biodiversity affects everything from the number of bees and pollinating birds, to compost-eating bacteria cycling nutrients, to having enough bats consuming metric tons of crop-eating insects. With urban areas predicted to triple in size by 2030 and natural habitats declining, it stands to reason that if urbanites don’t want ecological robustness to decline as well, biodiversity must be designed into urban landscapes. What’s in This Article:

- Provide Wildlife Corridors and Connections Between Green Spaces

- Use Organic Maintenance Methods and Cut Back On Lawns

- Use a Native Plant Palette and Plant Appropriately

- Utilize Existing Green Space Connections

- Be Mindful of Non-Native Predators

Urban areas predicted to triple in size by 2030. Image: Printscreen source

Here are 5 Ways to Increase Biodiversity in Urban Landscapes

1. Provide Wildlife Corridors and Connections Between Green Spaces

Providing options for wildlife to travel and find new food sources, water sources, and mates are extremely important to urban biodiversity. The hedgerow in England, for example, has been a part of the English Garden aesthetic for many hundreds of years. The bush or shrubbery provides a physical barrier for larger animals and people but allows for small animals to pass under, through, or along the roots of the hedgerow from garden to garden. Recently, though, with the increase in popularity of impassable fences lining garden boundaries, hedgehog populations in England have drastically dropped.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Using “soft engineering” techniques such as rain gardens and bioswales to handle stormwater is a good way to provide wildlife corridors. Native grasses, shrubs, and trees are most likely to thrive in rain gardens, which are relatively barrier-free. They also keep the wildlife out of the street and out from under tires.

Swale and Rain Garden in Traffic Triangle, near Bartrams Garden. Credit: Philadelphia Water Department, CC 2.0

2. Use Organic Maintenance Methods and Cut Back On Lawns

Urban biodiversity can be supported by avoiding chemical fertilizers and pesticides that are not picky and can’t tell the difference between good bugs and the bad. Bees, in particular, can be sensitive to pesticides, both organic, and chemical. Also, a shorn lawn doesn’t provide food or shelter for most wildlife, even down to the bacterial level if pesticides are liberally applied. More reasons to stop designing lawns can be found here.

Featured image in our hit article 8 Reasons to Stop Designing Lawns — and 2 Reasons to Keep Designing Them

3. Use a Native Plant Palette and Plant Appropriately

The locations of cities are not random; spaces were chosen for future urbanity for the same reason that many plants and animals colonized them first; proximity to the ocean, estuaries, major rivers, and land with enough nutrients to support diverse plant life. Because of this pre-existing relationship with the land, it’s easier to support those same species even now long after the estuary was dredged and the river straightened. With bones of a native ecosystem still buried under the concrete it’s easier to bring that system back to (certainly modified) life. Generally, planting natives is the best way to support a habitat’s natural wildlife because the birds and bugs are already built to eat and use them. Choosing location-appropriate plants ties into the fundamentals of good planting design. Though planting just natives alone won’t necessarily increase biodiversity to its fullest potential. It’s important to have an idea of how many and what kinds of species can be supported, as well as how many benefits a plant offers to the ecosystem. For example, a University of Delaware tree ranking found that native oaks support more than 500 different species of insects, while Gingko, a common choice for street trees, only supports three.

4. Utilize Existing Green Space Connections

Incorporating existing forest, wetlands, and even water retention ponds within a site or nearby space that likely already supports wildlife is a great jumping-off point for discovering what kind of diversity you should design for. The design team for Clos Layat Park in Lyon, France, did just this when incorporating an existing forest into the south side of its plan by continuing the forest into the park. They also included a meadow and dedicated a part of the park to a pollinator garden.

5. Be Mindful of Non-Native Predators

Housecats alone are responsible for between 1.4 billion and 3.7 billion songbird deaths each year. When designing in residential neighborhoods, keep in mind not just the problems local wildlife have in terms of habitat and food availability, but how likely it is that they will become food for non-native predators. Designing for biodiversity makes wildlife your client, and designing a space that lures your client to its death is a no-go. – Biodiversity in urban areas includes much more than rats and pigeons; we can decide how supportive to different kinds of life our urban spaces are rather than grudgingly accepting only the most adaptable species. What kinds of life would you like to see planned for in urban landscapes? How would it affect the way urbanity is planned? On what scale would you like to see it supported?

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Caitlin Lockhart Return to Homepage

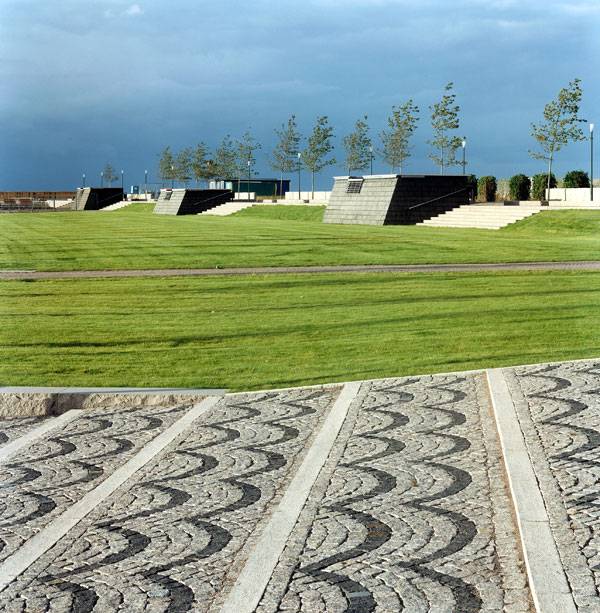

Pyramidal Topography Sculpts Community Common Park’s Iconic Presence

Community Common Park, by Janet Rosenberg & Studio, in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. When we hear the word pyramid, we instinctively associate it with Ancient Egypt, the Great Sphinx of Giza, pharaohs, or even mummies. And although our leading lady in this article isn’t Cleopatra, it doesn’t mean that the content you are going to read will be any less exciting. Imagine that instead of in Egypt, our story is set in Canada. The main characters are not pharaohs, but landscape architects. And the pyramids on which we will focus are not enormous and made of stone, but are much more welcoming, grassy, and — above all – designed for the community. Our story begins with the studio behind Community Common Park, continuing on to explore in detail the philosophy of the design. If you are eager to find out how the story ends, read on. What’s in This Article:

- Philosophy behind the project

- Elements of the design

- Inspiration behind the design

- Sustainable practices

- Full-size picture gallery

Community Common Park. Photo credit: Jeff McNeill Photography

Community Common Park

Engage-Excite-Enhance Design Philosophy

As one of the most outstanding landscape architecture and urban design firms in Canada, Janet Rosenberg & Studio has proven once again that it undeniably deserve its reputation. Imprinted with the passion for landscape architecture and design in communities, the team reveals its aspirations on its website: “We are creative thinkers who develop out-of-the-box solutions as a collaborative team. Drawing from individual strengths, we create treasured, ecologically responsible landscapes that respond to the demands of the urban environment, and engage, excite, and enhance the quality of life for those who inhabit them.” – https://www.jrala.ca/about/our-studio

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Community Common: 1.2 Hectares Designed for People

In their efforts to provide a park meeting the needs of Mississauga’s local community, the designers had to find a way to attract people. Because Community Common is a neighborhood park adjacent to several new condominium developments, it is designed to become a year-round center for public events, interactions, and cultural activities. “The goal behind our design of this park is to create a flexible and functional green space that can comfortably accommodate small and large groups of people,” the design team explains.

7 Main Park Elements

To satisfy the needs of visitors in the park, multiple passive and active recreation activities are provided. A multi-use sodded playing field invites park-goers to spend time resting, contemplating, or just wool-gathering undisturbed. The central social plaza, on the other hand, is the place for socializing, laughing, and enjoying the company of other people.

Community Common Park. Photo credit: Jeff McNeill Photography

Community Common Park. Photo credit: Jeff McNeill Photography

Influential Topography and Design

We already mentioned the green mounds, but don’t you think they deserve more attention? At first sight, they don’t seem exceptional. But is that right? The two pyramidal hills are arranged in the two opposite angles of the park’s area. In this way, they enclose and shape the center of the park, inciting visitors to gather there. The transition from buildings to the softscape is also designed with fine taste and flair. The combination of architecture, irregular grassy pyramids, and trees results in a completed, natural-looking, yet characteristic urban scape. Last but not least, we shouldn’t forget that the shape of pyramids has its symbolism and grandeur. Even used as grassy hills, the pyramidal topography of Community Common speaks for identity and significance. Certainly, this is one more flawless model for landscape architects displaying how a well-thought-out design influences people and interacts with them. Exquisite park furniture, a dramatic lighting scheme, and precision to the last detail make the park look just right – and ready for people to start falling in love with it.

Community Common Park. Photo credit: Jeff McNeill Photography

Four Sustainable Measures

Along with the other values of Community Common, its design stands out for its sustainable approach. In order to minimize stormwater runoff, the landscape architects gave the green light to the softscape. The area of the softscape significantly exceeds the hardscape’s range. The selection of native plants is also a well-known method of reducing maintenance costs. And the large-growing shade trees contribute to reducing the heat island effect and smog. Low-maintenance materials, as well as a designated dog area that ensures that waste is contained and lawns stay clean and unpolluted, are the last two ecological measures taken into account.

The Turning End of Community Common’s Story

After examining this project very closely, we can generalize Community Common’s story in just one sentence, as the designing team did: “Community Common Park is imbued with strong identity and iconic elements that will help to establish the new community within Mississauga’s downtown core.” In the end, it turns out that the main characters in this story aren’t the landscape architects, but the people; landscape architects are the supporting actors. Shouldn’t it always be that way? What moral can we draw from this story?

Full Project Credits for Community Common Park

Project Name: Community Common Park Landscape Architects: Janet Rosenberg & Studio Area: 1.2 hectares / 3 acres Budget: $3.2 million Client: City of Mississauga Timescale: 2008 – 2010 Services: LandscapeArchitecture Photography Credit: Jeff McNeill Photography Location: Mississauga, Ontario, Canada Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Velislava Valcheva

The Road to Success: Interview with Ph.D. Landscape Architect and Lecturer Veselin Rangelov

LAN writer Velislava Valcheva, gets the chance to interview Ph.D. Landscape Architect and Lecturer Veselin Rangelov. Why do we want to be successful? Is it because we want to prove to the world that we are capable of achievements or is it because we want to prove it to ourselves? Unfortunately, most of the time, neither is the answer. One huge part of why people want to be successful is just because everybody wants that. We have gotten used to the idea of success as something thoroughly positive and unilateral. But the truth is that there are two sides to every coin. And one of the sides of success’ coin is its price. So before you go chasing waterfalls, ask yourself, what does success mean to you? And will it bring you satisfaction? If you are willing to find out what a young but very experienced and talented landscape architect says about this topic, join our journey to success in this interview.

In this interview, we discuss the following:- Where it all began

- Obstacles to a strong career

- Seeking and giving help

- The difference between success and maintenance

- Starting out on your own

- Compromising with the client

- Juggling careers

- Dealing with economic difficulties

- Secret pleasures

- Recommended Books

- The secret to success

Veselin Rangelov

Veselin Rangelov is owner and founder of two design studios – LANDSCAPE PROJECT and URBAN SCAPE. He is based in Sofia, Bulgaria, but has extensive world travel experience, which has shaped his broad views that are enriched by multiple cultures. Rangelov is a versatile personality with a varied professional resume, who shares with us his insights about the road to success.

Photos of Veselin Rangelov’s work. Photo credit: Diana Petrova

[gmedia id=16]

Veselin Rangelov Interview

LAN: You have a fairly extensive professional experience. Where did your career begin and what advice would you give to young professionals and students who are at the beginning of theirs? Rangelov: In the final year of my studies, I started working as a designer at ALD-Karamochev architectural studio. That period was a very useful experience to me. On the one hand, I learned a lot about our profession from the practical point of view. On the other hand, I realized that I have an individual style and my way of looking at things doesn’t always coincide with those of others, but there is nothing wrong with that. I wanted to show the way I see things and that aspiration made me go on my own way and establish my first designers’ bureau – ACER DESIGN. LAN: What obstacles came in the way at the start of your career path? How did you overcome them? Rangelov: Undoubtedly, at the beginning it is most difficult to bring the theory and practice together. This is why I think I’ve got lucky at that time, starting my career at ALD-Karamochev. At this time, the design office was working on the most significant projects all over the country, and to me, every day there was like jumping in at the deep end. But one thing is for sure – I could always count on the support of the more experienced colleagues. I also remember that we spent 12 to 14 hours a day at the office, but we took our job as a challenge and had a lot of fun as well. LAN: Have you ever looked for help from more experienced professionals, or have you tried to deal with the difficulties in your development on your own? Do you help young colleagues pave their way for successful realization? Rangelov: Yes, at a regular basis. Even at present, I often consult with more experienced professionals and experts. I always accept with great interest the different point of view and believe that one learns while alive. The majority of my colleagues at the University of Forestry have tutored me, and to this day I have the same respect for them as before. We gladly discuss interesting topics and projects together. I’m glad that my students look at me the same way and that they often ask for my opinion on important issues. On the other hand, students are 20- to 22-year-old grownup people, who have with them the innovative thought of (a) young generation. This makes my contacts with them extremely useful to me, too. Very often, when we discuss some projects, I forget about the difference in our ages, and fill myself with their youthful enthusiasm — the one that makes the world go round. LAN: What is more difficult — the breakthrough at the beginning or to maintain the success after that? Rangelov: Actually, I don’t think that there is a universal formula for that. At least I have never looked at things that way. The sense of responsibility has always been most vital to me — to realize that you are responsible for the quality of the environment people live in. The key is to be satisfied with what you do. That’s when success comes and you realize that your work is admired by a wide range of people. And this is amazing, but quite obligatory at the same time. Life has taught me that success is something very imaginary – today it’s right in front of you, and tomorrow it can be gone. Things don’t always go in accordance with our expectations, but we have to believe deeply that after unsuccessful periods, the successful ones follow, and we will meet success again. It’s just that we shouldn’t lose our faith and persistence. LAN: It is assumed that at the starting point of their careers, young landscape architects have to hunt clients, and over time, the opposite happens: Clients become the ones who seek designers’ services. Does this rule apply to you, too? And is there a way in which this time interval can be reduced to a minimum? Rangelov: I can tell with certainty that a lot of patience is required. A good designer has to walk the walk. I started working as a laborer at building sites in the second year of my studies. I used to go working on weekends and holidays – not because of the low daily wage, but mostly on account of my desire to learn more about how to build such sites. After that, I worked as a designer at an architectural office, and later, we formed our own design office with colleagues. In the meantime, I started working as an assistant at the University of Forestry, and then I became a lecturer at the University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy. Today, I’m the owner of two design studios – LANDSCAPE PROJECT (for landscape architecture and design) and URBAN SCAPE (for consultancy in the field of spatial and urban planning). I will hardly stop up to here — life is a string of changes and many different opportunities, of course. I always advise young colleagues not to hurry. Take your time to experiment – this is how you will find the perfect place for you. And believe me, this will reflect amazingly on the quality of your work, which won’t go unnoticed. LAN: Certainly, there are cases in which you have to compromise with your design philosophies because of clients’ demands. How far should a designer go in his or her conformity in order to be able to preserve his/her reputation? Rangelov: Indeed, a designer’s role is very delicate, as he/she is the one who has to embody the rough ideas of the assignor and, finally, to get a result which is remarkable and exciting. I have often come across situations in which that seemed to me unattainable, but, in fact, very often it is these situations that provoke unconventional thinking, and the final result turns out to be surprisingly good. It is good to show tact, and compromises should be mutual, as well. Compromises should be between you and the investor, but in any case, no compromise should be made with the principles of design. LAN: Besides being a landscape architect, you are also a lecturer at the University of Forestry in Sofia and a member of the managing committee at the Chamber of architects in Bulgaria. These are three entirely different fields of work, with various responsibilities. How do you manage to coordinate them? Which one is of greatest importance to you and why? Rangelov: These different activities are united by one common theme and, at the same time, they differ enough for a person to devote to each one of them individually. Sometimes I ask myself, how did I get here? Do I really need so many engagements? And how would I feel if I had just one of them? When I come to think, however, I realize that I have the same passion for each one of them. Maybe those three works best express my desire for change for the better. And even though I take too personally each one of them, when they ask me what my profession is, I reply unconsciously – a lecturer – probably because being a lecturer seems most responsible to me. I always mind what I tell to my students, as my mission is to hand down knowledge impartially, without imposing my stereotype and model of thinking. LAN: In a small Eastern European country like Bulgaria, there are many obstacles related to the financial crisis, the insufficient demand for landscaping services, and the delayed development of landscape architecture as a whole. What is the price of being one of the most successful landscape architects in Bulgaria? Rangelov: It is true that today people live a difficult life in Bulgaria. It is also true that landscape architecture isn’t always on the agenda. Despite that, I’m trying to change this stereotype. I won’t get tired with claiming that creating high-quality urban environment, which provides recreation for adults and habituates adolescents to aesthetic principles, is amongst the top priorities. I have no doubt that better times will come for our beautiful country, but this will happen only if we keep our value system, our self-confidence, and our self-esteem, for which the quality of our environment has a major importance, to a great extent. Unfortunately, the difficult period of political transition led to a collapse in the attitude to institutions and authorities. In Bulgaria, everyone understands everything, and that presumption can be seen clearly in the quality of our urban spaces. I hope for people to realize as soon as possible that everything requires a certain professional, not a layman, saying he/she understands everything. LAN: Despite all the hardships, what brings you the biggest satisfaction of being a landscape architect? Rangelov: Undoubtedly, the work with live “building” material. The satisfaction to create something that lives and develops is enormous. Moreover, it constantly changes its appearance and develops its potential through time. The best moment comes when you walk through the park you designed and see the smiles on people’s faces, not implying that you are the author of the landscape. LAN: Which three books would you recommend for those who want to follow in your footsteps? Rangelov: If it’s not necessary to name books directly related to landscape architecture, I would recommend all the books written by André Maurois. I love that author, and his books are real life lessons. But if I have to mention a book in our professional field, I would recommend to my students the books and the textbooks of Professor Ivan Nikiforov, in particular “Synthesis of Arts in Interior and Urban Spaces” and “Streets and Squares”, which undoubtedly had a tremendous influence on my views. LAN: After all, is there a shortcut to success? Rangelov: I will say it one more time: Success is something too imaginary and it shouldn’t be leading in our career path. Indisputably, it is great to reach it, but the purpose has to be the responsible attitude to what we do. LAN: You are a role model for many young people. What directions would you give to them to remember on their way to success? Rangelov: Truth be told, it took me some time to realize that even unconsciously, every teacher — less or more — is a role model to their students. This is a great responsibility. I have always tried to be a positive example and to support young colleagues, as they mostly need someone to encourage them at the beginning. I have always told them not to be afraid to make their steps. These steps can be small, but they have to be done. Some make big steps and often happens to them to stumble, but this is a part of life. You stand up, draw the necessary conclusions, and keep moving on more confidently. There is no need of rushing – it is more crucial not to miss the details in the haste. This is how you will never stop learning, and believe me, when I say that, this is amazing. – LAN: Thank you, Veselin Rangelov, for sharing with us your valuable directions and knowledge on the question of success. It was a great pleasure for me to conduct this interview, and I wish that you never stop inspiring others, because people need idols like you. In conclusion, we recall the words of Andre Maurois, who says that, “Nothing belongs to us except our time.” So make sure you spend your time wisely, and go seize YOUR day. You can find more information about Veselin Rangelov’s projects at: www.landscapeproject.eu

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Interview conducted by By Velislava Valcheva Return to Homepage

How Mathildeplein Creates a Green Oasis in the City

Mathildeplein, by Buro Lubbers, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. In urban environments, there is a constant battle between the need for functional public space and the social desire for intimate, semi-private spaces. Living and working in the city sounds like the ideal economic and sustainable solution, but the reality often fails to provide spaces that connect with human scale and the natural environment. Buro Lubbers aimed to address this issue through his design of Mathildeplein by providing a square that connects to the public realm while creating a green and intimate semi-public space. Mathildeplein occurs at an important traffic junction in the heart of Eindhoven, beneath the iconic Light Tower. The Light Tower is a striking building that was formerly home to the Phillips factory; its distinctive seven-sided form and large windows have become a symbol of the city. In the late 19th century, the Phillips factory moved production to other premises and the building faced demolition.

View The Full Gallery for Mathildeplein

[gmedia id=14]

Mathildeplein

However, protests to protect the building led to it becoming a historical monument. Renovation began in 2000 to convert it into residential units, a gym, a restaurant, and a hotel. With this renovation came the need to provide residents with outdoor space, and so Buro Lubbers was appointed to bring life into an otherwise hard urban space.

Mathildeplein. Photo courtesy of Buro Lubbers.

A Green Enclave

The concept for the square was to create a tranquil green space where people could relax away from the urban frenzy. This concept was limited by a number of technical restrictions, as well as the need to maintain the focus on the Light Tower. The first of these restrictions was the fact that the square was actually a roof garden, sitting above a two-story parking garage.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

This meant that there was no possibility for large amounts of planting, resulting in the need to plant within large planter boxes. The location of the square within the transportation hub also meant that large portions of the space had to be kept clear for emergency services. Furthermore, the top of the parking garage sat 650 mm above the level of the street, forcing the square to become physically separated from its surroundings.

Concept Driving by Technical Restrictions

Buro Lubbers took these restrictions and translated them into a strict, linear plan consisting of planter boxes of various lengths, widths, and heights. These planter boxes correspond to the structural weight restrictions on the parking garage roof, allowing structure to dictate the form and placement of the boxes.

Mathildeplein. Photo courtesy of Buro Lubbers.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Is This The End Of Landscape Architecture?

Does landscape architecture need to die so that we can see the birth of a complete profession? Now more than ever, landscape architecture is both highly visible and influential. Many circles now see the discipline as usurping architecture in terms of its ability to catalyze urban form. This cultural shift — fostered largely by a growing public awareness of the benefits of a quality urban realm, a reading of the city as landscape, and an admittance among design professions that landscape architects are today most appropriate to respond to this condition — brings forth questions about the future of the profession. But what if landscape architecture was to be no more? I speculate a different future — one that witnesses the marriage of landscape architect and architect into a singular, all-inclusive design discipline. Visions for the future of the Anthropocene and the contemporary city writ large need to meet the demands of population increase, coupled with a decrease in habitable and arable land, and critical resources of air, water, food, and raw materials. By necessity, we must learn to better imbricate edifice and environment. The result would be genuine sustainability — a word that today has lost much of its meaning, but whose tenet is forcing architecture and landscape architecture to coalesce.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

A Melting Pot of Design Professions Under One Roof

Rather than the dichotomizing of building/landscape that often leads to hermetically sealed practices (not to mention gaudy buildings sited in terrain like foreign objects and lacking any meaningful dialogue with existing locales), myriad practices today now possess a melangé of design professions under one roof. This amalgam of architecture, interior architecture, and landscape architecture can lead to hybridization, innovation, and fertile approaches to constructing the world we inhabit. What would this amalgamation of professions look like? Kim Wilkie, a British landscape architect and Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, cogitates a “return to the 18th century concept of architect in a complete role”[1], wherein the conventionally accepted confines of 20th century professional design roles are rearranged or, in the case of some recent built work around the world, almost reversed.

Remembering The Experts

Eighteenth-century designers such as Sir John Vanbrugh (1664–1726) and William Kent (1685–1748), for example, worked as both architects and landscape designers. Kent is considered a father figure of modern landscape gardening who “leaped the fence and saw that all nature was a garden”[2]. He lacked a classical education but nonetheless possessed deft craftsmanship in not only architecture and landscape design, but also in painting and theater set design.[3] The famed Rousham Gardens, in Oxfordshire, attest to this and are some of Kent’s superlative landscape design work. Many of his other landscapes were designed to complement his own architectural work.[4]

Bluff Creek and the new Playa Vista residential development on the Ballona wetlands, in Los Angeles, California. The Hollywood Hills, and behind them, the Verdugo Mountains, are seen in the distance. Photo credit: Downtowngal. Licensed under CC-SA 4.0, 3.0, 2.5, 2.0 and 1.0. Image source.

Playa Vista Central Park on Los Angeles

If we fast-forward to the present day, we again see this admixture. Sometimes referred to as “earthi-tecture”, this is no anomalous act. Completed in 2010, Playa Vista Central Park on Los Angeles’ West Side is an eight-acre slice of urban infrastructure designed by architect Michael Maltzan in collaboration with landscape architect James Burnett from Houston and Boston-based firm The Office of James Burnett. The design emphasizes architectural forms and textures through selective plant matter and materials, reinforcing the spatial experiences within the park and blurring the lines between the two disciplines. Another of noteworthy precedence is the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust by Belzberg Architects. Submerged into the terrain of Pan Pacific Park, the museum is understood as a continuous, topologically formed structure through the blending of concrete and vegetal hues and textures with those already in existence in the park, extending them onto the building and thus muddling the line between environment and edifice. This overlap is, however, not a new phenomenon. Rem Koolhaas, the esteemed Dutch urbanist and architect, has long prompted dissolution of traditionally established terminologies in favor of reading the urban territory as interconnected landscape tissue.[5] Along with Koolhaas, stalwart urban designers such as Adriaan Geuze of West 8 and Zaha Hadid of Zaha Hadid Architects, for example, have for years repudiated any inelastic hierarchies around architecture, landscape, and infrastructure.[6] In their work, they explore both the architecturalization of landscape and the landscapification of architecture.

Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust Designed by Belzberg Architects. Photo credit: Belzarch. Licensed under CC-SA 3.0. Image source.

References

1. Wilkie, K. The Future of Landscape Architecture. 2000; Available from: https://www.kimwilkie.com/talks/the-future-of-landscape-architecture/. 2. Walpole, H., The History of the Modern Taste in Gardening, ed. John D. Hunt (New York: Ursus, 1995). 22: p. 313. 3. Rogers, E.B., Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History. Vol. 486. 2001: Harry N. Abrams New York. 4. Allain, Y.-M. and J. Christiany, L’art des jardins en Europe. 2006, Citadelle at Mazenot, Paris. p. 280. 5. Koolhaas, R., et al., Politics-Poetics Documenta X, The Book. 1997: Germany: Cantz Verlag. 6. Angélil, M. and A. Klingmann, Hybride Morphologien: Infrastruktur, Architektur, Landschaft. Daidalos, 1999. 73(10): p. 16-24.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Paul McAtomney

Etele Square Removes the Roof to Create Hungary’s Biggest Outdoor Waiting Hall

Etele Square, by Ujirany / New Directions, in Budapest, Hungary. Waiting for a train and it’s delayed again. Sitting in the waiting hall, counting the seconds, and suddenly finding yourself in awe of the market art on the seats. Or perhaps you’re just sitting there counting the tiles on the floor. The wait seems to be never-ending, and you’re feeling as if the boredom couldn’t get any worse. Sound familiar? Then you are probably a commuter and, just like me, you have seen plenty of waiting halls in your life. They are all pretty much the same: tall and noisy, with gray walls and chairs that are rather uninviting. As a commuter myself, waiting for buses, trains, or trams has become a monotonous and sometimes unbelievably boring routine, more or less due to the places where I have to wait. But have you ever wondered what the waiting hall would look if it was taken … outside? Do waiting halls always have to be indoors? Could they be placed outdoors?

Etele Square. Photo credit: Ujirany / New Directions, Tamás Bujnovszky. See the Full Gallery on Page 2

Let’s have a look at Etele Square

Located in the heart of Hungary’s capital, Budapest, Etele Square takes urban landscape design to a whole new level by moving the qualities of an indoor space outside. The designers responsible for this twist are Ujirany / New Direction. The designers rearranged the space in such a way that people waiting for the metro or bus can choose to wait outside, simply by enlarging the space and removing the roof of what has already been functioning for years — the indoor waiting hall. Thousands of people walk by Etele Square every day, thanks to its proximity to the metro and bus stations. The square is a connecting feature between the two buildings and, after the transformation it has undergone, not only serves as a park for the nearby living areas but also as an enormous waiting hall for the two stations.

Etele Square. Photo credit: Ujirany / New Directions, Tamás Bujnovszky. See the Full Gallery on Page 2

Square Meadow

Strictly based on its regular, square-shaped features, Etele Square shines a completely new light on geometric shapes in urban spaces. If you imagined a space of 7,682 square meters covered in chess-like combinations of planting and paving, you would think that the square would seem monotonous and unexciting. But that is not the case. The square system organizes the whole space, rather than defining it. The strict pattern of the pathways is broken up by grassy vegetation squares, filled with two different species of grass. Planted in such a way as to create a linear effect, the grasses are meant to continue the striped pattern of the black and white pavement surrounding them. When seen from a distance, this use of planting may look as if it was an “uninterrupted” regular meadow in the middle of a city, but as soon as you walk closer, you realize the meadow is actually made up of separate squares. This technique also allows users to take limitless routes around the square.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

The striped effect is continued vertically through the use of columnar trees planted around the square. The use of perpendicular lines optically encloses the whole square, giving the impression that the space is much smaller (and thus more comfortable to look at and be in) than it actually is.

Etele Square. Photo credit: Ujirany / New Directions, Tamás Bujnovszky. See the Full Gallery on Page 2

Living Corridors

The use of color here is not accidental — the combination of colors reduces the monumentality of the square. Picture the square as a big room in your houses, rather than as an outdoor space: The black and white of the paving gives the impression of walking on a carpet, and the contrasting green grasses are like the walls. Combined, the “carpets” and “walls” make a strong impression of walking along several corridors, rather than being overwhelmed by the vastness of the space. Because the space is an outdoor waiting hall, the designers had to think of resting areas for the people using the square. Turned backward to the grassy squares, we can find plenty of seating located along the pathways – all easily accessible and visible, but at the same time offering a little bit of privacy…

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

How Baan San Ngam Takes its Inspiration From Nature

Baan San Ngam, a low-rise condominium project by Shma, in Hua Hin, Thailand. A subtle yet inspiring landscape design concept, Baan San Ngam appears as a fluent project that creates a vibrant natural environment, rich on experiences, harmonious, and respectful of Mother Nature. Situated in the Prachuabkirikhan province of Thailand and facing the seascape, the 20,753-square-meter site is known for its mangroves, which provide a natural wildlife habitat that frames the mountain scene in the background. The design of this mesmerizing project optimizes the interplay among six different ecological elements: Sea, dunes, swamp, swale, mound, and forest. It is a combination that gives visitors a variety of experiences as they step up or down into different levels, distinguished by various textures transitioning from the vegetable to the mineral. Therefore, the concept of “Nature vs. Art” explores a new syncretic balance among different shapes, colors, shades, textures, and rhythm — allowing, at the same time, the development of natural surroundings.

Baan San Ngam

Following this conceptual design work, Shma has drawn an organic form of a swimming pool area in between buildings to recreate the natural flow of the sea. A visual and physical linear axis was created to connect the swimming pool’s movement to an open overlook toward the sea. Shma’s design relies on interesting shapes and attention to detail. Indeed, some new small grass dunes were adjusted to the landscape in order to create a spatial coherence in the design and to offer the possibility to introduce new activities to residents.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

As for the slant of the top edges of the swimming pool, these were designed for both functional and aesthetic reasons. The edges help water to run off slowly without being collected on the sides of the pool. The inviting atmosphere was created through the pockets of sunken seating spaces below the water level and were placed inside the swimming pool, a design that mimics a bird’s nest and provides areas for more rest and relaxation.

Baan San Ngam. Photo credit: Pirak Anurakyawachon

Harmony and Contrast of Materials

All the materials were chosen to give a strong visual focus on the landscape and to remain harmonious with the environment. Different colors and textures were used to cover and to draw fluent patterns on the ground, going from light to dark shades and in between, creating a powerful sense of energy with contrasting materials such as sandwash, concrete, gravel, and wood. “We use sandwash as ground covers around the pool area because sandwash is a material which can be designed and create patterns easily. A variety of colors and shades can also be chosen. The hardscape of Baan San Ngam is designed to be linked with the flow of the water and integrate well with the natural environment,” Shma explains. The ground’s texture is perfectly matched with the surrounding building’s façades, which makes it seamlessly blend with the whole landscape design. The landscape designers haven’t neglected the architectural side of the project — actually, they have kept an optimum green connection between the inside and the outside. For that, they have designed the swimming pool in a way to be accessible by all rooms on the ground floor. One might think that it is a floating island, but on a smaller scale. As for the rooms on the upper level, the landscape view was emphasized by the addition of tall plants.

Baan San Ngam. Photo credit: Pirak Anurakyawachon

About the Plant Choice

The designers were very meticulous about choosing the types of plants for each of the six ecological elements, with the objective of relating the plantings to the local environment without interrupting the landscape continuum. For example, the dune area was planted with thick and large leaves, because they remain durable in the face of wind and sea breeze. Luscious, green plants were selected for the swamp area. The swale area was planted with colorful flowers, trees, and ground cover. In the mound area, designers opted for ground cover plants with small, delicate leaves. And for the forest area, big, tall trees were planted to provide a natural protection barrier and to accentuate the forest aspect.

Baan San Ngam. Photo credit: Pirak Anurakyawachon

Full Project Credits for Baan San Ngam

Name of Project: Baan San Ngam Landscape Architect: Shma Company Limited Design Director: Yossapon Boonsom Landscape Architect: Yossit Poonprasit Horticulturist: Wimonporn Chaiyathet Client and Developer: Sansiri PCL Architect: Somdoon Architects Site Area: 20,573 square meters Period of Design/Construction: 2012-2014 Location: Hua Hin, Thailand Landscape Budget: 23 Million Baht Facebook: Shmadesigns M&E: V6 Group C&S Engineering: ACTEC Construction Project Type: Low Rise Condominium Completion Year: 2014 Photograph Credit: Pirak Anurakyawachon Landscape Budget: 23 Million Baht Lightning Budget: 2 Million Bath

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Naila Salhi

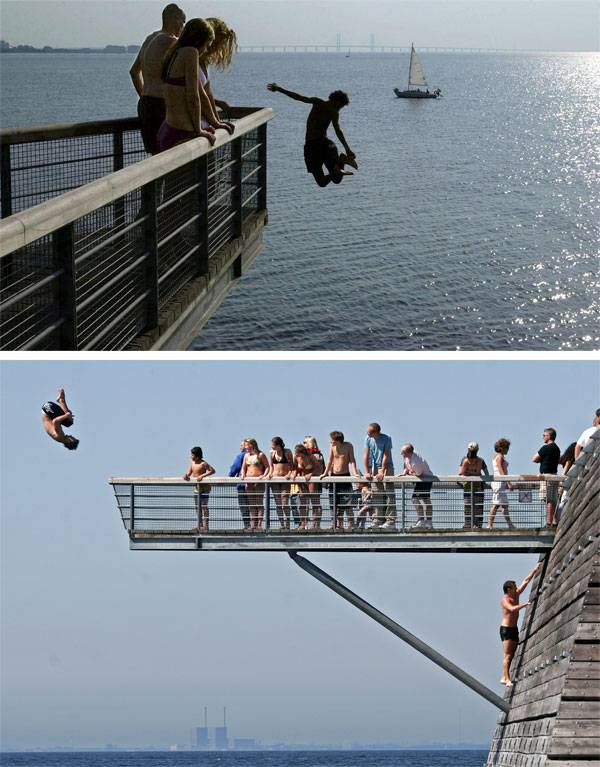

Dania Park, Landscape Architecture’s Love Story With Water

Dania Park, by Thorbjörn Andersson and Sweco Architects, in Malmö, Sweden. Water is an excellent source of inspiration for the field of landscape architecture and the present project does not make an exception from this rule. This waterfront park was opened in 2001, bearing the trademark signature of Thorbjörn Andersson and having quite the perfect location – the edge of the Öresund strait, dividing the countries of Sweden and Denmark. Whenever we read about a new landscape architecture project, it is practically impossible not to be impressed with the amazing transformation that has occurred along the way. This situation is even more valid when it comes to Dania Park, as the area chosen for this project was part of the former Western Harbour, an industrial sector located on the Malmö coastline.

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Dania Park

The transformation project was ambitious to say the least, but the creative minds at Thorbjörn Andersson have managed to take it where it should be. The site went from a barren landfill, with contaminated mud to an amazing waterfront park, serving as a source of inspiration for future landscape architecture projects.

Inspiration Always Comes From Unexpected Sources

One of the biggest challenges that this project has presented was the identification of the site qualities. The designers gladly accepted this challenge and found their inspiration in aspects that are genuinely unique. Going beyond what serves in general as a source of inspiration, they saw that the site had a unique light and splendid horizons, with long views. In an almost poetic manner, three romantic elements have been used to create this amazing waterfront park, meaning the sea, the wind, and the sky.

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Dania Park. Photo credit: Alfred Persson

Integrating Spectacular Sunsets

Taking the inspiration to a completely new level, the project brought certain elements of nature closed to the visitors of the park. One finally had a place to enjoy the water waves, not to mention the spectacular sunsets on a lazy summer’s day. Nature remained a source of inspiration throughout the entire duration of the design process, the coastal landscape clearly being reflected into the making of the park. Variety was one of the objectives of the project and it was successfully achieved, with each season bringing a completely different experience to the park visitors.

Features of the Park Bringing the Elements of Water Closer to the Visitors

Among the principal features of the park, you can find the Scouts. These are actually three tilted concrete planes, penetrating the rough boulder lining. What are the best things about these features? Well, they allow the visitors of the park to reach the sea, enjoying the beauty of water and everything else that it has to offer.

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Embracing the Elements to Make Better Landscapes

In order for the visitors of the park to come even more in contact with the elements of nature, the designers of the project have added the Bastion. This is a 40 by 40 meter flat table, elevated at approximately 6 meters above the sea. The visitors can take delight in the elements of nature, including the wind and the splendid sunsets. Add to that the three wooden boxes (Balconies) that overlook the grass meadow (the Lawn) and you have the complete picture.

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Dania Park. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

“No water, no life. No blue, no green”. -Sylvia Earle

The above quote is quite representative for this project. As we take a good look at the features of the park, it is practically impossible not to notice how all of them turn towards the sea. All the activities of the park are connected in some way or the other with the water and the coastal landscape is splendidly reflected throughout the entire park.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

The Art of Creating a Legend AutoCAD Tutorial

The Art of Creating a Legend AutoCAD Tutorial from our resident AutoCAD expert UrbanLISP. Creating a design is a process. It is highly recommended that you create a backup of your AutoCAD drawings every time you make a significant change in the design. This will allow you to revert back to a previous version in case the latest changes don’t seem to work out that well. At the end of the process, you shouldn’t be surprised to have up to 30 backups of your file. Needless to say, you will have spent a lot of time and effort. If you drew it properly, you know the meaning of every layer, block, and line. But then it is time to present it. And guess what? The people to whom you present the plan don’t know it as well as you do. They need a legend! Drawing in any CAD program requires consistency, as mentioned in the article ’10 must do’s to become a professional AutoCAD user’. If you are consistent, you will have proper layer and block names and have placed every entity on the layer where it should be. You likely worked right up until the deadline to present it – which doesn’t leave much time to create a legend.

Creating a Legend AutoCAD Tutorial

Creating a legend can be tedious, because you know every little detail of the drawing already. But with the UrbanLISP ‘Quick Legend’ command, you can create one with just a few clicks. Like most CAD tools, it allows you to do something quickly. The end result is completely up to you. Before creating a legend, it is good to think about what should be in it. In order to determine what should be in it, it is good to realize that a plan drawing can be broken down into a few basic elements. Areas The most important elements of a plan drawing are areas. In AutoCAD, the areas can be defined by hatches. The hatches are the definition of each area, and together fill your entire plan drawing. The hatches will tell where grass, roads, bicycle paths, water, and slopes are. Objects In those areas are objects, and it is advisable to draw them as blocks in AutoCAD. Think of benches, lighting fixtures, drains, and bollards. When you insert them as blocks, you can move and copy them as one element. When you change the blocks, you change all of the blocks in your drawing. Linear Entities Lines, arcs, circles, polylines, splines, and ellipses are linear entities in AutoCAD. You can use them to draw a fence, a road axis, or utility lines. See these AutoCAD tutorials:

Creating a legend can be tedious, because you know every little detail of the drawing already. But with the UrbanLISP ‘Quick Legend’ command, you can create one with just a few clicks. Like most CAD tools, it allows you to do something quickly. The end result is completely up to you. Before creating a legend, it is good to think about what should be in it. In order to determine what should be in it, it is good to realize that a plan drawing can be broken down into a few basic elements. Areas The most important elements of a plan drawing are areas. In AutoCAD, the areas can be defined by hatches. The hatches are the definition of each area, and together fill your entire plan drawing. The hatches will tell where grass, roads, bicycle paths, water, and slopes are. Objects In those areas are objects, and it is advisable to draw them as blocks in AutoCAD. Think of benches, lighting fixtures, drains, and bollards. When you insert them as blocks, you can move and copy them as one element. When you change the blocks, you change all of the blocks in your drawing. Linear Entities Lines, arcs, circles, polylines, splines, and ellipses are linear entities in AutoCAD. You can use them to draw a fence, a road axis, or utility lines. See these AutoCAD tutorials:

- 4 AutoCAD Commands to Draw Paving Patterns on Curving Paths

- How to Show Topography in your Plan Drawing in AutoCAD

- How to Place Large Quantities of Trees in a Master Plan Instantly with AutoCAD

The Gray Area Although adding a legend is often the last thing you do for a project, it is good to keep it in mind as you go through the design process. When setting up plan drawings, you will see that 80 percent of the basis is the same. But there are always exceptions. Take shrubs, for instance. For one project, you might want to define an area with shrubs. For the next, you might have a particular specie in mind and have a nice block for it. Or take a fence. In one plan drawing, you might want to draw it as a linear object; in the next, you might actually design a fence element and want to place it along that line. And what about utility lines? You may have detailed information about where the sewer, electricity, water, and gas lines are and have a specific line type assigned to each one. For another project, you may not have such detailed information, but know roughly where they go. Then, all of a sudden it becomes a zone, an area. Important Side Notes When you create a plan, think about the elements you want to use to build it. If you are in doubt, ask yourself the question: How do I want to quantify it? In the example of the fence, if you designed your own fence, you will want to know how much of the element you have used. If you only know where it should go, you may just want to know the total length and, in that case, draw it as a linear entity. And how do want to draw kerbs? You can draw them as a polyline with the desired width so you know the length you need. Or you can draw them as elements so you know how many elements you need. Or draw them as an area, because polylines with a width have their downsides and using blocks is too detailed. Then you know the area. When you divide the area by the width, you have the total length. When you divide the total length by the length of an element, you know the number of elements. So there are several ways to go about it. Consider the scale of the drawing and the size of your project and you may find your answer.

WATCH: Make Your Dawing a Legend AutoCAD Tutorial

Creating a legend might seem tedious, but it can also be helpful in building your plan drawing. It will certainly help you to explain the plan to your clients or teachers. The ‘Quick Legend’ command can help you to compile the legend. You can find it in the UrbanLISP app store; as long as it’s stamped with the social download stamp, it can be downloaded for free. Download it now and become a legend at creating legends.

Recommended Reading:

- Digital Drawing for Landscape Architecture by Bradley Cantrell

- Detail in Contemporary Landscape Architecture by Virginia McLeod

Article by Rob Koningen

You can see more of Rob’s work at UrbanLISP

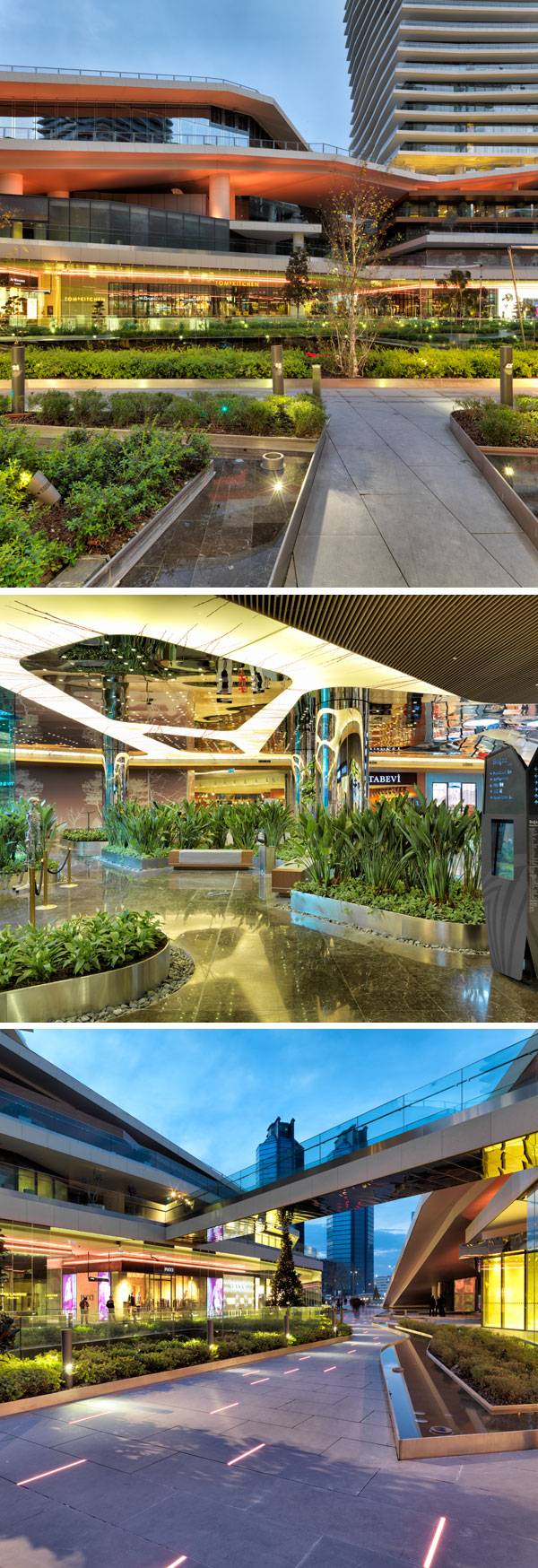

How Landscape Design Became the Most Important Feature of Zorlu Center

Zorlu Center, by DS Architecture – Landscape, Istanbul, Turkey. Istanbul is a dynamic city in a world of diversity. In light of continuous development, new innovative projects have to deal with the difficulty of harmonization and integration in old structures. In a city between two continents, Zorlu Center unites the historical Old City atmosphere with a futuristic flair of four towers through landscape design. Located in Levent, a business and urban milieu in Istanbul, the private investment project shows a multifaceted use and the variegated benefits of the landscape elements designed by DS Architecture – Landscape. Furthermore, in a context where the controversial issue of shopping malls and public life is becoming more criticized, Zorlu Center tries a new interpretation of this topic by creating alternative urban areas for Istanbul.

Zorlu Center Masterplan. Image courtesy of DS Architecture – Landscape

Zorlu Center

Although there are some main landscape elements, the multiple uses of landscape design are central for Zorlu Center: It’s the signature feature. Keeping the aspect of landscape diversity in mind and implementing it in further projects will turn out to be a formula for success and popularity. Let’s see the different aspects of Zorlu Center, where landscape design has become the most important feature. On the project site, residents, tourists, and workers can find a 100,000-square-meter designed landscape area. Zorlu Center promises a new social experience by embedding the idea of a shopping mall in a new kind of nature. The direct connection to the subway points to the strong infrastructural relation with the existing urban landscape. Being close to a high-traffic bridge and highways, the whole planting design contributes not only to the landscape of Istanbul and for recreation, but also serves as an herbal filter to the drawbacks of those roads.

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

A New Meeting Place for the People of the City

In the middle of Zorlu Center, DS Architecture – Landscape designed a new meeting place for the city in the form of a square, where water plays a major part. The planting consists of a successful combination of shrubs, native trees, and seasonal flowers. The wooden benches invite people to take a shopping or work break and relax in the heart of the site. In the extension of the main square, the courtyard allows alternating functions and flexible uses, and is characterized by the well-known plant of Istanbul: Pinus Pinea.

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Something for Everyone

Zorlu Center also has a multifunctional recreation area, with a swimming pool and a well-known children’ club — a playground where imagination comes to play. Furthermore, the facades of some of the buildings open into private gardens. Opened for a larger public, the Valley Park represents as a garden collection the themes of Istanbul and is a very valuable acquisition of the project.

The Shell – A Green and Tangible Utopia

Even if the landscape design is an integral part of the whole project, the most important element is the landscape roof – named “The Shell”. Beside other examples of green extensions, the utopia and imagination of vast green roofs becomes reality once again. Generally seen, landscape roofs are used for regaining lost green spaces on the ground (among other important benefits of green roofs).

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Planting at Zorlu Center

The green shell surrounds the structure and associates with the hill of Istanbul, reminding visitors that this was once used as recreation areas of the city. Covered mainly just by lawn but also by shrubs (eg. Lavandula Angustifolia, Ceanothus Thysflorus), trees (eg. Ginko Biloba, Olea Europa) and perennials (eg. Acanthus Mollis, Festuca Glauca), the shell offers an excellent Bosphorus and city view. It invites its users to recreate and to contemplate the tableau of Istanbul’s strait.

Who Has Access in Zorlu Center?

Some of the elements – the square, the park, and the courtyard – point to an openness and a public sphere, inviting everyone to make use of the multiple recreation opportunities. Nevertheless, sometimes appearances are deceitful. Being a private investment, all of the outdoor spaces are not public, but are rather semi-public areas.

Not Everyone is Welcome

That means that not everyone is equally welcome on the site. This contradicts with the wish of integration in the city fabric, which is not only physically constructed but also socially created. This issue is considered as being controversial and is an unfavorable aspect of private investments such as shopping malls and bureaus.

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Zorlu Center. Photo credit: Cemal Emden

Full Project Credits for Zorlu Center

Project: Zorlu Center Client: EAA + Tabanlıoğlu Project type: Mixeduse Project (retail, housing, office, recreational, commercial, cultural center, hotel) Investor: Zorlu Real Estate Development Architectural Project: Emre Arolat architects & Tabanlıoğlu Architects Landscape Project: DS Architecture – Landscape Landscape Architect of Record/Firm: Deniz Aslan / DS Architecture – Landscape Lead designer: Elif Çelik Design Team: Saime Selda İpek, Deniz Tümerdem, Zeynep Emektar Deniz Subaşı, Doğan Onur Araz Scope: Landscape Project + Application consultancy Project Location: Levent / Istanbul / Turkey Area: Site:12.840 m² / Construction Site: 91.868 m² Project Year: 2009 – 2013 Photography Credit: Cemal Emden Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Ruth Coman