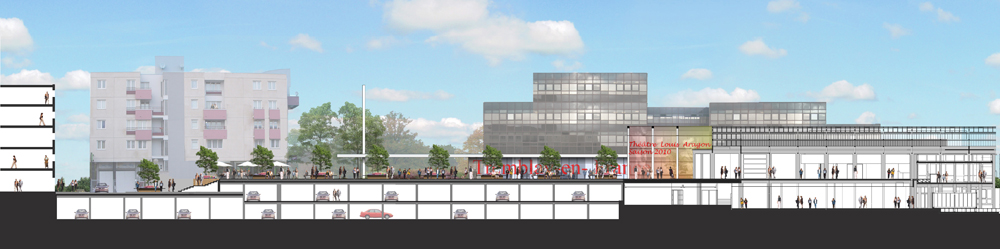

We take a look at how the Place des Droits de l’Homme project brought people back to a space that was forgotten about, rejected by time and life. The square, Place des Droits de l’Homme, is located in Tremblay en France. The town is a commune in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris, it has an area of 22.44 Km2 and is 19.7 Km from the center of the capital city; using public transportation, it would be a 1-2-hour trip. The square has a strategic location and has existed since the 70’s; it is surrounded by the town hall, the cultural center, the municipal library and housing, and it is the cover for an underground parking lot. The square has always been viewed as an essential piece of the city center but as time passed the space became neglected and forgotten, slowly becoming a mournful space, disconnected from the city.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

Place des Droits de l’Homme

The Conflicts

The square was having conflicts in achieving a strong and good connection between the city and the citizens, because it didn’t have a fluid connection with its surrounding space. The fact that it is 2 meters above the natural ground level was one of the reasons, plus there were elements such as misplaced urban furniture that acted as obstacles which increased the problem; those fringes reinforced the isolation of the square.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

These physical barriers needed to be softened because it also created an un-friendly scenario for people with reduced physical mobility. Another not-so-helpful characteristic was the square’s floor, it was a paving slab system that consisted of paving slabs over pedestals, sitting above a weatherproofing membrane. This system was really fragile, as it only permitted a maximum of 350 Kg/m2, limiting the versatility of the square, discouraging the presence of temporary markets or other uses; it also created difficulty for placing vegetation, plus the slabs started to deteriorate with time by breaking down.

Solving the Conflicts

The square was lacking multifunctionality and this was not only a mere aesthetic issue. The designers had to solve the enigma of how to transform the square in a dynamic and static space, a transit zone and contemplation zone. The design should permit the square to be flexible, in order to be the scenario for different types of events; it should not be predictable, as it had to leave a sense of freedom where different types of activities could take over.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

As a design guide, the team created a square grid of 3.5 m by 3.5 m. They placed it over the square; this mesh worked as a skeleton structure that shaped the new square’s design, and it also gave birth to the new pattern for the square’s floor. The paving slabs were replaced by concrete squares that could hold more than 350 Kg/m2, so the matter of the new maximum structural loading was one massive improvement, maybe the most relevant portion of the redesign, because now the square was not tied down to that maximum weight restriction that inhibited the opportunity to have green landscape and different kind of activities.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

Other specific changes had to be done; towards the south we can find the Jardin des cultures. This access was frequently used but was visually blocked and created a feeling of insecurity; the solution here was to insert a new monumental staircase that created visual connections.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

To the north is the Boulevard de l’Hôtel de Ville; this connection has one of the entrances to the sub-level parking lot. This zone was not as pedestrian-welcoming as was wished, it had also visibility issues and for citizens with reduced mobility was not a friendly access point, so here the team took a previously existent pedestrian access and turned it into a ramp so that people on bikes and wheelchairs could also use it. Furthermore, the existing vegetation is reinforced and this seals the engagement of the boulevard with the square.

To the west, we find the Allée Nelson Mandela; here, in particular, many misplaced elements were acting as obstacles towards the fluidity and legibility of the space, such as low walls, banks, etc; also there was no access for people with reduced mobility. The response here was to demolish the misplaced elements and free the space, plus the design of a fusion of a stair and a ramp with vegetation and lighter guardrails. The result turned out very sculptural; this increased the aesthetic value of the zone.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

The Vegetation

We talked before about the square grid of 3.5 m by 3.5 m. Those measurements were also the dimensions of the new micro-gardens; they are easily movable and divisible into 4 parts. On each of the micro-gardens were planted a different kind of trees and flowers. Within the trees we find Scots pines, magnolias that are the evergreen type and maples which are the type that change their color through the seasons.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

The flowers are perennials, wildflowers are ivy, wisteria, poppies, wild chrysanthemums and more; these types of flowers bring color, plant diversity, and micro-fauna such as butterflies and ladybirds. The vegetation has the ability to revitalize a place; these green pixels helped this square to become a true outdoor living space where people pass by and also actually stay. If citizens don’t feel comfortable in a place they will just avoid it and neglect it as much as they can; this, for a public space, is a key factor for its death or life.

Place des Droits de l’Homme. Credit: B+C Architectes

A public space without users is nothing but an urban desert, an easy scenario for not-so-friendly activities. It has been said and written multiple times that multifunctionality is key for the success of public spaces because it helps a space respond to different types of needs that the users and the city may have and allows it to function during any season. This is what was solved through the re-design of this square; the multifunctionality that was missing in the space was brought to the fore, and it revitalized the place, bringing back citizens. Do you think that this so-called multifunctionality has any negative side effects on public spaces?

Recommended Reading:

- Becoming an Urban Planner: A Guide to Careers in Planning and Urban Design by Michael Baye

- Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design With Nature by Douglas Farrs

- eBooks by Landscape Architects Network