Author: Land8: Landscape Architects Network

How “A Changing Neighborhood” is Making a World of Difference

“A Changing Neighborhood”, designed by Espace Libre, Mantes-la-Jolie, France. The urban neighborhood of Val Fourré, located in Mantes-la-Jolie, France, has undergone an amazing transformation, going from bleak to awe-inspiring. The project was completed in 2014 and it covers an area of 56,500 square meters. Escape Libre was the firm responsible for the successful project, commissioned by HLM Interprofessionelle Région Paris. This is the kind of project that demonstrates how much it is possible to change a neighborhood; starting from inspiration and adding talent, one can ensure urban renewal at its finest. Nature is brought back to being the source of everything that is alive and beautiful, blending in with the rest of the urban landscape.

“A Changing Neighborhood”

What Was It Like Before? When the neighborhood of Val Fourré was developed in the 1960s, it was surrounded by nature on all sides. There was the Mantes forest, the Vexin hillsides, and the Seine River, each bringing its own appeal to the urban area. Urban boulevards were created from the conversion of major roads, as the main idea was to link Mantes-la-Jolie with neighboring towns.

Parking spaces were transformed from private to public, thus allowing more space to be obtained. However, in time, the neighborhood degraded and its aspect was desolate, to say the least. Has Val Fourré Been Reborn from its Ashes? Thanks to the talented people working on the project, Val Fourré, like the mythical phoenix, went from bleak to fascinating. The architects working on the project knew how to eliminate all the sadness and the gray, taking advantage of what the neighborhood had to offer. They wanted to make a shift toward nature, making the space a pleasant place to live. And they succeeded, bringing the exceptional landscape back into the center of attention.

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

- How The Fish Market Plaza Revamped This Forgotten Site

- Sjövikstorget Square: Traditional Techniques in Modern Landscape Architecture

- Discover the Ancient Secrets of the Physic Garden

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

“A Changing Neighborhood”: Photo credit: Julien Falsimagne

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

- 1000x Landscape Architecture by Braun Publishing AG (COR)

Article by Alexandra Antipa Return to Homepage

Saving Wildlife Through Building Community led Eco-lodges in Cambodia

Our partners Building Trust International are are aiming to save wildlife with eco-lodges. Building Trust international are pleased to announce a new sustainable design prototype for an eco-lodge that will assist local villagers protecting natural areas by attracting local and foreign tourists to see critically endangered species thereby creating local income that is not based on selling forest products. Building Trust international have worked alongside Atelier COLE, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Sam Veasna Center (SVC) on a new eco-lodge designed and built by the local community, NGO partners and through a hands-on participatory design and build workshop.

Eco-lodges in Cambodia

Lodge designed by Atelier COLE in partnership with WCS and BTi © WCS and Building Trust

Adobe plaster is placed onto bamboo weave. © WCS and Building Trust

The roof is lifted into position. © WCS and Building Trust

The eco-lodge takes shape. © WCS and Building Trust

Community consultation at Tmat Boey. © WCS and Building Trust

- Building Trust International-PLAYscapes Competition

- Building Trust International Interview

- Reflecting on the Past While Looking Forward to the Future with Wildlife Conservation

The workshop itself allowed for the crossover of skills between the Tmat Boey community, local contractors and Building Trust volunteers. Working alongside the community ensured ownership of the project by the people it supports. Building Trust are due to host a number of design and build workshops throughout 2015 promoting natural building, community engagement and sustainable construction techniques.

Community help out on site. © WCS and Building Trust

The Curious Case of Killesberg Park: A Landscape Telling Its Own Story

Killesberg Park by Rainer Schmidt Landschaftsarchitekten GMBH, in Stuttgart, Germany. Every place has its own story. And that story very often is the line framing its authentic character and spirit. In order to reinforce the unique experience each site bears, designers try to “capture” that spirit within their projects. But capturing isn’t enough. It is just the beginning of what is needed for a successful human intervention. To make the most of a place, there are a few necessary and sufficient conditions. They cover the understanding that nature and history should always be treated with respect. In this way only, designers will find the balance between design and function, emotion and conservation. Finding that balance isn’t easy, but it isn’t impossible, either. Landscape architects from Rainer Schmidt Landschaftsarchitekten GMBH found it; let’s see how their project Killesberg Park proves what’s been stated above.

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park

The Story Behind the Landscape The history of Killesberg Park dates back to the time when the area was used as a quarry for industrial purposes. Years of mining at this sandstone quarry caused severe damage to the landscape’s topography. And although the place had a prime location, the land was unsuitable for buildings on account of its former use. Since the 1920s, the goal of planning the area has been focused on connecting the separate parks and gardens of Killesberg. An early sign of its current use came in 1939, when the city of Stuttgart applied to host the Reichsgartenschau (National Garden Show). This is when the idea to redevelop the area and make it an accessible green space for residents emerged.

Killesberg Park. Credit: ARGE Zukunft Killesberg

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

- Beautiful Plaza Celebrates Canadian Landscape

- Perez Art Museum Embraces the Landscape Inside and Out

- Ceramic Museum and Mosaic Garden

Forward-looking Design Within all these new sensations and underlying themes honoring the social and environmental past lies the ultimate idea of creating a future-oriented design. The idea is implemented by different environmentally conscious methods used in the construction of the ecosystem in the area. The main sustainable and ecological approaches used in the project are two: • The rain water management is successful due to the underground cistern, which collects water from roofs and pipes it to the park’s lake. After that, water returns to its natural circulation; • The park’s green “pillows” form various biotopes for flora and fauna by their individual microclimatic conditions. The meadow grasses require mowing only twice a year, which reduces significantly the money and time spent on their maintenance.

Killesberg Park. Photo credit: Raffaella Sirtoli

- 100 Landmarks of the World: A Journey to the Most Fascinating Landmarks Around the Globe by Parragon Books

- Public Art: Theory, Practice and Populism by Cher Krause Knight

Stirring Emotions at the Netherlands Army Museum and Netherlands Air Force Museum

Netherlands Army Museum and Netherlands Air Force Museum Landscape Design, by H+N+S Landscape Architects in the Former Airbase Soesterberg, the Netherlands. War is a painful, devastating, and dynamic situation. Maintaining the memory of such events is hard, yet necessary in order to protect the next generations from repeating the mistakes of the past. This should be the purpose of a war museum nowadays. The landscape design for the Netherlands Army Museum and the Netherlands Air Force Museum sheds a new light on the concept of memory and provides a new perception regarding our notions of war, history, and the armed forces.

Inspection by a senior military of the monument in its new context of the new memorial garden. Photo courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

Netherlands Army Museum and Netherlands Air Force Museum

The complex that houses both museums is located in the facilities of a former military airbase called Soesterberg. The location bears traces of World War II history and NATO use, and also maintains important natural qualities. What is truly fascinating about this project is that what once used to be part of the military facilities has been restored into a natural reservoir. It appears as if nature has taken its toll over human action. The museum complex seen from above seems to have been invaded by the adjacent forest and heath. This coexistence forms a dynamic relationship between the building and its surroundings, which gives more emphasis to the museums’ character.

The fog fen in front of the National Military Museum in Soesterberg, The Netherlands, that opened its doors on December 11. The museum park of 45 hectare is designed by Dutch firm H+N+S Landscape Architects. It surrounds the museum with nature and air force heritage and is visible in each direction as a backdrop to the museum collection.

- Forming the museums’ surroundings as well as interesting vistas toward the landscape from the building’s interior, also serving to complement the museums’ exhibitions.

- Creating access to the museum complex.

- Preserving and restoring the important traces of the military base.

- Allocating a monument, a memorial garden, and a 3,000-person arena.

- Restoring the 45-hectare area and creating a sustainable sylvan ecosystem.

The museum complex is divided into three terraces. Each terrace has a special function. The top of the hill is a natural landmark surrounded by a heath valley. On the middle terrace — where the visitor arrives — the history of the area is displayed. The museum complex itself has been situated near the runways. The arena is on the lowest level, and there is a memorial area with garden and plaza on the east side.

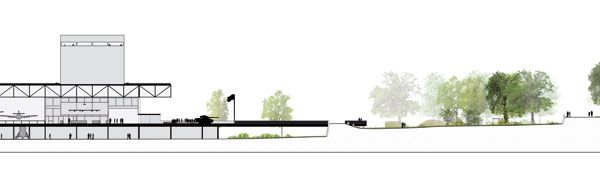

A Section of the museum entry, with the entry bridge above the fern garden, connecting the museum to the gabion wall that marks the mid-level terrace with several hidden bunkers. Image courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

- Beautiful Plaza Celebrates Canadian Landscape

- Perez Art Museum Embraces the Landscape Inside and Out

- Ceramic Museum and Mosaic Garden

View from the Belvedere over the heath valley, with raised path along fens, towards the museum. Photo courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

Memorial garden in its first season. The monument is surrounded by a large round taxus hedge, embracing a space with borders in color palettes. They tell a story that leads from war –red-, via emotions –purple-, reflection –blue-, towards peace –white-. Photo courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

Construction of gabion stronghold, creating the entry path towards the arena.Photo courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

View towards the entry bridge, leading over the fern garden. Photo courtesy of H+N+S Landscape Architects

Netherlands Army Museum and Netherlands Air Force Museum

This project has managed to reveal beauty where beauty was hard to find. It has not evaded the context and the history of the place, nor did it turn away from the negative tension that the memory of war bears. The Netherlands Army Museum and the Netherlands Air Force Museum Landscape Design has taken context, history, nature, and landscape narrative a step further. Recommended Reading:

- 100 Landmarks of the World: A Journey to the Most Fascinating Landmarks Around the Globe by Parragon Books

- Public Art: Theory, Practice and Populism by Cher Krause Knight

Article by Eleni Tsirintani Return to Homepage

Atlantic Park Combines Ecology and Community to Create a Spectacular Urban Space

Atlantic Park by Battle I Roig Arquitectes, Santander, Spain. Atlantic Park is a recently constructed urban park in the city of Santander, on Spain’s northern coast. The design, by Batlle I Roig, combines elements of ecological restoration and urban community parks. Batlle I Roig Arquitectes is a multidisciplinary architecture, planning, and landscape design firm based in Barcelona, Spain. The firm’s portfolio boasts a huge variety of projects, ranging from large-scale environmental restorations to the design of schools and social housing.

Atlantic Park

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

- Exceptional Ecological Park Reconnects Children With Nature

- 5 Great Ecological Powerhouses of Landscape Architecture

- Giant Sized Pergola Creates Ecological Haven

An artificial lake was also created as part of the design. The lake acts as a reservoir for runoff, an expansion of the marshy habitat, and as a visual focal point in the park.

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Atlantic Park. Photo credit: Jorge Póo

Balancing Community with Ecology through Atlantic Park

Batlle I Roig’s design for Atlantic Park aims to transform an unused and unloved dumping ground into a vibrant public space that serves the community’s needs while still protecting the area’s unique ecology. The new design has significantly opened up access to the Vaguada de las Llamas riverbed, letting locals access what was closed off for decades and putting a stop to much of the illegal dumping that had degraded the site for years. The project is a reminder that human and ecological use don’t necessarily have to be at odds with one another. As designers, finding creative ways to balance our responsibility to the environment with community needs is key to creating successful and sustainable urban spaces. Awards: Finalist for the FAD 2007 Awards Recommended Reading:

- Basics Landscape Architecture 02: Ecological Design by Nancy Rottle

- Principles of Ecological Landscape Design by Travis Beck

Article by Michelle Biggs Return to Homepage

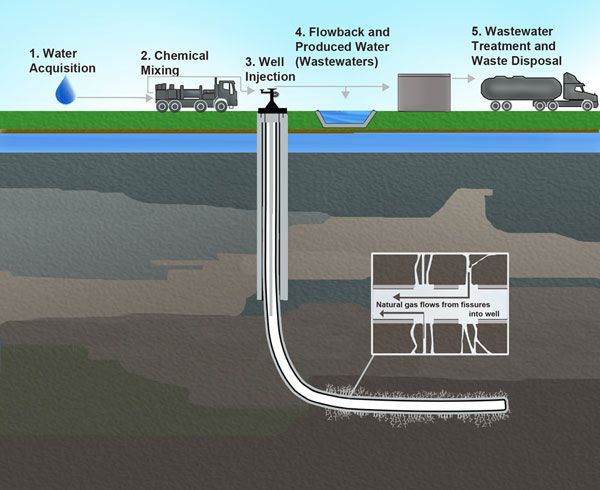

Fracking: All You Need To Know

We take a closer look at the highly controversial topic of fracking. This is a great chance to delve into a truly hot topic that leaves nobody indifferent. You have probably heard about the controversial energy technique known as “fracking”, which is being used more and more often around the world. What exactly is fracking? Hydraulic fracturing allows us to access shale gas, which is mainly methane locked in a deeper rock stage beneath the Earth’s surface. The process consists of drilling vertical wells that turn horizontal underground, opening tiny fractures in deep rocks into which high-pressure chemical fluids are injected. The gas then escapes through the fractures and is collected to be used as an energy source.

Fracking

WATCH ME: Fracking explained: opportunity or danger

Here we have prepared a list of carefully chosen points about the fracking phenomenon. What do the numbers tell us about water safety? According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, one fracture could require the use of 2 million to 5 million gallons of fresh water from the nearby area. During the process, more than 315 tons of toxic chemicals are mixed with the water to form the fracking fluids. In the end, waste fluid is supposed to be removed to open pits or tanks, but the EPA says 20 percent to 85 percent remains underground, resulting in the possible contamination of drinking water sources.

Illustration of hydraulic fracturing and related activities. Image credit: Source. Author US Environmental Protection Agency. Licensed under the Public Domain

See more energy related articles:

- Pavegen: Using the Pavement to Generate Energy

- Will These Solar Roadways Change The World?

- The Secrets Behind the Smart Highway

The background of the fracking boom The technique as we currently know it is only 16 years old. It was developed in Barnett, Texas after Mitchell Energy spent almost 20 years improving the process of accessing shale gas. The company first applied hydraulic fracturing technology successfully in 1999, but it took three more years for general industry to look at fracking as a large-scale and advantageous method of extracting the gas. The sustainable footprint According to the U.S. Energy Information Association, the United States could be energy self-sufficient by 2035 because of its shale gas reserves, which are supposed to reduce dioxide carbon emissions to the atmosphere. However, because fracking activity produces methane leaks, being 25 times more toxic than carbon dioxide, and coal production would be available to export, the sustainability factor may be misleading. How fracking transforms landscapes On average, each well translates to ground consumption and heavy truck traffic. The associated facilities redraw undeveloped natural habitats into fragmented industrial scenery, like this one in Wyoming. Those cleared lands also have knocked on the door of protected public fields, such as Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota and other high-value places for wildlife and nature conservation. WATCH ME: A Boom With No Boundaries: How Drilling Threatens Theodore Roosevelt National Park

World map of shale gas As this EIA report reveals, China, Argentina, and Algeria lead the shale gas geography in terms of recoverable reserves. However, they do not have suitable infrastructure and technology to take advantage of the potential yet, so the United States jumps into the first position at the moment, attracting special attention to the Marcellus Shale formation.

Could fracking become greener?

Innovative alternatives are needed, and one of them proposes using biodegradable polymers in fracking fluids to prevent residues from remaining underground. The University of British Columbia also is studying an interesting method to reuse wastewater and produce salts for the fracking process out of carbon dioxide. Most unexplored reserves of shale gas are under our feet. But it is important to keep our eyes up to look at the most unexplored effects of fracking on our landscapes. Recommended Reading:

- The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World by Russell Gold

- Snake Oil: How Fracking’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future by Richard Heinberg

Article by Elisa Garcia. Return to Homepage Featured image: Print screen from Youtube video: Fracking explained: opportunity or danger

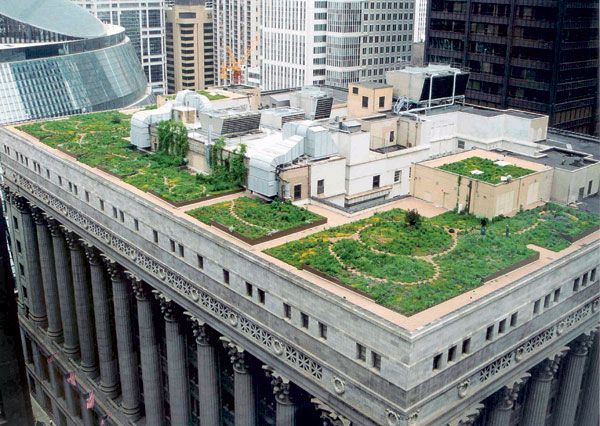

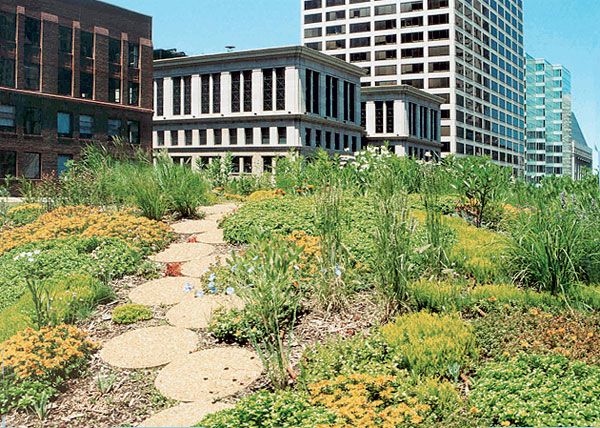

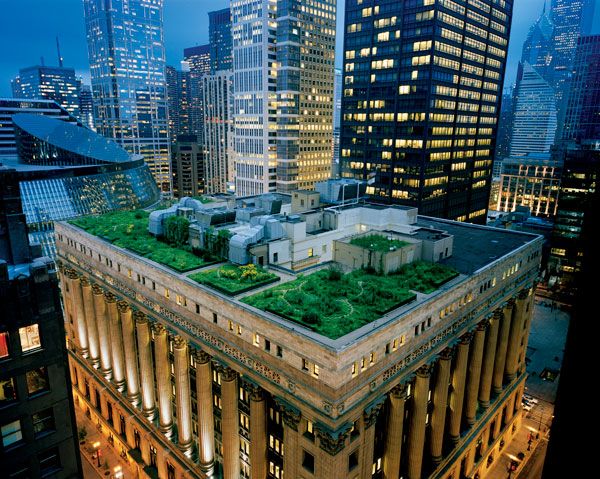

How The Chicago City Hall Green Roof is Greening the Concrete Jungle

Chicago City Hall Green Roof by Atelier Dreiseitl and Conservation Design Forum. The typical image we all have of a city is of towering high-rise blocks, densely packed tarred streets and a generally hard urban environment. Nature is isolated in manicured green parks or in linear rows of gray-looking trees. The city is perhaps the furthest thing from a natural environment and the closest thing to an urban desert. But what if we begin to green this concrete jungle? Projects such as the High Line in New York have shown this can be done, and the wave of vertical green walls has created a new ecological fashion statement. There is, however, one method that trumps all of this in terms of long-term benefits: green roofs.

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Mark Farina

Chicago City Hall Green Roof

Urban Heat Island Effect The city of Chicago was forced to consider this option after a heat wave in 1995 claimed a number of lives due to extreme inner city temperatures. These extreme temperatures were caused by the “Urban Heat Island effect”, in which heat in the city is absorbed by pavements, buildings, and asphalt. Stormwater in Chicago is also a major problem because the city’s stormwater and sewage systems are combined. This means that during a downpour, the system is overwhelmed, resulting in overflows and sewage pollution.

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Conservation Design Forum

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Conservation Design Forum

- Why Should You Have a Grass Roof?

- A Roof Garden That’s so Good, You Might Want to Work There!

- WARNING: Why You’re Losing Money By Not Using a Green Roof

Trees are usually not included in roof gardens due to their extreme weight and depth requirements, but the intensive design accommodated two trees that were planted on cantilevered platforms over structural columns. In total, 20 000 plants of more than 150 indigenous species were planted in the 1,885-square-meter roof garden.

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Mark Farina

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Cook and Jenshel NG Creative

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Conservation Design Forum

Chicago Green Roof. Photo credit: Conservation Design Forum

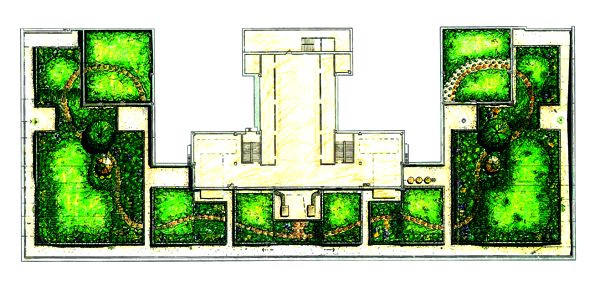

Chicago Green Roof Masterplan. Credit: Dreiseitl

Chicago City Hall Green Roof

Additional project credits: Recognition: ASLA Merit Award for Design 2002; IL-ASLA Honor Award for Design 2002; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) National Earth Hour City Challenge 2014 Project Team: Weston Solutions – Project Lead, Project Management. McDonough + Partners – Architect. Atelier Dreiseitl – Green Roof Engineering. Bennett and Brosseau – Roofing Contractor. RoofMeadow (formerly Roofscapes) – Green Roof System. Intrinsic Landscape – Planting Installation. Greencorps Chicago– Long-term Landscape Maintenance Recommended Reading:

- The Green Roof Manual: A Professional Guide to Design, Installation, and Maintenance by Linda McIntyre

- Green Roof Construction and Maintenance (GreenSource Books) (McGraw-Hill’s Greensource) by Kelly Luckett

Article by Rosemary Buchanan. Return to Homepage

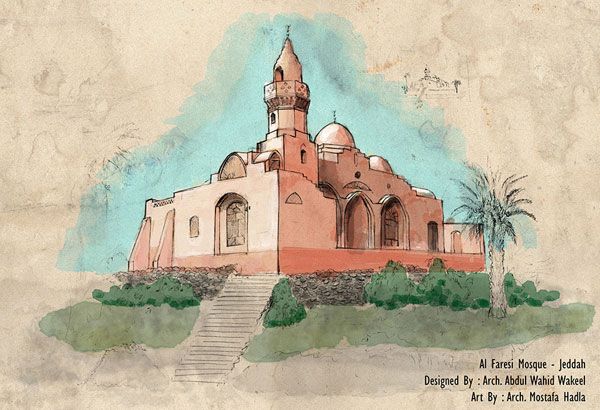

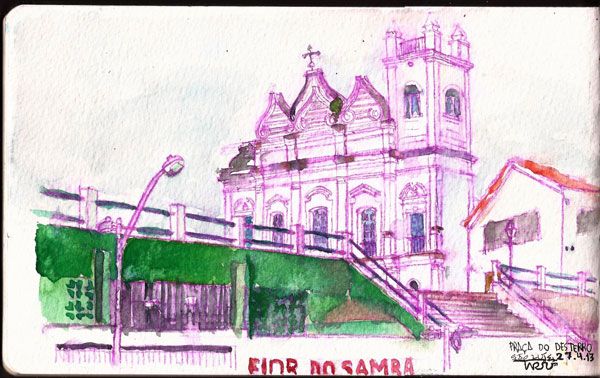

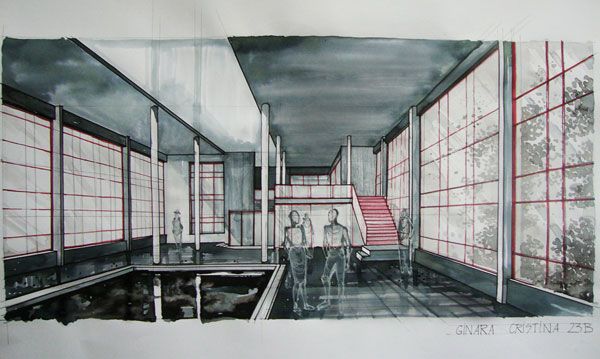

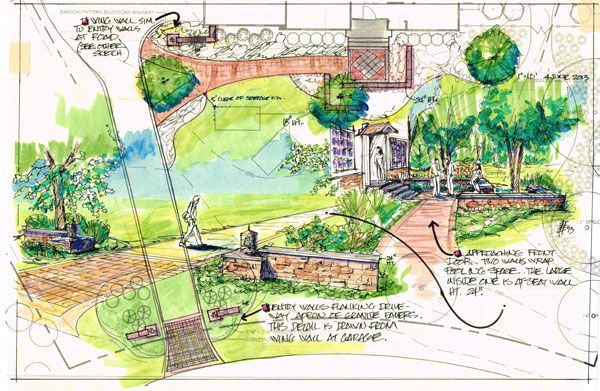

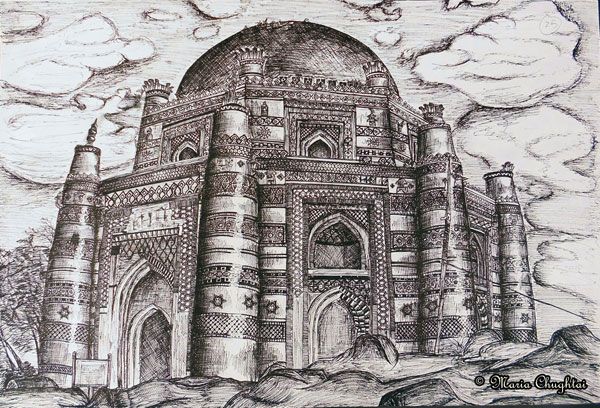

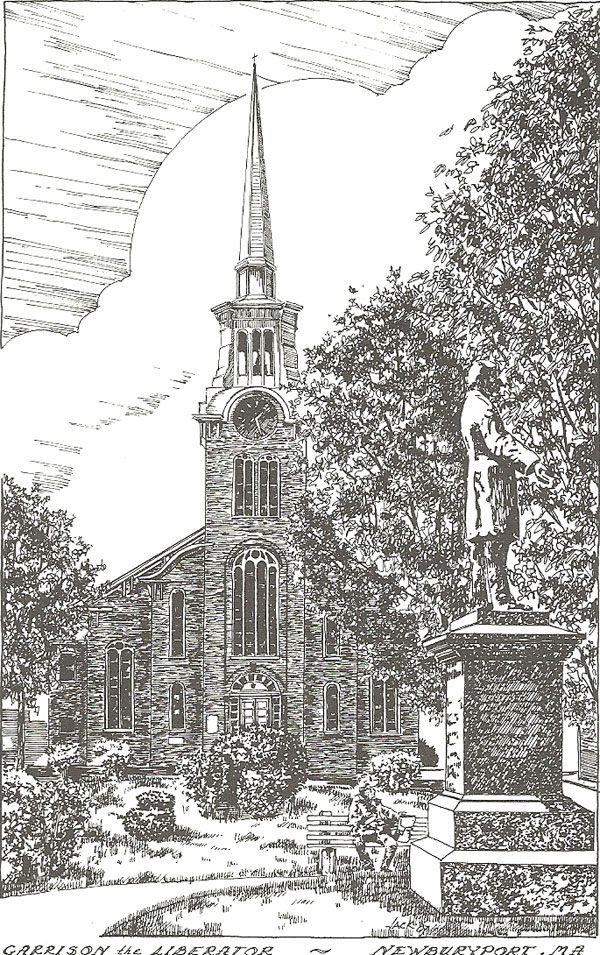

Sketchy Saturday |034

This week’s Sketchy Saturday top 10. Here we go with 10 enthusiastic, talented Sketch-Stars that have submitted their handy work to the office for this week’s Sketchy Saturday. In this week’s top 10 we see a range of styles, and levels of creativity which show that risk-taking is involved in getting your message across. Each sketch is as unique as a fingerprint and is almost like the artist’s signature. This is work that not only embodies their skills and creativity, but their experience, passion and thought process. To appreciate a creative piece of work is to open a doorway to understanding the person who created it. A gift that inspires us and connects us to one another. Enjoy this week’s Sketchy Saturday top 10! 10. by Anastasia B. Uli, Master of Sustainable Design UF student, Gainesville FL

Anastasia Uli

Mustafa Hadla

Tarsis Aires

Oana Chiriac

Isa Eren AKBIYIK

Ginara Cristina

Peter Bonette

- Freehand Drawing & Discovery by James Richards

- Drawing for Landscape Architecture by Edward Hutchison

- Digital Drawing for Landscape Architecture, second edition

3. by Marika Cieciura, landscape architecture student at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK, on the exchange program at South Dakota State University

Marika Cieciura

Maria Chughtai

Jack Tremblay

- Sketching from the Imagination: An Insight into Creative Drawing by 3DTotal

- Architectural Drawing Course by Mo Zell

Article by Scott D. Renwick Return to Homepage

Borås Textile Fashion Center Mark the Beginning of a new Phase in the Textiles Industry

Borås Textile Fashion Center, Simonsland, Skaraborgsvägen, Borås, Sweden by Thorbjorn Andersson with Sweco Architects.

This remodeled factory building from the 1870s — now the new headquarters for textiles history, research, and higher education — weaves notions from Sweden’s rich textiles tradition into details both large and small. Landscape architect Thorbjorn Andersson with Sweco Architects worked alongside a team of consultants to create the Boras Textile Fashion Center, which opened in September 2013. The Fashion Center merges many major institutions in Sweden’s textiles industry to form a destination, center of activity, and natural meeting place. This mecca of knowledge and business also houses the University of Textile and Fashion, offering a world-class location and facility in which students can learn, research and practice.

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center

The center is designed to pay homage to the long history of the textiles industry in Sweden. In the front entrance of the university, the floor is laid out as a carpet of stone. Designers used three different colors and types of granite to resemble a weaving pattern developed by Joseph-Marie Jacquard in 1805.

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Sketch courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

- How The Fish Market Plaza Revamped This Forgotten Site

- Sjövikstorget Square: Traditional Techniques in Modern Landscape Architecture

- Discover the Ancient Secrets of the Physic Garden

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

Borås Textile Fashion Center Presents a New Era for the Textile Industry

The Fashion Center is a hub in the center of Boras, Sweden. With accessible transportation connections including rail, air, ports, and highways, this is an ideal location for the development of new and innovative textiles practices. The museum and overall design of the Fashion Center mark the beginning of a new phase in the textiles industry while paying respect to its history. The center even incorporates cafes, restaurants, cultural attractions, shopping, and recreation to attract visitors and guests from near and far. Additional project credits: Team: PeGe Hillinge, Staffan Sundström, Ronny Brox, Per Johansson (lighting design). Consultants: DTH arkitekter (Dominic Wansbury) together with Sweco architects (Peter Jansson), Stiba (construction). Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Rachel Kruse Return to Homepage

How Place d’Youville is Teaching us That Artificial is Not Fake!

Place d’Youville in Montreal, Quebec, Canada design by Claude Cormier + Associés. What is landscape architecture, really? Perhaps one of the most difficult and frustrating parts of the landscape architecture profession is the fact that very few people understand what it is that we really do. No, we are not landscapers or gardeners, and while we do also work in small gardens, our scope and understanding is far greater. Landscape architecture is the understanding of the complex nature of a site: the dynamic relationship between the natural and the built environment and the overlaying of the cultural context. “artificial, not fake” Canadian landscape architect Claude Cormier has begun to challenge this notion by embracing the constructed landscape and celebrating the artificial. His philosophy of “artificial, not fake” falls under the “conceptualist” movement, prioritizing the concept or big idea as the driving force behind a project.

Sugar Beach at night by Claude Cormier + Associés. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Birds eye view of Sugar Beach with mounds. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Place d’Youville

Cormier (in collaboration with Groupe Cardinal Hardy) has adopted this approach in his recent project, Place d’Youville in Montreal, Quebec. Place d’Youville is a historical square in Montreal and forms the meeting point of important roads at the gateway to the city’s waterfront and old port.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Although Cormier’s background is in plant breeding, he has directly admitted to preferring to work with inanimate elements due to impatience with the process of habitat growth and creation.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

Awards for Place d’Youville

Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, Regional Honor – Place D’Youville, Old Montreal, Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, National Merit – Place D’Youville, Old Montreal. Recommended Reading:

- Site Engineering for Landscape Architects by Steven Strom

- The Artful Garden: Creative Inspiration for Landscape Design by James van Sweden

Article by Rose Buchanan. Return to Homepage

Strijp-s Reveals the Key to Brilliance: Keep the Old Factory Charm

Strijp-S, by Piet Oudolf, Carve, Deltavormgroep and Har Hollands, Eindhoven, Netherlands. Eindhoven, for those who’ve never been there, may seem to be just a tranquil, sleepy town somewhere in the Netherlands. But in fact it is home to many unconventional landscape architecture projects, including the tulip chairs and the fabulous glowing bike path “Starry Night” that one of my inspiring colleagues wrote about. Also among these projects is Strijp-S, which has helped to turn the city’s image upside down: from a boring factory village to a modern design metropolis. The collaboration behind this fantastic project in southern Holland comes from the design and engineering office of Carve, landscape architect Piet Oudolf, Har Hollands (lighting design) and Deltavormgroep (designers of public space underneath the pipe street). Together, they have reinvigorated a once “forbidden city” of industrial production into a modern apartment site while respecting the area’s original factory character.

Strijp S. during the summer. Photo credit: Carve (Marleen Beek)

Strijp-S: Every Light Has its Shadow

What is left behind when a huge factory site is closed down? When Phillips pulled its last European factory from Eindhoven, it left behind 27 hectares of abandoned industrial complexes and a dark place that once used to be filled with the bright incandescence of new light bulbs. The move forced Eindhoven to evolve and become a grown up city that creates an alternatively bright future for its residents. Related Articles:

- Community Turn Abandoned Industrial Site into Public Park

- Industrial Site Transforms into Beautiful Landscape

- MFO Park in Switzerland

When Different Layers Form a Whole Even under the difficult circumstances that every former factory site carries, the outcome of the Strijp-S project is phenomenal. The clever mix of the old factory charm with new layers of plants, light-blue steel construction, and a brilliant lighting design by Har Hollands is an outstanding and harmonious collaboration that only few designers manage to achieve.

Strijp S. during the summer. Photo credit: Carve (Marleen Beek)

Strijp S. during the summer. Photo credit: Carve (Marleen Beek)

Strijp S. during the Autumn. Photo credit: Carve (Jasper van der Schaaf)

Strijp S. during the Autumn. Photo credit: Carve (Jasper van der Schaaf)

Strijp S. during the Autumn. Photo credit: Carve (Jasper van der Schaaf)

Strijp S. during the Autumn. Photo credit: Carve (Jasper van der Schaaf)

- Planting: A New Perspective by Noel Kingsbury

- Hummelo: A Journey Through a Plantsman’s Life by Piet Oudolf

Article by Sophie Thiel Return to Homepage

Urban Freeway Removal: Addressing a Failed Experiment with Landscape Architecture

Urban Freeway Removal is seen by many as the next logical step following a failed experiment in urban planning. The construction of urban freeways in cities was an untested idea when it was developed around the world in the late 1950s. In the past 50 years, tens of thousands of miles of highways have been built around the globe. However, there is strong evidence that urban highways are a failed experiment! This has led many cities to question the placement of freeways and whether they merit further investment or whether urban freeway removal should be considered. What can be done when a highway no longer makes sense?

Urban Freeway Removal_After Aerial Photo of Greenway_Rose Fitzgerald Kenedy Greenway by Hellogreenway CC2.0

Urban Freeway Removal: A Brief History

Unintentional Side Effects and the Original Intention of Urban Freeways Governors and supporters typically sought urban freeways as a solution to congestion, but years of real-world case studies and numerous empirical studies have shown us today that new road capacity usually increases traffic in direct proportion to the amount of new road space. Moreover, the adverse impacts of urban freeways on their surroundings — such as displaced communities, decreased road safety, environmental degradation, land-use impacts and threats to residents’ health through air pollution and increased accidents — were not considered while force-fitting limited-access freeways into cities.

Urban Freeway Removal_TomMcCallWaterfrontParkatnight by Cacophony CC2.0

- The ChonGae Canal Turns an Auto-Centric Zone into a Pedestrian Haven

- 280 Million Euros Invested into Urban Revitalisation Project – Rio Madrid by West8

- Ground Breaking Masterplan Redefines The City of Bogotá

How Urban Freeway Removal Stimulates Liveable Neighborhoods

The initial hype of building freeways was soon followed by a movement of taking down those unpleasant thoroughfares. However, the urban freeway removal itself does not represent the final solution.

Rio Madrid by West 8. © Municipality Madrid

Urban Freeway Removal_The ChonGae Canal. Photo credit Taeoh Kim

- Increased land values,

- a decrease in motor vehicle use; and

- less air and noise pollution in the region.

Furthermore, the redevelopment of the waterfront area has also helped by reducing crime rates, creating safer and more pleasant spaces for pedestrians, and considerably improving the quality of life in downtown Portland.

Urban Freeway Removal_Waterfront Park Portland by brx0 CC2.0

- The reduction in traffic accident fatalities,

- the decline of travel times along the corridor,

- the reduction of air pollution; and

- the decrease of aggregated crimes.

Freeways are a tool to move traffic long distances at high speed. Without a doubt, cities often need urban freeways, but if they are misplaced, residents, businesses, property owners, and neighborhoods along the freeway suffer. Health and quality of life can be important factors for cities in deciding whether or not a new freeway should be built and whether already existing freeways need to be torn down.

Urban Freeway Removal_SeattleI5Skyline by Cacophony CC2.0

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Sophie Thiel Return to Homepage